Surrealism Beyond Borders

Introduction

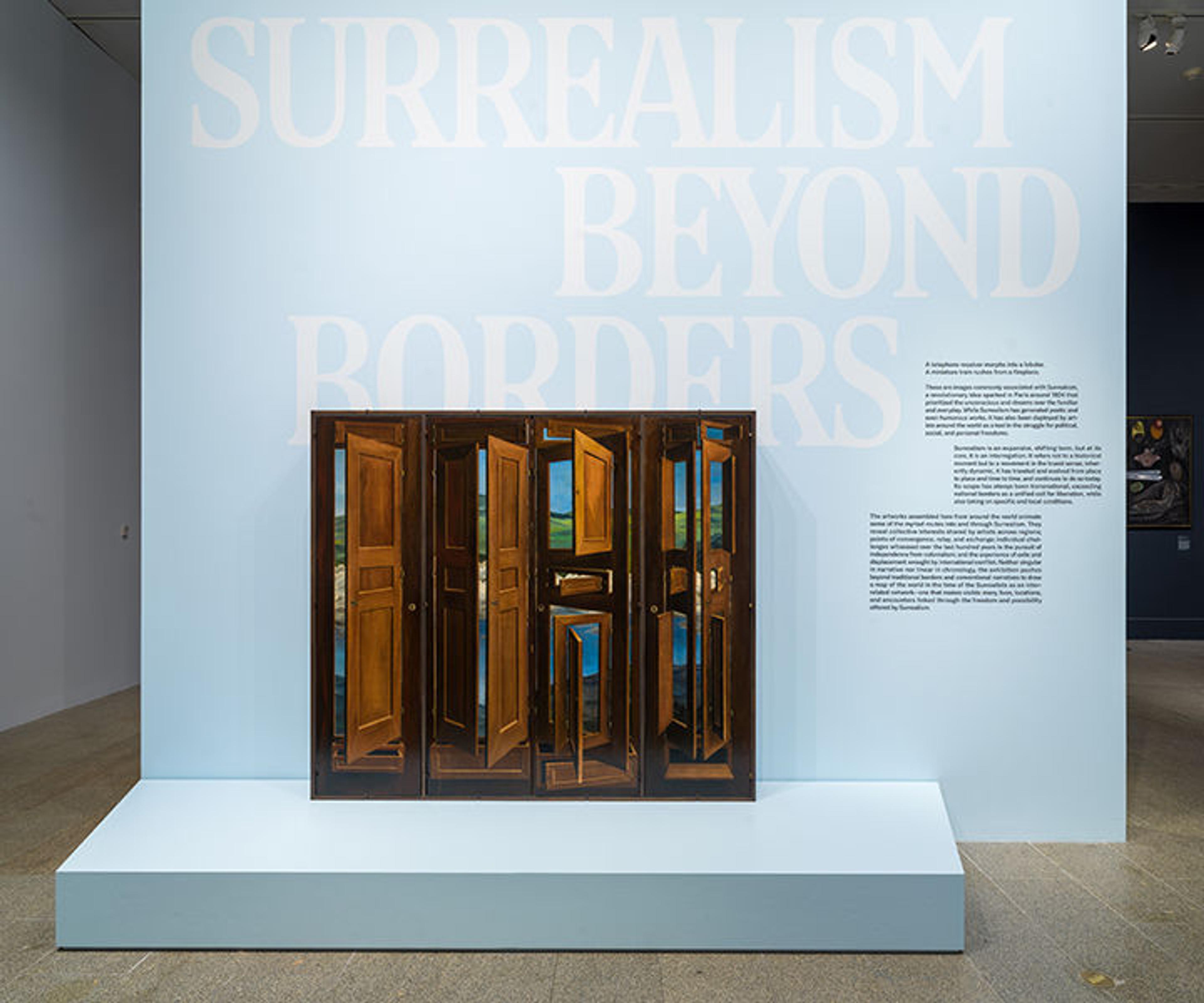

A telephone receiver morphs into a lobster. A miniature train rushes from a fireplace. These are images commonly associated with Surrealism, a revolutionary idea sparked in Paris around 1924 that prioritized the unconscious and dreams over the familiar and everyday. While Surrealism has generated poetic and even humorous works, it has also been deployed by artists around the world as a tool in the struggle for political, social, and personal freedoms.

Surrealism is an expansive, shifting term, but at its core, it is an interrogation. It refers not to a historical moment but to a movement in the truest sense; inherently dynamic, it has traveled and evolved from place to place and time to time, and continues to do so today. Its scope has always been transnational, exceeding national borders as a unified call for liberation, while also taking on specific and local conditions.

The artworks assembled here from around the world animate some of the myriad routes into and through Surrealism. They reveal collective interests shared by artists across regions; points of convergence, relay, and exchange; individual challenges witnessed over the last hundred years in the pursuit of independence from colonialism; and the experience of exile and displacement wrought by international conflict. Neither singular in narrative nor linear in chronology, the exhibition pushes beyond traditional borders and conventional narratives to draw a map of the world in the time of the Surrealists as an interrelated network—one that makes visible many lives, locations, and encounters linked through the freedom and possibility offered by Surrealism.

Collective Identities

Surrealism depends upon a collective body committed to going beyond what can be done by the individual in isolation, often in response to political or social concerns. Viewed across time and place, this quality has manifested in group exhibitions and demonstrations, cowritten manifestos and declarations, and broadly shared and circulated values.

