Introduction

Friends, rivals, and, at times, antagonists, Édouard Manet (1832–1883) and Edgar Degas (1834–1917) forged one of the most significant dialogues in nineteenth-century art. Their groundbreaking bodies of work would have been vastly different, if not unthinkable, without the creative exchanges that punctuated their careers from the time of their meeting in the early 1860s. Examining their paintings, drawings, and prints in direct juxtaposition for the first time, this exhibition not only highlights the intersections of their artistic production but also reveals the contrasts, conflicts, and divergent paths that shaped modern art from its origins.

Manet and Degas were born just two years apart, both the eldest sons of Parisian upper-middle-class families, yet their differing temperaments led to strikingly distinct styles, political views, career strategies, and approaches to different media. Although they rarely worked side by side, each took stock of the other’s work, distilling it until it became foundational for his own project or, perhaps just as interesting, never integrating it at all. Given the scarce primary evidence of their complex relationship, direct comparison of their works is even more crucial, allowing us to assess how these giants of French painting defined themselves with and against each other.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

An Enigmatic Relationship

1. An Enigmatic Relationship

Hear about the origins of Manet and Degas’s relationship

NARRATOR:

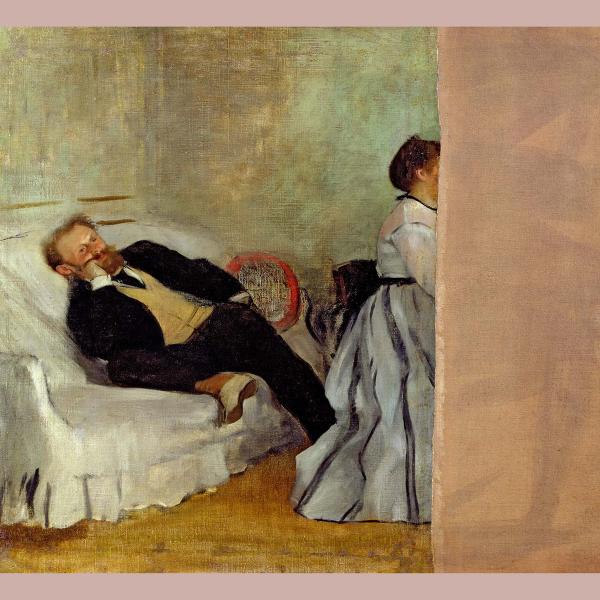

It was an evening like many others. Suzanne Manet played the piano while her husband Édouard reclined on the sofa, lost in reverie. But this particular evening would be immortalized by their friend Edgar Degas, who, with his talent for total recall, would go home and paint the scene as a gift for the young couple.

What happened next has confounded historians for the last 150 years.

STEPHAN WOLOHOJIAN:

Degas later recounts getting to the apartment and seeing the right part of the painting quite violently slashed in a clear cut that cropped the face of Mrs. Manet off.

NARRATOR:

What precipitated this abrupt shift in Manet and Degas’s relationship? Perhaps we can find a clue in their first meeting, less than a decade before, in the galleries of the Louvre.

Manet was thirty-two, Degas thirty. Both, rebellious sons of bourgeois families. And they were among the first generations of artists to avail themselves of a comparatively recent invention—the museum. For artists who had previously studied black-and-white reproductions, the experience of seeing the actual works was a revelation. Here’s Stephan Wolohojian, John Pope-Hennessy Curator of European Paintings, and Ashley Dunn, Associate Curator of Drawings and Prints. They’re co-curators of the exhibition Manet/Degas.

STEPHAN WOLOHOJIAN:

They could see history in color. The Louvre became a training ground that could in many ways even substitute for the traditional classroom experiences of the Academy.

ASHLEY DUNN:

Degas was standing in the Louvre in front of a painting attributed at the time to Velázquez of the Infanta Margarita Teresa. So, he’s holding a copper plate that would have been covered in a waxy kind of ground and using a needle to draw into that wax, thereby revealing the metal underneath. It was unusual to make an etching outside of the studio. And Manet made a remark along the lines of, “How bold of you to etch directly in front of the motif without any kind of preparatory drawing!”

NARRATOR:

That very etching is featured later in the exhibition alongside one by Manet, after the same painting. We don’t know exactly when Manet made his etching. And whether it was before or after Degas made his colors how we might imagine their exchange.

