Van Rensselaer Hall

Albany, New York, 1765–68

Cynthia V. A. Schaffner, Research Associate

This large entrance hall, installed in Gallery 752, was originally part of an impressive Georgian mansion built by Stephen Van Rensselaer II (1742–1769) and his wife, Catharine Livingston Van Rensselaer (1745–1810). Constructed between 1765 and 1768, the house was situated on bluffs overlooking the Hudson River. It served as the manor house for the vast patroonship of Rensselaerswyck, which consisted of almost one million acres and encompassed parts of present-day Albany and Rensselaer Counties

The Van Rensselaer Hall was one of the largest and most elaborate rooms built in prerevolutionary America. The rare hand-painted English wallpaper and the magnificently carved woodwork create an elegant American Wing gallery.

An alternate view of Van Rensselaer Hall, showing its ornate wallpaper

The patroonship of Rensselaerswyck

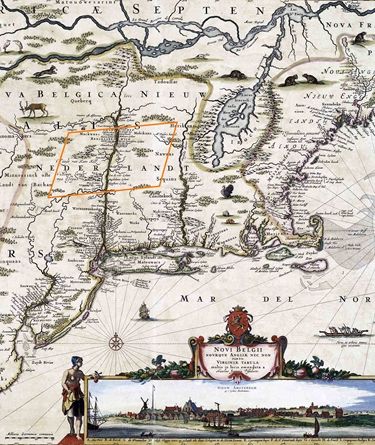

The manor house was built on property originally granted to the Dutch-born Kiliaen Van Rensselaer (1586–1643). A wealthy Amsterdam dealer in jewels and precious stones, Van Rensselaer was a member of the privately owned Dutch West India Company. He was an advocate for setting up private plantations, or patroonships, as a method of settling seventeenth-century New Netherland, which included parts of Delaware, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania. Each patroon was expected to transport fifty adult settlers to New Netherland within four years of being awarded his grant. The patroon had administrative, executive, and judicial rights over the land grant and passed on leadership of the patroonship to his descendants.

In 1629 Van Rensselaer received a land grant for a patroonship located along the Hudson River, about 135 miles north of New York City. Rensselaerswyck, as it became known, was the largest grant issued by the Dutch West India Company and the sole patroonship to remain intact after the period of Dutch colonial rule, which ended in 1664. The estate not only stayed in the family for over two centuries but also grew significantly with purchases and patent grants added by Kiliaen Van Rensselaer's descendants.

Image: The Amsterdam cartographer Claes Janszoon Visscher first issued this map of New Netherland in 1650–51. By 1685 Rensselaerswyck, outlined in orange, had become a vast agricultural colony comprising almost one million acres. New York Public Library

Home to three generations, 1768–1875

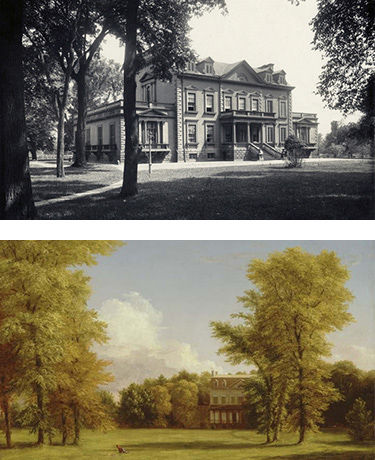

Three generations of Van Rensselaers resided in the manor house built by Stephen II and Catharine Van Rensselaer. Although no surviving images show the original 1768 appearance of the home, it was probably a seven-bay, two-story, Georgian-style brick mansion with small dormer windows piercing a gently hipped roof. The entrance hall retains the woodwork from this first period.

Stephen Van Rensselaer II's heirs altered many aspects of the house over the course of the next century. In 1818 and 1819 Stephen Van Rensselaer III hired the Albany architect Philip Hooker to create two new single-story wings as well as a piazza on the garden front. In the early 1840s Stephen Van Rensselaer IV commissioned further alterations from the noted New York architect Richard Upjohn. After this renovation, Andrew Jackson Downing, the period’s most influential architectural critic, declared that the Van Rensselaer house possessed "perhaps the finest facade of a private residence in America."

Top: This late-nineteenth-century photograph of the front of the Van Rensselaer manor house clearly shows the side wings designed by Philip Hooker around 1818.

Bottom: Thomas Cole. The Van Rensselaer Manor House, 1841. Oil on canvas. Albany Institute of History and Art, Bequest of Miss Katherine E. Turnbull, granddaughter of Stephen Van Rensselaer III (1930.7.2)

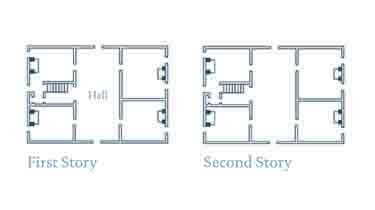

Interior layout

The original layout of the Van Rensselaer manor house was a typical American adaptation of an English Georgian-style interior. Ascending a staircase to the front door, visitors entered directly into the large entrance hall. Measuring 23½ by nearly 47 feet, it extended straight through the house to the back door. Four rooms opened off the hall. A beautifully carved archway led to a narrower side hall, where a staircase led to the second story. This second floor mirrored the first, with four bedchambers opening off a long hallway.

Image: Floor plan of Stephen Van Rensselaer II manor house.

