Richmond Room

Richmond, Virginia, 1810–11

Matthew Thurlow, Research Associate; Amelia Peck, Marica F. Vilcek Curator of American Decorative Arts; and Moira Gallagher, Research Associate

One of the most visually striking period rooms in the American Wing, the Richmond Room offers a curated suggestion of the grandeur of early-nineteenth-century domestic life for wealthy Americans.

On view in Gallery 728, the room's most notable features—its rich mahogany woodwork and blue-and-gray King of Prussia marble baseboards—were purchased from a house built in 1810–11 for Richmond lawyer William Clayton Williams (1768–1817). The modern wallpaper featuring scenes of Paris is a reproduction of a type sold in the United States in the 1810s. The elegant furniture by Duncan Phyfe (1770–1854) and Charles-Honoré Lannuier (1770–1854) further enhances the sophisticated Anglo-French aesthetic of the room.

An alternate view of the Richmond Room.

Setting

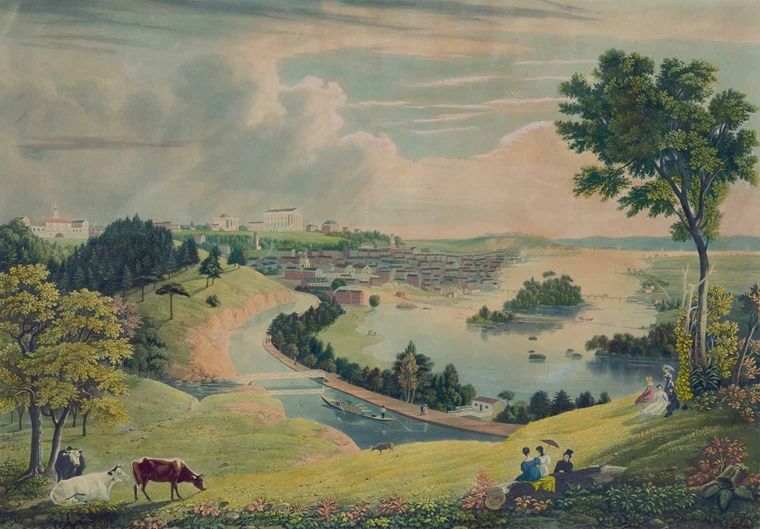

Image: William James Bennett after George Cooke, Richmond, from the Hill above the Waterworks, 1834. Aquatint. The William's House was located on top of the hill behind the Virginia State Capitol. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-pga-03119

When Richmond became the capital of Virginia in 1780, the small town blossomed into a thriving city. It grew from just a few hundred residents to almost twelve thousand by 1820. The city's location at the westernmost navigable point of the James River was key to its growth. Advantageously positioned between Virginia's interior and the coast, Richmond was an important manufacturing center and trading hub, and the processing and export of tobacco was one of its principal industries. Much of the city's economic success was supported by the labor of enslaved individuals, who made up more than one-third of the city's total population by 1820. Working in industrial, agricultural, and domestic settings, these men, women, and children were actively bought and sold as property through the city's port. Richmond would become a major transaction point in the domestic slave trade during the late antebellum era, second only to New Orleans, and the capital of the Confederacy during the Civil War.

Richmond's financial prosperity during the early Federal period and its role as the state capital made it home to an elite class of merchants and professionals, many of whom built grand houses and hired specialized craftsmen to create lavish interiors with decorative woodwork and ornamental plaster ceilings. The Richmond Room comes from the William C. Williams House, which was built between 1810 and 1811 and remained a local landmark until it was razed in 1936.

Landmark home in Virginia's flourishing capital

In 1817, an English visitor to Richmond remarked that the neighborhood in which the Williams House was located was "inhabited by the more opulent merchants, and professional men, who have their offices in the lower town. Their houses are handsome, and elegantly furnished, and their establishments and style of living display much of the refinement of polished society [in Europe]."

