Benkard Room

Petersburg, Virginia, ca. 1811

Matthew Thurlow, Research Associate; and Moira Gallagher, Research Associate

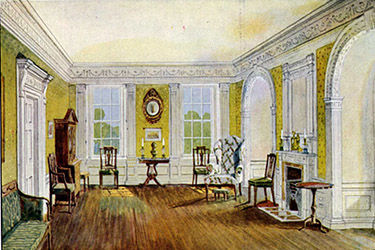

This parlor, installed in Gallery 725, comes from a house built in Petersburg, Virginia, in 1811, but prominently features furniture made in New York City from the same period. Many pieces once belonged to the noted early-twentieth-century collector Bertha King Benkard (1877–1945) and were donated to The Met after her death. In 1980, the Museum renamed the Petersburg Room in her honor and furnished the gallery with her collection, rather than objects that would have likely occupied a Petersburg interior in the early years of the nineteenth century. Like the nearby Baltimore and Haverhill Rooms, the Benkard Room exemplifies the popularity of Robert and James Adam's Neoclassical taste in the young United States.

An alternate view of the Benkard Room in the American Wing.

Provincial Neoclassicism

Composition ornament of a shepherd and his flock applied to the Benkard Room's wooden overmantel.

The architectural elements of the Benkard Room are from the first-floor parlor of a Petersburg, Virginia, house originally built in 1811 for William Moore, an Irish-born pharmacist. The carved woodwork and composition ornament offer a powerful interpretation of the Adamesque Neoclassical style.

Setting

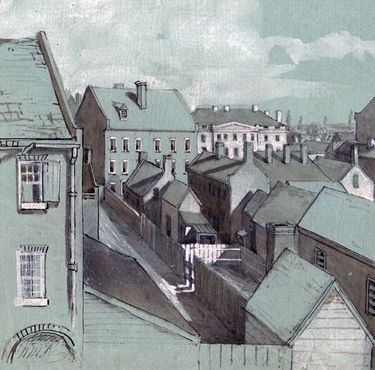

The port of Petersburg, Virginia, was an important commercial center in the nineteenth century. Its location at the headwaters of the Appomattox River was ideal for processing and transporting goods. Much of the cotton, tobacco, and metal produced in southern Virginia and northern North Carolina passed through the town.

By 1810, the population of Petersburg was almost six thousand, which included a prosperous middle class of merchants and a landed gentry, both with close ties to more cosmopolitan cities in the North as well as connections to England and Scotland. Enslaved Africans and African Americans, however, comprised nearly forty percent of the city's population, and it was their labor that cultivated and transported the cash crops that fueled Petersburg's economy. An English traveler visiting Petersburg in 1807 remarked that the city "is a place of considerable wealth and importance, carrying on a great trade in tobacco and flour, a considerable portion of which is with New York."

Image: William Murray Robinson (1807–1878), Petersburg / 13th Nov 1836, Gouache on paper. Petersburg Museums, Va