STEPHAN WOLOHOJIAN:

Manet had already made some pretty major steps on the artistic front when this meeting occurred. Degas was slower to come into being as an artist. So, it’s an interesting moment to imagine a senior artistic figure looking over the shoulder of this more junior one, even though they were contemporaries and in contemporaneous ways exploring the world around them.

NARRATOR:

Manet and Degas would continue to push each other to take the risks that would define their careers. But they left little evidence of their relationship in their papers. For example, though Degas speaks of Manet in his many letters to others, none of his letters is addressed to Manet. And for his part, Manet left just a few letters to Degas.

ASHLEY DUNN:

One of the visual testaments of their relationship, though, is this wonderful series of drawn portraits that Degas made of Manet. He made around ten drawings of him. That is in stark contrast to the fact that we have no clear representations of Degas by Manet. There’s the possibility that he appears in the corner of a racing picture from behind, but we cannot be certain.

STEPHAN WOLOHOJIAN:

I’m glad you mentioned that, because there may not be letters, but there is a paper trail, literally, and a very moving and rather extraordinary series of drawings that capture Manet in different moments, in different frames of mind, truly evocative of the kind of familiarity that just doesn’t come with casual observation.

NARRATOR:

Like Degas’s painting of Manet lost in reverie—the painting that Manet so violently slashed. Scholars and others have speculated that Manet was dissatisfied with the way that Degas painted the profile of Suzanne and that he may have painted his own portrait of her as a corrective.

ASHLEY DUNN:

In an early red chalk drawing of Suzanne the profile is repeated very insistently. It gives you the sense that there was maybe a degree of obsession about getting that profile right.

STEPHAN WOLOHOJIAN:

Outraged that his friend would have defaced—literally—his painting that way, Degas apparently grabbed it and took it back.

How many of us have had a moment in a friendship or in any relationship where you just sit back, and you say this is it? This is the great moment, just the way that evening must have been, and how often those moments are fractured or broken and are completely irreparable. They can’t be mended together, or if they can, they’re always mended and never whole.

NARRATOR:

Keep listening as we explore Manet and Degas’s enigmatic relationship, through an unprecedented exploration of the artists’ work, exhibited side by side.

This audio feature is sponsored by Bloomberg Philanthropies, produced in collaboration with Acoustiguide.

Attempts to assess the relationship between Manet and Degas are complicated by the sparse record of their exchanges. Their first meeting is impossible to date precisely, and hardly any correspondence between them remains. A fuller picture emerges from remarks they made about each other—equally admiring and critical—in their letters to mutual friends, as well as from the commentaries of contemporaries and early biographers. The writer George Moore described their friendship as one “jarred by an inevitable rivalry.” Their artwork reveals a conspicuous asymmetry: While no clearly identifiable representations of Degas by Manet are known to exist, a group of striking portraits—drawings, etchings, and a painting—offers a glimpse of Degas’s regard for his close colleague.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Artistic Origins: Study, Copy, Create

Both Manet and Degas circumvented the established training ground of the École des Beaux-Arts to learn their craft, perhaps signaling from the outset their shared desire for independence. An essential aspect of their formation was copying works of great European artists of the past found in the collections of the Louvre Museum and the print room of the National Library. Indeed, according to their early twentieth-century biographers, the two artists met for the first time in a gallery at the Louvre, where Degas was busy making an etching of a painting attributed to Diego Velázquez.

Their family backgrounds and social status afforded them the opportunity to further enrich their artistic educations through travel. Both visited Italy several times in the 1850s, and Manet ventured to Holland and Central Europe as well. Closer to home, they most admired the works of Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres and Eugène Delacroix. These and other models shaped the development of their own visual languages. Their references to the art of the past ranged from quotation to homage to stylistic imitation.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Family Origins and Tensions

Born in Paris two years apart, Manet and Degas were the eldest sons of wealthy bourgeois families. Manet’s father was a senior civil servant and his mother, a diplomat’s daughter, was goddaughter of the king of Sweden. Degas belonged to a family of bankers and businessmen based in Paris, Naples, and New Orleans. After attending prestigious schools, both abandoned the studies in law expected for men of their class and instead followed artistic paths that their fathers initially opposed.

Each artist turned to portraiture as he launched his career and found willing subjects among family members. One of Manet’s most frequent sitters, besides his wife, Suzanne, was her son Léon, whose paternity is unclear but whom the painter treated with fatherly affection. Degas, who remained a bachelor, created psychologically complex portraits of his siblings and his Italian relatives that reveal tensions in their relationships.

