With the rise of powerful dynasties and continuing trade between the Mediterranean and India, Egypt becomes pivotal in the late medieval era as one of the most important commercial centers of the medieval world. Along with this power and prosperity, Cairo’s role as cultural capital of the Islamic world is reflected in the arts and architecture of the period.

Egypt, 1000–1400 A.D.

Timeline

1000 A.D.

1100 A.D.

1100 A.D.

1200 A.D.

1200 A.D.

1300 A.D.

1300 A.D.

1400 A.D.

Overview

Key Events

-

996–1021

The reign of Fatimid caliph al-Hakim, who rededicates the mosque begun by his father, al-‘Aziz (r. 975–96). The Mosque of al-Hakim, an important example of Fatimid architecture and architectural decoration, plays a critical role in Fatimid ceremonies and processions, which emphasize the religious and political role of the Isma‘ili Shi‘a caliph.

-

ca. 1000

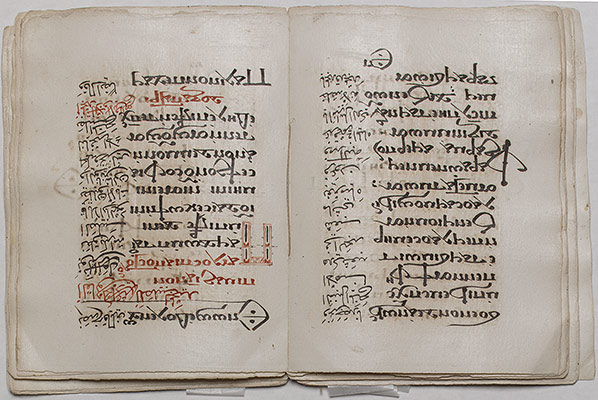

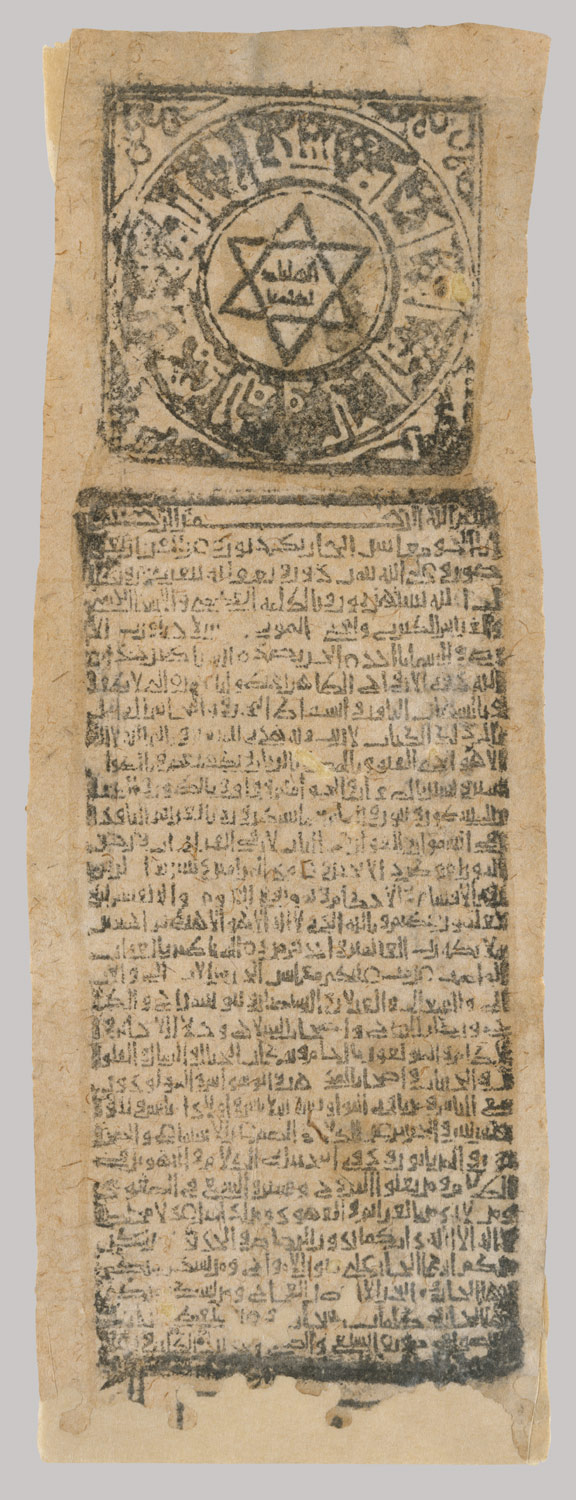

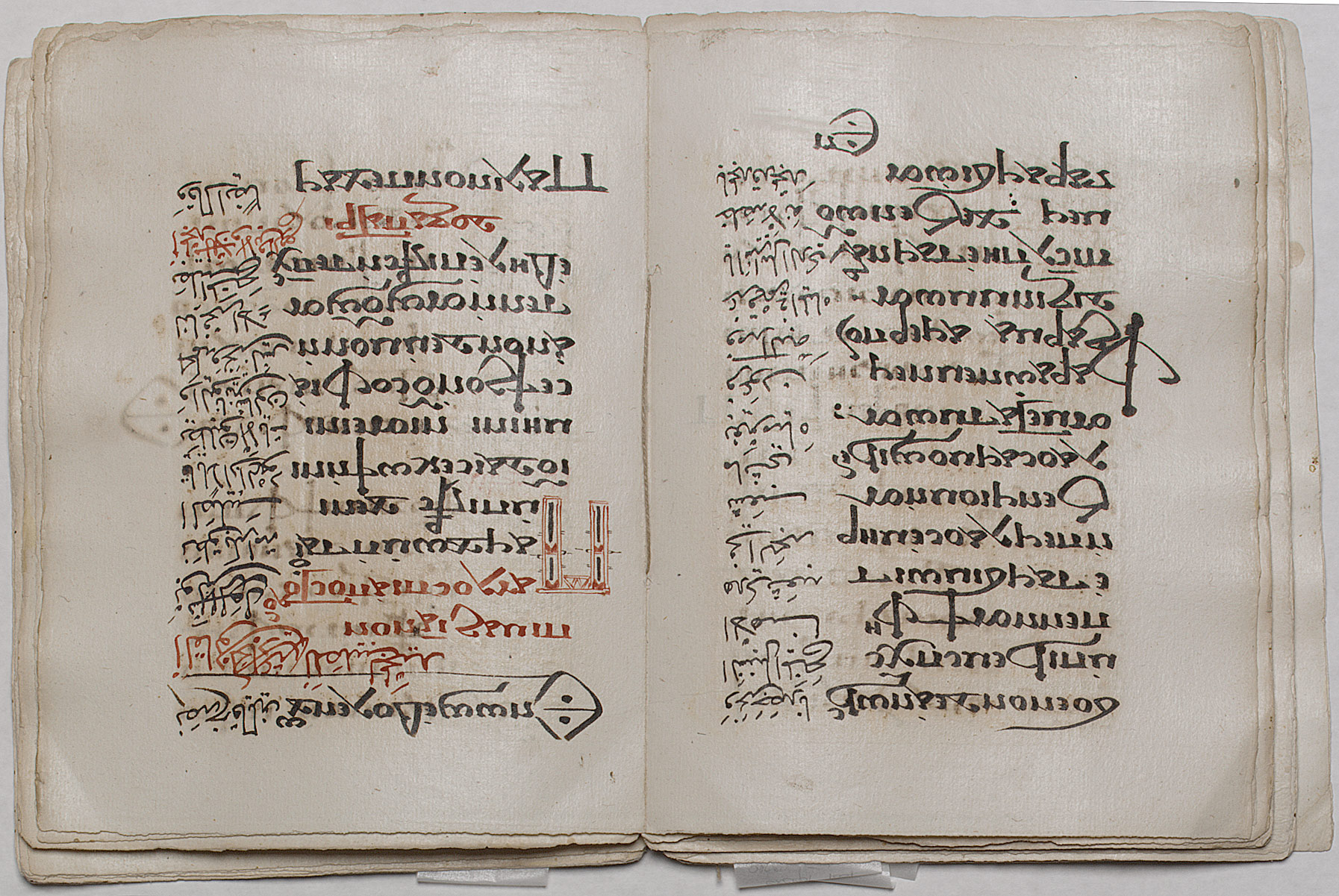

Arabic, used by the Muslim rulers of Egypt, is introduced as a language for the public performance of church ceremony in the Coptic Church. Ecclesiastical manuscripts are increasingly bilingual, with juxtaposed columns of Coptic and Arabic.