Exterior

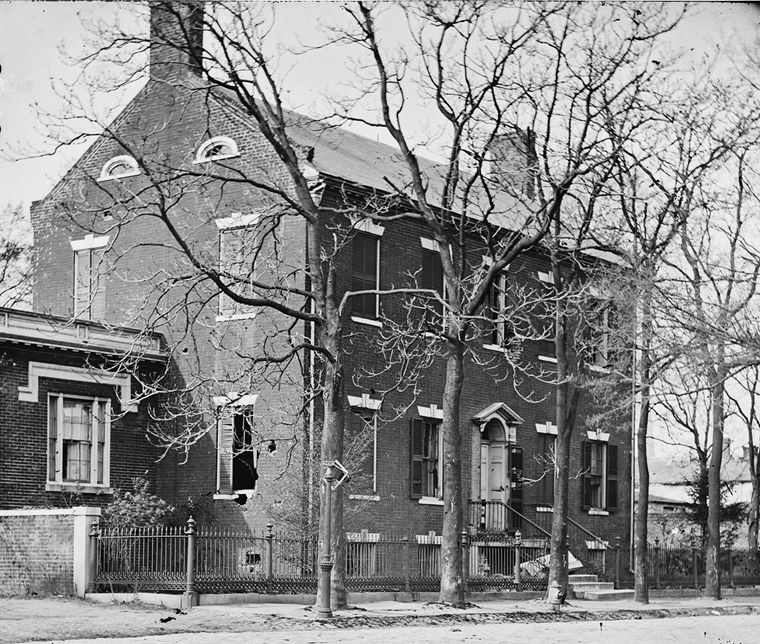

A house on Bollingbrook Street, Petersburg, Virginia. This photograph, taken around 1865, shows damage incurred during the Civil War siege of the city. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

According to its earliest fire insurance policy, the Moore House, from which this room was taken, it was a five-bay, one-room-wide brick structure. Its two stories were topped by a roof made of wood, with a pediment along the front facade and a rear porch.

Although there are no known photographs of the Moore House, the facade probably looked something like the structure shown here. It had an arched fanlight over the front door and stone lintels with keystones above each window. Although many single-pile homes included an attached ell in the back for a kitchen, pantry, and additional sleeping quarters, there is no evidence that the Moore House had such an addition.

Interior

Each of the Moore House's two floors had a center hall with a room on either side. The Benkard Room's interior was taken from the parlor, which originally had windows on the fireplace wall and the two adjacent walls. The doorway leading to the Baltimore Dining Room approximates the location of the original, which provided access to the hallway and the stairs.

Numerous details suggest that the builder of the Moore House lacked a thorough understanding of architectural design and proportion. For instance, the use of composition ornaments is excessive, and the cornice and arched niches are awkwardly juxtaposed, as are the pilasters flanking the windows within the niches. Elaborate mantels and overmantels were typical of Petersburg houses built in the early nineteenth century.

Image: A trained architect would not have designed a room with niches that interrupt the cornice as they do in the Benkard Room.

Changes over time

The original owner, William Moore, occupied the house only from 1811 to 1814. In 1821 and 1822, the second owner, Johnston Henderson, made improvements that probably included the marble mantel seen in the room today. It served as a rental property for much of the nineteenth century.

From the mid-nineteenth century on, fortune was not kind to the house. It was badly damaged in 1864 and 1865 during the Siege of Petersburg, the last major standoff of the Civil War, in which the Union Army pummeled the city with heavy cannon and mortar fire. The Moore House was hit nine times. Just fifty years later, in 1916, it was razed to make way for a gas station. Today, the site is a vacant lot.

Image: The carved marble mantel, likely of English or Italian origin, was probably added to the parlor of the house during Henderson's ownership.

William Moore

William Moore, the original owner of this room, and his brother Robert moved to Petersburg, Virginia, from Ireland in the 1790s. William was a pharmacist, and Robert found success as a merchant and tobacco warehouseman. William built his house on land purchased in 1801 from Robert and rented space from his brother before he moved into his new home in 1811. That same year, William served as mayor of Petersburg.

William Moore occupied his stately brick dwelling for only three years. After selling it in 1814, he operated a "vendue" store, an auction house for imported and second-hand goods. He died in 1835.

House for rent

In 1814, William Moore sold his home to Johnston Henderson, the first of nine successive proprietors to rent out the house. Henderson made a series of improvements in 1821 and 1822, including the installation of a carved marble mantel. The dwelling's high value restricted potential tenants to Petersburg's more affluent residents. The city's tax rolls frequently refer to it as a mansion.

Image: Johnston Henderson's mantel, which depicts the Greek myth of Leda and the Swan.