Fashionable wallpaper

Left: The Kirtlington Dining Room (Gallery 511) is another example of the fashionable Rococo style. Right: The Print Room from the Irish Castletown Estate in County Kildare. Image courtesy of: Castletown House, National Monuments Service, Office of Public Works

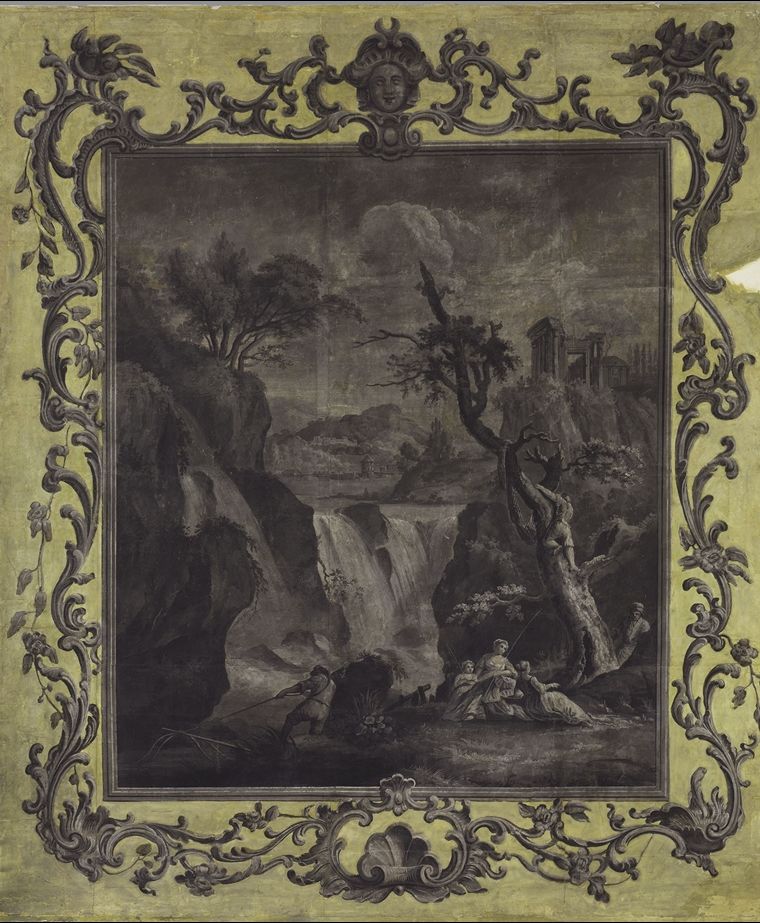

Much of the grandeur and richness of Van Rensselaer Hall comes from the hand-painted English wallpaper that decorates the entire room. The design of the wallpaper was inspired by two styles of decorative work found on the walls of mid-eighteenth-century British interiors: oil paintings framed with Rococo stucco decoration and so-called print-room decoration.

The Museum's Kirtlington Park Dining Room (Gallery 511) from Oxfordshire, England, displays large genre scenes and a pastoral landscape, each individually framed by exuberant raised plasterwork exhibiting Rococo motifs. The Van Rensselaer wallpaper’s other inspiration was the tradition of decorating rooms with rows of fine prints pasted directly on plain-colored walls and framed with printed Rococo borders.

The 1760s witnessed a dramatic increase in the use of imported hand-painted English and French wallpapers in fashionable American homes. The grisaille (shades of gray) color scheme seen in the Van Rensselaer Hall was meant to imitate the prints from which the scenic panels and the panels of the four seasons were copied. Only two other examples of grisaille painted scenic wallpaper are known: one at Harrington House in Gloucestershire, England, and the other in the Jeremiah Lee Mansion, built in 1768, in Marblehead, Massachusetts.

Only two other examples of this grisaille painted scenic wallpaper are known, one at Harrington House in Gloucestershire, England, and the other in the Jeremiah Lee Mansion built in 1768, in Marblehead, Massachusetts. Left: Van Rensselaer Hall, Right: The Jeremiah Lee Mansion, Marblehead, Massachusetts. Marblehead Museum. Photograph by Rick Ashley.

London source

The London-based "paper stainer" who created the magnificent wallpaper in Van Rensselaer Hall remains anonymous. What is known is that Catharine and Stephen Van Rensselaer II commissioned the paper in 1766 through the London merchants Neate and Pigou of Saint Mary's Hill.

The London-based "paper stainer" who created the magnificent wallpaper in Van Rensselaer Hall remains anonymous. What is known is that Catharine and Stephen Van Rensselaer II commissioned the paper in 1766 through the London merchants Neate and Pigou of Saint Mary's Hill.

Painted entirely by hand in tempera on rectangular sheets of medium-weight rag paper, the designs encompass a broad range of blacks and grays with white highlights on an ocher background. All of the designs were made to specifically fit the layout of the Van Rensselaers' room; a guide for placement accompanied delivery of the wallpaper.

Left: The manufacturers of the wallpaper labeled a plan of Van Rensselaer Hall with a letter key for each scene so that workers could hang each piece of wallpaper in its proper place. American Wing Files, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

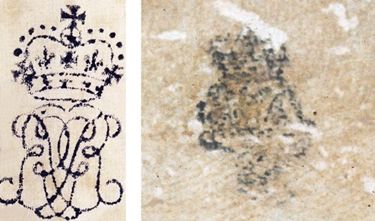

Right: The reverse of many sheets of the Van Rensselaer Room wallpaper were marked with English tax stamps.