-

1047–1077

Christodoulos transfers the patriarchate from Alexandria to the administrative capital in Cairo, establishing it as the new, permanent seat of the Coptic Church.

-

1087 and 1092

The powerful Fatimid amir and vizier Badr al-Jamali (r. 1073–94) commissions monumental gates for Cairo’s city walls (Bab al-Futuh and Bab al-Nasr, 1087, Bab al-Zuwayla, 1092). The stonework of the gates, built by Armenian architects from Edessa (modern Urfa in southeastern Turkey), incorporates the latest defense devices developed in northern Mesopotamia.

-

ca. 11th century

Along with Cairo, elaborate Fatimid funerary structures are built at Aswan in Upper Egypt.

-

1125

The vitality of Fatimid architecture continues, as exemplified by the construction of the Mosque of al-Aqmar.

-

1160–1171

Zangid general Salah al-Din (Saladin) repulses a Crusader army that reaches the gates of Cairo (1160s). In 1171, he declares the Fatimid caliphate to be at its end and establishes the Ayyubid dynasty in Syria and Egypt.

-

1171–1252

Along with their renown in the arts of inlaid metalwork and pottery (luster- and underglaze-painted wares), the Ayyubids are also great builders. The Coptic architects Abu Mansur and Abu Mashkur are commissioned by Saladin to design the citadel and circuit walls of Cairo (1187). Other important monuments in Cairo include the Mausoleum of Imam al-Shafi‘i (1211), the Tomb of the Abbasid Caliphs (1242–43), and the Madrasa and Mausoleum of Salih Najm al-Din Ayyub (1243–50).

-

1218–1221

During the Fifth Crusade, Coptic Christians defend the city of Damietta, controlled by the Muslim Ayyubids, against Western Christian armies.

-

1218–1238

The reign of Ayyubid caliph al-Kamil marks a high point in tolerance of the Coptic Church in Muslim Egypt during the later Middle Ages.

