Mary Sully: Native Modern

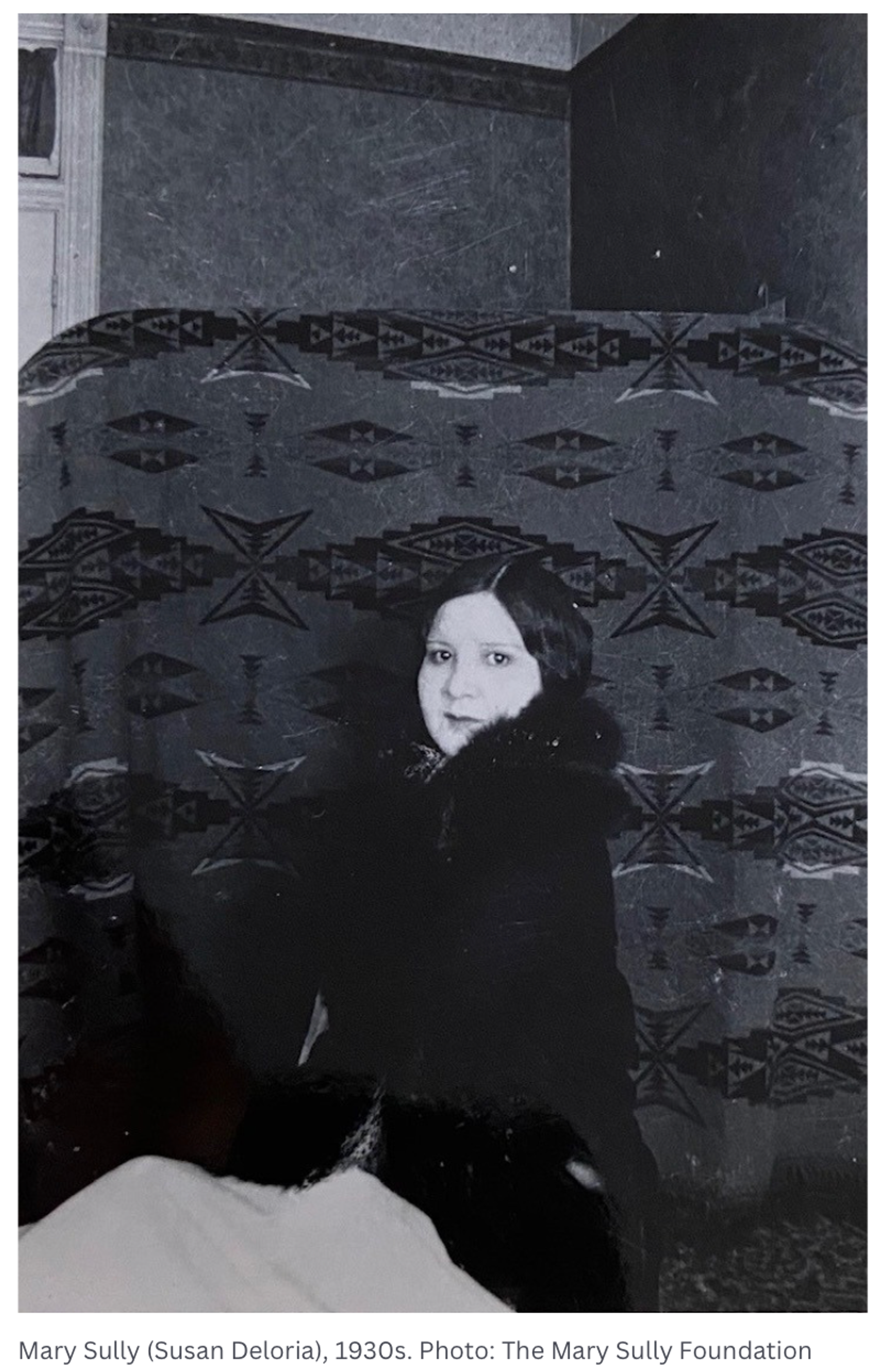

Born on the Standing Rock Reservation in South Dakota, Mary Sully (Yankton Dakota, 1896–1963) was a little-known, reclusive artist who, between the 1920s and the 1940s, created groundbreaking works informed by her Native American and settler ancestry. This first solo exhibition of her drawings features recent Met acquisitions and loans from the Mary Sully Foundation.

