Greek Revival Parlor

New York, New York, ca. 1835

Amelia Peck, Marica F. Vilcek Curator of American Decorative Arts; and Moira Gallagher, Research Associate

The Robert and Gloria Manney Greek Revival Parlor, on view in Gallery 738, is a re-creation of what the parlor of a fashionable New York City townhouse of about 1835 might have looked like. The room was designed to showcase a rare suite of seating furniture made for New York lawyer Samuel A. Foot (1790–1878) by the firm of cabinetmaker Duncan Phyfe (1770–1854). The only 1830s period architectural elements are the Ionic columnar screen with mahogany sliding doors at the room's entrance and the black marble fireplace. The rest of the room was created in 1983 based on designs found in popular architectural pattern books written about 150 years earlier, as well as interior elements copied from extant New York City town houses built in the first decades of the nineteenth century.

An alternate view of the Greek Revival Parlor.

The Greek Revival Style in America

Greek Revival buildings, designed in America's first truly national architectural style, sprang up in the decades between 1820 and 1850. Although Neoclassicism had been popular since the end of the eighteenth-century, the lighter designs of the Federal period were derived primarily from Roman models that had been filtered through the creative minds of English designers such as the Adams brothers. (For examples of this type of interior, see the Baltimore Room and the Benkard Room.) The bolder, more robust Greek Revival, however, put a far higher premium on archaeological correctness. Architects studied actual Greek ruins, if not in person then through books, the most illuminating being Stuart and Revett's multi-volume tome, The Antiquities of Athens (Vol. 1, 1762), which was profusely illustrated with accurate measured drawings.

The Greek Revival style expressed many things about American ideals. During the 1820s the Greeks were battling the Ottoman Empire for independence, and Americans, like the citizens of many European countries, were strongly supportive of the Greeks' struggle. But, first and foremost, the Greek Revival style represented American optimism before the Civil War, at a time when the country's democratic system, adapted from the ancient Greek model, seemed to be flourishing. People who built houses, churches, and civic buildings based on Greek temple forms expressed their belief that America was becoming a great civilization, one that would rival the glories of the ancient past.

Image: Designed by William Strickland (American, 1788–1854), Second Bank of United States, 1818–24, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Copyright 2006 Peter Clericuzio. Strickland's temple-like structure, inspired by the Parthenon in Athens, Greece, is among the earliest Greek Revival buildings in the United States

The New York City Townhouse

Greek Revival townhouses along Washington Square North, New York, New York. Beyond My Ken, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In rapidly growing New York City, Greek Revival townhouses filled block after block in the area between Greenwich Village and Thirty-fourth Street. Designed for the expanding middle class, these structures were usually built on lots twenty to twenty-five feet wide and one hundred feet deep. A typical house might be three full stories high, above a raised basement, and often topped with a garret. It was usually only two rooms deep, with a stair hall to one side. The raised basement held the kitchen and perhaps the servants' dining room; the main, or first floor contained the public rooms, while the second and third floors had the family bedrooms, and the garret held the servants' bedrooms. The main floor always had front and back parlors, which were invariably separated by a columnar screen, often with sliding doors, like those at the entrance to in this room. The front parlor was saved for formal entertaining, while the back parlor was often a family sitting room that also served as a dining room.

Alexander Jackson Davis (American, 1803–1892). Greek Revival Double Parlor, ca. 1830. Watercolor, black ink and wash, and gouache with scratching out over graphite on paper laid on canvas. New-York Historical Society.

Envisioning an Ideal Greek Revival Parlor

The Foot suite on display in The Met's exhibition 19th-Century America, April 16–September 7, 1970. The suite was exhibited in a period-room-like setting.

The Museum's Greek Revival Parlor is not actually a period room. It was not removed from a house, unlike most of the other rooms in the American Wing. It is period-style gallery, meant for the display of furniture from the 1830s. In 1966, the Museum received the gift of a suite of furniture made in about 1837 for lawyer Samuel Foot by the workshop of Duncan Phyfe. When it arrived at the Museum, there was no room or gallery to display this elegant group. In 1970 the suite was shown together for the first time in The Met's exhibition 19th-Century America, which celebrated the decorative and fine arts from 1800 to 1900. The exhibition's design included temporary room vignettes, including a setting for the Foot suite.