-

1250–1517

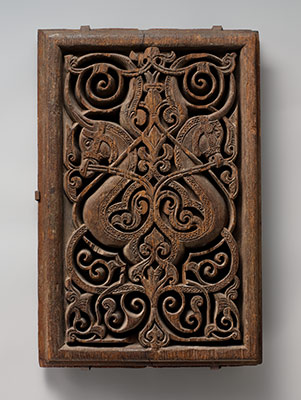

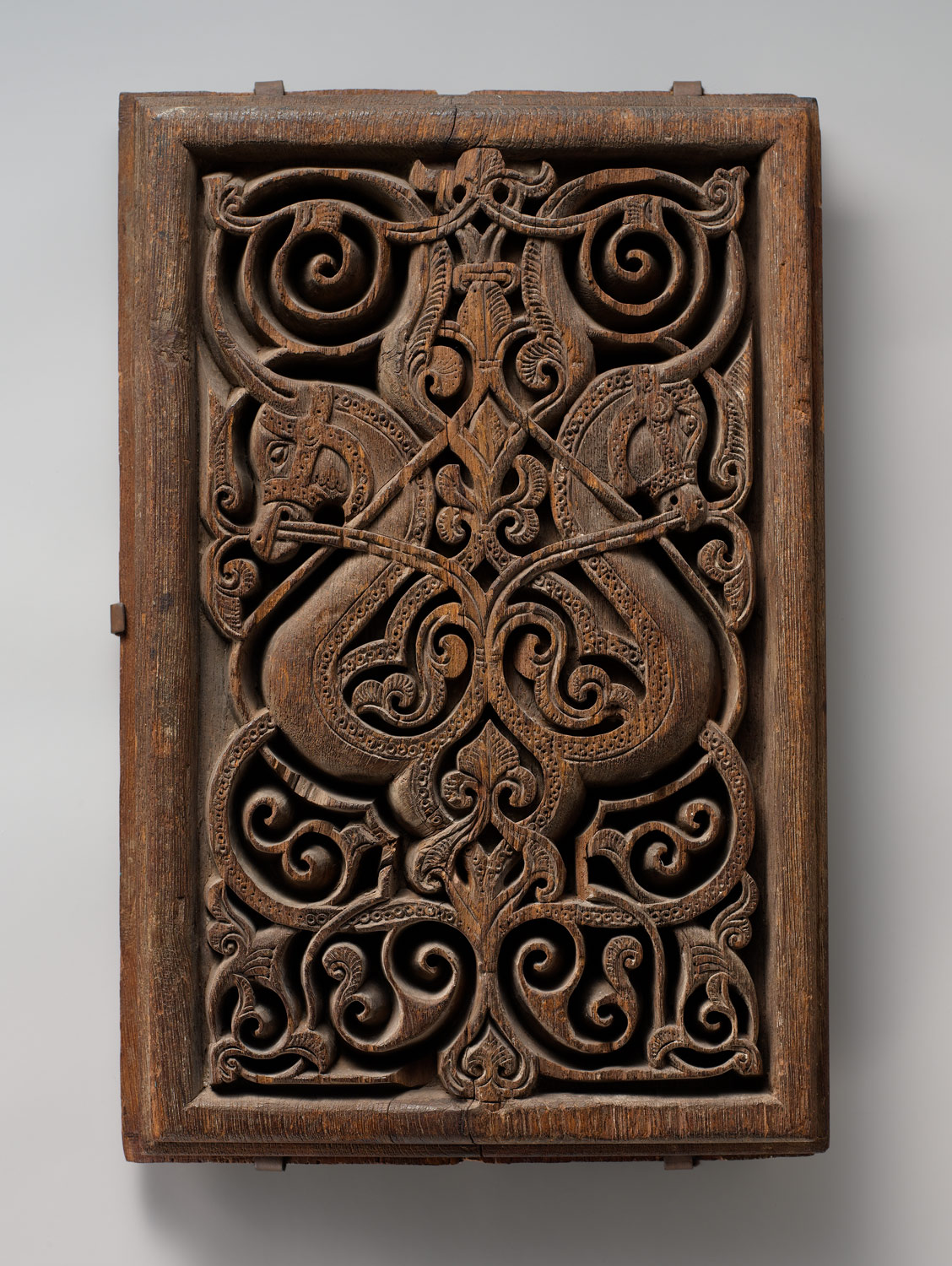

The Mamluk sultanate emerges from the weakening of the Ayyubid kingdoms in Egypt and Syria (1250–60). Although former military slaves, the Mamluks create the greatest Islamic empire of the later Middle Ages and overcome the threats presented by the Crusaders and Mongols. The Mamluk realm benefits from the east-west trade of silks and spices. The arts flourish, especially enameled glass, inlaid metalwork, woodwork, and textiles, and a great many religious and public monuments are built, which today still form the core of medieval Cairo.

-

1260–1277

Besides military successes, the reign of the first Mamluk sultan Baibars al-Bunduqdari, a Qipchaq Turk, is defined by important building activity for public and pious foundations. In Cairo, Baibars commissions the Madrasa Zahiriya (1262–63; destroyed nineteenth century) and a congregational mosque (1266–69).

-

ca. 1280–1400

Mamluk architectural patronage focuses on public and pious foundations, including madrasas, mausolea, minarets, and, in some cases, hospitals. Such foundations ensure the survival of the patron’s wealth and perpetuate his name, both of which are threatened by problems relating to inheritance and confiscation of family fortunes. Important commissions by Mamluk sultans include the complexes of Qalawun (1283–85), al-Nasir Muhammad (1295–1304), Hasan (begun 1356), and Barquq (1384–86).

-

1382

The source of Turkic slaves who made up the Bahri line of Mamluk sultans dries up. This, along with intense strife in the Mamluk corps, brings a new elite of Mamluks to power, recruited from Circassian slaves and known as the Burji. Sultan Barquq (r. 1382–99) is the first ruler of this line.

Citation

“Egypt, 1000–1400 A.D.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/?period=07®ion=afe (October 2001)