Collaborative pursuits could release what Simone Breton, an early participant in Surrealism in Paris, called “images unimaginable by one mind alone.” Examples of such generative activities include seánce-like explorations of trances by Breton and her colleagues, questionnaires published in the Belgrade Surrealist Circle’s journal, and the Chicago Surrealists’ spoken-word poetry performed with musicians. This collectivity has been expressed through art making, especially in cadavre exquis (exquisite corpse) drawings and assembled works. Group production underscores proximity and intimacy, as with Frida Kahlo and Lucienne Bloch’s examples here, but it also makes visible diasporic communities—such as the one formed in 1970s Paris by artists from Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Haiti, and the United States, alongside poet Joyce Mansour.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

De Schone Zakdoek

Between April 1941 and February 1944, Gertrude Pape and Theo van Baaren produced the journal De Schone Zakdoek (The Clean Kerchief) in Utrecht (the motto above appeared in its pages). While not specifically associated with Surrealism, it was made in close alignment with the movement’s tenets and practices. Collectivity was key: the publication emerged from Monday-night gatherings in Pape’s apartment with friends, many of whom were poets, authors, and artists. Together they engaged in discussions, wrote poetry, made cadavre exquis (exquisite corpse) drawings and objects, played games, and held occasional séances.

They created the journal in secret during Utrecht’s Nazi occupation, with precious and rationed materials. Each issue was made by hand in a single copy, reducing the possibility of wartime censorship and ensuring the inclusion of original artwork. By March 1944 enforced curfews had made the Monday-night events impossible; the gatherings had already become monthly due to heightened travel restrictions. Several contributors had gone underground by then, including Van Baaren, who since 1942 had been hiding in Pape’s apartment to avoid Arbeitseinsatz (forced labor internment). With the group unable to meet, the journal ended. De Schone Zakdoek remained virtually unknown for decades, due to its lack of a print run and to the clandestine circumstances of its manufacture.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

The Work of Dreams

As a form of interrogation, Surrealism has questioned—and sometimes attempted to overthrow—the stronghold of consciousness and control. Dreams are critical in this because, like hallucinations and delusions, they can reveal the workings of the unconscious mind. Sigmund Freud’s widely translated book The Interpretation of Dreams (1900) proved an early, vital stimulus for many artists’ approaches to Surrealism. Through case studies of his patients, Freud observed that dreams exposed emotions otherwise repressed by social convention.

Max Ernst’s painting draws upon such an experience: a “fever vision” in which the artist saw forms appear in the graining of wood paneling. Fantastical juxtapositions (as in Yves Tanguy’s canvas, made after travel to North Africa, and in Dorothea Tanning’s nocturnal scene), or nightmarish subjects (such as Rita Kernn-Larssen’s recollection of a drowning) capture the sense of the ordinary made unfamiliar. Seizing upon this potential for liberation, artists associated with Surrealism in various locations have sought the inspiration of dreams to break from limitations imposed by custom or to bring the self, community, or work of art beyond the reach of waking reality.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