When the expanded and remodeled American Wing opened to the public in 1980, it contained space for new period rooms that would showcase the quickly changing styles of the nineteenth century. Along with the other Revival styles of the era, such as Rococo Revival, Gothic Revival, and Renaissance Revival, it was decided to represent the Greek Revival style. Unlike the other revival-style period rooms, which incorporated architectural elements removed from nineteenth-century houses, the Museum decided to create a parlor in the Greek Revival style by reproducing architectural elements found in pattern books and architectural treatises popular during the 1830s and 1840s.

Creating a Room

Left: Detail of Plate 60 in Minard Lafever's The Modern Builder's Guide (1833). Right: Columnar screen from a New York Townhouse. American, ca. 1830. Wood, 168 x 179 in. (426.7 x 454.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of C. G. Jung Foundation for Analytical Psychology, Inc., 1974 (Inst.1974.2.1)

In 1965, the Museum received a set of double parlors from the Whittemore house in Astoria, Queens, New York. Built around 1850, the house was designed in a transitional Classical Revival style with elements that could be considered late Greek Revival, such as the Corinthian style columnar screen. One of the parlors was earmarked to show the furniture of John Henry Belter (1804–1863), a master of the Rococo Revival style (see The Rococo Revival Parlor), and curators thought about using the second parlor to display the Greek Revival Phyfe suite. But after much thought, it was decided that this plan was not ideal.

There was another, earlier columnar screen in the Wing's collection, with Ionic columns and a pair of glossy mahogany pocket doors. This high-style architectural room divider is based almost exactly on Plate 60 of Minard Lafever's The Modern Builder's Guide (1833). Lafever was one of the most popular architectural pattern book writers in America during the mid-nineteenth century (for more on Lafever, see below). While the curators had no doubt that the screen was made in New York soon after the publication of that book, the townhouse it was originally made for remains a mystery. When it was donated to the Museum in 1974, it had been removed from a townhouse on Thirty-Ninth Street that was not built until 1869. It may have been moved there from another location, perhaps in the early twentieth century when Classical design once again became fashionable for a time. It was decided to build a room for the Foot parlor suite around the impressive screen. Except for the black marble fireplace mantel in the room, which dates to about 1825 and came from a house owned by the Halsted family in Rye, New York, all of the other architectural elements of the room were constructed in the early 1980s, inspired for the most part by Lafever's books.

Informed Choices from Period Pattern Books

Minard Lafever's books were some of the most popular American architectural pattern books published in the first half of the nineteenth century. His The Modern Builder's Guide was reprinted six times, the last edition in 1855, and The Beauties of Modern Architecture (1835) had four reprintings, again ending with an 1855 edition. Published in New York City, the books had an especially strong influence there. Simply worded and illustrated with clear diagrams and plates, they were meant for the "operative workman" (house builder) rather than an architect or scholar. Oswaldo Rodriguez Roque (1949–1989), the curator in charge of designing and installing the Greek Revival Parlor, though perhaps a more scholarly reader than Lafever intended, found his books to be an invaluable resource.

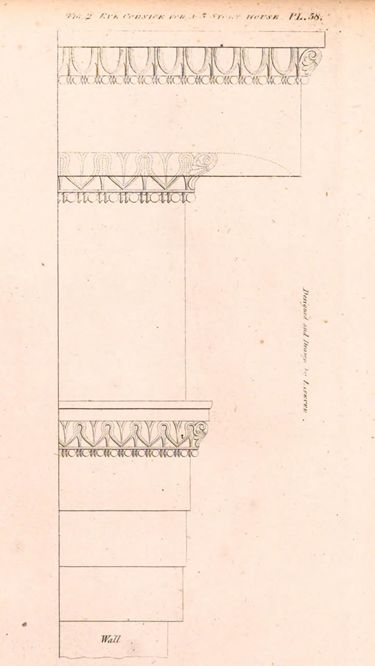

Image: Detail of Plate 58 from Minard Lafever's The Modern Builder's Guide (1833)