Working without patronage, in near obscurity, and largely self-taught, Sully produced some two hundred intricately designed and vividly colored drawings that complicate traditional notions of Native American and modern art. They mix meaningful aspects of her Dakota heritage with visual elements observed from other Native nations and the aesthetics of urban life. Euro-American celebrities from popular culture, politics, and religion inspired some of her most striking works, which she called “personality prints”—abstract portraits arranged as vertical triptychs. Together, they offer a fresh, complex lens through which to consider American art and life in the early twentieth century.

The exhibition is made possible by the Barrie A. and Deedee Wigmore Foundation.

Read, listen to, or watch stories about these works on The Met website:

Indian History

Three Stages of Indian History: Pre-Columbian Freedom, Reservation Fetters, the Bewildering Present

ca. 1920s–40s

Colored pencil, pastel crayon, ink, and graphite on paper

The Mary Sully Foundation

This work is one of Sully’s most ambitious, presenting an interpretive historiography of Indigenous experiences. The top panel depicts stratified scenes of precontact life and settler colonial violence—reservations and boarding schools as sites of assimilation and imprisonment. A gray, bleak reservation in winter contrasts with a lush green summer camp where women and children paint hides, enjoy a fire, and likely share memories; in summer, only select Dakota stories are told. In the middle panel graphite-colored barbed wires and brown human bodies merge with boldly painted parfleche, a beaded cradleboard, and regalia designs, creating layers of complex, rhythmic patterns. The bottom panel features multidirectional and brightly colored arrows that define past, present, and future generations as inextricable.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Native Themes

Sully traveled extensively with her sister, Ella Deloria, a linguistic ethnographer who trained with the pioneering anthropologist Franz Boas at Columbia University. Sully accompanied her sibling during both her fieldwork across the country and her academic studies. Together they documented in written and visual form—including several detailed “ethnographic” images—aspects of early twentieth-century life in the United States. Sully served as driver during these trips, and the sisters were confidantes and supporters of each other’s careers.

Exposure to reservations, rural communities, and urban settings afforded Sully a keen awareness of the distinct cultures among these sites. She closely observed the various aesthetic expressions of Native American communities and artists through beadwork, regalia making, textiles, leatherworking, and other mediums. Inspired by the richness and diversity of these artistic practices, Sully incorporated elements of them into her own visual art. Her drawings also refer to her close bond with her sister in the depictions of doubles and pairs of items worn or used by Dakota girls and women.

Lunt & Fontanne (Alfred Lunt, 1892–1977, and Lynn Louise Fontanne, 1887–1983)

ca. 1920s–40s

Colored pencil, wax crayon, ink, and graphite on paper

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Morris K. Jesup Fund and funds from various donors, 2023 (2023.312)

Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne were celebrated American stage and screen actors from the 1920s to the 1950s. They earned top billing as a husband-and-wife team and appeared, together and separately, in Broadway productions by some of the most famous playwrights of the day. Sully’s depiction of the celebrity couple includes a top panel with floral motifs and paired stars elevated by steps and platforms. The flower patterns are reconfigured in a complementary color palette in the middle panel, which emphasizes diamonds, zigzags, and triangular outlines. The bottom image, drawing on Plains Indian culture, presents two elaborately painted rawhide containers. They are thinly tied together, likely a reference to public speculation about the legitimacy of the actors’ marriage.