Architectural carving

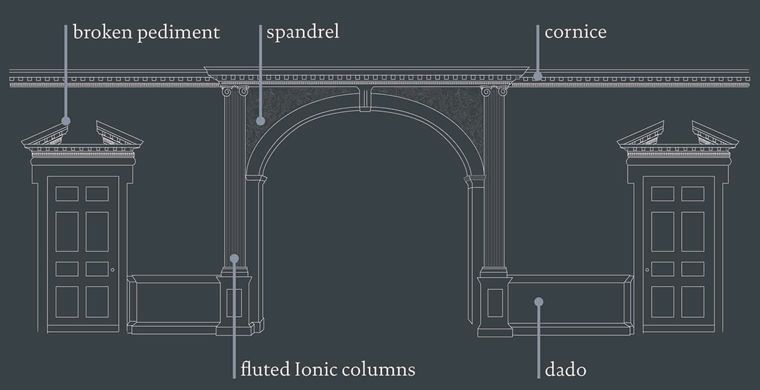

Rendering and diagram of the architectural features in the Van Rensselaer Hall

Van Rensselaer Hall features some of the most splendid Rococo woodwork produced in New York during the 1760s. The design follows the Ionic order, as seen in the elliptical archway flanked by fluted Ionic pilasters. In total, the room features six doorways with broken pediments and four recessed, paneled windows. The hand-painted wallpaper hangs between the dado, at the bottom of the wall, and the cornice, at the ceiling.

The carved spandrels of the archway, with their scrolled foliage, pierced shells, leaves, and blossoms, were copied directly from an engraving in a British pattern book by M. Lock and H. Copland entitled A New Book of Ornaments, with Twelve Leaves. First published in 1752, it was reissued in 1768, when the manor was under construction.

A father-in-law's advice

The original architect of Catharine and Stephen Van Rensselaer II's house is unknown, but Catharine’s father, the merchant and statesman Philip Livingston (1716–1778), certainly played a role in its decoration. In 1768 Livingston served as the intermediary agent who oversaw the shipment of the wallpaper from London to Albany.

The original architect of Catharine and Stephen Van Rensselaer II's house is unknown, but Catharine’s father, the merchant and statesman Philip Livingston (1716–1778), certainly played a role in its decoration. In 1768 Livingston served as the intermediary agent who oversaw the shipment of the wallpaper from London to Albany.

In a letter accompanying the delivery, Livingston gave instructions for the wallpaper's installation, as well as advice on ornamenting the ceilings. "I am told You Intend to get Stucco work on the Ceiling of Your Hall which I would not advise You to do," he wrote. "A Plain Ceiling is now Esteemed the most Genteel."

Image: Pompeo Girolamo Batoni, Italian, Portrait of Philip Livingston, 1783, oil on canvas. Purchased with funds from the Marriner S. Eccles Foundation for the Marriner S. Eccles Masterwork Collection, assisted by Emma Eccles Jones, and a gift by exchange of A. Aladar Marberger and Marilyn Cole Fischbach, from the Permanent Collection of the Utah Museum of Fine Art. UMFA1991.045.001

Building the house

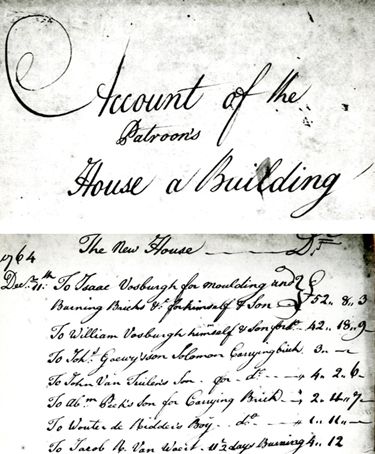

A surviving Van Rensselaer account book provides insight into the construction of the manor house. An entry dated May 13, 1765, records the laying of the foundation. Subsequent entries describe the felling of local trees and their transformation into boards at a sawmill on the property. An on-site kiln produced bricks for the home. In addition, the stones were sourced from quarries south of Albany.

The account book lists purchases of lime, lath, nails, and shingles and records the names of tradesmen who worked on the house. For example, Robert Sharf cemented and set the imported marble mantels in September 1766. Large bricks on the exterior of the home bear the initials of Luykas Hoogkerk, a brickmaker whose name appears repeatedly throughout the account book.

Image: Title page of the account book and entry for December 11, 1764, listing the names of craftsmen

Three manor houses

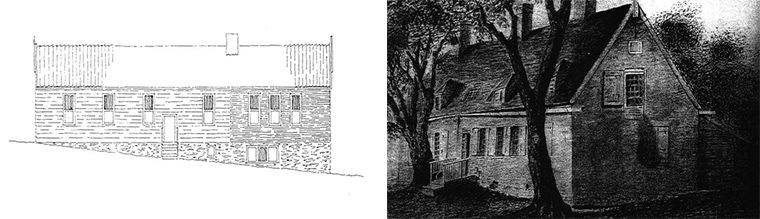

Left: A conjectural rendering of the first manor house, ca. 1659. From Janny Venema, Beverwijck: A Dutch Village on the American Frontier, 1652–1664 (2003); Right: Photograph of a sketch of "Watervliet," the second Van Rensselaer manor house. Francis Pruyn's sketch, ca. 1838. Photograph by Augustus Pruyn, 1880–1900.