The room was proportioned as Lafever advised: the deep plaster cornice was copied directly from Plate 58 of The Modern Builder's Guide, which shows a "Stucco Cornice For Story 12 Ft. to 14." Only the main floor in a typical townhouse would have had a ceiling as high as twelve to fourteen feet, so Lafever's drawing is undoubtedly meant for a parlor. The central molded plaster ceiling rosette was copied from The Beauties of Modern Architecture, where it appears in Plate 21 as "Design for a Centre Flower" and is described as "appropriate to parlors of the first class." The door surrounds were copied from an intact Greek Revival parlor in a house on East Eleventh Street in New York City. However, the ornately scrolling top portions of those original period surrounds can be traced to Plate 19 in The Beauties of Modern Architecture and the side panels to Plate 80 in The Modern Builder's Guide.

Image: Detail of Plate 21 from Minard Lafever's The Beauties of Modern Architecture (1835)

Decorating the Room: Walls, Carpet, and Curtains

The Aymar family had red and gold drapes and carpeting in the stylish Greek Revival parlor of their New York City townhouse. Attributed to George W. Twibill Jr. (1806–1836). The Family of John Q. Aymar, ca. 1833. Oil on canvas, 34 3/4 x 42 in. (88.3 x 106.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of A. Grima Johnson, 2008 (2008.573).

As was popular in the day, the smooth plastered walls are painted a warm beige. Paint analysis was conducted on extant New York interiors of the time, such as Colonnade Row (1832) on Layfayette Street, which helped the curators decide on an appropriate period color. A modern reproduction of a wall-to-wall Brussels (looped pile) carpet was laid on the floor. Its design was accurately woven from an 1827 watercolor point paper pattern found in the archives of an English carpet mill. The original colors specified for the five-color wool carpet were blue, white, light drab, black, and dark drab, but the written instructions on the point paper for several other colorway possibilities inspired the curators to weave it in a classic red and gold combination to match the coverings on the furniture.

Sam Dornsife working on the hearth rug, 1983. American Wing curatorial files.