The families of the two artists often interacted and socialized together: Degas’s father held musical evenings at his apartment on Mondays, which the Manets attended; Manet’s mother hosted a salon on Thursdays that Degas regularly joined. In 1867 Léon was given a job at Degas’s family’s business.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Challenging Genres at the Salon

2. Shocking Subjects and Modern Paris

How did each artist respond to the demands and expectations of the Salon?

NARRATOR:

In the 1860s, Paris was booming. Slums were being cleared for majestic, tree-lined boulevards and lush parks. Sewers no longer drained into the Seine. A consumer class was growing, with department stores to serve them, stocked with knockoffs of the latest fashions and factory-madegloves. And for those with means, the opera, cafés, and the racetrack—an import from England—were the places to be seen. But there was one institution that was resistant to change. And both Manet and Degas wanted to shake it up.

ASHLEY DUNN:

The Salon was a state-sponsored exhibition that was the primary proving ground for any artist at the time, one of the few places where contemporary artists could show their work.

STEPHAN WOLOHOJIAN:

They were events like the Whitney Biennial every other year here in New York.

NARRATOR:

When Manet met Degas, making that etching in the Louvre, he had already debuted at the Salon with two paintings, one of which had earned an honorable mention. But his next submission, Déjeuner sur l’herbe, which depicted a naked woman picnicking with fully clothed men, was rejected on grounds of obscenity. Two years later, Manet returned to the Salon with the even more confrontational Olympia.

ASHLEY DUNN:

Olympia was scandalous because, like with the Déjeuner sur l’herbe, Manet presents us with a female nude who has no guise of mythology. She is a contemporary woman, a model named Victorine Meurent, and she is shown as a courtesan, and she has a direct gaze out at the viewer, and her gaze places the spectator in the position of patron.

NARRATOR:

Manet borrows this composition from a piece called Venus of Urbino by the artist Titian. That painting similarly shows a nude woman lying on a bed.

ASHLEY DUNN:

The Venus of Urbino has a dog at the foot of her bed, whereas in Olympia we have a cat, who’s sort of on alert, arched back, tail up, also reacting to the presence of the viewer.

NARRATOR:

In both Manet and Titian’s paintings, there is a maid in the background. But in Manet’s painting, that woman is a Black person—

ASHLEY DUNN:

A model named Laure.

NARRATOR:

—another signal that Manet’s is a contemporary work.

STEPHAN WOLOHOJIAN:

One of the fascinating things about Manet is he makes these grand statements at the Salon, these incredibly bold statements. And then when the scathing criticism comes in, he’s a big crybaby. He’s writing to Degas, he’s complaining to all his friends: “Repairing to the countryside. Can’t handle Paris.” He’s attracted to the flame, and then when he gets singed, he recoils, but he plays the establishment in a much more engaging way than to just reject it outright and forge a separate collective…

ASHLEY DUNN:

But he does continue to seek that official—

STEPHAN WOLOHOJIAN:

—right—

ASHLEY DUNN:

—recognition even though he’s critical of it as he writes articles advocating for reform of the jury, and in certain cases when things are rejected from the Salon, he elects to show them in a shop window instead. But he, nevertheless, continues to submit to the Salon right up until the end.

STEPHAN WOLOHOJIAN:

This is very different from the stage that Degas eventually embraced, which were these series of Impressionist exhibitions.

ASHLEY DUNN:

Well, I don’t think he would have used that label exactly because that was applied by a critic and wasn’t really adopted until later. He would describe that group as maybe New Realists. They were a group of independents. There was power to that collective, but it was a very eclectic group.

NARRATOR:

Critics couldn’t take their eyes off Olympia’s in-your-face nudity—but perhaps Degas—who had finally gotten into the Salon himself that year—was looking at the flowers.

STEPHAN WOLOHOJIAN:

One of the wonderful things to contemplate is Degas’s response. Olympia in some ways is a quartet of the central figure of Olympia, the attendant maid, the cat, but then at its center this extraordinary, lush bouquet. And Degas’s next painting is an extraordinary portrait of this massive bouquet with a figure next to it.

NARRATOR:

In an art world in which categories were inviolable—one painted a still life or a portrait—A Woman Seated beside a Vase of Flowers (Madame Paul Valpinçon) depicts its ostensible subject off to the side and cropped at the shoulder, upstaged by the flowers, front and center. This was a bold, radical move on Degas’s part.

