Rococo Revival Parlor

Astoria, Queens, New York, ca. 1850

Medill Higgins Harvey, Associate Curator of American Decorative Arts & Manager, Henry R. Luce Center for the Study of American Art

The Richard and Gloria Manney John Henry Belter Rococo Revival Parlor, installed in Gallery 739, presents a sumptuous mid-nineteenth-century parlor characteristic of affluent homes in the United States. It features furniture by one of the most innovative and virtuosic American cabinetmakers of the period in a room whose architectural elements—columnar screen, windows, doorway, doors, cornice, and rosette—are from the double parlor of a Classical Revival style villa built around 1850 in Astoria, Queens, for a prosperous businessman named Horace Whittemore (1813–1871). John H. Belter's laminated and elaborately carved furniture represents the height of fashionability and would have graced elegant parlors like that of the Whittemore House not only in the New York area, but also across the country.

An alternate view of the Rococo Revival Parlor.

Exterior

This parlor's architectural elements came from a three-story Classical Revival villa that stood on the corner of Perrot and Owen (later Franklin) Streets in what was an elegant new suburban community in Astoria, Queens. Named for John Jacob Astor, Astoria was incorporated in 1839. Horace Whittemore, whose father, Homer (1787–1858), was one of the founding officers of the village of Astoria, purchased the lot in 1849. The grand house he built there had a raised basement and commanding full-height porticos with Corinthian columns on its front and back facades. When it was built, the house had unobstructed views of the East River. Horace Whittemore lived there with his wife, Catherine, their five children, and as many as six Irish-born servants.

Image: Postcard depicting the Whittemore/Larocque mansion, Astoria, Queens, New York. American Wing curatorial files

Neighborhood

Left: Detail of map of the village of Astoria, Queens Co. L.I, 1852. Published by E.T. Quititch. Hand-colored map. 37 x 44 in. (94 x 112 cm). From the New York Public Library. Right: Detail of map showing the Whittemore property on the left corner of the intersection.

Astoria offered an escape from the teeming crowds and frenetic activity of Manhattan and large lots on which to build villas, or spacious, freestanding family houses. Yet, it was an easy commute by boat across the East River to the city. Life in Astoria also provided a close, interconnected community. Many of the Whittemores' neighbors were relatives and business associates, including Horace's brothers Albert and Edward, business partner and brother-in-law John B. Reboul, and his mother's family, the Blackwells.

Josiah Whiney (1815–1896), the builder believed to have designed and executed the house, recounted his reminiscences of the area to a reporter for the Long Island Star Journal on January 4, 1895, recalling "the time when all along the East River shore and up around Bowery Bay there was nothing except the fine cottages of wealthy men and the place looked as Newport [Rhode Island] does today. Wealthy gentlemen of means lived along the shore from Ravenswood up through Astoria."

Interior

An inventory taken of the house at the time of Horace Whittemore's death in 1871 provides insight into the house's interior and how the spaces were used. Upon ascending the outside staircase at the front of the house, traversing the portico, and entering the first floor, visitors were welcomed into a central hall flanked on the right by a pair of formal parlors and on the left by a family living room and a billiards room. On the ground level below were the dining room, kitchen, and pantries. Five family bedrooms were located on the second floor, and the third floor, with its low ceiling and small horizontal slot windows, likely housed the servants' quarters.

A double parlor

Left: A view of the double parlor in the Whittemore/Larocque mansion before demolition, 1965. American Wing curatorial files. Right: A view of the Rococo Revival Parlor.

The pair of parlors on the first floor of the Whittemore House were separated by a columnar screen, which now graces the open end of the room. Distinguished by elaborate plasterwork cornices and ceiling rosettes, the rooms would have hosted various social gatherings. The southwest (inland facing) parlor contained an abundance of seating furniture, including multiple sofas and several different types of chairs, and tables. The southeast (river facing) parlor included a piano, sofa, numerous chairs, tables, and a music stand. The decoration of and activities in the parlor were typically the domain of the ladies of the house. Catherine Whittemore may well have been guided by the recommendation in Andrew Jackson Downing's The Architecture of Country Houses (New York, 1850) that a parlor, or drawing room, "…should always exhibit more beauty and elegance than any apartment in the house." At the time, a single style was typically not employed throughout a house's interior. Instead, each room was often a discrete environment, with the Gothic style favored for libraries and dining rooms and the Rococo Revival, also termed Modern French, preferred for parlors.