Bertha King Benkard

Bertha King Benkard (1877–1945) was a member of twentieth-century New York society, and a pioneering tastemaker and collector of American decorative arts. Born Bertha King Bartlett, she married Henry Horton Benkard in 1903 and began actively collecting American antiques and salvaging historic architecture. Her residence in Oyster Bay, Long Island was outfitted with her impressive collection, which focused on works created during the early nineteenth century, of furniture, silver, ceramics, glass, fine arts, and architectural elements. By the 1930s and 1940s, she was considered one of the leading experts in American antiques and shared her expertise with numerous historic organizations and fellow collectors, including Henry Francis du Pont. Upon her death in 1945, friends and family formed the Bertha King Benkard Memorial Fund to commemorate her legacy. They selected a room from her Long Island estate that featured architectural paneling from a house in Newburyport, Massachusetts, and donated it to The Met, along with its furnishings. As the American Wing evolved in subsequent decades, the architectural elements from Newburyport were deaccessioned, and the furnishings were moved into Petersburg Room, which was renamed in honor of Benkard.

A collector's room

The Benkard Room is a complex intermingling of The Met's purchase of architectural woodwork in the 1910s and a large gift of decorative arts in the 1940s. The Museum purchased the Moore House parlor in 1916, and it was one of the original period rooms when the American Wing opened in 1924. Initially referred to as the Petersburg Room, the parlor was renamed the Benkard Room in 1980 in honor of Bertha King Benkard, whose large collection of objects, now displayed there, was presented to the Museum in 1946.

Image: The Petersburg Room as shown in the 1925 publication The Homes of Our Ancestors, by R. T. H. Halsey and Elizabeth Tower.

Acquiring the Benkard Room

Durr Friedly, curator of decorative arts at The Met, purchased the woodwork of the Moore House in 1916 from J. K. Beard, a Richmond antiques dealer, during an extended buying trip through Virginia. According to Friedly, the room represented "the best example of [composition] decoration discovered in the South."

When the Museum acquired the woodwork, almost all of the composition ornament seen on the cornice was gone, but the original elements left outlines that indicated their design and location.

Image: The Petersburg Room being installed at The Met around 1923, prior to the restoration of the composition ornament on the cornice.

On exhibit

The Petersburg Room, as installed in 1924 without its marble mantel and overmantel.

This period room has undergone many changes in its near century at The Met. It was first installed as the Petersburg Room in 1924, and furnished with Federal-style furniture from New England and the Middle Atlantic states. Although Petersburg, Virginia, had supported an active furniture-making industry, the Museum did not own any Virginia pieces. In 1980, the room was refurnished with objects from the Benkard Collection and renamed the Benkard Room.

Although the room's proportions remain true to its original location, its orientation has been altered. The Moore House was just one room deep and originally had two windows on the fireplace wall as well as on both adjacent walls.

The mantel

The marble mantel and wood overmantel installed in the Petersburg Room.

The original wood overmantel and marble mantel from the 1820s were not part of the Museum's purchase of the Moore House parlor. At the beginning of the twentieth century, a Petersburg nurse named Mary Brown, who owned the house at the time, removed these two elements and presented them to a friend who was interested in local architecture. When the American Wing opened in 1924, the Petersburg Room featured a replacement mantelpiece between the arched niches and no overmantel.

A year later in 1925, the marble mantel and original overmantel from the house arrived as a gift to the Museum and were quickly installed in the room. Unfortunately, the overmantel was installed incorrectly. The frieze panel with scrolling flowers should sit directly on top of the marble mantel.

The Benkard Collection

The original Benkard Room as installed in 1947, featuring the architectural elements from a Newburyport, Massachusetts, house.

In the 1940s, the Bertha King Benkard Memorial Fund gave the Museum much of the furniture on display in this room, as well as the parlor woodwork of a Newburyport, Massachusetts, house built in 1807. Benkard had purchased the Massachusetts interior in 1938 and set it up in her Oyster Bay, New York, home. The Newburyport Room was installed at the Museum in 1947 but removed and deaccessioned in 1976 to allow for the installation of the Richmond Room.

A large portion of the Benkard furnishings were transferred to the Petersburg Room during the renovation of the American Wing in the late 1970s, and the room was renamed in Benkard's honor in 1980.

Redecorating the Benkard Room

The Benkard Room, photographed in 1984.