STEPHAN WOLOHOJIAN:

The woman with the vaseis one of the most jarring and provocative pictures in that it makes you question whether it’s still life, whether it’s a portrait, whether it’s some other kind of painting. Its sort of threshold in those different categories is what makes it so powerful and so modern.

NARRATOR:

Degas’s Salon painting, a Scene of War in the Middle Ages, garnered little notice. But Woman Seated beside a Vase of Flowers marked a bold new direction. He would never look back again.

In the 1860s, the essential proving ground and public stage for emerging artists was the Salon, the official juried exhibition of paintings, sculptures, and works on paper held by the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Before a robust system of commercial galleries developed, the Salon was the main forum for attracting the attention of critics and collectors. It also facilitated government patronage through purchases and awards.

A codified hierarchy of categories, or genres, set expectations about appropriate subjects and relative scale, with monumental history painting considered the pinnacle. Manet’s early Salon submissions boldly transgressed traditional boundaries. Degas initially spent years trying to produce an ambitious history painting, but after 1865—when his Scene of War in the Middle Ages went unnoticed while Manet’s Olympia caused a sensation—he altered his course.

Manet remained loyal to the Salon, submitting works every year. When faced with rejection, he sought alternative venues, displaying paintings in private galleries, shop windows, and his studio. Degas exhibited annually at the Salon until 1870, before abandoning it to establish independent exhibitions with fellow artists who later became known as the Impressionists.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Beyond Portraiture

3. The Social World of Manet and Degas

Explore the artists’ portraiture practices and shared social circle

NARRATOR:

If you were to visit Degas in his home or the Café de la Nouvelle-Athènes on a Sunday evening, you might find Edouard Manet or Edgar Degas holding court over a group of writers and artists arguing the burning question of the day: How should the arts reflect the rapidly changing world? And in their homes and studios, these men sat for Degas and Manet in portraits that are extraordinarily revealing. Marni Kessler, Professor of Art History at the University of Kansas, is particularly taken with Manet’s portrait of the novelist Émile Zola.

MARNI KESSLER:

He’s holding a book, but you see his fingers holding the page, so there’s this idea that he’s been interrupted. Manet wants to convey a sense of immediacy here.

NARRATOR:

Immediate, yes—but staged. Manet has dressed the set with objects that represent their shared interests—and a reproduction of the painting that brought them together.

MARNI KESSLER:

There’s a grisaille version of the Olympia that one could look at and imagine might be a photograph. But he averts Olympia’s eyes so that they look toward Zola. One of the ways of understanding that is when it was exhibited, it was Émile Zola who publicly wrote in a positive way, and Manet even includes the cover of the brochure that Zola wrote.

NARRATOR:

Manet also includes a Japanese screen and a woodblock print.

MARNI KESSLER:

Japanese objects were flooding the European shores. These artists were interested in the subject matter: people engaging in daily life activities, but these artists also appreciated the eccentric angles, perspectives from above, rushing perspectives. Space was not constructed in a way that was necessarily logical, but rather there was an emphasis on seeing things in new ways. And that’s of course what these artists were trying to do.

NARRATOR:

Degas’s portrait of the artist James Tissot similarly shows Tissot sitting in his studio—but here he’s leaning back in his chair with the look that says, “Get on with it already.” Behind him on the wall, in a witty bit of staging, is a copy of a Northern Renaissance portrait, and above it, a Japanese-style painting. But in Degas’s portrait of Tissot, we also see the influence of Japanese art on Degas.

MARNI KESSLER:

We see him from one of Degas’s wonderful angles, from above. He liked to assume a viewpoint that was really kind of impossible unless you were sort of a fly on the wall [laughs] looking down onto the figure. And the dramatic tilt of the floor further accentuates that unstable viewpoint. As he does for The Dance, for example, or Milliners, he assumes these viewpoints that allows him to include information we would not normally see if we confronted the subject head on.

NARRATOR:

But these “bohemians,” as they called themselves, also gathered privately. And if you were lucky to get an invitation to the homes of the Manet or the Morisot families, you might hear the composer Jules Massenet playing his new piano piece or Charles Baudelaire and Émile Zola discussing the impact of the urban environment on the human soul. And in the center of it all was the Morisot family’s middle daughter: Berthe.

MARNI KESSLER:

Manet and Morisot met through the artist Fantin-Latour at the Louvre. He was very interested in her and wanted her to model for him.