At The Met, the Whittemores' parlor is decorated in the recommended Rococo Revival style and showcases the furniture of master cabinetmaker and innovator John Henry Belter. In his discussion of furniture in The Architecture of Country Houses, A. J. Downing—though not fond of it—admitted that "Modern French furniture, and especially that in the style of Louis Quatorze, stands much higher in general estimation in this country than any other. Its union of lightness, elegance, and grace renders it especially the favorite of ladies." The design of this room follows Downing's suggestion that the parlor "…should be lighter, more cheerful and gay than any other room. The furniture should be richer and more delicate in design, and the colours of the walls decidedly light, so that brilliancy of effect is not lost in the evening."

Horace Whittemore (1813–1871) and Whittemore household

Horace Whittemore, born and raised in New York City and Queens, New York, made his fortune in the wholesale fur and hat business. By 1837, at the age of twenty-four, he was a partner in a New York City dry goods firm, Whittemore and Ladd. In 1840 he ventured to Saint Louis, where he set up a hat and fur business, H. and A. O. Whittemore, with his brother Albert. A few years later, Horace and Albert were joined by their brother Robert. The firm was renamed H. and R.B. Whittemore. Robert took charge of their operations in Saint Louis, while Albert and Horace established a branch of their business in New York City. They formed a partnership with their brother-in-law John B. Reboul, selling and shipping furs, pelts, and hatters' goods. The firm, Reboul and Whittemore and later H & R. B. Whittemore & Co., prospered, and in 1863 a third branch, similarly described as a wholesaler of hats, caps, furs, and other goods, opened in Chicago. Horace and his brothers managed their Chicago operations remotely, bringing in two local partners, John F. Carter and Samuel Brown. Tax records from 1865 further attest to Horace Whittemore's affluence, listing his income as in excess of $32,000 (roughly equivalent to $526,750 in 2020) and his taxable possessions as three watches, a piano forte, and 183 ounces of silver plate.

His professional success allowed Horace, his wife, Catherine, and their children, Maria, Emma, Kate, Horace, and Alfred, to enjoy a life of privilege. At their villa in Astoria, Horace and Catherine's household included between four and six servants at any given time. According to the census records, their servants were all born in Ireland. Individuals identified in the censuses include John Delaney, Elizabeth Flynn, Ellen Manning, Sarah Templeton, Catherine McQuade, Ellen Flood, James Williams, Catherine Murray, William Hanks, Ann Smith, Mary Fogarty, and a woman listed only as Bridget. Although no records of the specific duties these servants performed have been found, they would have cooked, cleaned, served food, tended the grounds, taken care of the horses and carriages, and likely helped care for the children. Circuit court records in Saint Louis indicate Horace Whittemore emancipated a thirty-two-year-old woman named Letty and her children Eloe, Maravenia, and Julia on December 9, 1848, before he built his New York home. Letty later appears in an 1856 list of licenses issued to free Black residents of Saint Louis and is described as "a washer by trade." Currently no more is known about Letty and her children or the individuals working as servants in the Whittemore home in Astoria.

Image: An advertisement for H. and R. B. Whittemore published in the Illinois Daily Journal, August 28, 1852, p. 3. Accessed through Illinois University Library, October 2020.

Joseph Larocque (1831–1908)

Horace Whittemore's widow, Catherine, sold the house and property to her brother-in-law Joseph Larocque on October 6, 1871. The purchase price was one dollar, suggesting the transfer was essentially a gift but required a cash exchange to issue a title. Joseph and his wife, Annie Whittemore Larocque (1832–1908), Horace Whittemore's sister, lived in the house with their extended family—four daughters, two sons, two women described in census records as "grandmothers," and six servants. The Larocques expanded the house with a sizable addition on its north side, as indicated on an 1873 map. The expansion did not change the double parlors, which remained intact until the house was demolished in 1965.

Horace Whittemore's widow, Catherine, sold the house and property to her brother-in-law Joseph Larocque on October 6, 1871. The purchase price was one dollar, suggesting the transfer was essentially a gift but required a cash exchange to issue a title. Joseph and his wife, Annie Whittemore Larocque (1832–1908), Horace Whittemore's sister, lived in the house with their extended family—four daughters, two sons, two women described in census records as "grandmothers," and six servants. The Larocques expanded the house with a sizable addition on its north side, as indicated on an 1873 map. The expansion did not change the double parlors, which remained intact until the house was demolished in 1965.

Image: Joseph Larocque, as pictured in Notable New Yorkers of 1896–1899 (New York: Moses King, 1899), p. 83.