Two dramatic changes were made to the room's appearance for its reopening in 1980. The 1924 room, as described in A Handbook of the American Wing by R. T. H. Halsey and Charles O. Cornelius, had walls covered "with old bright yellow satin brocade of a shade and design very popular in the period. Rooms hung with silk fabrics were not uncommon, particularly in the southern and middle states." On view for more than fifty years, the already "old" satin fabric had deteriorated and was removed. Later research indicated that only the most the exceptional homes in the United States had walls lined with silk. Most had either painted or papered walls.

In the original installation, the room's floors were bare wood, yet rooms in fine houses in the Federal era were rarely uncarpeted. For the room’s reopening, curator Berry B. Tracy took inspiration from a large handmade wool cross-stitched carpet (23.62) in the American Wing’s collection. Created by two sisters from Champlain, New York, for their father's home between 1808 and 1812, the carpet is decorated with pink roses in a latticework pattern on a field of green, bordered by a Greek key pattern surrounded by seashells. It is notched at the top to accommodate the fireplace hearth. For the Benkard Room, the handmade carpet was reproduced as loom-woven looped-pile Brussels carpeting, which would have been appropriate for a home’s best room in the nineteenth century. The carpet's palette informed the room's new lively green painted walls and crisp white cotton curtains.

Image: Details of latticework and Greek key border. Ann Moore, Carpet, 1808–12. Wool, embroidered in cross-stitch. 188 x 224 in. (477.5 x 569 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Miss Isabelle C. Mygatt, 1923 (23.62)

Colonial Revival elegance

Bertha King Benkard's collection of New York furniture in her Long Island residence. "1109P9, Rose Residence, L.I., 1945," Fay S. Lincoln Photograph Collection, 1920-1968 (1628). Historical Collections and Labor Archives, Eberly Family Special Collections Library, Pennsylvania State University Libraries, Pennsylvania State University. Image courtesy of Hagley Museum and Library.

Many of the objects on display here were purchased from the collection of the room's namesake, Bertha King Benkard, and then presented to the Museum by a group of her friends in 1946. Benkard's house on Long Island was a showcase for American furniture, European lighting devices, Chinese porcelain, and other imported decorative arts.

As a tribute to Benkard's role as a pioneering collector of Americana, this room is not furnished as the original owner William Moore's house might have been. Instead, it reflects Benkard's personal taste, serving as an example of the Colonial Revival aesthetic common to museum period rooms decorated in the first half of the twentieth century.

Liberty

Painted in China for the American market, this verre églomisé image is based on a 1796 engraving by Edward Savage of Philadelphia. The goddess of liberty stands tall, with Boston Harbor in the distance—a reference to the city's important role in the American Revolution. As she offers a cup to a bald eagle, the recently adopted symbol of the United States, Liberty tramples the key to the Bastille in Paris and the star of the Order of the Garter of Great Britain, representing the end of the French monarchy and the United States' freedom from England.

Image: Liberty. Chinese, for American market, ca. 1800. Verre églomisé. 20 3/4 x 15 1/2 in. (52.7 x 39.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Members of the Committee of the Bertha King Benkard Memorial Fund, 1946 (46.67.85)

Inspiration and origin

The secretary's overall design stems from George Hepplewhite's Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer's Guide (1788). Although the secretary's figured mahogany and geometric exterior design suggests a Philadelphia origin, the extravagant satinwood interior, with its large, inlaid shell, relates more closely to Baltimore work. Because of the cities' close proximity to each other, craftsmen often moved between them.

This secretary is a highlight of the Museum's Federal furniture collection. The repetition of oval panels of mahogany veneer is a hallmark of the Neoclassical style. The combined desk and bookcase offered an efficient means of conducting correspondence, managing household accounts, and storing the family's books. It was also a symbol of education and literacy. Such pieces were often located in public spaces such as parlors and dining rooms, where they could be on full display for guests.