NARRATOR:

Twenty-seven-year-old Berthe Morisot wasn’t just a member of a prominent family; she was an up-and-coming artist whose work was regularly shown at the Salon, an extraordinary achievement for a woman at that time.

MARNI KESSLER:

She was one of the founding members of the Impressionist group. But she’s also come to us through Manet’s eleven portraits of her.

They deeply influenced each other. He looked at her work, she looked at his work, and you can really see that back and forth between them. That said, he never sat for her, and he never represents her as an artist.

NARRATOR:

Manet’s portraits give us a window into a growing intimacy between these two artists, one married, the other refusing a bevy of suitors so that she might focus on her work.

MARNI KESSLER:

There’s an increasing familiarity and a kind of removal of context. These portraits become increasingly complicated and troubling. The terrain of the paint becomes worked over, thickened, and really complex.

His last portrait of her is typically referred to as Berthe Morisot in Mourning. She is in mourning for her father who had recently died, but we also see represented in the very matière, in the very material of the paint, Manet’s own sense of impending mourning as she is about to marry his brother.

NARRATOR:

Interestingly, Degas eventually acquired this painting for his collection.

Was Manet in love with Berthe? Or was he mourning the loss of an intimate friendship?

MARNI KESSLER:

The painting is, for lack of a better word, disturbing. She looks skeletal. The surface of her face is composed of very sort of aggressive brushwork. Her eyes are reduced to these dabs of black paint. And he will paint her up until the point when she marries his brother, and then he will never paint her again.

There’s another work that he paints of her with a bouquet of violets at the base of her neckline, and her hair is in disarray. Violets were flowers that were exchanged between lovers or very close friends. He made three different prints based upon it, and in one of them he alters her pose. That print is just astonishing, and it has a kind of violence to it.

NARRATOR:

Manet and Degas’s portraits of their friends are revealing—but not just of their subjects.

MARNI KESSLER:

I think it’s important to remember that the creation of a portrait is an encounter between two people. It is a kind of looking back and forth. It is a looking at each other.

Portraiture was in vogue in France during the mid-nineteenth century and occupied an important place in the work of Manet and Degas. Neither relied on commissions, freeing them to focus primarily on family, friends, and public figures connected to their social and artistic circles. Both artists stretched the definition of portraiture, introducing ambiguities and exploring its narrative possibilities by representing a broad range of people, from members of high society to stage performers and women of the demimonde.

Manet imbued his models with a certain stateliness. He presented them full-length, often in static poses, and magnified their presence by having them directly address the viewer. Degas was equally concerned with the expressive power of bodies and faces. He aimed to convey something of his sitters’ characters and psyches by depicting them in distinctive, unconventional postures within familiar environments.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

The Morisot Circle

In the summer of 1868, Manet was introduced to the sisters Berthe and Edma Morisot, both painters, by their mutual friend the artist Henri Fantin-Latour. Like Manet’s first encounter with Degas, the meeting occurred at the Louvre Museum. The Manet and Morisot families soon became close and invited each other to their weekly salons, which Degas also attended.

The portraits that Manet and Degas made of the Morisots vividly capture this intimate social circle. Letters between the Morisot family members also provide key insights into Manet and Degas’s relationship. For instance, following the quarrel over Manet slashing a painting that Degas had given him, the sisters’ mother wrote to Berthe: “The Manets and M. Degas are playing host to one another. It seemed to me that they had patched things up.”

In 1874 Berthe joined the Manet family, marrying Édouard’s younger brother Eugène. That same year, she participated with Degas in what became known as the first Impressionist exhibition. She would later support Degas’s efforts to collect works by Manet.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

At the Racecourse

Horse racing, which had arrived from England at the end of the eighteenth century, became an increasingly popular pastime for Parisians with the inauguration of new racetracks at Longchamp and Vincennes on the outskirts of the city. As a glamorous milieu with high stakes, thrilling competition, arresting speed, and diverse crowds, the racecourse appealed to artists who sought to depict scenes of contemporary life. Degas was quick to recognize its modernity, creating his first racing pictures in the early 1860s and submitting a large canvas on the subject to the Salon of 1866.