Prior to the construction of Stephan Van Rensselaer II's home from 1765 through 1768, the family had built two earlier manor houses on the west bank of the Hudson River in today’s Rensselaer County. The first manor house was built in 1651 by Jan Baptist (1629–1678) and Jeremias (1632–1674) Van Rensselaer, sons of the first patroon.

A flood destroyed that house, so the Van Rensselaer family built a new one on higher ground in 1668. Known as "Watervliet," it served as the manor house until Stephen Van Rensselaer II built his grand Georgian home from 1765 through 1768. "Watervliet" was razed in 1839, and Stephen Van Rensselaer II’s home was dismantled in 1893.

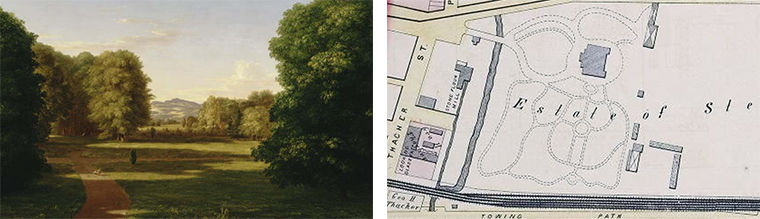

Taming the woods

Left: Thomas Cole (1801–1848). Gardens of the Van Rensselaer Manor House, 1840. Oil on canvas. Albany Institute of History and Art, Bequest of Miss Katherine E. Turnbull, granddaughter of Stephen Van Rensselaer III (1930.7.1); Right: Detail of a map of Albany showing the Van Rensselaer manor house and its associated roads and pathways. From G. M. Hopkins's City Atlas of Albany, New York. (Philadelphia, 1876)

In his book A Description of New Netherland (1655), Adriaen van der Donck (1618–1655), Rensselaerswyck's first schout—or prosecuting officer and sheriff—provided a richly detailed portrait of the region's resources. Dense woods of seventy-foot-tall oak trees sheltered deer, black bears, eagles, turkeys, quail, woodcocks, pheasants, and water snipes. Edible native plants included mulberries, plums, wild cherries, juniper, apples, hazelnuts, black currants, gooseberries, strawberries, blueberries, raspberries, ramps, and wild onions. Medicinal herbs were also plentiful.

By the nineteenth century, the land around the manor house was no longer wilderness, having been cleared and extensively cultivated. In 1840 Thomas Cole painted the manor's gardens, which were considered among the most beautiful in the United States. Period sources record that the gardens included high box hedges, a summer house, and a waterfall that plunged into a gentle stream.

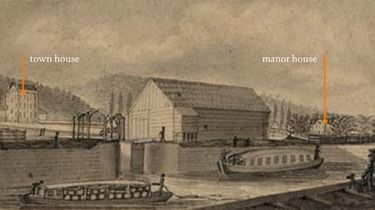

The end of an era

Rensselaerswyck was America's most successful and long-lasting patroonship, surviving both Dutch and British colonial rule. Members of the Van Rensselaer family shaped the history of New York State, serving as state legislators, congressmen, and lieutenant governors. In the nineteenth century, however, the traditional patroonship was challenged. Following a tenants' revolt in upstate New York during the 1840s, the family relinquished the feudal rights to most of its land holdings. By the 1890s the manor house was surrounded by the commercial bustle of the Erie Canal—which in 1825 opened to link the Hudson River at Albany with Lake Erie in Buffalo—as well as a series of railways, and the growing industrial city of Albany. The family moved away from the manor house, and it was dismantled in 1893.

Rensselaerswyck was America's most successful and long-lasting patroonship, surviving both Dutch and British colonial rule. Members of the Van Rensselaer family shaped the history of New York State, serving as state legislators, congressmen, and lieutenant governors. In the nineteenth century, however, the traditional patroonship was challenged. Following a tenants' revolt in upstate New York during the 1840s, the family relinquished the feudal rights to most of its land holdings. By the 1890s the manor house was surrounded by the commercial bustle of the Erie Canal—which in 1825 opened to link the Hudson River at Albany with Lake Erie in Buffalo—as well as a series of railways, and the growing industrial city of Albany. The family moved away from the manor house, and it was dismantled in 1893.

This watercolor, Entrance of the Canal into the Hudson at Albany (1823), brings together key elements from the Van Rensselaer family's history. The Erie Canal is in the foreground, the manor house is at the far right, and the back facade of Harriet and Stephen Van Rensselaer IV's Albany town house can be seen at the far left.

Image: James Eights, Entrance of the Canal into the Hudson at Albany, 1823. Watercolor. Albany Institute of History and Art, Gift of James Eight, 1836

Kiliaen Van Rensselaer

Kiliaen Van Rensselaer (1586–1643) was the original patroon of Rensselaerswyck, securing a land grant in 1629. He was married twice, first to Hillegond van Bijler in 1616 and, after she died, to Anna van Wely in 1627. The father of eleven children, three by his first wife and eight (four boys and four girls) by his second, he was a tenacious businessman and maintained firm control of his large family-owned trading house.

Kiliaen Van Rensselaer never came to Rensselaerswyck, choosing to remain in Amsterdam. Instead, he appointed agents to move to the colony, where they collected annual fees from the tenants, administered justice, and kept him informed through continuous correspondence.