Top: Secretary and bookcase. Baltimore, Maryland or Philadelphia, 1795–1810. Mahogany, satinwood, ebony with white pine, cedar. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Members of the Committee of the Bertha King Benkard Memorial Fund, 1946 (46.67.89)

Top: Secretary and bookcase. Baltimore, Maryland or Philadelphia, 1795–1810. Mahogany, satinwood, ebony with white pine, cedar. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Members of the Committee of the Bertha King Benkard Memorial Fund, 1946 (46.67.89)

Left: Interior of secretary showing its marquetry shell. Right: Plate 44 in George Hepplewhite's Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer's Guide (1788)

Merging designs

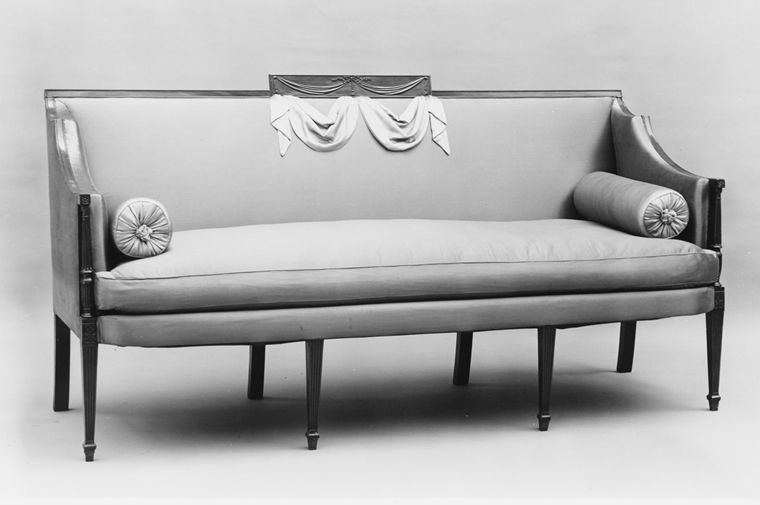

Sofa. New York City, 1800–1805. Mahogany with ash, yellow poplar. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Members of the Committee of the Bertha King Benkard Memorial Fund, 1946 (46.67.90a-d)

The square-back sofa with swept arms is a distinctive type of furniture made in New York City in the first decade of the nineteenth century.

This sofa combines two patterns found in George Hepplewhite's Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer's Guide (1788). The carved swag on the crest-rail tablet is a common Neoclassical motif and also appears on seating designs found in Hepplewhite’s guide.

Image: Plate 23 and Plate 9b in George Hepplewhite's Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer's Guide (1788)

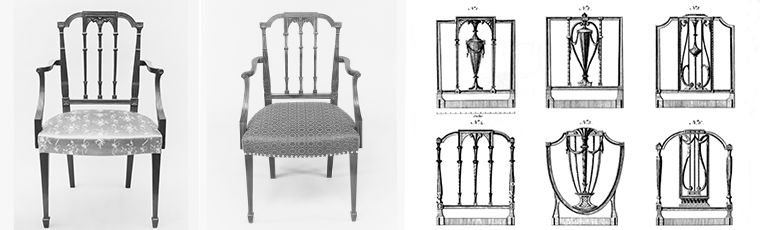

English design in the United States

Left: Set of chairs. New York City, 1795–1810. Mahogany with ash, cherry. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Members of the Committee of the Bertha King Benkard Memorial Fund, 1946 (46.67.97-.99, .101, .102, .104); Right: Plate 36 in Thomas Sheraton's Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer's Drawing-Book (1793)

Like that of many of the furnishings on view in the Benkard Room, the design of this set of chairs was inspired by drawings published in London. In this case, the source was number 4, plate 36, in Thomas Sheraton's Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer's Drawing-Book (1793).

While Sheraton's designs were also used in other American cities, New York cabinetmakers and their customers were particularly fond of options 1 and 4 on plate 36. Although these chairs are displayed in a parlor setting, they may also have been used in a dining room. Chairs were typically bought in multiples of six, with one armchair for every five side chairs, The six chairs on view in the Benkard Room most likely represent part of a set of twelve.

Pair of window benches

Attributed to the workshop of Duncan Phyfe (1765–1854). Pair of window benches, 1805–1815. Mahogany with cherry. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Steven Lorillard, 1953 (53.179.2-.3)

The carved thunderbolts seen on the crest rails of this pair of window benches are found on seating furniture documented to the workshop of Duncan Phyfe. Like most decorative motifs on furniture of the early nineteenth century, the thunderbolt is linked to classical mythology as an attribute of the Greek god Zeus.