One of the most appealing aspects of the Williams House was its location. Positioned on what is now North 8th Street, between Marshall and Clay Streets, it was in a neighborhood known as "Court End," close to the Virginia State Capitol but well removed from the mercantile activities of the city's bustling riverfront. Although the Williams House was demolished, surviving neighborhood houses from around the same period, including the Wickham-Valentine House and the Virginia Governor's Mansion, reflect the wealth and sophistication of the area.

Image: The Governor's Mansion, Richmond, Virginia, ca. 1905. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection. LC-DIG-det-4a12503.

Exterior

The two-story Williams House had a standard five-bay facade, with stone lintels and sills bracketing the windows, and brickwork laid in a fashionable Flemish bond pattern, which alternates the placement of the bricks' headers (short end) and stretchers (long side).

Williams's property extended over two lots, which he had purchased in 1808. In addition to the house, he built several other freestanding buildings on the property, including a small office, a kitchen, a stable, and a smokehouse. Together, these brick buildings were valued at almost $12,000 in 1812.

Image: Conjectural rendering of the front facade of the Williams House, showing the original brickwork, window surrounds, and doorway. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Interior

The overall design of the Williams House is atypical for a Federal-period home. While most early-nineteenth-century dwellings featured a central hall that ran the full depth of the house and included an open staircase, there is evidence that Williams's entryway terminated at an enclosed staircase on the right and a dining room on the left.

The parlor, now installed at The Met, was located off the hall in the front of the house. The two doors that flank the fireplace create symmetry in the room. While the door to the left led to the dining room, the door to the right, now used by Museum visitors to enter the room, was a false door. The paneling and ornamentation throughout the parlor were carved from solid mahogany, an expensive hardwood imported from the Caribbean and Central America.

Image: A plan showing the first floor of the Williams House. Library of Congress, Washington D.C.

Mahogany

Image: J. McGahey, Felling Mahogany, Liverpool, England, ca. 1850. Lithograph, 6” x 9”. Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society

The mahogany tree once shaded vast quantities of rainforest on the Caribbean Islands, as well as the coastal lands along the Bay of Honduras. With the expansion of Spanish and British colonial rule in the region, mahogany became a globally-traded luxury commodity by the eighteenth century. Prized for its rich color and figured grain, it was used to create fine furniture and interior woodwork and it became an outward sign of wealth and good taste. Like many valued natural resources, however, the history and legacy of its extraction is fraught with ethical concerns.

The increased demand from the European and colonial elite led to rampant deforestation and the destruction of unique Caribbean and Central American ecosystems, the effects of which are still visible today. Additionally, the labor of enslaved people was exploited to harvest vast quantities of the majestic tree's wood. Scattered throughout the landscape, the tree would need to be identified, felled, stripped of its branches and leaves, and roughly squared by a cutting crew of enslaved people. The valuable massive tree trunk then needed to be brought to a port from which it could be shipped abroad. This required the same crew to clear a path through the dense terrain in order to transport the tree to the nearest waterway, upon which the logs were floated to the main port. This highly dangerous and grueling manual labor, executed in the hot and humid Caribbean climate, made for inhumane conditions. As resources were depleted near the coast, harvesting moved farther inland and demanded more time, labor, and risk.

The Richmond Room displays an impressive assemblage of mahogany furniture and architectural woodwork created in the United States during the early years of the nineteenth century. Williams made a bold expression of his social status and financial achievement when he selected to use sumptuous mahogany for his drawing room's paneling and doors. Similarly, visitors to the New York residence of Thomas Cornell Pearsall (1768–1820), who originally owned the suite of seating furniture on view in the room, would have been impressed by his mahogany furniture, executed in the latest taste and at great expense.

Changes over time

Left: The front facade of the Williams House, just before its demolition in 1936. The porch, crown moldings above the windows, and bracketed roof were all added by later generations of owners. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Right: The rear of the Williams House during demolition in 1936. The stone lintels above the windows are original to the house. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

In the mid-nineteenth century the stucco surface, shown in this photograph, which obscures the elegantly laid Flemish bond brickwork, was likely applied as part of a renovation. The columned porch, corbelled roof cornice, and crown moldings that project above the windows are features common to the Italianate style popularized at that time.