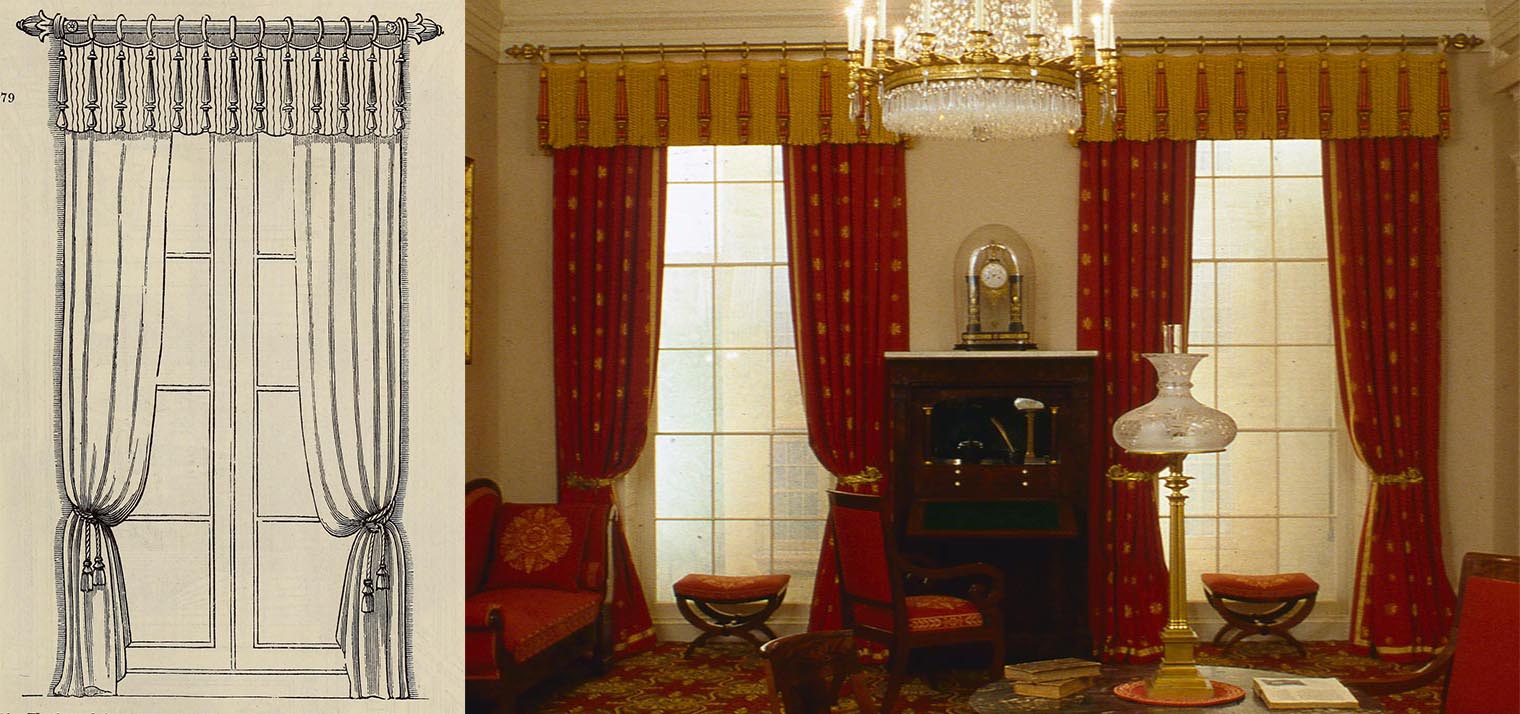

The hearth rug was designed to complement the carpet design, and hand-needlepointed by Samuel J. Dornsife (1916–1999), a pioneer in the authentic restoration and re-creation of nineteenth-century interiors for museums and historic houses who consulted on the room. The silk brocade curtains, with their unusual large bullion-fringe valance, were copied from Plate 1979 of J. C. Loudon's Encyclopedia of Cottage, Farm, and Villa Architecture (London, 1833).

Left: Detail of Plate 1979 from J. C. Loudon's Encyclopedia of Cottage, Farm, and Villa Architecture (1833). Loudon's Encyclopedia, with its myriad designs for house building, decoration, and furnishing, was much consulted on both sides of the Atlantic. Right: Window draperies in the Greek Revival Parlor.

Decorating the Room: Upholstery

Interior view of the parlor at Hillcrest, the Summit, New Jersey, home of Worthington and Euphemia Foot Whittredge. Photograph, ca. 1900. Note the couch on the right with woven designs in the seat and back fabric. American Wing curatorial files.

For the special exhibition 19th-Century America (1970), the seating furniture was upholstered in reproduction fabric that was meant to emulate the suite's original coverings. When the parlor suite came to the Museum in 1966, it no longer had its original upholstery, but photographs of it were available, both from the donor's family and published in an 1939 book by decorator Nancy McClelland called Duncan Phyfe and the English Regency. In that book, it was noted that the furniture had "its original covering of crimson mohair with white woven designs."

An early nineteenth-century European sofa, not associated with the Foot family, was identified in the collection of the Cooper Hewitt Museum. Miraculously, it still had its original covering, with seat medallions and trim that were an exact match to parts of the design of the Foot suite upholstery observed in the old photographs. The sofa's covering was also red, with designs in orange and gold rather than white. The Metropolitan was able to borrow the sofa, and with the Cooper Hewitt's approval, remove its cover and send it to the New York furnishing fabric company Scalamandre to be the model for new coverings for the Foot suite. However, the fabric was power-loom woven as a linen and wool rep (ribbed) fabric rather than being much more costly hand-woven wool like the original. The colors were also slightly modified; and the red was lightened and although there were several written references to the designs being white, they were woven in a color scheme more like that of the Copper Hewitt sofa. Only the seat medallions and trim found on the sofa were rewoven, so the Foot couches now have plain red fabric backs and seats, rather than being patterned as they were originally.