Image: Wedding ring of Anna Van Wely, who married Kiliaen Van Rensselaer on December 14, 1627 New-York Historical Society

Jan Baptist and Jeremias Van Rensselaer

Kiliaen Van Rensselaer invested much of the family fortune in the development of Rensselaerswyck, but it was his sons Jan Baptist (1629–1678) and Jeremias (1632–1674) who actually journeyed to America and took charge of the land. Jan Baptist served as director of the estate from 1651 until the fall of 1658, when he returned to Amsterdam to oversee the family's trading interests.

Kiliaen Van Rensselaer invested much of the family fortune in the development of Rensselaerswyck, but it was his sons Jan Baptist (1629–1678) and Jeremias (1632–1674) who actually journeyed to America and took charge of the land. Jan Baptist served as director of the estate from 1651 until the fall of 1658, when he returned to Amsterdam to oversee the family's trading interests.

Jeremias joined his brother in Rensselaerswyck in September 1654 and was the first member of the family to establish himself permanently in America. He generated a voluminous collection of correspondence and also wrote a chronicle of his experiences in America. He married Maria Van Cortlandt on July 12, 1662, and together they had five children. It was Jeremias who built the second manor house in 1668.

Image: In 1656 Jan Baptist Van Rensselaer gave this stained-glass window to the First Dutch Reformed Protestant Church of Beverwyck, New York. The Van Rensselaer coat of arms appears in the center of the composition. The window was later installed in the Van Rensselaer manor house and is now on view in the New York Dutch Room (Gallery 712) on the third floor of the American Wing. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Mrs. J. Insley Blair, 1951 (52.77.46)

Stephen Van Rensselaer II

Born at Rensselaerswyck, Stephen Van Rensselaer II (1742–1769) was a son of Elizabeth Groesbeck and Stephen Van Rensselaer I. The patroonship passed to him after the death of his father in 1747. Because Stephen was only five years old at the time of his inheritance, he did not take over the directorship of the manor until 1764, the year he married Catharine Livingston.

Very little is known of Van Rensselaer's short life. He was a captain in the Albany County militia and a colonel of the Rensselaerswyck regiment, but he is best known for overseeing the creation of the grand manor house built between 1765 and 1768. The house was scarcely completed when he died on October 19, 1769, at the age of twenty-seven. His wife and their three children, Stephen III (b. 1764), Philip Schuyler (b. 1767), and Elizabeth (b. 1768), continued to live in the house until Stephen III came of age in 1785.

Image: Portrait of Stephen Van Rensselaer II. New York Public Library

Catharine Livingston Van Rensselaer

Catharine Livingston (1745–1810) was born in Albany, a daughter of Chrystiana Ten Broeck and Philip Livingston, a powerful New York merchant and statesman who would eventually sign the Declaration of Independence. Catharine grew up between New York City and her parents' country home on Brooklyn Heights. She married Stephen Van Rensselaer II in New York City in January 1764. They had three children.

After Stephen’s death in 1769, Catharine oversaw the management of the estate. In 1775, she married Dominee Eilardus Westerlo, a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church, and had three more children. The extended family lived in the manor house until 1785, when Stephen Van Rensselaer III came of age and assumed the directorship. When Catharine died in 1810, she was living on Pearl Street in Albany.

Image: Portrait of Catharine Livingston. New York Public Library

Stephen Van Rensselaer III

Stephen Van Rensselaer III (1764–1839) was born the year work commenced on the manor house and became its most distinguished inhabitant. Educated at Princeton and Harvard, he was elected to the New York State Assembly in 1789 and to the lieutenant governorship of New York in 1795. He served as commander in chief of the New York State militia during the War of 1812 and represented New York in Congress from 1833 to 1839. As board president of the Erie Canal project, Van Rensselaer decided that the canal should run right through the manor’s east gardens, spoiling forever its tranquil setting.

He was married twice, first to Margarita Schuyler, who died in 1801, and then to Cornelia Paterson (1780–1844), the mother of nine of his eleven surviving children. Van Rensselaer died at the manor house on January 26, 1839. In his will, he divided the manor and his vast wealth between his sons Stephen and William.

Image: Chester Harding (1792–1866). Portrait of Stephen Van Rensselaer III, ca. 1828. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Mrs. J. Insley Blair, 1951 (54.51)

Cornelia Paterson Van Rensselaer

Cornelia Paterson Van Rensselaer (1780–1844) was Stephen Van Rensselaer III's second wife. She was named after her mother, Cornelia Bell Paterson. Her father, William Paterson, was a governor and chancellor of New Jersey and an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court. Cornelia and Stephen were married on May 17, 1802. She was the mother of nine of his eleven surviving children.

During Cornelia's marriage to Van Rensselaer, the manor house was a hive of political activity and lavish entertainment, attracting both foreign dignitaries and distinguished American statesmen. A noted Englishman who visited their home recalled that he "was overwhelmed by the sumptuousness of the banquet, the magnificence of the family plate and the delicacy of the wines."