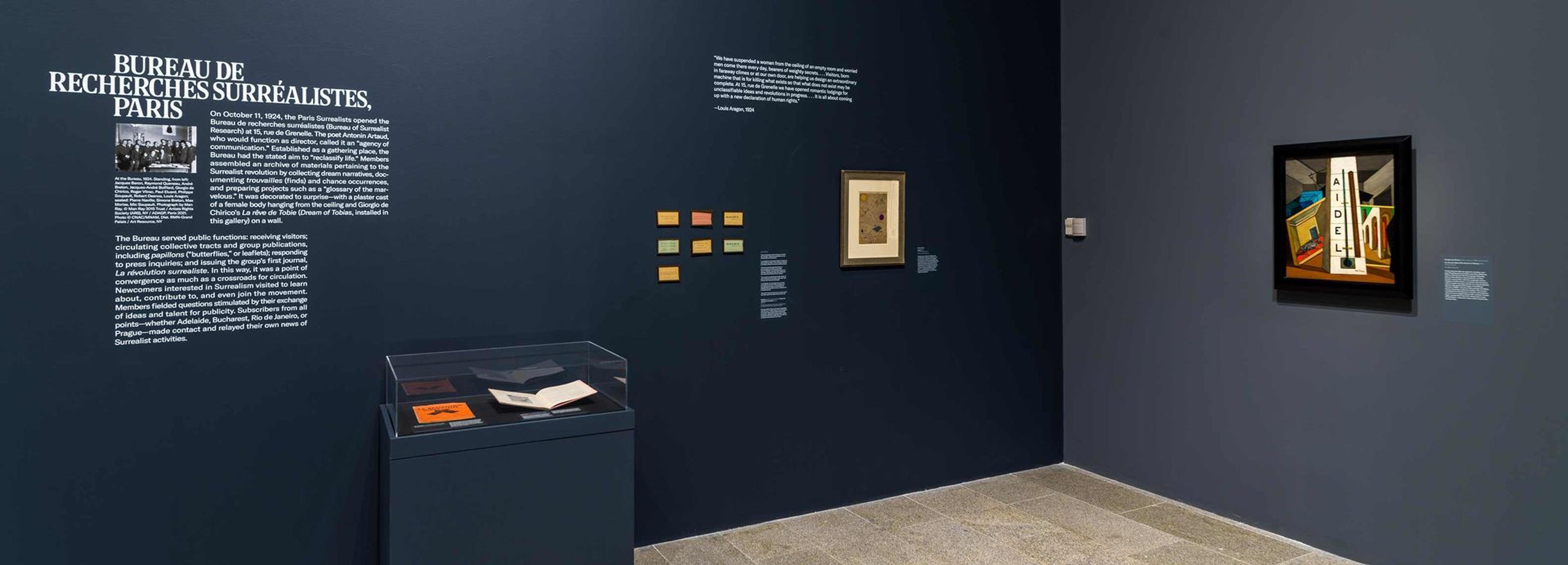

Bureau de Recherches Surréalistes, Paris

On October 11, 1924, the Paris Surrealists opened the Bureau de recherches surréalistes (Bureau of Surrealist Research) at 15, rue de Grenelle. The poet Antonin Artaud, who would function as director, called it an “agency of communication.” Established as a gathering place, the Bureau had the stated aim to “reclassify life.” Members assembled an archive of materials pertaining to the Surrealist revolution by collecting dream narratives, documenting trouvailles (finds) and chance occurrences, and preparing projects such as a “glossary of the marvelous.” It was decorated to surprise—with a plaster cast of a female body hanging from the ceiling and Giorgio de Chirico’s La rêve de Tobie (Dream of Tobias, installed in this gallery) on a wall.

The Bureau served public functions: receiving visitors; circulating collective tracts and group publications, including papillons (“butterflies,” or leaflets); responding to press inquiries; and issuing the group’s first journal, La révolution surréaliste. In this way, it was a point of convergence as much as a crossroads for circulation. Newcomers interested in Surrealism visited to learn about, contribute to, and even join the movement. Members fielded questions stimulated by their exchange of ideas and talent for publicity. Subscribers from all points—whether Adelaide, Bucharest, Rio de Janeiro, or Prague—made contact and relayed their own news of Surrealist activities.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Beyond Reason

In Western Europe, logic has been rooted in the history of the Enlightenment, the intellectual movement of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that promoted science, empirical knowledge, and reason as the hallmarks of society. For Surrealists and those sympathetic to their interests, especially in Europe and North America, rejecting this heritage of rationalism has meant liberating the mind from outdated modes of thought and behavior. Artists have sought to challenge “order” by merging disjunctive form and scale with visual precision, in the example of René Magritte, or, as with Gerome Kamrowski, including encyclopedia-like illustration in compositions that are anything but rational.

This aspect of Surrealism, however, has also been adapted to address more national concerns. In Japan, for instance, a country that absorbed Surrealist ideas and relayed them elsewhere in Asia, some artists—confronted with criticism of the movement as escapist—sought to distinguish their approach, identifying “rishi [reason] as its only weapon.” They proposed “an even higher form of Surrealism—a new Surrealism which is Scientific Surrealism.” In the late 1920s and early 1930s, various forms of Surrealism in Japan both celebrated and interrogated modern technologies, science, and reason in order to question the meaning of art, conventional ways of thinking, and cultural norms.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