Left: Detail of Astoria. Part of Long Island City, Town of Newtown, Queens Co. L.I., 1873. Published by Beers, Comstock & Cline. From the New York Public Library. Right: Detail of the map showing the Larocque property in the upper right corner.

Larocque was a prominent lawyer in New York City. Not long after being admitted to the bar in 1852, he partnered with Judge William G. Choate to create the firm of Shipman, Larocque & Choate on Wall Street, where he worked throughout his career. Larocque also served as president of the New York City Bar Association, was a director of several companies, including the American Cotton Oil Company, Niagara Falls Power Company, and Plaza Bank, and belonged to various clubs and civic institutions such as the Century Club and The Metropolitan Museum of Art. At his death, Larocque's estate was valued at more than $700,000 (in excess of twenty million dollars in 2020). His obituary in The New York Times described him as "a man of great intellect and commanding power."

Image: View of the Larocque mansion, undated, American Wing curatorial files

William Shipman (1818–1898)

At some point during the 1890s, Joseph Larocque sold the house to his law partner, Judge William Shipman, who resided there for the remainder of his life. A distinguished judge, revered professor of law at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, and successful and influential lawyer, Shipman presided over the 1861 trial of Captain Nathaniel Gordon, the only United States citizen to be executed for the crime of slave trading. When sentencing Gordon, Shipman made an impassioned statement, saying, "think of the cruelty and wickedness of seizing nearly a thousand fellow beings, who never did you harm, and thrusting them beneath the decks of a small ship beneath a burning tropical sun, to die in of disease or suffocation, or to be transported to distant lands, and be consigned, they and their posterity, to a fate far more cruel than death."

Image: William David Shipman, as pictured in Notable New Yorkers of 1896–1899 (New York: Moses King, 1899), p. 101.

Louis Molteni (born 1876) and Molteni Family

During the early decades of the twentieth century, Astoria experienced great growth and development. It was transformed by the building of shops, factories, and a plethora of smaller homes and apartment buildings. Increasing numbers of Irish and Italian immigrants settled in Queens between 1900 and 1920, as improved transportation via newly built bridges and tunnels facilitated commuting from Astoria to work in Manhattan. Although it is not known precisely when Louis Molteni acquired the house, records suggest he, his wife, Clotilde (born 1876), and his two children, Rita (1900–1980) and Sirio (1909–1989), were residing there by 1915. Louis immigrated to the United States in 1903 from Lucca, Italy. Born Luigi Molteni, he changed his name to Louis and applied for citizenship in 1927. He described his profession variously as a sales manager, office manager, and foreman of a cigar factory. The house remained in the Molteni family until it was demolished in 1965. Street names changed several times, and the address ultimately became 4-17 27th Avenue. Sirio Molteni and his sister, Rita, who married William Pooler, recognized the aesthetic and historical importance of the home in which they had grown up and wanted to preserve some of the house as its destruction loomed. They gifted the two parlors to The Met.

Image: Exterior of the mansion, under the ownership of the Molteni family, undated. American Wing curatorial files.

John Henry Belter (1804–1863)

This detail shows Belter’s showroom, which was located at 547 Broadway from 1853–61. Frederick Heppenheimer (d. 1876). Broadway from Spring to Prince St., 1855. Hand-colored lithograph. Museum of the City of New York (39.253.8)

Best known for his ornately carved, laminated, and steam-bent furniture in the Rococo Revival style, the German-born, New York cabinetmaker John Henry Belter revolutionized the field of cabinetmaking in nineteenth-century America. Born in Hilter, Germany, Belter immigrated to the United States in 1833 and settled in New York City. By 1844 he had become a naturalized citizen and established his own cabinetmaking workshop in lower Manhattan. Over the next decade, his business continued to grow, and in 1854, the firm incorporated as J. H. Belter and Co. with a showroom on Broadway and a large, two-building manufactory outfitted with steam power located uptown at East 76th Street and Third Avenue.