When the Williams House was dismantled in 1936, historians discovered evidence of a fire that had consumed the second story, attic, and roof at some point in the house's history. Newspaper articles confirm that on July 16, 1864, the upper stories of the residence, then no longer owned by the Williams family, were severely damaged by fire, while the ground floor, where the parlor was located, suffered water damage from the efforts to extinguish the flames. The application of the Italianate ornaments and stucco may have taken place when the upper portion of the house was rebuilt after the fire.

The Williams family

This room's original owner, William Clayton Williams (1768–1817), was a lawyer who moved to Richmond in 1808 to try cases in Virginia's Superior Court. He spent much of his early life in Culpeper, Virginia, before moving to Fredericksburg. In 1794, he married Alice Grymes Burwell (1774–1842), the daughter of Lewis and Judith Page Burwell. The marriage brought together two prominent Virginia families, and the couple had two children who survived to adulthood, Lewis Burwell Williams (1802–1880) and Lucy Page Williams Smith (1808–1888).

After moving to Richmond, Williams became a leading member of the state's Superior Court. He and his distant relative, United States Chief Justice John Marshall (1755–1835), were neighbors and friends. During the War of 1812, Williams served in the Virginia militia as well as on the Richmond Vigilance Committee, responsible for defending the city against a British attack. The 1817 inventory of his estate suggests that the Williams House was sumptuously appointed with stylish furnishings, many made of mahogany, in the Neoclassical style. Williams's taste must have been well-respected as he was appointed to identify, lease, and outfit a temporary residence for the Governor.

Williams's position in society and ability to decorate his house with fine furnishings was facilitated by his role as an enslaver. His obituary, pictured here, praises his professional accomplishments and describes him as a "humane master," a problematic characterization of his role in a system that actively denied the humanity of those it enslaved. During Williams's lifetime, it was expected that a man of his social standing held people in bondage. This was a sign of financial success, since the monetary value assigned to an enslaved person was substantial, but it was also a way to accumulate greater wealth, as Williams's exploitation of enslaved people's labor eliminated the need to pay wages. Records confirm that Williams enslaved at least seventeen individuals at his Richmond residence: Billy, John, George, Willis, Mariah, Carter, Polly, Easter, Mahala, Isabella, Mary, Henry, Sukey, James, and two men who were both named Thom. The family also enslaved at least forty additional individuals, whose names are presently unknown, to cultivate their other land holdings, which included a large agricultural estate of 900 acres and mill in nearby Goochland County.

Image: Obituary for William C. Williams published in the Virginia Patriot on October 21, 1817.

Enslaved in Richmond

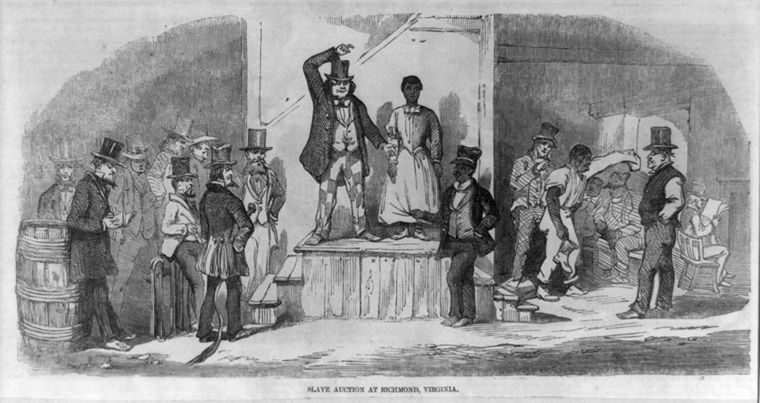

Eyre Crow, "Slave Auction at Richmond, Virginia" published in The Illustrated London News, September 27, 1856. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-15398

Following Williams's death in October of 1817, his widow sold various portions of his estate, including their Goochland County property and the forty enslaved individuals who were forced to labor there. The death of an enslaver signaled great uncertainty for those held in bondage. Efforts to settle the estate frequently resulted in the sale of enslaved people, who were callously viewed as valuable property. In fact, in Williams's 1817 estate inventory, enslaved men George and Billy are assessed at $750 and $600 respectively, the two most valuable entries on the seven-page document.