Timothy Cole (1852–1931)

ca. 1920s–40s

Colored pencil, wax crayon, ink, and graphite on paper

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Mary Sully Foundation, 2023 (2023.280.1)

This work celebrates the esteemed American wood engraver and illustrator Timothy Cole. The doubled profile faces of the “carved wood” on the top panel suggest an optical exercise known as Rubin’s Vase (developed by Danish psychologist Edgar Rubin in 1915). In this type of “bi-stable” imagery, forms—usually two profiles flanking a vase—share common borders;a viewer can focus on only one form at a time. The motif extends to the middle panel, where the faces are miniaturized into chain-like patterns, which then shift into stitched embellishments on a Native American–style fringed leather pouch at the bottom. In this way, Sully brings together three aesthetic practices—wood engraving, bi-stable imagery, and leatherwork—to explore the psychological intersections between subject and texture, figure and ground.

Jane Withers (1926–2021)

ca. 1920s–40s

Colored pencil, wax crayon, ink, and graphite on paper

The Mary Sully Foundation

Jane Withers rose to stardom as an American child actor portraying socially marginalized characters such as tomboys, orphans, and troubled youths in radio and film. Her edgy personality and dark braids were often contrasted with the sweetness and blonde ringlets of her costar Shirley Temple. In 1936 thenews that Withers had received kidnapping threats circulated widely in popular media andprobably captured Sully’s attention.

In her metaphorical portrayal of Withers, the artist tied a ribbon through a shady grove of trees surrounding a single sunflower standing tall—likely a gesture of safety and goodwill. The braided hairstyles of Dakota girls are a nod to the child actor’s on-screen look. Filled with sweetgrass and other plants, the brightly beaded hair ties carried fragrances of home and positive energy.

Alice

ca. 1920s–40s

Colored pencil, wax crayon, ink, and graphite on paper

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Morris K. Jesup Fund and funds from various donors, 2023 (2023.305)

This work cleverly deploys the turtle symbol in away that integrates Sully’s Dakota and settler heritage as well as her love for literature, film, and the imaginative world of childhood. In 1933 Paramount Pictures produced a popular film version of Lewis Carroll’s story Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, first published in 1865. Sully’s depictions of turtles—in an abstract pattern and as intricately beaded amulets—refer to both the Mock Turtle character in the tale and the “life charms” of Dakota girls. These protective charms—shaped as turtles for girls and lizards for boys—hold a child’s umbilicus so that they never lose their way, as Alice did in Carroll’s fantasies.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Social Themes

Raised in the Sioux Episcopal Church and the Brotherhood of Christian Unity—two cross-cultural religious organizations that emphasize community, charity, and support for older spiritual practices among Sioux reservations—Sully developed an awareness of social justice and Native American rights. The artist’s experiences in religious school and struggles with social interaction affected her perceptions of people and encouraged a fascination with world events, including the Great Depression, politics, and religion. She often engaged with these topics through popular media, film, music, and literature. Multiple drawings reflect her compassion for children and interest in how they are affected by family, class, or education, subjects informed by some of Sully’s own life experiences. Finding people and the communities in which she lived simultaneously invigorating and overwhelming, Sully articulated her observations from a socially removed position that allowed her to craft a distinctive, sensitive form of artistic expression.

Leap Year

ca. 1920s–40s

Colored pencil, wax crayon, ink, and graphite on paper

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Morris K. Jesup Fund and funds from various donors, 2023 (2023.313)

Subjects that involve romantic expectations—engagement, marriage, divorce—were of particular interest to Sully. These topics featured regularly in the popular magazines and newspapers she read, just as they do today. Media coverage of the Celtic tradition of women proposing to men on the extra day of a Leap Year, which occurred on February 29 of 1932, 1936, and 1940, likely prompted this piece. Amplifying the bright reds, yellows, and blues of painted parfleche imagery, Sully organized her composition as an aerial perspective on the glamorous hairstyles of women who competitively “fish for husbands” in a crowded pond. Eager to hook the biggest catch with the most dollar signs, the women overlook more accessible partners.