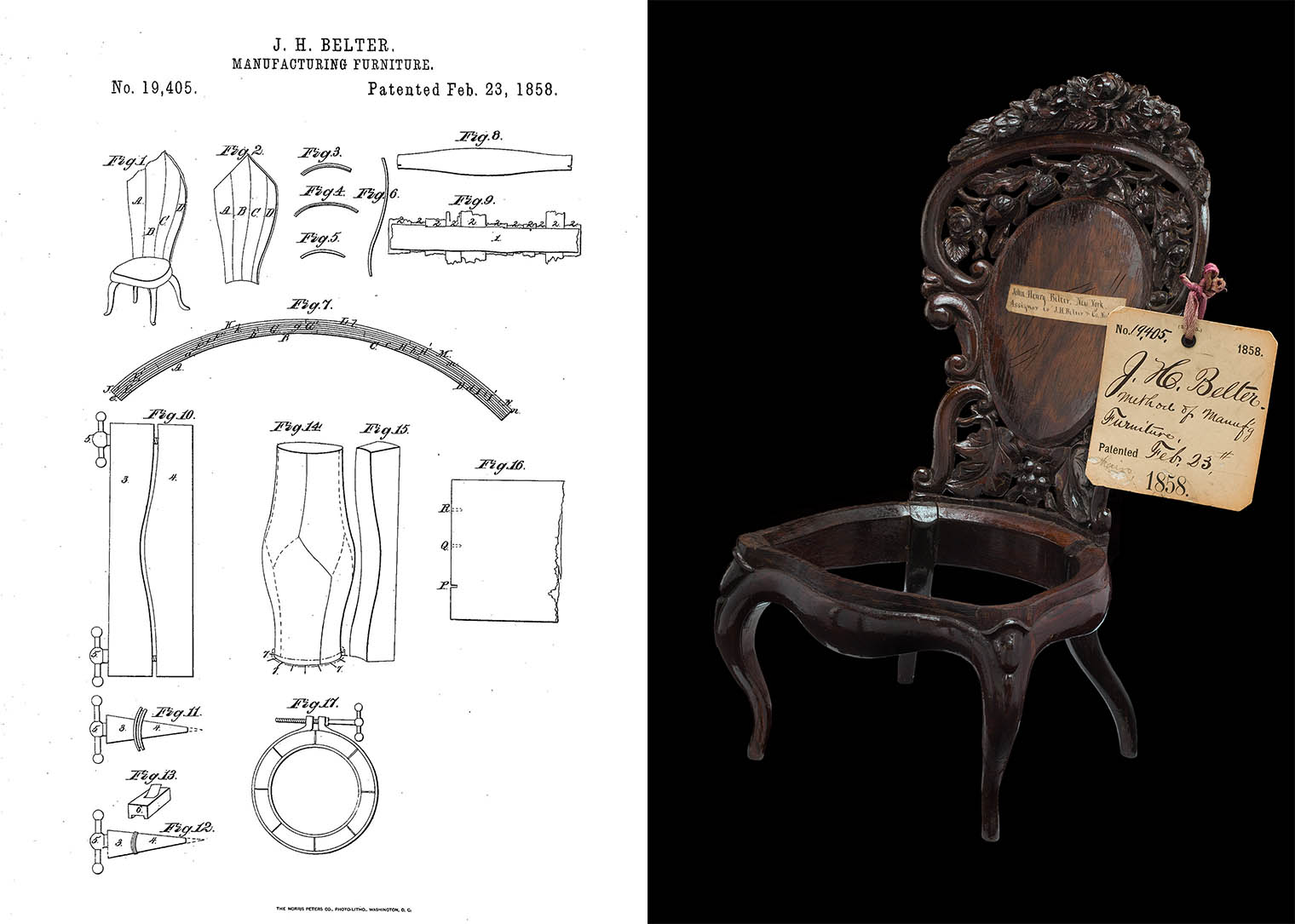

Although early scholarship on Belter erroneously credited him with inventing bent plywood, he did develop innovative techniques for laminating and bending wood and received at least four patents related to furniture making. Of particular interest is US Patent 19,405 issued on February 23, 1858, which describes Belter's process for laminating wood and bending it across two planes to create chair backs. In an advertisement, Belter remarked on the benefits of his "pressed-work," stating "These goods…are much lighter and more graceful, and five hundred percent stronger and more durable than furniture made in the ordinary manner. This work cannot split, crack, or shrink, and is warranted to stand the strongest furnace heat or any climate." By laminating multiple layers of wood with the grain of each layer at right angles, to the adjacent layer, Belter was able to achieve great height, strength, and undulating forms that could be elaborately carved in ways that would have been impossible working with solid wood.

Left: John H. Belter. Improvement in the Method of Manufacturing Furniture. US Patent No. 19,405, issued February 23, 1858. United States Patent Office. Right: John H. Belter. Method of Manufacturing Furniture Patent Model (US 19,405), 1858. American, New York. Wood. Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History (65.0299).