The sale of the forty individuals enslaved by Williams occurred in January 1818 at Bell Tavern. This tavern, which also hosted offices for slave traders, was located in Richmond's Shockoe Bottom, the commercial section of the city by the docks that housed multiple businesses devoted to the sale and imprisonment of enslaved people. By the 1850s, Richmond was second only to New Orleans as the center of the nation's domestic slave trade, and the cruelty and commodification of human life that played out in its taverns, auction rooms, and prisons led one such establishment, Lumpkin's Jail, to be known as "the Devil's half acre."

Being sold in Richmond likely meant permanent separation from family and community and forcible relocation from the upper South to the lower South, where the grueling cultivation of cotton, sugar cane, and other intensive crops was on the rise during this period. It may have been these pending circumstances that inspired Sam Saunders, a twenty-two-year-old man who was enslaved by Williams, likely at the Goochland County property, to escape his enslavement around the time of Williams's death. He was later captured outside of Richmond.

Later occupants

Williams House when occupied by administrative offices for the Richmond public schools. ca, 1930, Library of Congress, Washington, D,C.

After Williams's death, his widow Alice Williams continued to reside in the house with at least nine enslaved men and women. In the 1820s, she rented rooms to boarders traveling to Richmond for work at the Capitol. In her will, Alice bequeathed these nine enslaved individuals—John, Willis, Isabella, Tom, Columbia, George, Jane, Samuel and Jenny—to her children and grandchildren upon her death in 1842. Her son-in-law John A. Smith later advertised the "spacious and elegant establishment" to Richmond residents in need of lodgings.

The house was subsequently sold out of the family and owned by wealthy professionals and tradesmen such as dentist John G. Wayt, and later the furniture maker, undertaker, and lumber dealer John A. Belvin (1814–1880). Census records confirm that Belvin enslaved at least five individuals, three women and two men, at the North 8th Street mansion. As one of Virginia's leading lumber merchants, Belvin, who frequently marketed mahogany amongst his company's offerings, likely had a keen appreciation of the residence's sumptuous woodwork. These later owners sold off parcels of the original plot, and the Williams House came to be hemmed in by smaller houses.

At the turn of the century, the house was utilized by the Young Men's Hebrew Association, and prior to its demolition in 1936, the Richmond public schools used it as an administration building.

Theophilus Nash (about 1790–1874)

The Williams House was constructed between 1810 and 1811, during a building boom that drew a large number of talented architects, carpenters, ornamental plaster workers, and decorative painters to Richmond. The architect of the Williams House has not been identified; however, Massachusetts-born architect Alexander Parris (1780–1852) is known to have designed contemporaneous houses in the Court End neighborhood, including the Wickham-Valentine House and the Virginia Governor's Mansion. Twenty-year-old Theophilus Nash, one of the craftsmen who worked on the house, carved his named in the top of one of the wooden door frames. Previous scholarship suggested that Nash may have worked as a designer of the Richmond Room, but no corroborating information has come to light. Considering the placement of the signature, he may have worked as a carpenter on the project.

Top: The designs for the anthemia on the door surrounds in the Richmond Room relate to those on plate 43 in William Pain's Practical Builder (1792).

Bottom: Theophilus Nash carved his name into the top of a doorway in the Richmond Room.