Children of the Divorced

ca. 1920s–40s

Colored pencil, wax crayon, ink, and graphite on paper

The Mary Sully Foundation

Sully expressed a sensitivity to social issues that affected children. Although her parents never divorced, members of her blended family had childhoods marked by the loss of a parent through death or long periods of separation when they were away at school. Possibly a response to a March 1934 Ladies’ Home Journal article titled “Children of Divorce,” this work presents a garden of flowers—chrysanthemums, daisies, roses, and tulips—budding and in full bloom. The blossoms in the top panel are each bisected into areas brightly lit and shadowed, their forms gradually abstracted as they rise. Sully applied design principles of complementary color, bilateral symmetry, and the Japanese concept of notan, or placement of light and dark, to organize her composition and communicate the complex realities of family life.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Personality Prints

The striking works that Sully called “personality prints”—vertical triptychs that make up the bulk of her dynamic drawings in colored pencil and ink on paper—reveal much about her lived experiences. She had a fascination with celebrities, an interest shared by many ofher contemporaries, including New York–based modernist painters and designers, and by her great-grandfather, the portrait painter Thomas Sully. She and her sister were avid fans of various forms of popular entertainment and attended many performances during their residencies in New York in the 1930s and 1940s. Sully also found artistic inspiration in images and stories from the Euro-American worlds of film, music, literature, and sports featured in magazines and on radio programs. Like her Dakota ancestors who worked with beads and quills, she translated her creative perspective on modern culture into a unique graphic language. Although Sully created her “personality prints” in relative isolation, they resonate with similar emblematic designs and images of the period, especially those that construct a sitter’s identity through related words and objects. To further explore these connections, look for paintings in The Met collection by Charles Demuth and Marsden Hartley in Galleries 902, 910, and 911 as well as textile designs by the Stehli Silks Corporation in Gallery 599.

Eugene Field (1850–1895)

ca. 1920s–40s

Colored pencil, wax crayon, ink, and graphite on paper

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Morris K. Jesup Fund and funds from various donors, 2023 (2023.308)

This is among Sully’s most distinctive “personality prints,” as it features two figural panels. The top pictures a group of children, in black silhouette, responding to an aural and visual sounding of colorful bells; in the middle, the motif of bells and profiles is abstracted in a dialogue between positive and negative space. The bottom panel, likely a drawing Sully produced to accompany her sister Ella Deloria’s ethnographic writing (possibly a book for children), shows a baby in a cradleboard near a Plains tipi. The writer Eugene Field is best remembered for his children’s poetry, such as “Wynken, Blynken, and Nod” and “Little Boy Blue.” Here, Sully appears to be referencing his “Why Do the Bells of Christmas Ring?,” which was widely read in the 1920s and 1930s. Field was profiled in a 1939 issue of Time magazine that Sully may have encountered.

JT (Julia)

ca. 1920s–40s

Colored pencil, pastel crayon, ink, and graphite on paper

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Morris K. Jesup Fund and funds from various donors, 2023 (2023.310)

The “Julia” of this portrait remains unidentified. The organic patterns of the red-spotted green cactus leaves, grapes, tulips, and other flowers in the three panels create a kaleidoscopic design that evokes the geometric abstraction of Plains Indian women’s creations.

Babe Ruth (1895–1948)

ca. 1920s–40s

Colored pencil, wax crayon, ink, and graphite on paper

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Morris K. Jesup Fund and funds from various donors, 2023 (2023.306)

Sully’s work represents the star athlete George Herman “Babe” Ruth in spare, dynamic form, with panels suggesting an artfully fractured baseball diamond as well as his personal flair. Ruth began his career, in 1914, as a pitcher and out fielder with the Baltimore Orioles, but it was with the New York Yankees that he secured his reputation as a powerful slugger, becoming the most famous (and highest-paid) athlete in the United States during the 1920s. Ruth’s larger-than-life personality made him especially newsworthy through the 1930s, and he is credited with establishing baseball as the dominant national sport of its time.