Left: Attributed to Duncan Phyfe, Couch, ca. 1837, in partial original fabric. Photograph, ca. 1939. Nancy McClelland Archive, Cooper Hewitt, National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution; Right: Textile for seat cover, ca. 1820-30. French. Wool, tapestry weave. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

Minard Lafever

Minard Lafever (1798–1854) was one of the most influential designers and architects in the United States from the 1830s through the 1850s. In the first decades of the nineteenth century, the country lacked professionally trained architects. Instead, local builders and carpenters relied on practical knowledge learned through apprenticeships and drew inspiration from pattern books and other design publications. During the eighteenth century, most of the popular design and pattern books were authored and published in Europe, but by the turn of the nineteenth century, creative American designers, builders, and draftsmen, like Lafever and others, began producing their own influential architectural reference books.

One of the most influential of these designers from the 1830s through the 1850s was Minard Lafever. Born in New Jersey, Lafever grew up in the Finger Lakes region of New York, and various accounts of his life suggest he received practical training in carpentry and building rather than a formal architectural education. He first appears in the New York City commercial directories in 1828, with his profession listed as "carpenter." Despite the successful publication of his first book, The Builder's General Instructor, in 1829, Lafever did not identify himself as an "architect" in the city directory listings until 1831. He went on to publish several other books on architecture and interior design, and his most popular titles, The Modern Builder's Guide (1833) and The Beauties of Modern Architecture (1835), were both reprinted multiple times during his lifetime. Both books included original Greek Revival designs for exterior elevations, floor plans, and interior architectural details on a bold scale and based on an archaeologically informed decorative vocabulary. In the preface to The Modern Builder's Guide, Lafever acknowledged the influence of Scottish architect and engineer Peter Nicholson (1765–1844), as well as The Antiquities of Athens (Vol. 1, 1762–1830) by Nicholas Revett and James Stuart, a multivolume illustrated title that provided the first survey of surviving ancient Greek architecture based on precise, measured drawings made on location.

Despite the significant influence his Classical designs had on the architecture of the period, Lafever worked in a variety of styles—including the dawning Gothic Revival—in his own architectural practice. Perhaps one of his best known extant buildings is the Church of the Holy Trinity (now St. Ann and the Holy Trinity) in Brooklyn, New York, built between 1843 and 1848. The Gothic Revival church includes an impressive program of sixty stained-glass windows, one of which is in the Museum's collection (see 2019.569)

Image: Engraved by J.P. Davis & Speer, after Charles E. H. Bonwill, (b. ca. 1836). P.E. Church of the Holy Trinity, (corner of Clinton and Montague Streets). Wood engraving, 23.4 x 16.2 cm. From The New York Public Library

Duncan Phyfe

The Shop and Warehouse of Duncan Phyfe, 168–172 Fulton Street, New York City. ca. 1816. Watercolor, black ink, and gouache on white laid paper. 15 7/8 x 19 5/8 in. (40.3 x 49.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1922 (22.28.1)

Duncan Phyfe (1770–1854) operated a prominent New York City cabinetmaking shop between 1792 and 1847. Born in Scotland, Phyfe was trained in his craft after immigrating to the United States in the 1784. He settled with his family in Albany before relocating to New York City in 1791. His interpretation of the English Neoclassical and Regency styles— examples of which are on view in the Richmond Room—dominated New York furniture design in the early nineteenth century, and he was the most sought after cabinetmaker in the city for much of his career. A watercolor rendering, ca. 1816, of Phyfe's shop and warehouse illustrates the place that many of New York's wealthy residents frequented for their furnishing needs. In addition to supplying furnishings for New York clients, Phyfe sold his fashionable furniture to wealthy planters and merchants in the American South and the Caribbean. By the 1830s his workshop embraced the popular Grecian Plain style, reflected in the furniture on view in the Greek Revival Parlor. More than a craftsman, Phyfe operated a successful business and owned the land that held his Partition Street (later Fulton Street) workshop, as well as other properties in Manhattan. His surviving body of work suggests that he employed a robust staff of cabinetmakers, turners, carvers, gilders, varnishers, caners, upholsterers, and likely lumbermen, sawyers, and veneer cutters.