Duncan Phyfe (1770–1854) and his clients

John Rubens Smith (American, 1775–1849), The Shop and Warehouse of Duncan Phyfe, 168–172 Fulton Street, New York City. ca. 1816. Watercolor, black ink, and gouache on white laid paper. 15 7/8 x 19 5/8 in. (40.3 x 49.8 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1922 (22.28.1)

Duncan Phyfe operated a prominent New York City cabinetmaking shop between 1792 and 1847. Born in Scotland, Phyfe was trained in his craft after immigrating to the United States in the 1780s. Phyfe's interpretation of the Grecian style dominated New York furniture design in the early nineteenth century, and he was the most sought after manufacturer in the city for much of his career. In addition to supplying furnishings for New York clients, Phyfe sold chairs and tables to wealthy planters and merchants in the American South and the Caribbean.

One of Phyfe's New York clients was the wealthy merchant and ship owner Thomas Cornell Pearsall (1768–1820). The seating furniture on view in the Richmond Room is attributed to Phyfe and once furnished Pearsall's Manhattan residence, known as Belmont, located along the East River at what is now 58th Street. The specific nature of the firm's trade was varied, and the firm had business relationships in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, England, and Madeira.

Charles-Honoré Lannuier (1779–1819) and his clients

Born in France and trained as a cabinetmaker in Paris, Charles-Honoré Lannuier immigrated to New York City in 1803. Although his career there lasted a mere sixteen years, Lannuier was a leading figure in the development of a distinctive and highly refined style of furniture in the French Neoclassical taste. A contemporary of the renowned cabinetmaker Duncan Phyfe, Lannuier made fashionable gilded card tables, marble-topped pier tables, bedsteads, and seating furniture for wealthy clients numbering among the mercantile and social elite of New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Richmond, and Savannah. William C. Williams's neighbor John Wickham owned a pair of card tables by Lannuier similar to those on view in the Richmond Room.

The two card tables in the room were commissioned by William Bayard (1761–1826), a founding member of the mercantile firm LeRoy, Bayard & McEvers, which actively traded a variety of goods as part of the triangle trade with Europe, the West Indies, and South America. Bayard amassed an impressive fortune and commissioned the tables from Lannuier as wedding gifts for his daughter Harriet, who in 1817 married Stephen Van Rensselaer IV. Van Rensselaer was a wealthy landowner from a storied New York family, and later inherited the large Albany estate Rensselaerswyck. Such a prestigious marriage and impressive gift signaled Bayard's success and progressive tastes to his social peers.

Image: The trade label that Lannuier used between 1812 and his death in 1819.

A rare survivor

The Metropolitan Museum acquired the Richmond Room prior to a large-scale renovation of the American Wing in the 1970s. Much of the woodwork was intact, as was the baseboard of blue-and-gray King of Prussia marble from Pennsylvania. The marble mantel, plaster ceiling medallion, and extravagant wallpaper are not original to the Williams House but suggest elements found in elite Virginia homes of the period. The rich interior is meant to provide an exceptional setting for the Museum's strong collection of early-nineteenth-century decorative arts, rather than being an authentic record of how the Williams family actually furnished the room. Research has shown that while they had rich mahogany furniture and other luxury goods in their home, their taste was likely somewhat simpler than the way this room was decorated in 1980 by curator Berry B. Tracy (1933–1984), a renowned expert in American Classical furniture.

Image: The Richmond Room as first installed in 1980.

Acquiring the Richmond Room

The Richmond Room owes its survival to Thomas Waterman, an architect who helped document the Williams House before it was razed in 1936. Waterman managed to salvage the mahogany architectural elements from the drawing room. He then sold them to York, Pennsylvania, antiques dealer Joe Kindig Jr. It was Kindig who presented the woodwork to The Met in 1968, after it had sat in storage in a barn for more than thirty years.

Berry B. Tracy, the curator who accepted Kindig's gift, described the room as "a revelation to the creative taste and genius of the craftsmen of the Federal Period in America" and expected that it would "be for time immemorial a feature attraction" in the American Wing.

Image: Curator of American Decorative Arts Berry B. Tracy, who oversaw the acquisition and installation of the Richmond Room.