The Architect (Ralph Adams Cram, 1863–1942)

ca. 1920s–40s

Colored pencil, pastel crayon, ink, and graphite on paper

The Mary Sully Foundation

Sully’s composition blends the representational dynamism of urban architecture—in the top panel viewed as a concentric skyline—with abstract rhythms of geometric Native design. During The Met conservation of this vibrant triptych, an inscription by the artist was discovered that identifies the subject as Ralph Adams Cram—a leading architect of churches and colleges in the neo-Gothic style in early-twentieth-century America. Cram may have been familiar to Sully through their shared Episcopalian faith, which, along with Dakota culture and aesthetics, was a central reference point for her art. In the years that Sully lived on the Upper West Side, near Columbia University, Cram was overseeing the construction of the neighboring Cathedral of Saint John the Divine. A mammoth undertaking that occupied him from 1916 until his death in 1942, the cathedral remains unfinished today.

Fiorello La Guardia (1882–1947)

ca. 1920s–40s

Colored pencil, wax crayon, ink, and graphite on paper

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of The Mary Sully Foundation, 2023 (2023.280.2)

This work reveals Sully’s admiration for Fiorello La Guardia—the mayor of New York City from 1934 to 1945—known for his charismatic personality and commitment to civic reform. It revolves around designs of crowns and densely drawn flowers, a reference to his Italian first name, which translates as “little flower.” During three terms leading the city through the Great Depression and World War II, La Guardia unified the transit system; expanded construction of public housing, playgrounds, parks, and airports; reorganized the New York Police Department; and implemented federal New Deal programs. As a socialist member of the Republican party, he also curbed the powerful Democratic Tammany Hallpolitical machine. A highly visible national figure, La Guardia—like his close ally President Franklin D. Roosevelt—harnessed radio to expand his influence.

Gertrude Stein (1874–1946)

ca. 1920s–40s

Colored pencil, pastel crayon, ink, and graphite on paper

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Morris K. Jesup Fund and funds from various donors, 2023 (2023.315)

One of Sully’s characteristic vertical triptychs, this work features a repeating rose motif that references a line of poetry by the avant-garde writer Gertrude Stein: “Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.” As in Stein’s verse, Sully’s flower is both literal and symbolic. The compositional dialogue between positive and negative space in all three panels echoes aspects of Dakota women’s arts. Stein’s cultural profile heightened in 1934 during her thirty-seven-city lecture tour of the United States—marketed as the expatriate’s homecoming—to promote her memoir, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933), which became her most commercially and critically successful book.

Fred Astaire (1899–1987)

ca. 1920s–40s

Colored pencil, wax crayon, ink, and graphite on paper

The Mary Sully Foundation

Fred Astaire—regarded by some as the greatest popular dancer of all time—began his long career in stage, film, and television in 1905. After moving from the vaudeville circuit in New York to London’s West End, in 1933 he made his debut in Hollywood, where he launched a popular partnership with dancer Ginger Rogers and became a staple of film musicals, such as Top Hat (1935). Astaire, who shared Sully’s Episcopalian faith, inspired one of her most kinetic tributes. The colorful triptych features Art Deco–like patterns around a central motif that echoes the dizzying speed of his tap-dancing feet.

Ziegfeld (Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr., 1867–1932)

ca. 1920s–40s

Colored pencil, pastel crayon, ink, and graphite on paper

The Mary Sully Foundation

The Broadway impresario Florenz Ziegfeld is best known for his innovative theatrical revues, the Ziegfeld Follies, which ran from 1907 to 1931. These extravaganzas featured elaborate costumes and sets as well as young women chorus dancers who performed synchronized choreography. Sully’s homage may have been inspired by the 1936 motion picture The Great Ziegfeld. The production won numerous Academy Awards, including Best Dance Direction for “A Pretty Girl Is Like a Melody,” one of the most famous musical sequences in film history. Sully evoked that opulent number inthe kaleidoscopic top panel of this triptych: radiating circles of women’s faces are framed by a star and flanked by stage curtains, with the balding heads of male audience members below.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.