An 1858 R. G. Dun credit report on Belter's operation noted, "They make up the best of furniture. Have a [good] trade, with a [good] Class of customer." Belter's clients are known to include wealthy patrons in New York, as well as other parts of the country ranging from Chicago to Natchez, Mississippi. Documentation surrounding his estate suggests that Belter enjoyed a successful thirty-year career in New York. Following his death in 1863, Belter's business partners, his brothers-in-law J. H, William, and Frederick Springmeyer, continued the business for two more years before changing its name to Springmeyer Brothers. They ultimately closed the operation in 1867.

It is difficult to confidently assign examples of furniture to Belter because they are generally not marked or labeled and little documentation survives. The furniture on view in the Rococo Revival Parlor is attributed to him based on its quality and methods of construction, lamination, and carving.

Donating the Room to the Museum

Sirio Molteni and Rita Molteni Pooler contacted The Met in 1965 shortly before their house was scheduled to be demolished to make way for a high-rise apartment building and offices owned by Goodwill Industries. In consultation with the curatorial staff, Sirio and Rita decided to give the Museum the architectural elements from the double parlors that graced the southern end of the house. With little time remaining before the wrecking ball arrived, a team was dispatched to photograph, measure, and dismantle the parlors. The salvaged architectural elements were then placed in storage, where they remained for almost twenty years. After much restoration of the original architectural elements, the parlor was installed and unveiled to the public in 1983 as part of the newly renovated and expanded American Wing.

Image: Removing the architectural elements of the double parlor from the mansion, 1965. American Wing curatorial files.

Installation at the Museum

Left: Detail of the columnar screen and cornice moldings in situ prior to the mansion's demolition, showing a later paint scheme. American Wing curatorial files. Right: Detail of cornice molding, as installed at The Met.

Originally, the Museum contemplated installing both parlors, each with different style furnishings in each, since the style of the rooms was thought to represent a transition from the Greek Revival to the Rococo Revival style;. Ultimately, the Museum decided to install just one. When the Museum's curators set out to re-create the parlor, a few structural modifications had to be made: the room was slightly widened, a window was removed from one of the long walls, and a chimney breast and carved white marble mantel from an 1853 house in North Attleborough, Massachusetts were added. Photographs taken when the rooms were removed from the house show the parlors without any fireplaces. Because a floor plan drawn in the 1920s indicates fireplaces in the parlors and a typical parlor of the period would have had a fireplace, the curators decided to add one. The presence of floor vents suggests that the house may have depended on central heating from the start, an unusual, technologically advanced feature for the time. To create the intricate plaster cornice, precise molds were made from samples of the original plasterwork, and a new cornice was cast for the room's installation.

Image: Detail of the columnar screen, as installed at The Met.

Analysis of paint colors and finishes

Left: Detail of the parlor door’s framing as installed at The Met. Right: The ceiling medallion in the double parlor in situ prior to the mansion's demolition. American Wing curatorial files.

Detailed micro-chemical analysis of the architectural elements from the Whittemore House was performed to determine what paint colors and finishes were originally used. The analysis revealed that all of the woodwork, including the columns, pilasters, base moldings, door and window frames, and sash were primed with a white lead and linseed oil mixture and finished with a white semi-gloss zinc oxide oil paint. It also indicated that polychromatic schemes were added near the end of the nineteenth century.

Examination of the ceiling medallion revealed that the ornamental plasterwork was originally painted monochromatically with a warm cream calsomine paint, suggesting the entire ceiling was a cream color. The four-panel mahogany door in the left wall of the room was initially treated with a rubbed shellac finish, and its surface was renewed with a second shellac coating. Today, the parlor is finished to reflect its original appearance.

Decorating the Room—Wallpaper, upholstery, curtains, and carpet

In selecting wallpaper, upholstery fabric, curtains, and carpet, Museum curators relied on surviving examples as well as design manuals and publications from the period. The wallpaper in the room is a reproduction of a period damask-patterned paper that has been separated into panels with trompe-l'oeil architectural molding that was pasted over the damask paper. The four "pictures" in trompe-l'oeil frames are wallpaper views of Paris made by the French manufacturer Jules Defosse in 1857. Study of surviving examples of mid-nineteenth-century wall treatments in houses in New York City and Natchez, Mississippi, informed the curators' decisions.