A drawing by Degas reveals that the two artists spent time at the racecourse together. They both treated the subject repeatedly in a pictorial dialogue that continued into the 1870s. Degas’s compositions capture a distinct moment in the sport: he favored the seconds before the start, the subtle and suspenseful choreography of the mounts champing at the bit. Manet’s scenes, on the other hand, are all gallop, visual explosion, and acceleration.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

From One War to Another

4. Degas in New Orleans

Hear about Degas’s time spent in New Orleans

VOICE ACTOR READING AS EDGAR DEGAS:

Mon cher Tissot, que dites vous de cet en-tête? C’est le papier de la maison. Ici on ne parle que coton et change.

My dear Tissot, what do you think of this letterhead? It’s the house stationery. Here we only talk about cotton and the exchange.

NARRATOR:

Edgar Degas had arrived in New Orleans to see for the first time the source of his family’s fortune—American cotton. Under Manet’s influence, he had abandoned history painting, turning to contemporary subjects, like the racetrack. And what could be more contemporary than the commodity that had led to the American Civil War? Michelle Foa, associate professor of art history at Tulane University.

MICHELLE FOA:

Degas’s visit to New Orleans in late 1872, early ’73, took place several years after the end of the Civil War. His mother had been born in New Orleans. Degas’s two brothers, René and Achille, founded a firm called the De Gas Brothers, and they worked as buyers of cotton on behalf of French merchants, their uncle was what was known as a factor, who worked on behalf of southern planters. And it is with his uncle, Michel, and his uncle’s three daughters and their families, that Degas lived during his four-and-a-half-month stay in New Orleans.

EDGAR DEGAS:

Des villas à colonnes…peintes en blanc, dans des jar-dins de magnolias, d’orangers, de bananiers…des enfants pâles et frais dans des bras noirs, des chars…trainés par un mulet…voilà un peu de couleur local…avec une lumière éblouissante et dont mes yeux se plaignent.

Villas with columns painted in white, nestled in gardens lined with magnolias, orange trees or banana trees… pale and pristine-looking children wrapped in black arms, chariots pulled by mules… these are the local colors… all under a blinding light that torments my eyes.

MICHELLE FOA:

It’s hard to imagine that the artist had been ignorant of the racial oppression that pervaded in New Orleans after the war. But the only Black labor he did acknowledge was that of Black women taking care of white children.

EDGAR DEGAS:

Aprés avoir perdu du temps en famille à vouloir y faire des portraits dans les plus mauvaises conditions de jour que j’aie encore trouvées et ima-ginées, je me suis attelé à un assez fort tableau…Intérieur d’un bureau d’acheteurs de coton à la Nouvelle Orléans.

After wasting time with my family, wanting to make portraits in the worst possible conditions I have ever encountered and imagined, I set about working on a rather hard painting… inside a cotton buyers’ office in New Orleans.

NARRATOR:

Here, Degas illustrates his relatives doing a variety of things in the interior of his uncle’s cotton buyers’ office on Carondelet Street.

MICHELLE FOA:

In the foreground is his uncle, Michel Musson, and it is his cotton factoring firm. He has a tuft of cotton in his hands, and he is assessing the properties of the fibers. You have René, who is the figure reading the newspaper; Achille is leaning back slightly against that window frame. And then there’s yet one more relative, kind of half-seated against the long wooden table covered in cotton. That is the husband of one of Degas’s cousins, William Bell. There’s a customer, and one presumes that William Bell, with his hands full of cotton, is encouraging that potential buyer to perform the same kind of assessment that we see Michel performing in the foreground.

NARRATOR:

This was a world Degas had never seen up close—one that had once been reliant on enslaved labor and now depended on exploited sharecroppers. And his American relatives intended to keep it that way.

MICHELLE FOA:

Surprisingly, after the war, his uncle had been a supporter of a short-lived movement called the Louisiana Unification Movement, which promoted the integration of public schools and transportation. That movement quickly faltered. Not long thereafter, Michel Musson and William Bell became members of an anti-Reconstruction, white supremacist group called the White League.

NARRATOR:

What did Degas think of all this? He doesn’t tell us in his letters. But unlike Manet, who was deeply involved in the politics of the day, Degas avoided explicitly political subjects in his painting. The exploitation that made his family’s business possible goes unremarked as well, but he had come to New Orleans in search of something.

MICHELLE FOA:

His trip to New Orleans is often written about as a kind of search for his maternal origins. But I think he’s also interested in origins of a material sort. Prior to the Civil War, about ninety percent of French cotton originated in the American South. Thanks to the expansion of sharecropping in the United States, by the end of the 1870s, France is importing even more cotton from the southern United States than it was before the war.

NARRATOR:

When Degas returned home, he would make that connection explicit.