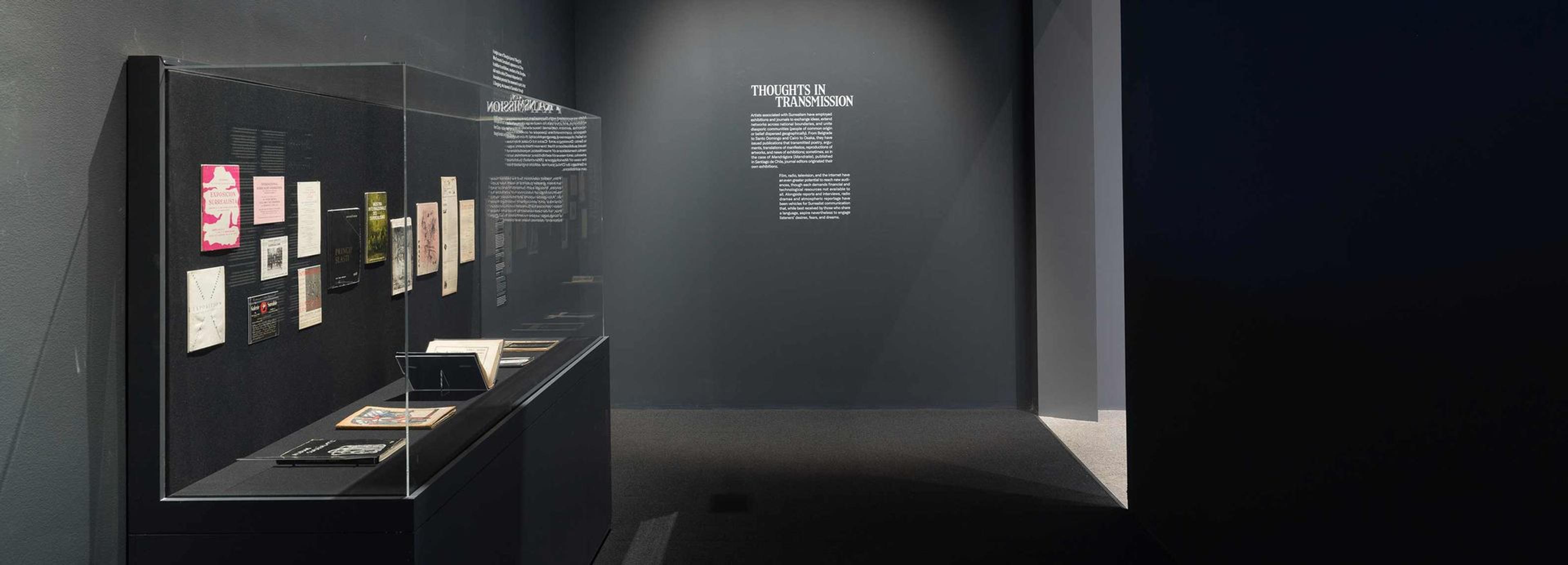

Thoughts in Transmission

Artists associated with Surrealism have employed exhibitions and journals to exchange ideas, extend networks across national boundaries, and unite diasporic communities (people of common origin or belief dispersed geographically). From Belgrade to Santo Domingo and Cairo to Osaka, they have issued publications that transmitted poetry, arguments, translations of manifestos, reproductions of artworks, and news of exhibitions; sometimes, as in the case of Mandrágora (Mandrake), published in Santiago de Chile, journal editors originated their own exhibitions.

Film, radio, television, and the internet have an even greater potential to reach new audiences, though each demands financial and technological resources not available to all. Alongside reports and interviews, radio dramas and atmospheric reportage have been vehicles for Surrealist communication that, while best received by those who share a language, aspire nevertheless to engage listeners’ desires, fears, and dreams.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Poetic Objects

Making Surrealist objects—in addition to harnessing dreams, subverting reason, or summoning the unconscious—can be a powerful way to challenge the everyday. The works are less about thwarting the tradition and conventional look of sculpture than about reinvesting reality with what poet André Breton called a “derangement of the senses.” Often made with found or discarded nontraditional art materials, these curious assemblages produced by artists connected to Surrealism draw their impact from the imaginative spark lit by the joining of otherwise unrelated elements.

Wolfgang Paalen, working in Mexico, described them as “time-bombs of the conscience,” while Salvador Dalí called them “absolutely useless from a practical and rational point of view and created wholly for the purpose of materializing in a fetishistic way, with maximum tangible reality, ideas and fantasies of a delirious character.” In their medium and manufacture, objects such as those by Joyce Mansour and Eileen Agar shown here could produce an unexpected, magnetic draw. Ladislav Zívr, who came to identify with Surrealism after attending art school in Prague, saw in his Incognito Heart an “emotional manifestation, intended to reveal the spiritual unknown inside us—to, in fact, discover us.” At their most powerful, poetic objects escape any single interpretation.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

