Some of the most dramatic stone architectural monuments in eastern and southern Africa were produced during the first half of the second millennium A.D. Two of these, Lalibela in present-day Ethiopia and Great Zimbabwe, have been marked for preservation and included on UNESCO’s World Heritage List. The stone-cut churches of Lalibela may be the oldest preserved architectural structures on the continent and remain a site of work, study, and worship for an active religious community who believe Lalibela to be the new Jerusalem. The churches are also popular pilgrimage sites for Coptic priests and lay worshippers. Stone ruins today mark the location of several capital cities in medieval southern Africa. Best known among these is Great Zimbabwe, whose Great Enclosure is the largest ancient structure in sub-Saharan Africa. Known especially for their massive stone structures, these cities also produced distinctive pottery, soapstone carving, and ivory work and developed extensive gold and copper mining industries.

Eastern and Southern Africa, 1000–1400 A.D.

Timeline

1000 A.D.

1100 A.D.

1100 A.D.

1200 A.D.

1200 A.D.

1300 A.D.

1300 A.D.

1400 A.D.

Overview

Key Events

-

ca. 1050–1270

The settlement of Mapungubwe, located in the Limpopo River valley of present-day Zimbabwe, is supported by an economy based on livestock and trade. By controlling the flow of cattle and goods such as ivory, rhinoceros horn, and gold, the elite of Mapungubwe create status divisions that are reinforced with visual metaphors. Living atop the hill on which the site was founded, they remove themselves from the rest of the community behind monumental walls. Ivory hunting, copper mining, and trade in gold are important activities of the Mapungubwe rulers. Craftsmen develop the art of metalwork, particularly gold, creating gold bangles, beads, and, most notably, gold-plated rhinoceros sculptures. Engaged in commerce with the Swahili coast, traders from Mapungubwe exchange their goods for glass beads, cloth, and Chinese celadon. The city is abandoned shortly after Great Zimbabwe’s rise to prominence in the thirteenth century.