MICHELLE FOA:

When Degas exhibited the Cotton Office in the 1876 Impressionist exhibition, he surrounded it by several of his laundress pictures, and that’s another way in which Degas is trying to connect the intimate relationship between southern cotton and French textiles.

EDGAR DEGAS:

Il y a à Manchester un riche filateur, Cottrell, qui a une galerie considérable. Voilà un gaillard qui me conviendrait…

There is a wealthy cotton spinner in Manchester, named Cottrell, who owns a very impressive gallery. Here’s a fellow who would meet my needs well.

MICHELLE FOA:

He did not succeed in selling it to a British merchant as he initially envisioned, but he did sell it in 1878 to the Museum of Fine Arts in Pau. It was the very first work by an Impressionist to enter a French museum collection.

NARRATOR:

And by 1878 Degas sorely needed the money.

MICHELLE FOA:

The artist’s uncle, the artist’s brother, and the artist’s father all heavily invested in Confederate bonds, much to their financial detriment, which—along with other financial strains the family was facing—actually created significant hardship for the artist long after the war was over. And so, the effects of his family’s financial investment, not to say ideological investment, in the Confederacy was felt by the artist for years and years after.

Manet regularly produced works based on events that touched or outraged him as a citizen, while Degas shied away from current events in his public work. Early in the artists’ relationship, the United States was torn apart by the Civil War (1861–65) and political maneuvers in Mexico led to the execution of Emperor Maximilian (1867), both subjects that Manet depicted.

The Franco-Prussian War (1870−71) drew the two men closer together. While many artists fled Paris, Manet and Degas stayed to defend their city as members of the National Guard. The visual trace of these conflicts is more subtle in Degas’s work, whereas Manet produced some of his boldest prints in response to the conditions of war and its aftermath.

The U.S. Civil War directly affected Degas’s family. His mother was from New Orleans, and he had relatives who were enslavers, supported the Confederacy, and continued to make their living from the cotton trade. In the autumn of 1872, Degas made his first visit to the city. He mentioned Manet several times in letters home.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Impressionisms

Beginning in 1874, Degas played a leading role in organizing the independent, nonjuried shows that later became known as the Impressionist exhibitions. In a letter that year, he lamented, “Manet still refuses to join us.” Although popularly considered a leader of the movement, Manet never exhibited among their ranks, preferring instead to submit his work to the official Salon.

While Degas considered these exhibitions an opportunity to showcase Realist art, characterized by direct observation of modern life, the Impressionists quickly became associated with an interest in capturing ephemeral moments and the transitory effects of light, especially through painting en plein air, or outdoors. Like their Impressionist colleagues, Manet and Degas experimented with brighter palettes and more visible brushwork, but both artists preferred to paint in their studios. As the work in this gallery attests, they were equally attuned to the commercial demand for seascapes, but Manet went further in adopting scenes of outdoor leisure as his subject matter.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Overlapping Networks

Manet and Degas’s interwoven social networks included not only fellow artists but also poets, novelists, and journalists. In the 1870s they gathered regularly at Paris cafés for lively discussion and debate. The portraits the two artists produced during this period depict many of the same café habitués, such as the painter-printmaker Marcellin Desboutin and the Irish writer George Moore, as well as the art critics—Stéphane Mallarmé and Edmond Duranty in particular—who were their crucial champions.

Manet would have been considered the more literary of the two, establishing close relationships with the great French authors of the day: Charles Baudelaire, Émile Zola, and Mallarmé, among others. These associations are evident especially in his portraiture. Degas’s early paintings display a profound interest in literature, but his work did not reveal personal connections until the 1870s, when he exhibited penetrating portraits of the incisive art critics Duranty and Diego Martelli. Ironically, while the artists increasingly tried to liberate themselves from institutional structures and to assert their independence, their worlds intertwined more and more with critics, dealers, and other influential players in the art world and press.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Parisiennes

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the cafés, shops, music halls, theaters, and ballets of Paris attracted artists and writers as spaces where diverse crowds intermingled. Drawing on the spectacle of these popular venues, Manet and Degas depicted working women and individual performers, casting different social types—expressed through dress and deportment—in their scenes. They took equal interest in stars and their audiences, shopkeepers and clients.