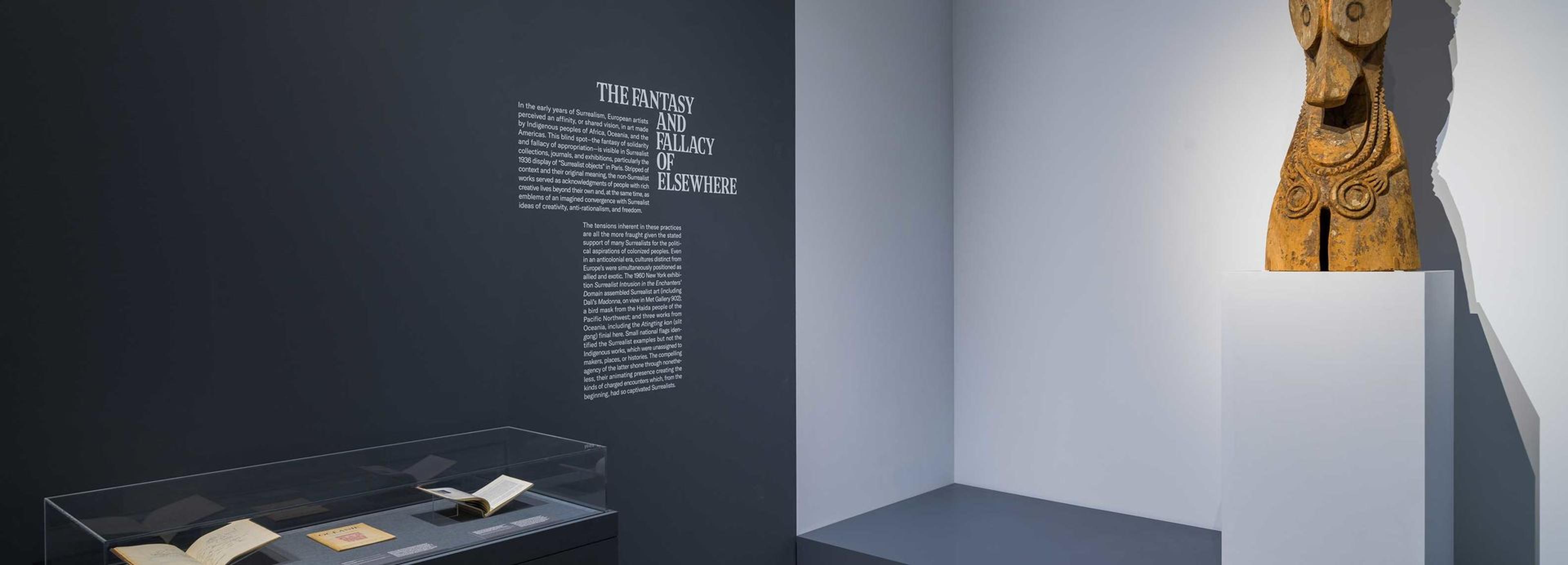

The Fantasy and Fallacy of Elsewhere

In the early years of Surrealism, European artists perceived an affinity, or shared vision, in art made by Indigenous peoples of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas. This blind spot—the fantasy of solidarity and fallacy of appropriation—is visible in Surrealist collections, journals, and exhibitions, particularly the 1936 display of “Surrealist objects” in Paris. Stripped of context and their original meaning, the non-Surrealist works served as acknowledgments of people with rich creative lives beyond their own and, at the same time, as emblems of an imagined convergence with Surrealist ideas of creativity, anti-rationalism, and freedom.

The tensions inherent in these practices are all the more fraught given the stated support of many Surrealists for the political aspirations of colonized peoples. Even in an anticolonial era, cultures distinct from Europe’s were simultaneously positioned as allied and exotic. The 1960 New York exhibition Surrealist Intrusion in the Enchanters’ Domain assembled Surrealist art (including Dalí’s Madonna, on view in Met Gallery 902); a bird mask from the Haida people of the Pacific Northwest; and three works from Oceania, including the Atingting kon (slit gong) finial here. Small national flags identified the Surrealist examples but not the Indigenous works, which were unassigned to makers, places, or histories. The compelling agency of the latter shone through nonetheless, their animating presence creating the kinds of charged encounters which, from the beginning, had so captivated Surrealists.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Cairo

In the months before the outbreak of World War II, and with European nationalism on the rise, Surrealist sympathizers in Cairo formed a critical point of convergence. The group issued a manifesto in December 1938 written by Georges Henein with thirty-seven signatories. Its title, Yahya al-fann al-munhatt/Vive l’art dégénéré (Long Live Degenerate Art), references the Nazis’ mockery of modernist art as “degenerate.”

The group of artists and writers known as al-Fann wa-l-Hurriyya/Art et Liberté (Art and Liberty), used both the Arabic and French terms for “free art” as the framework for their Surrealist practice. Strongly critical of conservatism and of the British presence in Egypt, they aligned themselves with “revolutionary, independent” art liberated from state interference, traditional values, and ideology—hewing to ideas articulated in a 1938 manifesto drafted by André Breton and Leon Trotsky at the Mexico City home of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera that called for an international front in defense of artistic freedom. While a part of this international community and in communication with the global network of Surrealists, the Cairo group was also of its place, incorporating local concerns and Egyptian motifs and symbols into their work.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

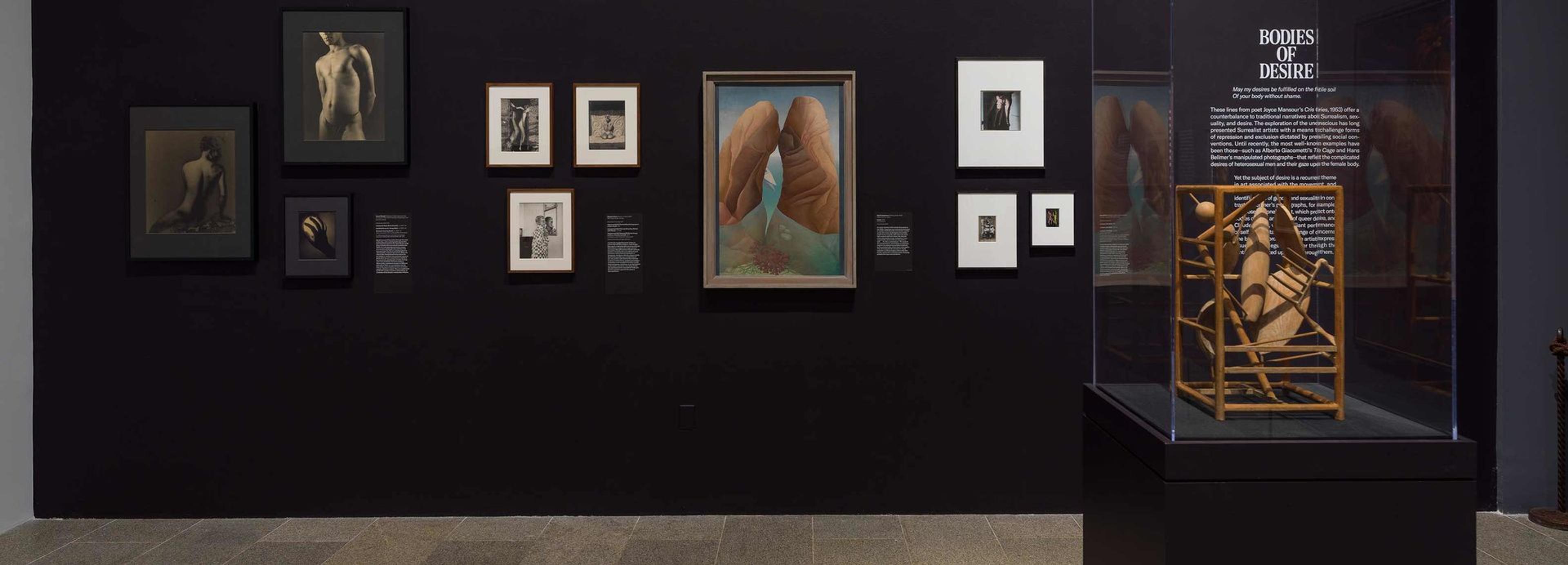

Bodies of Desire

These lines from poet Joyce Mansour’s Cris (Cries, 1953) offer a counterbalance to traditional narratives about Surrealism, sexuality, and desire. The exploration of the unconscious has long presented Surrealist artists with a means to challenge forms of repression and exclusion dictated by prevailing social conventions. Until recently, the most well-known examples have been those—such as Alberto Giacometti’s The Cage and Hans Bellmer’s manipulated photographs—that reflect the complicated desires of heterosexual men and their gaze upon the female body.