In 1837, the year Samuel A. Foot probably purchased his suite of seating furniture, Phyfe formalized a partnership with his two sons, James D. and William Phyfe. The partnership of D. Phyfe & Sons lasted only a few years, and the firm's name changed to D. Phyfe & Son when William withdrew from the company in 1841. The year 1837 also brought a major financial panic and the beginning of a depression during which the cabinetmaking trade was hard hit. Newspapers advertised sales intended to reduce the firm's stock and suggest that, although Phyfe continued to be well regarded, the final years of his workshop did not mirror its earlier successes. Phyfe closed his workshop in 1847, just as the New York cabinetmaking industry was entering another period of significant transition with the arrival of large numbers of highly skilled émigré craftsmen from continental Europe and the increased popularity of the ornately carved Gothic and Rococo Revival styles—two idioms Phyfe appears to have never fully embraced.

Samuel A. Foot

The elegant suite of seating furniture attributed to the workshop of Duncan Phyfe on view in the Greek Revival Parlor was made for Samuel A. Foot, a prominent New York lawyer who served as the district attorney of Albany under Governor DeWitt Clinton and a judge on the Court of Appeals under Governor Washington Hunt. He also drafted resolutions condemning the verdict of Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), in which the US Supreme Court ruled that all people of African descent, free or enslaved, were not US citizens and therefore had no right to sue for their emancipation in federal court.

Image: Samuel Alfred Foot, frontispiece from his Autobiography: Collateral Reminiscences, Arguments in Important Causes, Speeches, Addresses, Lectures and Other Writings of Samuel A. Foot, LL.D. 2 vols (1873).

In 1818 Foot married Mariam Fowler (1797–1832); they had one daughter who died in infancy. Between 1828 and 1829 the couple relocated to New York City, where Foot continued to practice law. Two years after Mariam's death in 1832, Foot married Jane Campbell (1809–1867). The couple had fourteen children together. To house his growing family, Foot in 1835 embarked on building a large new residence at 678 Broadway, which, he later wrote, "has occupied too many of my thoughts…. A wise man will never build a house."

When the house was completed in 1837, Foot recalled that "furnishing our new house, arrangements to move and moving into it, necessarily took portions of my time." Though it has been suggested that the Phyfe furniture may have adorned Foot's law office, based on the function and style of the set, it is more likely the suite graced the principal rooms of his new home. The builder, exterior appearance, and interior arrangement of this house remains unknown. However, it was common in the period for furniture to harmonize with its surroundings, suggesting that the house was likely in a related Greek Revival style. In 1847 the Foot family relocated to Geneva, New York, and sold the Broadway house to Foot's nephew, Thomas A. Davies. The Phyfe suite likely furnished the family's new dwelling, a palatial Grecian-style villa named Mullrose (extant, though altered) on Delancey Drive in Geneva. Following Foot's death in 1878, the Phyfe furniture passed to his eldest daughter, Euphemia (1837–1920), who had married the Hudson River School artist Thomas Worthington Whittredge (1820–1910). Surviving photographs show some of Foot's furniture in the parlor of Hillcrest, the Whittredges' Summit, New Jersey, home, around 1900. The furniture continued to descend through the family to their daughters Olive W. Whittredge (1875–1957) and Mary Whittredge Katzenbach (1879–1965) until it entered The Met's collection in 1966.

Image: Interior view of the parlor at Hillcrest, the Summit, New Jersey, home of Worthington and Euphemia Foot Whittredge. Photograph, ca. 1900. American Wing curatorial files.

Suite of seating furniture

Left: Attributed to the Workshop of Duncan Phyfe (American, born Scotland 1770–1854) or D. Phyfe & Sons (1837–40).Side chair. New York, ca. 1837. Mahogany, ash, cherry, modern upholstery. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, L. E. Katzenbach Fund Gift, 1966 (66.221.5) Right: Phyfe's side chairs in the Foot suite closely resemble this earlier design from Pierre de La Mésangère. Edited by Pierre de La Mésangère (French, Pontigné 1761–1831 Paris). Detail of Plate 543, Collection de Meubles et Objets de Goût, vol. 3, Published by Au Bureau du Journal des Dames et des Modes, Paris, 1820–31. Engraving, hand-colored, 16 1/8 x 11 3/8 x 2 1/8 in. (41 x 29 x 5.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1930 (30.80(3))