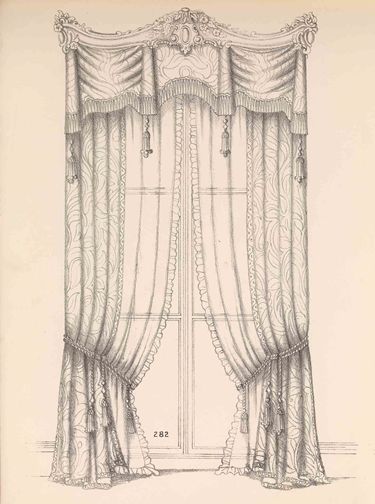

The upholstery fabric used for the draperies and furniture coverings reproduces a blue-and-gold silk lattice-patterned brocatelle found in Camden, a house in Port Royal, Virginia, built in 1856 to 1859 for William Carter Pratt. The draperies' design is based on Plate 282 of The Cabinet of Practical, Useful and Decorative Furniture Designs by Henry Lawford, which though undated, was most likely published during the 1850s. The white lace curtains are copied from examples in the American Wing's collection that date to the mid-nineteenth century and were originally used in Century House, in Cazenovia, New York. Crowning the window treatments are gilt wood and plaster cornices that descended through the family of John Taylor Johnston, who served as the first president of The Metropolitan Museum of Art from 1870 to 1889. Their curvaceous forms and C-scroll ornament suit the Rococo Revival aesthetics of the room.

The highly patterned mid-nineteenth-century machine-woven British carpet is the type of floor covering referred to in the period as a "tapestry velvet." Its jewel-like colors oversized swirling pattern of roses and thistles surrounding Rococo cartouches make it a perfect complement to the curvaceous Belter furniture in the room. It was woven in narrow strips that could be cut to fit the dimensions of any room, though a bold pattern like this would look best in a large scale room. Initially, curators set out to reproduce this carpet; however, none of the samples succeeded in capturing the colors or look of the original. After several attempts at creating a historically accurate reproduction failed, curators decided to use this period carpet from the collection, which they pieced together with another carpet of similar date and style. The carpet arrived at the Museum wrapped in copies of the 1881 New York Evening Post, suggesting it was used in a New York home during the nineteenth century.

Image: Plate 282 in Henry Lawford's, The Cabinet of Practical, Useful, and Decorative Furniture Designs (London, 1855). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Transfer from the Library of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991 (1991.1073.171)

Furnishing the Room in the Rococo Revival Style

View of the Rococo Revival Parlor.

The Whittemore furniture is not known to survive, and no detailed descriptions have been found; however, the furnishings on view in the room are the type and style the family likely would have used in the parlor. When the room was first installed, curators thought the John Henry Belter suite was somewhat grander than the furnishings that originally would have graced the room; however, recent research has shed new light on Horace Whittemore's business activities and wealth, making it reasonable to suppose he could have owned a parlor suite much like the one now displayed in the room.

Rococo Revival style furniture emerged in Europe during the early decades of the nineteenth century as designers and craftsmen began to turn to the recent past for inspiration. Characterized by the revival of curvaceous cabriole legs, C- and S-shaped scrolls, and naturalistic carving, the Rococo Revival style gained popularity in France during the reign of Louis-Philippe (1773–1850; reigned 1830–48). Consequently, the style was frequently called "Modern French." For American patrons seeking to decorate their homes in the latest French taste, Belter furniture represented the height of elegance and luxury.

A small but important detail in the room is the round brass and porcelain knobs on the wall near the mantel. They comprise a bell pull that family members would have used to summon the staff, serving as a reminder of the servants who took care of the house and its occupants.

Image: Alternate view of the Rococo Revival Parlor.

Suite of seating furniture

Attributed to John H. Belter (American, 1804–1863) or J. H. Belter & Co. (1854–65). Armchair and Tête-à-tête. New York, 1850–60. Mahogany, ash, pine, walnut. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Charles Reginald Leonard, in memory of Edgar Welch Leonard, Robert Jarvis Leonard, and Charles Reginald Leonard, 1957 (57.130.2, .7)

Because Whittemore likely owned a set of fashionable seating furniture produced by one of New York's leading cabinetmakers, museum curators selected this impressive suite of rosewood seating furniture in the Rococo Revival style for the room. The assembled suite consists of a sofa, two armchairs, two side chairs, and a distinctive tête-à-tête and exhibits a rich decorative vocabulary of C- and S-curves and scrolls, cabriole legs, delicate piercing, and extravagantly carved floral ornament. Attributed to the firm of John H. Belter, the seating furniture exemplifies the laminated, steam-bent, and ornately carved techniques now synonymous with the firm's proprietor. Although Belter did not invent the process of laminating woods or steam-bending, he did receive a patent in 1858 for improvements to these methods of furniture production.