Yet the subject of desire is a recurrent theme in art associated with the movement, and Surrealism has encompassed more fluid identifications of gender and sexuality. In contrast to Bellmer’s photographs, for example, are those of Lionel Wendt, which project onto bodies of color an erotics of queer desire, and Claude Cahun, whose defiant performance of self-identity takes on a range of concerns. The bodies recorded by these artists express issues of privilege and power through the fantasies enacted upon and through them.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Cecilia Porras and Enrique Grau

Between 1954 and 1958, artists Cecilia Porras and Enrique Grau created experimental photographs set along Colombia’s Atlantic coast. While the two had no direct links with other Surrealist groups, they were aware of the movement. This knowledge came especially through émigrés from Europe, who reached American soil through Puerto Colombia, and it found form when Porras and Grau collaborated with a community of artists on the Surrealist film La langosta azul (The Blue Lobster) in 1954.

As a playful engagement with a new medium for the artists, the photographs can be read as sequels to their experiences while working on the film. They may also be seen as catalysts for exploring identity as well as the limits of expression under pressure. During the rule of General Gustavo Rojas Pinilla (1953–57), Colombia’s national art salon was suspended and the government systematically precluded demands for cultural renewal. On top of the prevalence of conservative social mores, this political shift drove artists and intellectuals to explore allegorical means of escape.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Haiti, Martinique, Cuba

The Caribbean islands have been both a convergence and a relay point for Surrealism. While the conventional history begins in 1941, with André Breton’s arrival in Martinique as a wartime refugee, Surrealism came to the Caribbean in multiple and concurrent waves—some arriving with newcomers, but many others generated by people who originated in the islands.

In Martinique, Surrealism took root in 1932, when a group of students including writer and theorist René Ménil produced the single-issue journal Légitime défense from Paris, proclaiming the Black self-affirmation movement of Négritude and attacking French colonialism. Ménil—as well as poets Aimé and Suzanne Césaire—carried the tenets of Surrealism to Fort-de-France. Their new journal, Tropiques, launched in April 1941 (the same month Breton arrived). Over its four years of publication, Tropiques promoted Surrealism as a critical tool to cast off colonial dependence and assert Martinique’s own cultural identity. Surrealism did not travel intact but flowed, fragmented and at times transformed—through the writings of Clément Magloire-Saint-Aude in Haiti and Juan Breá and Mary Low in Cuba, and in the art of both exiled Europeans (including Eugenio Granell and André Masson) and original inhabitants like Wifredo Lam and Hervé Télémaque—always focused on emancipatory freedom.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Eugenio Granell

Against a backdrop of political and social upheaval, Surrealism has intersected with the realities of displaced peoples, exiles, and those of various diasporas, as well as with the violent, hostile experiences of some who have engaged with the movement. Eugenio Granell is such a figure; in exile from Spain and moving within the Spanish-speaking Caribbean, he became a target of censorship and persecution at each new location. Granell remained, however, an energetic proponent of Surrealism, seeing in it “freedom for art—and as a consequence, freedom for mankind.”

Following the defeat of the Spanish Republic in 1939, Granell escaped to the Dominican Republic. During six years there, he worked as a symphony violinist, had his first exhibition, and formed lifelong friendships with André Breton and Wifredo Lam when they visited the island. In 1943, along with a group of poets, he launched the Surrealist journal La poesía sorprendida (Poetry Surprised). Under the increasingly authoritarian regime, however, Granell’s radical politics became untenable. Relocating to Guatemala in 1946, he connected with artists and intellectuals including the painter Carlos Mérida and the poet Luis Cardoza y Aragón. Threatened by opposing political forces, he then fled to Puerto Rico, where he remained until 1957, spurring a new interest in Surrealism there, particularly among university students.

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Automatism

In 1947 the literary world of Aleppo, Syria, saw the publication of a slim volume, Suryāl (Surreal), and with it the emergence of a dynamic cadre of poets and artists who embraced the technique of automatism, or unconscious creation. As poet Urkhan Muyassar explained, the group sought to free the “mysterious moments” of human creativity from a “superimposed” reasoning in order to get to repressed thoughts, or “what lies behind reality.”