The expansive suite of ten pieces of seating furniture on view in Greek Revival Parlor includes a pair of couches with scrolled ends of unequal heights, two taborets (stools), two window seats, and four side chairs. Attributed to the workshop of Scottish-born American cabinetmaker Duncan Phyfe, the suite was made to furnish lawyer Samuel A. Foot's New York City town house at 678 Broadway, completed in 1837. The complete original suite was even larger—from numerical markings on the side chairs, it is known that there were originally a dozen of them. The ten objects on view, along with two additional taborets (1972.264.1–.2), came to the Museum from Samuel Foot's descendants. Each different type of seating had a prescribed use: the side chairs would have offered the household a more upright option for sitting around a table, while the light and easily moved taborets may have been mobilized as occasional seating for female guests. The high scrolled armrests at the opposite ends of the two couches would have encouraged comfortable repose—or even a midday nap.

Attributed to the Workshop of Duncan Phyfe (American, born Scotland 1770–1854) or D. Phyfe & Sons (1837–40). Couch. New York, ca. 1837. Mahogany, pine ash, modern upholstery. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, L. E. Katzenbach Fund Gift, 1966 (66.221.1)

From the 1820s to the 1840s, designers and furniture makers embraced a revival of Classical prototypes from ancient Greek and Roman architecture and decorative arts and developed the distinct Grecian Plain style, defined by a robust architectural presence; sleek, curvaceous lines, and dramatic, figural mahogany veneers like those exhibited on the Foot suite. American cabinetmakers were particularly influenced by French interpretations of this style, and such designs were widely circulated through publications and journals, especially Pierre de La Mésangère's Collection de Meubles et Objets de Goût (1820–1831).

Advertisements in New York newspapers in this period frequently indicate the prevalence of Grecian Plain style furniture in the French taste, such as the chaise gondole (commonly called "French chairs" in New York) similar to those in the Foot suite. Characterized by a deep concave back and in-swept stiles that extend forward to the front seat rail, these examples display the newly revived cabriole leg. As early as 1825, New York makers produced this style of French chair, directly inspired by a design from Mésangère's Meubles. A popular style, French chairs are featured in an 1833 broadside advertisement by Joseph Meeks & Sons, which offered them for sale for $12 each. Duncan Phyfe, too, clearly capitalized on the popularity of the form.

Left: Attributed to the Workshop of Duncan Phyfe (American, born Scotland 1770–1854) or D. Phyfe & Sons (1837–40). Taboret. New York, ca. 1837. Mahogany, ash, modern upholstery. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, L. E. Katzenbach Fund Gift, 1966 (66.221.7) Right: Attributed to the Workshop of Duncan Phyfe (American, born Scotland 1770–1854) or D. Phyfe & Sons (1837–40). Window seat. New York, ca. 1837. Mahogany, ash, pine, modern upholstery. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, L. E. Katzenbach Fund Gift, 1966 (66.221.10)

Armchair

The plush high back with crotch-veneered tablet and sweeping scrolled arms of this sleek, mahogany chair illustrate the Phyfe workshop’s experimentation with variations of French fauteuils. The Phyfes’ inspiration may have emerged from the popular designs by Pierre de La Mésangère in his serial Collection de Meubles et Objets de Goût. The armchair, one of a pair, bears resemblance to number 638 “Fauteuil de Salon” in volume one (1802–07) of Meubles and number 320 “Fauteuil d’Appartament,” also in volume one (1810–12). According to family tradition these chairs stood in Duncan Phyfe's house on Fulton Street before descending to his great-granddaughter, Emma Phyfe Purdy (b. 1855), then to subsequent owners.

The plush high back with crotch-veneered tablet and sweeping scrolled arms of this sleek, mahogany chair illustrate the Phyfe workshop’s experimentation with variations of French fauteuils. The Phyfes’ inspiration may have emerged from the popular designs by Pierre de La Mésangère in his serial Collection de Meubles et Objets de Goût. The armchair, one of a pair, bears resemblance to number 638 “Fauteuil de Salon” in volume one (1802–07) of Meubles and number 320 “Fauteuil d’Appartament,” also in volume one (1810–12). According to family tradition these chairs stood in Duncan Phyfe's house on Fulton Street before descending to his great-granddaughter, Emma Phyfe Purdy (b. 1855), then to subsequent owners.