Drop-leaf pembroke table

Of a type allegedly named for the ninth Earl of Pembroke, the Englishman Henry Herbert (1693–1751), a noted connoisseur and amateur architect, this small table features two drop leaves and a drawer. It was ideal for small, informal meals or for taking tea.

Image: Drop-leaf Pembroke table. New York City, 1795–1805. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, satinwood, holly, ebony with maple, white pine, yellow poplar. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Members of the Committee of the Bertha King Benkard Memorial Fund 1946 (46.67.109a,b)

Pianoforte

Works by John Geib and Son (active 1804–15). Pianoforte, 1810–15. Mahogany, mahogany and rosewood veneers, satinwood, ivory, gilded gesso, brass with white pine, maple, ash. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Eric M. Wunsch, 1969 (69.259)

Instruments such as this pianoforte represent one of the most complex forms of case furniture manufactured by cabinetmakers in early-nineteenth-century New York.

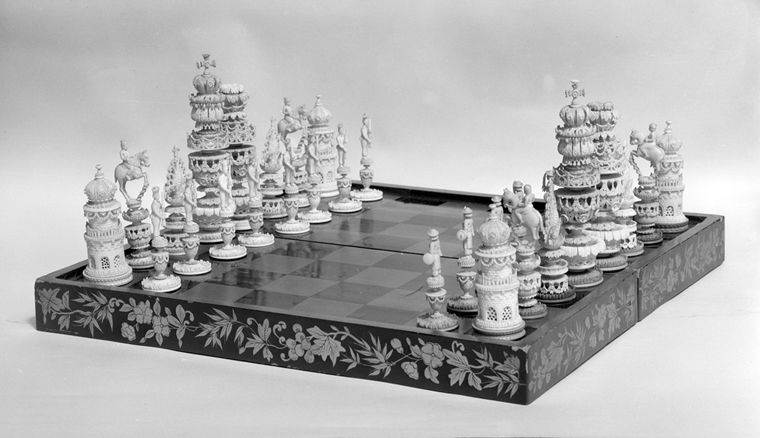

Chess set

Chess set. India, ca. 1800. Lacquered wood. Ivory. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Members of the Committee of the Bertha King Benkard Memorial Fund, 1946 (46.67.742 gg)

The game of chess probably originated in India, where ivory chess pieces have been found dating as far back as the eighth century. This set and board were made for the Western market but are distinguished from the majority of export pieces by their exquisitely intricate carving. The use of red and white figures instead of black and white is characteristic of sets produced in India.

Chandelier

Chandeliers were rarely found in early-nineteenth-century houses, but this example was a centerpiece of Mrs. Benkard's parlor at her home on Long Island and retained its prominence when her collection was installed at The Met in 1947.

Image: Chandelier. England, 1810–20. Glass, brass. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Members of the Committee of the Bertha King Benkard Memorial Fund, 1946 (46.67.144)

Pair of candelabra

This pair of candelabra was originally sold at the 1845 auction of the Bordentown, New Jersey, estate of Napoleon's brother Joseph Bonaparte (1768–1844). Appointed king of Naples in 1806 and king of Spain two years later, Joseph fled to New York City in 1815 after Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo. His elegant estate on the Delaware River, known as Point Breeze, contained a lavish collection of French fine and decorative arts.

The lower portion of each candelabrum, from the base to the candle sockets, is actually a late eighteenth-century candlestick, to which branches and a central shaft were added in the early nineteenth century.

Image: Pair of candelabra. France, 1790–1800, with later additions. Gilt bronze. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Members of the Committee of the Bertha King Benkard Memorial Fund, 1946 (46.67.77a-k, -78a-k)

Keep Learning

American Federal-Era Period Rooms

Read more about American Federal Era Period Rooms and English design influences in this Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History essay.

Duncan Phyfe (1770–1854) and Charles-Honoré Lannuier (1779–1819)

Read more about the furniture making of Duncan Phyfe, whose work is on display in the Benkard Room, in this Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History essay.