Surrealist automatism represents—much like the harnessing of dreams—a way to unleash the mind and challenge the rationalism of the modern world. Unconscious creation, like doodling, has been a catalyst for an array of artists as they worked in related directions of improvisation and gestural abstraction. As seen in the examples here by André Masson and Joan Miró, it can capture the unguarded process of thought, bypassing the selectiveness and control of the conscious mind. Delicate compositions by Hans Arp and César Moro invite the hand of chance into production. Automatism has welcomed many inventive practices beyond line drawing, including Asger Jorn’s use of painters’ tools to scratch away the surface of a work and Oscar Domínguez’s surprise compositions made through decalcomania, a technique in which two painted surfaces are pressed together and then pulled apart.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

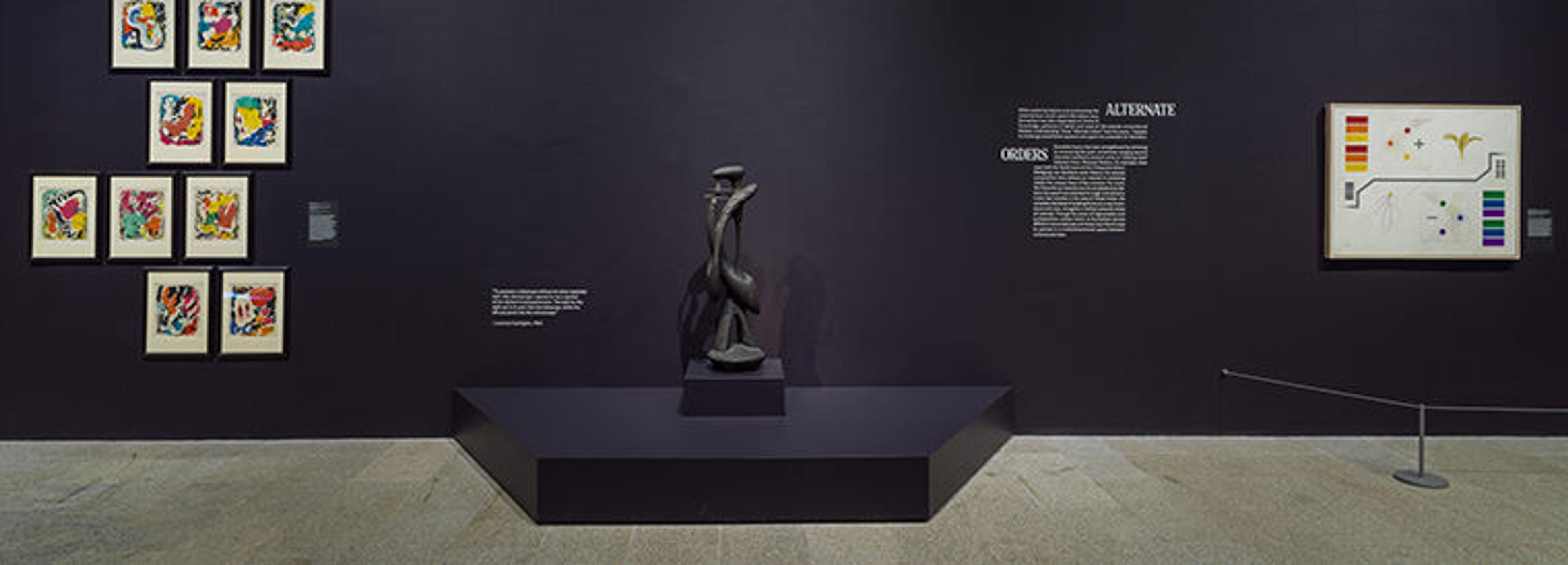

Alternate Orders

While exploring dreams and summoning the unconscious could upend the status quo, Surrealism has also depended on forms of knowledge, patterns of belief, and ways of life outside conventional Western understanding. These “alternate orders” have the power, if tapped, to challenge established systems and spark the potential for liberation.

Surrealist inquiry has been strengthened by retrieving or uncovering the past, sometimes merging several discrete traditions toward unity or holding itself between them. Kitawaki Noboru, for example, drew upon both the Taoist book of the I Ching and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s color theory; his precise composition here reflects an interest in rendering visible the unseen laws of the universe. For some, like Fernando de Azevedo and his ocultação (occultation), the search has extended to magic and alchemy. It also has included, in the case of Yüksel Arslan, the complete dismissal of existing forms as a way to produce one’s own, alongside a rarefied personal recipe of materials. Through the power of fragmentation and juxtaposition, artists drawn to Surrealism across different circumstances and times have found ways to operate in a multidimensional space between cultures and eras.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Eva Sulzer

For some artists associated with Surrealism, travel has brought the pleasure and freedom of experiencing lands not their own, cultures to which they did not belong, and peoples at first unfamiliar. Surrealists have negotiated such encounters with varying degrees of privilege and sensitivity. Eva Sulzer’s trips to the Pacific Northwest and to Mexico, and her resulting photographs, demonstrate a certain responsiveness and receptivity to these environments; her images record both the legacies of colonial violence and the resilience of Indigenous populations.

In 1939 Sulzer left Paris, where she had settled for nearly a decade, to travel with the artist couple Wolfgang Paalen and Alice Rahon. The three Europeans embraced the productivity of becoming unmoored from the familiar, and Sulzer recorded their experiences with her camera. She produced over three hundred images of the peoples and lands at sites in northwest Canada and in Alaska and Mexico. Many of her images would fuel the work of others in her circle: illustrating artist-archaeologist Miguel Covarrubias’s Spanish-language book on Indigenous art in North America (1945); spurring the poetry of César Moro and the work of a number of visual artists; and, most visibly, shaping the publication of Paalen’s dissident Surrealist journal, Dyn.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Mexico City

In Mexico City, as in other locations, taking up Surrealism meant grappling with the dual drives of internationalism and nationalism. While the poet Octavio Paz embraced the movement, others objected to it. The grand narrative murals of Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco had dominated the art scene since the Mexican Revolution. During the 1930s, however, the poets and artists of Los Contemporáneos (The Contemporaries), including María Izquierdo, distanced themselves from muralism and, along with Frida Kahlo, forged connections with Surrealism.