Image: Nathaniel Rogers (1787–1844). Miniature Portrait of Mrs. Stephen Van Rensselaer III (Cornelia Paterson), ca. 1825. Watercolor on ivory in ormolu mat and replacement frame. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Morris K. Jesup Fund, 1932 (32.68)

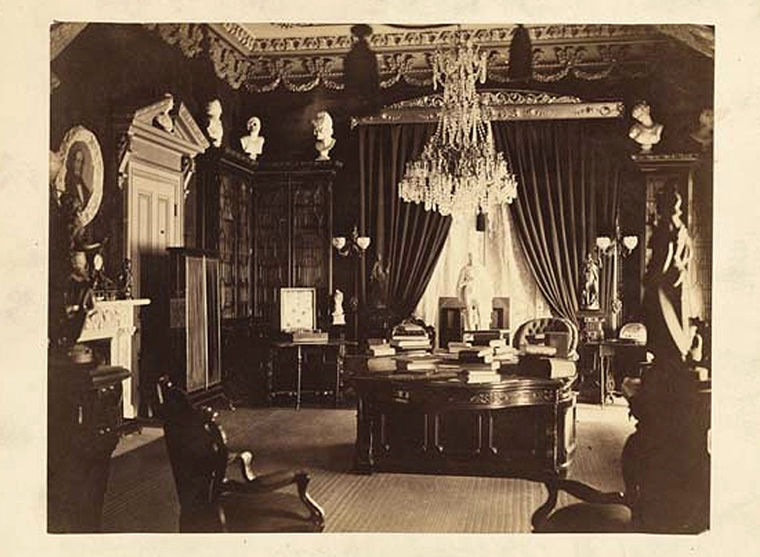

Stephen Van Rensselaer IV

Library of the manor house during the time Harriet and Stephen Van Rensselaer IV lived there. Albany Institute of History and Art

Stephen Van Rensselaer IV (1789–1868) was the eldest surviving son of Stephen Van Rensselaer III and his first wife, Margarita Schuyler. He graduated from Princeton in 1808 and later spent a year touring Europe. After he married Harriet Bayard (1799–1875) on January 2, 1817, the young couple moved into a newly built town house on North Market Street in Albany.

When Van Rensselaer was fifty years old, he inherited the manor house. He enlisted the help of the New York architect Richard Upjohn to make extensive improvements and updates. Photographs demonstrate that Harriet and Stephen filled their home with imported French furniture, paintings, sculpture, rugs, and elegant New York-made furniture from the workshops of Charles-Honoré Lannuier and Duncan Phyfe.

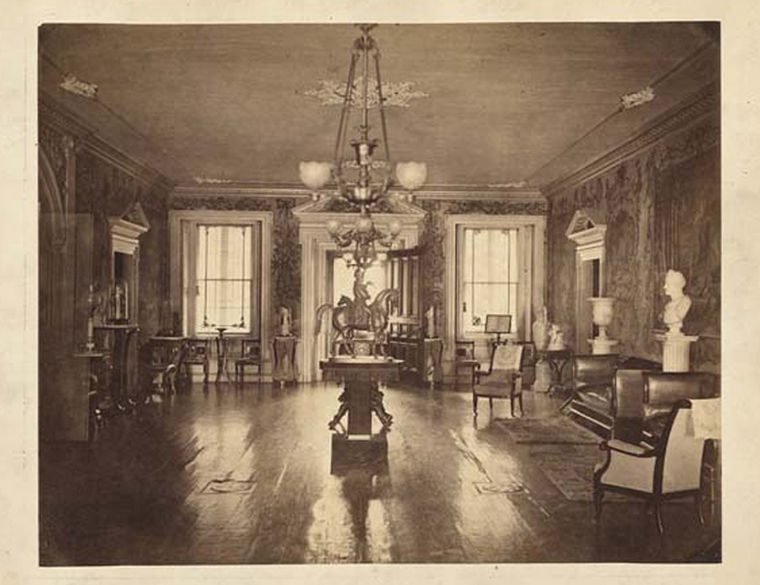

Harriet Bayard Van Rensselaer

As seen in this photograph, Harriet and Stephen Van Rensselaer IV displayed artworks and curios in the hall of the manor house. Albany Institute of History and Art

A daughter of Elizabeth and William Bayard of New York City, Harriet Elizabeth Bayard (1799–1875) was the youngest of five children. Her father was a principal in the trading firm of LeRoy, Bayard & McEvers and was one of New York's most successful entrepreneurs, acquiring great wealth in the decades following the Revolutionary War (1775–83). Described by her brother as "the greatest belle in New York," Harriet married Stephen Van Rensselaer IV at the age of eighteen in January 1817.

On the occasion of their marriage, Harriet's parents presented the young couple with furniture imported from France and commissioned from the fashionable New York cabinetmaker Charles-Honoré Lannuier. Stephen's father built them a stylish Albany town house. When the couple moved into the manor house in 1839, they brought their furniture with them.

Image: Charles-Honoré Lannuier. Card table. New York City, 1817. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Justine VR Milliken, 1995 (1995.377.1)

Dismantling the house

Sigma Phi House at Williams College, in Williamstown, Massachusetts, is a recreation of the Van Rensselaer manor house. Williams College Archives and Special Collections, Williamstown, MA

The city decided to dismantle the manor house in 1893 to gain space for development. William Bayard Van Rensselaer (1856–1909) saved the architectural woodwork and installed it in the dining room of his Albany town house. Other family members salvaged the wallpaper panels and put them in storage. Paneled doors, beams, and stone were incorporated into Sigma Phi House at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, which was designed as a replica of the manor house.

Original installation

In 1928 a group of Van Rensselaer descendants gave The Met the original woodwork and hand-painted wallpaper from their ancestral home. This gift prompted a one-story addition to the American Wing to house the reassembled Van Rensselaer Hall.