Image: Attributed to the Workshop of Duncan Phyfe (American, born Scotland 1770–1854). Armchair. New York, 1830–35. Mahogany, pine, cherry, ash, 38 x 21 1/4 x 25 1/2 in. (96.5 x 54 x 64.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Alfred Joltin, in memory of Ida Louise Opdycke, 1971(1971.128.2)

Secretary (Secrétaire à abattant)

The rippling figure of mahogany veneers sheaths the classically inspired columnar supports and architectonic mass of this secrétaire à abattant, or “French secretary” as identified in the 1834 New York cabinetmakers’ price book. In the 1830s and 40s, the Phyfe workshop embraced the revival of Grecian designs and use of flashy veneering techniques popularized by their French counterparts. The Phyfe workshop produced very few secrétaires but may have based this form on number 368 of volume one (1813–15) in Pierre de La Mésangère’s Collection de Meubles et Objets de Goût. The secrétaire employs sophisticated hardware such as spring-locked drawers for the safekeeping of valuables and a drop-front with a weighted iron balance hinge.

Attributed to the Workshop of Duncan Phyfe (American, born Scotland 1770–1854), D. Phyfe & Sons (1837–40), or D. Phyfe & Son (1841–47). Secrétaire à abattant. New York 1835–47. Mahogany, yellow poplar, white pine, gilded brass, mirrored plate glass, marble, ivory, 62 x 39 1/4 x 18 7/8 in. (157.5 x 99.7 x 47.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Manney Collection Gift, 1983 (1983.225)

Pier table

Left: Attributed to the Workshop of Duncan Phyfe (American, born Scotland 1770–1854), D. Phyfe & Sons (1837–40), or D. Phyfe & Son (1841–47). Pier Table. New York, 1835–40. Mahogany, marble, glass, 35 7/8 x 42 1/4 x 18 7/8 in. (91.1 x 107.3 x 47.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Edgar J. Kaufmann Foundation Gift, 1968 (68.201a, b) Right: Edited by Pierre de La Mésangère (French, Pontigné 1761–1831 Paris). Detail of Plate 631, Collection de Meubles et Objets de Goût, vol. 3, Published by Au Bureau du Journal des Dames et des Modes, Paris, 1820–31. Engraving, hand-colored, 16 1/8 x 11 3/8 x 2 1/8 in. (41 x 29 x 5.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1930 (30.80(3))

Designated for the pier wall between two windows, a pier table was considered an integral part of an elegant parlor. The mirror below the tabletop reflected light into the room, amplifying the soft glow of candle and fuel-based light sources. Two similar Phyfe pier tables are known: one, for which there is an 1834 bill of sale, is in the White House; the other, bearing the D. Phyfe & Sons label (1837–40), was made for Phyfe's daughter Eliza Phyfe Vail (1801–1890). However, neither of those examples have scroll supports placed at a 45 degree angle to the table's top as seen in this example. The other two documented tables have scroll supports and bases that face straight out. This table carefully follows the design illustrated in Plate 631 of volume three (1820–31) of Pierre de La Mésangère's Collection de Meubles et Objets de Goût.

Pair of looking glasses

Two looking glasses (1979.393.1-.2) on view in the Greek Revival Parlor, Gallery 738.

In the design of this looking glass, sculptural fleur-de-lis corner brackets are accompanied by repeating Neoclassical bands and acanthus-like motifs to frame an impressive length of mirrored plate glass. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, large glasses aided in the amplification of sun- and lamplight within a room. They were often placed either horizontally over fireplaces or vertically between windows. This looking glass, one of a pair (see 1979.393.2), bears some stylistic and construction similarities to labeled examples from the shop of Isaac L. Platt, a looking-glass manufacturer and retailer active from 1815 to 1843 on Broadway in New York City.

Keep Learning

American Revival Styles, 1840–76

Read more about American revival styles in the nineteenth century in this Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History essay.

Duncan Phyfe (1770–1854) and Charles-Honoré Lannuier (1779–1819)

Read more about the furniture making of Duncan Phyfe, whose work is on display in the Greek Revival Parlor, in this Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History essay.