The carved and pierced asymmetrical crests on the armchairs display a particularly masterful and energetic expression of Rococo taste. On the sofa, leaf-filled cornucopias scroll along the crest rail and connect the central floral bouquet with the two carved floral passages on each side. Although the sofa exhibits slightly less refined carving than that on the other seating forms, the robust gadrooning along the seat rail is also found on the S-curves that frame the upholstered chair backs. Smooth, highly polished passages of uncarved rosewood accentuate the graceful lines of the tête-à-tête ("head to head"), also known as "a confident." The C-curves along the crest rail and stiles stand proud amid flowers, grape bunches, acorns, and other fruits and foliage carved in high relief. This unique French form was well-suited to the parlor as its two chairs facing in opposite directions allowed for discreet conversation. Each object sits on castors, which allowed the furniture to be move about the room to suit the occasion and needs of the owners.

Attributed to John H. Belter (American, born Germany, 1804–1863) or J. H. Belter & Co. (1854–65). Sofa. New York, 1850–60. Rosewood, ash, pine, 48 1/2 x 89 3/4 x 29 1/2 in. (123.2 x 228 x 74.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. Charles Reginald Leonard, in memory of Edgar Welch Leonard, Robert Jarvis Leonard, and Charles Reginald Leonard, 1957 (57.130.1)

Tables

Attributed to John H. Belter (American, born Germany, 1804–1863) or J. H. Belter & Co. (1854–65). Console table and Center table. New York, ca. 1855. Rosewood, marble. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Gloria and Richard Manney, 1980 (1980.510.2, .1)

The center table and pair of console tables on view in the parlor, also attributed to John H. Belter, exemplify his firm's technical virtuosity and exuberant carving. The center table, one of Belter's most elaborate works, is bedecked with abundant garlands of fruits and flowers. Each of its four sinuous legs are composed of two carved dolphins, and the stretchers converge below a lush carved bouquet of roses. The castors at the feet allow for the table to be moved about the room.

The pair of console tables are a tour-de-force of carving. The lace-like aprons and sculptural bouquet at the center of the stretchers exhibit the striking naturalism that Belter's team of carvers was able to achieve in wood. The heavy floral passages at the knees of the cabriole legs are balanced by the piercings throughout the graceful curves. The strength and durability of Belter's furniture, qualities the firm touted in advertisements, manifest in these three graceful table forms that appear to effortlessly bear the weight of heavy, white marble tops.

Mantel

Once the decision was made to incorporate a chimneybreast and mantelpiece into the period room, curators selected this ornately carved white marble mantel and fireplace grate, which came from an Italianate mansion built for Edmund Ira Richards (1816–1882), a prominent jewelry manufacturer, in North Attleborough, Massachusetts. The mantel was originally in the house's parlor, and its use of shell, leaf, scroll, and floral decoration reflects the popularity of the Rococo Revival style in American interiors during the 1850s.

Richards' house descended to his daughter Anna L. Richards Tweedy, and then her son, John Edmund Tweedy. The property was sold and the house demolished following the death of his wife, Maude Fisher Tweedy, in 1962. Additional furnishings from the house's parlor, including a chandelier, two sconces, a pier mirror, and window cornices, are also in the Museum's collection.

Image: Mantelpiece and fireplace grate. North Attleborough, Massachusetts, ca. 1853. Marble, iron, silver, 50 x 74 in. (127 x 188 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Frederick Wildman, 1964 (64.36.1a-c)

Parlor dome

During the nineteenth century, new methods of transport, greater access to books and periodicals, and the establishment of public institutions with natural history collections increased opportunities to learn about the natural world. Museums, botanical gardens, and other scientific exhibitions educated and entertained the general public. The collection of natural specimens, such as ferns, shells, and animals, became a popular pastime during the Victorian era, yet many also found pleasure in reworking or imitating nature while creating new objects for display.

Domestic decor and furnishings, particularly those of the formal parlor, were often used as vehicles for demonstrating one’s taste, sophistication, and understanding of the outside world. Natural objects were commonly integrated into the parlor and displayed under glass domes. Known as parlor domes, these objects could be found on a mantelpiece, center table, étagère, or piano. The displays within these blown glass domes varied enormously, ranging from taxidermy to tableaux crafted from human hair, feathers, shells, wax, and wool. The contents served to prompt enlightened conversation, and the glass provided protection from the deteriorating effects of dust and dirt while highlighting prized possessions.