When the American Wing inaugurated a new building project in the 1970s to accommodate additional period rooms and galleries for American paintings and sculpture, Van Rensselaer Hall was relocated to the area on the second floor where it remains today.

Image: Van Rensselaer Hall made its debut at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in this 1931 addition to the American Wing. American Wing Files, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Conservation of the wallpaper

The conservation treatment of the Van Rensselaer Hall wallpaper in the 1970s entailed transferring the wallpaper from the walls onto frames for support. Then, the flaking paint was stabilized and the surface faced with tissue paper for protection during subsequent treatment. The deteriorated layers of backing papers were painstakingly removed. Finally, the wallpaper was attached to linen and secured to panels for reinstallation.

The conservation treatment of the Van Rensselaer Hall wallpaper in the 1970s entailed transferring the wallpaper from the walls onto frames for support. Then, the flaking paint was stabilized and the surface faced with tissue paper for protection during subsequent treatment. The deteriorated layers of backing papers were painstakingly removed. Finally, the wallpaper was attached to linen and secured to panels for reinstallation.

To ensure the wallpaper's continued survival, temperature controls in Van Rensselaer Hall keep the environment stable, and the wallpaper is never exposed to natural light.

Top: A conservator prepares the wallpaper to be attached to wood strips before removing it for transfer to the conservation lab

Paint analysis

The 2006 renovation of the American Wing provided an opportunity to learn more about the Van Rensselaer Hall's past. Conservators gathered tiny paint samples near the cornice and spandrel of the archway. Looking at the samples under magnification revealed eight generations, or layers, of paint.

The first generation was a gold color, applied over a primer made of coarsely ground brownish paint. To reproduce the color, viscosity, and gloss of this original layer, conservators ground and mixed the paints by hand, then applied them with special brushes. Van Rensselaer Hall now comes as close as possible to its original appearance.

Image: Dark brown primer contrasts with the cream-colored finish in this magnified cross section of the paint layers from the Van Rensselaer Hall. Courtesy Susan L. Buck

Wallpaper designs

An alternate view of Van Rensselaer Hall featuring its impressive wallpaper designs.

The wallpaper in this room covers an area of more than six hundred square feet and it comprises twenty-seven scenic and decorative panels. Large trompe-l'oeil frames contain images of classical ruins. Smaller cartouches represent the four seasons, while trophy panels flanking the east and west doorways depict earth, air, fire, and water. Masks bracketed by cornucopias and floral swags top the windows, and acanthus motifs crown the side doorways.

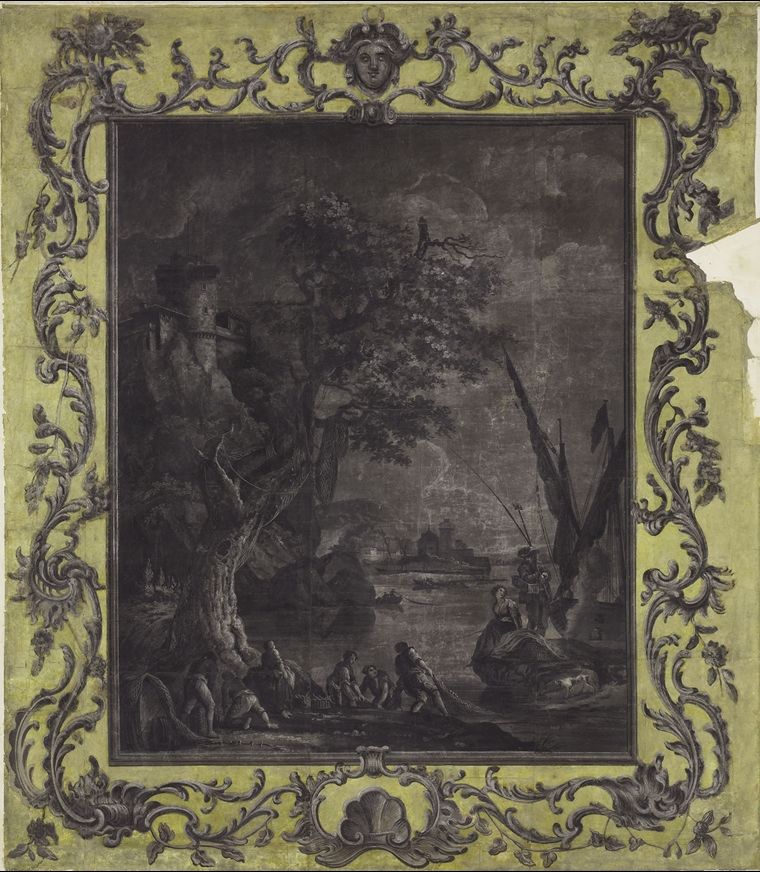

Scenic panel, View of Pozzouli

View of Pozzouli, England, ca. 1768. Tempera on watercolor paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Dr. Howard Van Rensselaer, 1928 (28.224i)

View of Pozzouli is based on an engraving by Jean Jacques Le Veau (1729–1786), Vue pres Pouzzol au Golfe de Naples, that was adapted from a painting by Charles Francois Lacroix (d. 1782).