On exhibit

Left: Doorway in the Williams House parlor stripped of its carved ornament, ca. 1936; Right: Door surround when acquired by the Museum. Discolorations indicate the location and design of the missing carvings. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Although the Richmond Room was largely intact when acquired by The Met, it was missing a few of its original decorative details, including the mantel and many of the applied carvings on the door surrounds. Photographs of the Williams House during demolition suggest that these elements were removed prior to 1936. To replace some of the missing carvings, the Museum made plaster casts of surviving components and substituted an Italian marble mantel from a New York town house built in the late 1820s. Curators believe that the original mantel was probably made of King of Prussia marble to match the baseboard.

Final touches

Once the room was installed, the Museum complemented the refurbished mahogany woodwork with ornamental plasterwork and reproduction wallpaper. The graceful plaster ceiling medallion is based on one found at Hampstead, a house built in New Kent County, Virginia, around 1825. The vibrant wallpaper, entitled Les Monuments de Paris, is a silk-screened reproduction of a French wall covering produced by Dufour et Leroy in 1814 and subsequently sold in the United States.

Originally, each color would have been hand printed from hundreds of carved wood blocks, as seen in the fragment of Dufour et Leroy's wallpaper entitled Young Girls Dancing before a Grotto (ca. 1820). The bright colors and solid ink of the modern silk-screened paper has a quite different effect than actual hand-blocked paper, in which the colors are subtler and the ink has a more transparent quality, showing the outlines of the woodblocks, and how the ink was dispersed by the pressure of the blocks being placed on the paper.

Top: Detail of reproduction wallpaper in the Richmond Room.

Bottom:Detail of a hand-blocked wallpaper, House of Dufour, Young Girls Dancing before a Grotto, ca. 1820. Woodblock-printed paper. 74 x 80 3/4 in. (188 x 205.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Friends of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts Gifts, 1993 (1993.297)

American furniture, European elegance

Most of the furnishings in this room were made in New York City. Although Richmond supported a vibrant cabinetmaking community in the early nineteenth century, wealthy Southerners regularly imported furniture from New York City. Cabinetmakers in New York also supplied their Richmond counterparts with wood, hardware, and carved elements.

The design sources of the furnishings extended even farther afield. Following the American Revolution and the War of 1812, Americans sought to distance themselves from the aesthetic tastes of their British foes and became strongly influenced by the French taste for antique-style decorative arts. Many furnishings featured ornamental motifs from ancient Greece and Rome, which were held as cultural models for the newly formed American republic. The excavation of classical sites, the dissemination of pattern books and design treatises, and the immigration of highly trained French craftsmen to the United States fueled the nation's preference for this style of French Neoclassicism.

Suite of twelve chairs, sofa, and two footstools

Left: Side chair, attributed to Duncan Phyfe (Scottish 1768/1770–1854), 1791–1818. Mahogany, brass. 32 1/2 x 17 7/8 x 16 1/4 in. (82.6 x 45.4 x 41.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of C. Ruxton Love Jr., 1960 (60.4.4); Center: Sofa, attributed to Duncan Phyfe (Scottish 1768/1770–1854), ca. 1810–20. Mahogany, tulip poplar, cane, gilded brass. 34 x 84 3/4 x 23 3/4 in. (86.4 x 215.3 x 60.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of C. Ruxton Love Jr., 1960 (60.4.1); Armchair, attributed to Duncan Phyfe (Scottish 1768/1770–1854), 1791–1818. Primary: mahogany; Secondary: cherry (medial braces), ash or oak (stubb tenon feet). 32 7/8 x 21 1/2 x 24 3/4 in. (83.5 x 54.6 x 62.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of C. Ruxton Love Jr., 1960 (60.4.2)

This large suite of furniture, including a sofa, a pair of armchairs, ten side chairs, and a pair of footstools, was once owned by Thomas Cornell Pearsall (1768–1820), a wealthy New York merchant and shipowner. The attribution to the famed furniture maker Duncan Phyfe is based on a Pearsall family tradition and is recorded in an inscription stamped on the inside of the seat rails of the sofa and several chairs. Pearsall's chandelier and sconces are on view in the nearby Baltimore Dining Room.