-

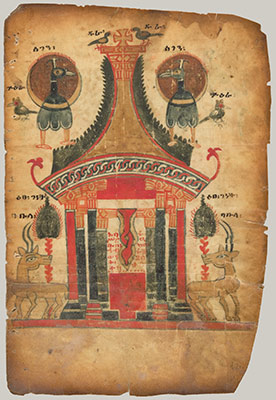

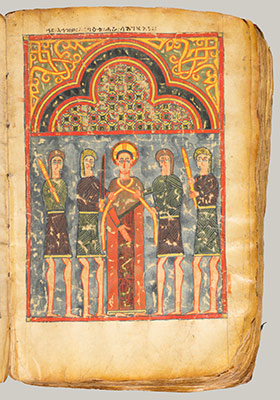

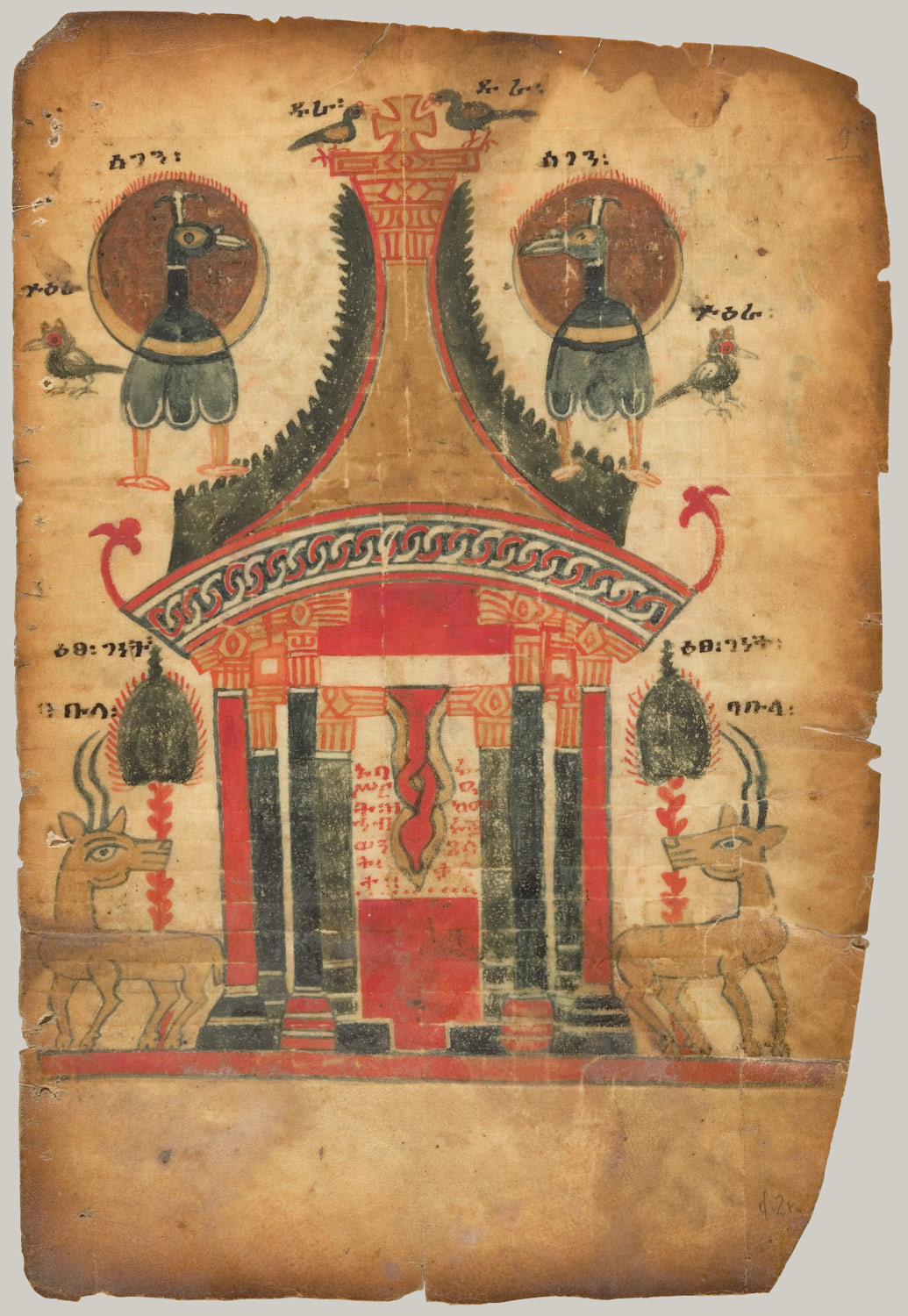

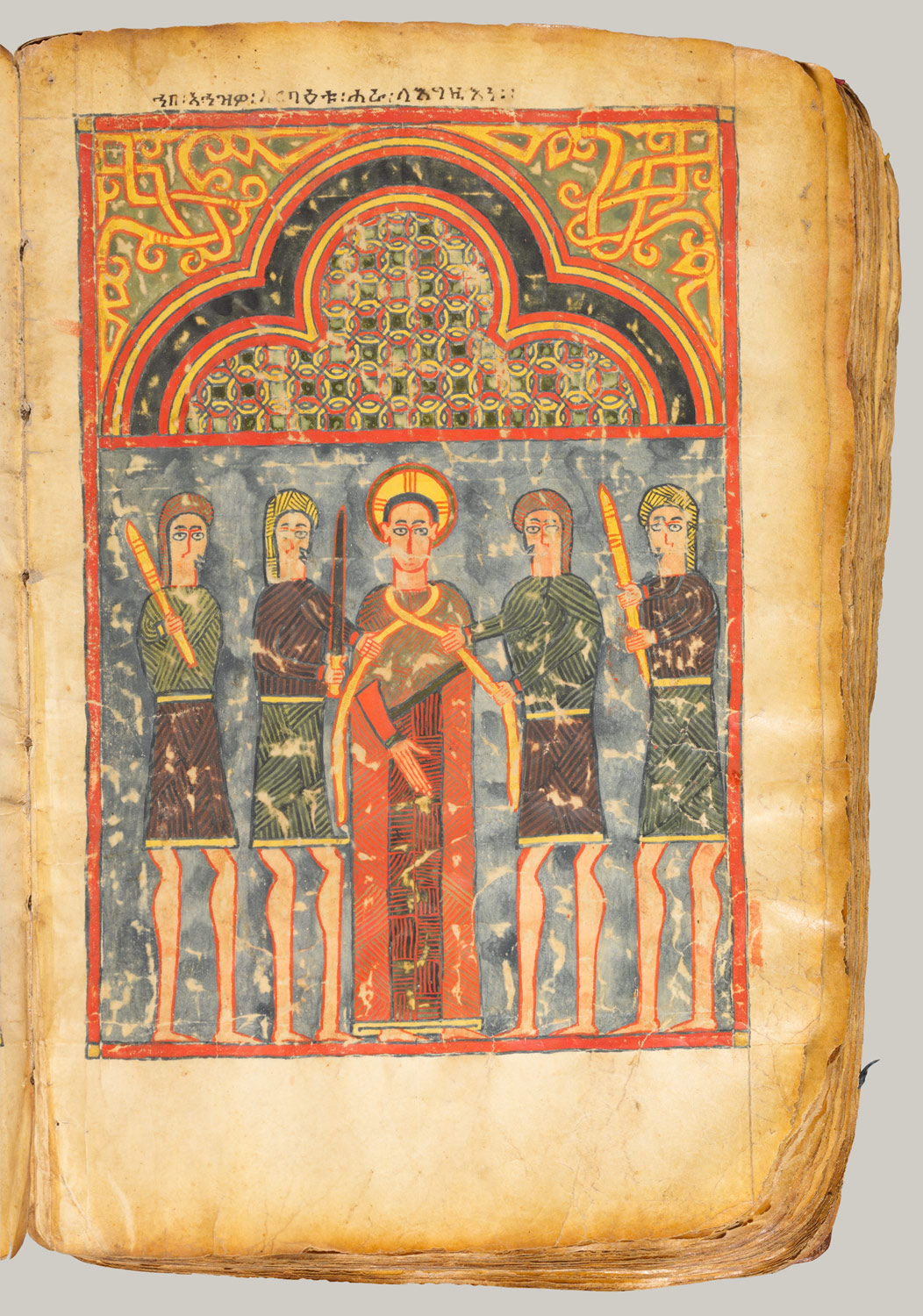

ca. 12th–13th century

At the site in Ethiopia now called Lalibela (after the ruler Lalibela, r. late 12th–early 13th century), a group of churches are carved directly from the rock of the Lasta Mountains under the auspices of the Zagwe dynasty. Like the monuments and tombs of Aksum, these buildings are carved to look as though they were conventionally built from assembled materials but in fact are hewn from unified masses of stone. This complex of eleven churches, originally called Roha (Arabic for Edessa, a reference to the city blessed by Christ), evokes multiple sites intended to associate the Zagwes with strong religious and political predecessors. In addition to being a new incarnation of Edessa, with all the divine favor implied by that status, Lalibela is intended to represent a new Jerusalem. Areas within the Lalibela complex replicate the names of holy sites such as the church of Golgotha, strengthening these associations with visual cues. The Church of the Redeemer, for example, makes explicit political reference to Aksum, quoting the architectural structure of Aksum’s famous cathedral, Our Lady Mary of Zion. After becoming associated with the Ethiopian saint Lalibela in the early fifteenth century, Lalibela’s meaning shifts and the complex develops into a thriving pilgrimage center.

-

ca. 13th century