Scenic panel, Roman Ruins

Roman Ruins England, ca. 1768 Tempera on watercolor paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Dr. Howard Van Rensselaer, 1928 (28.224l)

Roman Ruins England, ca. 1768 Tempera on watercolor paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Dr. Howard Van Rensselaer, 1928 (28.224l)

Roman Ruins was based on an unidentified print after a painting by Giovanni Paolo Panini (1691–1765).

Scenic panel, Naples and Mount Vesuvius

Naples and Mount Vesuvius England, ca. 1768. Tempera on watercolor paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Dr. Howard Van Rensselaer, 1928 (28.224o)

Naples and Mount Vesuvius was based on an engraving by Nicolas Larmessin IV (1684–1755) that was adapted from a painting by Nicolas Lancret (1690–1743).

Scenic panel, Cascade of Tivoli

Cascade of Tivoli, England, ca. 1768. Tempera on watercolor paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Dr. Howard Van Rensselaer, 1928 (28.224u)

Cascade of Tivoli is based on an engraving by Jean Jacques Le Veau (1729–1786), La Cascade de Tivoli, which was adapted from a painting by Charles Francois Lacroix (d. 1782)

Scenic panel, View near Mont Ferrat

Jean Jacques Le Veau. Vue proche du Mont-Ferrat. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1953 (53.600.1633)

View near Mont Ferrat is based on an engraving by Jean Jacques Le Veau (1729–1786), Vue proche du Mont-Ferrat, which is after a painting by Joseph Vernet (1714–1789).

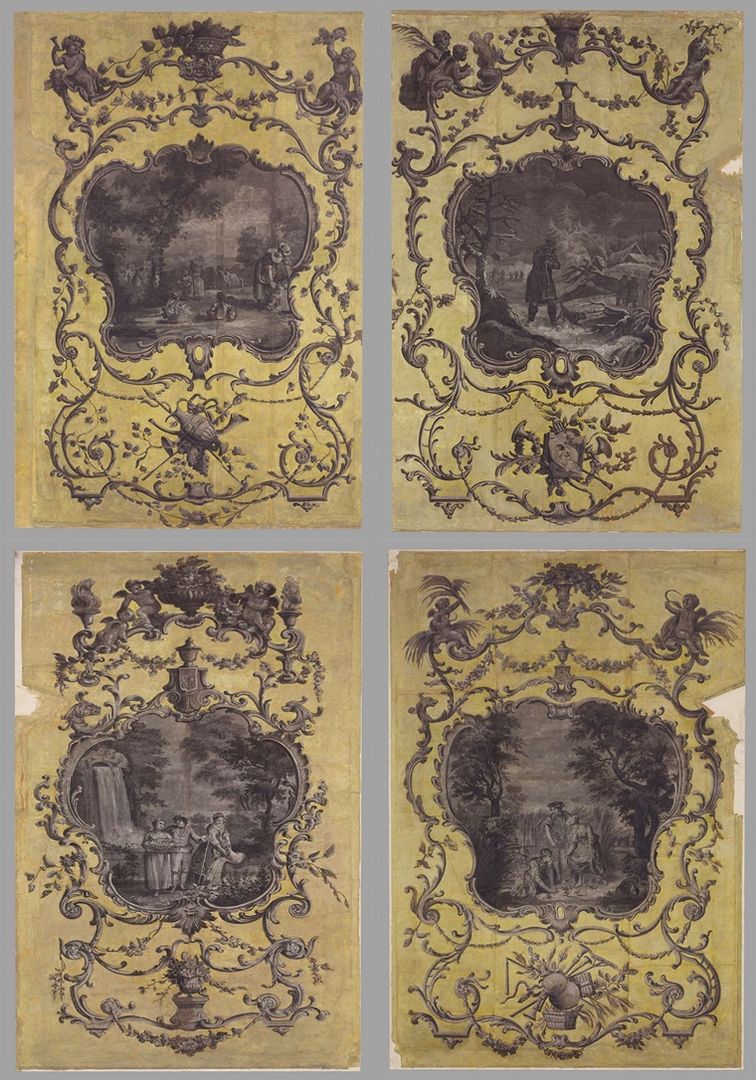

Seasons: Autumn, Winter, Spring, and Summer

Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter, Wallpaper, England ca. 1768. Tempera on watercolor paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Dr. Howard Van Rensselaer, 1928 (28.224w,a,k,m)

This series of panels depicts the four seasons. All four were modeled on engravings by Nicolas Larmessin IV (1684–1755) that were adapted from paintings by Nicolas Lancret (1690–1743).

Trophies: Water, Air, Earth, and Fire

Trophies: Earth, Fire, Air, and Water Wallpaper, England, ca. 1768. Tempera on watercolor paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Dr. Howard Van Rensselaer, 1928 (28.224q,e,s,g)

This series of trophies was based on engravings by Gabriel Huquier (1695–1772) after designs by Maurice Jacques (1712–1784), an artist at the Gobelin tapestry manufactory in Paris.

Step inside Van Rensselaer Hall

Click and drag this Google Arts and Culture museum view to step inside Van Rensselaer Hall and surround yourself with its ornate Rococo wallpaper.

Keep Learning

American Georgian Interiors (Mid-Eighteenth-Century Period Rooms)

Read more about American Georgian Interiors in this Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History essay.

Paris – New York

Learn more about the card table featured in the Van Rensselaer Hall, designed by Charles-Honoré Lannuier in 1817, in this 82nd & Fifth video narrated by curator Peter Kenny.