The curule shape of the legs of the sofa and chairs—also called a Grecian cross frame—is based on an ancient Roman magistrate's folding chair. Formed by two intersecting S-curves, the curule appeared in many early-nineteenth-century design sources and price books, which were the published guides establishing how much a journeyman cabinetmaker was paid to produce a particular piece of furniture.

Pier table

This pier table exemplifies the elegance and quality of furniture produced in Charles-Honoré Lannuier's New York workshop, The gilded swan supports and vert antique dolphin feet illustrate the variety of surface finishes used in the Greek Revival period. The cast-brass ornament attached to the front rail depicts Apollo, the Greek god of truth and light, seated in a chariot drawn by moths. Despite Lannuier's close connection to French designers, the mount was most likely made in Birmingham, England, which was an important center for the production of decorative hardware in the early nineteenth century.

This pier table exemplifies the elegance and quality of furniture produced in Charles-Honoré Lannuier's New York workshop, The gilded swan supports and vert antique dolphin feet illustrate the variety of surface finishes used in the Greek Revival period. The cast-brass ornament attached to the front rail depicts Apollo, the Greek god of truth and light, seated in a chariot drawn by moths. Despite Lannuier's close connection to French designers, the mount was most likely made in Birmingham, England, which was an important center for the production of decorative hardware in the early nineteenth century.

This gilded figural pier table bears the remnants of a trade label Lannuier used between 1812 and his death in 1819. The label is considered to be among the most elegantly designed in American furniture. The engraved text is framed within an image of a cheval glass, or dressing mirror. Using both English and French text, Lannuier identified himself as a cabinetmaker from Paris and signaled to his clients that his work followed the latest fashions from France.

Image: Charles-Honoré Lannuier (French 1779–1819) Pier table, 1815–19. Rosewood, mahogany, marble, gilded gesso, gilded brass, vert antique, with white pine, yellow poplar, maple, ash, mahogany, beech. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Museum Purchase, 1968 (68.43)

Card tables

This superlative pair of card tables is documented to the workshop of New York's resident French ébéniste of the Federal period, Charles-Honoré Lannuier. The tables are remarkable not only for their exquisite beauty but also because they are signed and dated masterpieces descended in the family of their original owner, Stephen Van Rensselaer IV of Albany.

Commissioned by the New York City merchant William Bayard, the tables were part of a larger purchase that included a nearly identical pair of card tables and two pier tables with gilded swan supports, wedding gifts for his daughters Harriet and Maria, who in 1817 married Stephen Van Rensselaer IV and Duncan Pearsall Campbell, respectively. The invoice for the Campbell pieces survives, revealing the high cost of furniture from Lannuier's Broad Street shop. The pair of card tables was priced at $250 and the pier table at $300—astonishing sums at a time when a journeyman cabinetmaker's wage was only about a dollar a day.

Image: Charles-Honoré Lannuier. Card table. New York City, 1817. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Justine VR Milliken, 1995 (1995.377.1)

Pair of window stools

The influence of contemporary English designs on American furniture is evident in the intersecting S-shaped leg supports on this pair of stools. The curule, or Grecian cross frame, design is reminiscent of the suite of seating furniture also on display in the Richmond Room, which was likely manufactured in the workshop of Duncan Phyfe, New York City's leading cabinetmaker.

Image: Window stool, New York City, 1810–20. Mahogany, gilded brass. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, in memory of Berry B. Tracy, and The Richard Hampton Jenrette Foundation, Inc., Mr. and Mrs. Anthony L. Geller and The Equitable Gifts, 1988 (1988.83.1-2)

Kettle stand

Kettle stands are a rare form of American furniture. They typically take the shape of a worktable but with a marble top instead of wood. Marble better withstands the heat of a hot-water urn or coffeepot.