The Swahili culture, reflecting the settlement of Muslim Arab merchants along the eastern coast and their intermixture with local East African peoples, becomes well established in powerful trading centers. The rise of the Swahili town of Kilwa coincides with the ascendance of Great Zimbabwe, which supplies Kilwa with ivory, gold, and food.

-

ca. 13th century

The first stages of the Great Mosque of Kilwa and the secular palace complex of Husuni Kubwa are erected in what is now Tanzania. These buildings, constructed of local coral blocks, represent the first and finest flowering of Swahili architecture. Although stylistic influences can be traced to sources as disparate as Arabia and India, the synthesis achieved here is distinct to the Swahili coast.

-

ca. 1250–1450

Great Zimbabwe is founded by Bantu-speaking ancestors of the Shona people. Like its predecessor Mapungubwe, Great Zimbabwe’s economy is based on cattle and supplemented by trade. The city utilizes the stone wall of the plateau region on a scale never equalled thereafter. The sinuous, massive walls of its complexes reach a height of 36 feet in some areas, constructed entirely without mortar from slabs of stone. These walls adjoin clay and wattle huts to form elaborate courtyards intended to house the ruling elite. Beyond architecture, Great Zimbabwe produces little in the way of visual art, with one significant exception: the soapstone birds combining human and animal features, which are later adopted as national symbols (one currently adorns the flag of Zimbabwe).

Citation

“Eastern and Southern Africa, 1000–1400 A.D.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/?period=07®ion=afa (October 2001)