The glass dome featured in the Rococo Revival Parlor contains an arrangement of woolen birds mounted on moss-covered branches, which achieve a realistic appearance through a variety of carefully rendered details. This would have required the maker to study its subjects with both an artistic and scientific eye. While the contents, materials, and techniques of parlor domes vary significantly, these objects reveal the prevailing interest in the natural world during the second half of the nineteenth century.

Image: Parlor dome. Pennsylvania, ca. 1850-60. Wool, twigs, moss, brass, glass, H. 29 1/2 in. (74.9 cm); Diam. 16 3/4 in. (42.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Friends of the American Wing Fund, 1982 (1982.287a–c)

Chandelier

This chandelier, originally intended for gas and now electrified, was probably made about 1850 by Henry N. Hooper and Company of Boston. The gilt brass arms, chains, and central frame feature rosebuds and other floral motifs that echo those found on the room's furniture. The baluster stem is composed of overlay glass attributed to the Boston and Sandwich Glass Company. Here, the top blue layer has been ground back in a circular pattern to reveal the clear glass underneath. Similar decoration appears on the overlay glass that comprises the stems of the lamp and pair of girandoles also on view in the gallery. The chandelier's etched and cut-glass shades, which are later replacements, would have softened the flickering glow of the gas flame.

Image: Probably designed by Henry N. Hooper and Company, attributed to Boston and Sandwich Glass Company (1825–88). Chandelier. Probably Boston, Massachusetts, ca. 1850. (ca. 1831–68). Glass, brass, 64 1/8 x 34 1/2 in. (162.9 x 87.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1969 (69.170)

Stereoscope

Left: Alexander Beckers (d. 1905). Stereoscope. New York, 1859. Pine, rosewood, glass, 18 3/4 x 10 1/2 x 11 1/4 in. (47.6 x 26.7 x 28.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1969 (69.197) Right: Detail of patent drawing. Alexander Beckers (d. 1905), Apparatus for Exhibiting Stereoscopic-Pictures. US Patent No. 16,962, issued April 7, 1857, Reissue No. 890, issued January 31, 1860. United States Patent Office.

The advent of photography in the nineteenth century brought about a quick succession of technological advances related to capturing, producing, and viewing photographic images. The stereoscope is a device that uses an eyepiece with two separate lenses to view a stereoscopic image, which consists of two slightly different images printed side by side. Viewing them through the lenses, the human brain combines the two images, and the user perceives a single view that simulates three dimensions. The depth created by the stereoscope brought an additional level of realism to photography.

New York daguerreotypist Alexander Beckers (died 1905) created this design for a tabletop stereoscope in 1857 and then, as noted on the small label affixed to the front, incorporated multiple patented improvements. The large quadrangular rosewood structure allowed for multiple stereoscopic slides to be stored in the device. These could then be viewed in succession by turning the knob on the right side of the box.

Parian porcelain

Group of Parian porcelain objects (Left to right: 30.120.159, 47.90.28, 47.90.29, 47.90.37, 30.120.160) on view in the Rococo Revival Parlor.

A selection of molded Parian porcelain objects and figural sculptures decorate the room. Developed in England in the 1840s, Parian is a porcelain body distinguished by a higher proportion of feldspar. When fired at a lower temperature, it takes on the appearance of unpolished marble with an ivory coloring. Less expensive than bronze and more durable than plaster, Parian was often used to bring copies of works of art into the middle-class parlor, exemplified in this installation by the reproduction of Hiram Power's Greek Slave on the console table.

Ornamental vases, boxes, and fancy articles made of Parian were also popular decorations for the parlor by the mid-nineteenth century. On the mantelpiece is a small, covered box ornamented with a putti sleeping against a basket of flowers; a female allegorical figure of Autumn, carrying an abundant basket of grapes; and a covered jar with applied grapes. Positioned on the lower shelf of the pier mirror is an assembled garniture consisting of five vases, shown here, consisting of three polychrome vases with floral decoration and two open-mouth, dolphin-shaped vases. All are thought to have been made in Bennington, Vermont, the location of the first American Parian manufactory.

Image: Manufactured by Minton and Company (1793–present), after Hiram Powers (American, 1805–1873). The Greek Slave. England, 1849. Parian porcelain, H. 14 1/2 in. (36.8 cm); Diam. 4 in. (10.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Russell E. Burke III, 1983 (1983.492)

Keep Learning

American Revival Styles, 1840–76

Read more about American Revival Styles in the nineteenth century in this Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History essay.

American Rococo

Read more about American Rococo in this Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History essay.