Image: Attributed to the workshop of Duncan Phyfe (American 1765–1854), Kettle stand, 1810–20. Mahogany, marble with yellow poplar, white pine. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Paul Peralta Ramos Gift, 1960 (60.13)

Hot-water urn

Urns were filled with hot water for the preparation of tea or coffee. In 1788, Ann Warder of Philadelphia recorded a diary entry about the purchase of a new silver hot-water urn. She wrote that "our new urn [is] a piece of furniture much admired and for this country particularly convenient, coffee being mostly used." Such vessels had pride of place in the elegant parlors of wealthy Americans during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Image: Stephen Richard (active ca. 1796–1843). Hot-water urn, 1812. Silver. The Metropolitan Museum ofArt, New York. Lent by Private Collection (L.2000.28)

Epergne

An epergne is a table centerpiece for the display of fruit, sweets, or flowers. This example was part of a set that also included a pair of matching candelabra. The original owner was Elizabeth Schuyler, the widow of Alexander Hamilton, the United States' first Secretary of the Treasury.

Image: Epergne. Paris, ca. 1810 Gilt bronze. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1954 (54.172.3)

Chandelier with pair of sconces

Only the wealthiest Americans had elaborate chandeliers and sconces in their homes. These lighting devices were not only expensive to purchase and import from Europe but also required regular maintenance and cleaning—tasks usually allocated to domestic servants. At Williams's Richmond residence, such work would have been carried out by an enslaved person. The Philadelphia merchant George Harrison (1762–1845) acquired this chandelier and matching sconces for his house at 156 Chestnut Street, perhaps while visiting New York, where he obtained a pair of caryatid card tables similar to those by Charles-Honoré Lannuier on view in this room.

Image: Chandelier with pair of sconces. England, 1810–20. Cut glass, gilt bronze. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1934 (34.75.1-.3)

Mantel clock

This Parisian mantel clock suggests the American interest in French luxury goods. The central column supports a gilt figure of Urania, the muse of Astronomy and is flanked by black marble obelisks, each topped by a gilt cockerel.

Image: Mantel clock. Paris, 1800–1830. Slack marble, ormolu, gilt bronze and/or brass, enamel dial, and clock mechanism. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2009.147)

Girandole

A girandole, or girandole mirror, is a piece of convex silvered glass fitted with a circular gilded frame. The convex shape and gilded surface increase the throw of light from the candles placed in the branches.

Image: Girandole. United States or England, 1810-20. Gilded gesso. vert antique with pine. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1921 (21.44.2)

Woven rug

This rug is of a type known as Aubusson, which refers to the town in central France that produced flatwoven tapestry carpets from the sixteenth through the nineteenth century.

Image: Woven rug. France. ca. 1800. Wool. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Frederic R. King, 1952 (52.59)

Mantel

Mantel. Italy, ca. 1825–30. Marble. 52 1/2 x 68 3/16 x 9 7/8 in. (133.4 x 173.2 x 25.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, 1977 (1999.126)

Mantel. Italy, ca. 1825–30. Marble. 52 1/2 x 68 3/16 x 9 7/8 in. (133.4 x 173.2 x 25.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, 1977 (1999.126)

This Italian mantel has a long provenance in New York City. It may have been originally ordered for a house in La Grange Terrace (built 1831–33) on Lafayette Street and was later moved to the Abram Hewitt House at 9 Lexington Avenue (built 1848). The carved tablet at the center of the mantel shows the Greek hero and Roman god Hercules at rest. Beside him are his attributes, a lion skin and the club.

Keep Learning

American Federal-Era Period Rooms

Read more about the Richmond Room and other American Federal Era Period Rooms in the American Wing in this Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History essay.

Duncan Phyfe (1770–1854) and Charles-Honoré Lannuier (1779–1819)

Read more about the furniture making of Duncan Phyfe and Charles-Honoré Lannuier, whose work is on display in the Richmond Room, in this Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History essay.