With its open-door policy, Mexico was a welcoming home to those fleeing totalitarian Europe. Including the political revolutionary Leon Trotsky (exiled from the Soviet Union), the circles around Kahlo and Rivera were internationalist, and it was through their encouragement that many Surrealists arrived in the capital city. Further attention came with the work of poet César Moro, who organized the 1940 Exposición internacional del surrealismo.

A core community of Surrealist artists who converged in Mexico City were women. In the particular case of Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington, their friendship involved the study of the region’s ancient cultures. Fed by archaeological, occult, and alchemical sources, these artists also infused Surrealism with feminism, magic, and nature.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

The Uncanny in the Everyday

“The only thing that fanatically attracts me,” wrote Jindřich Štyrský in Prague in 1935, “is searching for surreality hidden in everyday objects.” Indeed, at every corner, Surrealism can erupt with the uncanny, or a familiar sight made disconcerting and strange by the unexpected.

Alerted by Sigmund Freud’s work on the topic, artists associated with Surrealism in vastly different circumstances have tapped into the rich vein of estrangement embedded in the ordinary world. Photography proved particularly well suited to the project of recording the accidental coincidences, repetitions, and hazards of daily life. Brassaï and Manuel Alvarez Bravo, for example, captured surprising objects and scenes encountered through happenstance, while others, including Raoul Ubac and Dora Maar, turned away from such scenarios, instead manipulating or staging images to convey a sense of the uncanny.

With its potential to reveal hidden truths, the uncanny can take on aspects of satire and political subversion. To this end, photographic strategies of defamiliarization in works by artists in Belgrade, Bucharest, Cairo, Lisbon, Mexico City, Nagoya, Prague, Seoul, and other locations have guaranteed an ongoing questioning of power and society, even in the face of dire threats.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Chicago

In the 1960s Chicago became a convergence point of Surrealism as a form of radical protest. This was a moment of civil unrest and youth culture, marked by mass rioting in support of urgent causes, including the civil rights and workers’ movements, and campaigns against the protracted Vietnam War. An upsurge of activity came in August 1968, around the demonstrations aimed at influencing the Democratic National Convention, when national television captured the violent dispersal of protesters by Chicago police and National Guardsmen. The members of the Chicago Surrealist Group, under the leadership of Franklin and Penelope Rosemont, were both on the streets, narrowly avoiding injury and arrest, and behind the scenes, printing materials and supporting security efforts for activists.

The Chicago group’s prolific production of texts has become a hallmark of their radical Surrealism. In their early embrace of the mimeograph and offset-printing revolution of the underground press, the group has resiliently stayed in dialogue with current social movements, even as they drew inspiration from select historical examples of radicalism in art and politics, especially in earlier Surrealist groups. Working across generations, they have insisted on the inseparability of the politics of race, class, and gender in Surrealism.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Ted Joans

For the poet, musician, and artist Ted Joans, his very identity was shaped by travel and dislocation. To travel was to discard what he regarded as the artificial constraints of nationality, language, and culture—boundaries that could impose artificial, and sometimes violent, limits on freedom. He twice left the US in rejection of its endemic racism: once in the early 1960s, and again, about thirty years later, following the murder by police officers of Amadou Diallo, a young Black man in the Bronx. Joans discovered Surrealism as a boy, recognizing something “strangely familiar” in the pages of Paris-based journal Minotaure and other discarded publications that his aunt brought from the home of her white employers in Cairo, Illinois. “I chose Surrealism,” he explained, “when I was very young, before I even knew what it was. I felt there was a camaraderie like that which I found in jazz.”

He formally engaged with the Paris Surrealists after a chance meeting with André Breton in the French capital. His adage “Jazz is my religion, Surrealism is my point of view” reflects the free-form and itinerant lifestyle he adopted in his movement through North and Central America, North and West Africa, and Europe. While travel allowed freedom, it also provided community, as witnessed in his many collaborative works.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Revolution, First and Always

Revolution—Surrealism’s principal watchword—offers the possibility for transformation and liberation. Since its first pronouncement, Surrealism has mounted a challenge to predominant systems of power and privilege, division and exclusion, and has been emboldened by a growing chorus of voices. Alongside the profound cultural and sociopolitical forces that determined its own evolving history, Surrealism has presented a model for political engagement and agitation for artists, many of whom have been arrested as dangerous subversives. While Surrealist artists have sometimes expressed revolution in poetic terms, they have also aligned its tenets to collective action condemning the ills of imperialism, racism, authoritarianism, fascism, capitalism, greed, militarism, and other forms of control. From student-led protests in 1968 to protracted struggles for independence among formerly colonized peoples, Surrealism has served as a tool, but not a formula. As the Surrealist poet Léopold Senghor, the first president of Senegal and a cofounder of the Black consciousness movement Négritude, explained in 1960: “We accepted Surrealism as a means, but not as an end, as an ally, and not as a master.”

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.