The two poles of labor and leisure, as represented by Parisian women, underpinned the artists’ individual formulations of the “New Painting,” as critic Edmond Duranty termed the Realism and Impressionism of the 1870s. Though Manet and Degas explored these overlapping themes in tandem, each approached them in his own way. Their method of working, however, remained consistent: although they aimed to convey the spontaneity and immediacy of everyday life, their paintings were carefully contrived and executed in the studio.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Liminal Gaze

Responding to the work of earlier Realists, such as Gustave Courbet, and influenced by photography, Manet and Degas dismissed the ideal academic nude and reinvented the subject for their own time. The female nude became the subject of their most daring works, from Manet’s Olympia to Degas’s monotypes and late pastels. Eschewing traditional notions of beauty, the artists rendered bodies with unprecedented frankness while candidly presenting the sexual commodification of female nudity in their day.

The two artists’ works convey differing gender dynamics. Whether alone or with men, the women in Manet’s paintings express a certain self-possession through their pose and gaze, whereas Degas frequently crafted scenes fraught with tension and ambiguity.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Degas After Manet

5. Degas's Collection of Manet

What might Degas’s personal collection of Manet’s work reveal to us?

NARRATOR:

If you were to visit Edgar Degas in his home on the Rue Victor Massé in the Montmartre section of Paris towards the end of the nineteenth century, you would enter a bare parlor with a circle of easels, each displaying a painting by Delacroix, Ingres, and other masters of the previous generation. And hidden away, there was a painting in four pieces. Ann Dumas, curator at the Royal Academy of Arts in London and consultant curator at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston.

ANN DUMAS:

The Execution of the Emperor Maximilian is really one of Manet’s great paintings. It’s actually the second of four versions that Manet made. So, it seems that after Manet’s death in 1883, his family cut this large canvas up, with the intention of selling them as separate individual works of art. It’s an indication, I think, about how deeply Degas cared about this painting, that he went to considerable pains to track down as many of the fragments as he could.

NARRATOR:

Degas, once the aspiring history painter, even traded some of his own work to assemble Manet’s great history painting, which depicts Emperor Maximilian of Mexico, a puppet of Napoleon III, facing a firing squad after being abandoned by the French following a Mexican uprising.

ANN DUMAS:

Manet was outraged. And he decided that this subject needed to be treated as a work of art on an epic scale. So, in some ways, he’s looking back to the example of old master history painting. But the way that he’s treated the subject is very modern, very contemporary, and I think one of the reasons Degas found this composition so compelling is because of the informality of the grouping of the figures, particularly the soldier who’s looking down at his rifle as he’s loading the ammunition. It’s exactly that kind of thing that Degas does. That sort of informal, unobserved gesture is something that comes up again and again—you know, a ballet dancer tying a ribbon of her shoe or something like that.

NARRATOR:

And if you were to venture upstairs to Degas’s private quarters, you would see another fragment of a painting—Degas’s painting of Manet and his wife—the very one that Manet had taken a knife to.

ANN DUMAS:

He never got rid of it. There’s a fascinating photograph that Degas took of himself with his friend, a sculptor called Bartholomé, in Degas’s apartment.

NARRATOR:

On that wall behind Degas and Bartholomé is one of Manet’s great still lifes, The Ham. Marni Kessler, in her recent book Discomfort Food: The Culinary Imagination in Late Nineteenth-Century French Art, makes a provocative argument as to why it’s there.

MARNI KESSLER:

At the École des Beaux-Arts, artists learned about the internal anatomy of the human body. And so I link Manet’s painting of the ham to drawings from anatomy books, and see it not just as porcine flesh, but Suzanne’s missing body, her missing flesh. And we also know that when he moved to another apartment, he hung The Ham and the portrait of the Manets beside each other in his bedroom.

ANN DUMAS:

We have to remember that Degas had quite an acerbic wit [laughs]. And so, I think that this might have amused him to hang these two works together.

NARRATOR:

There’s another object in that photograph that may have significance—an empty chair.

MARNI KESSLER:

That empty chair is so poignant because it holds for me a reference to those early drawings that Degas made of Manet seated in a chair. There is no reason to include an empty chair, but he does.

NARRATOR:

Upstairs, one could find other mementos of an enduring influence.

STEPHAN WOLOHOJIAN:

Entering in the vestibule of his private space was a copy of Manet’s Olympia by the young painter Gauguin. Not quite full scale, but it’s large, and it reminds us that Gauguin would have had the opportunity to copy Manet just the way Manet and Degas had the opportunity to copy Titian’s work.

NARRATOR:

The artist Monet started a subscription to raise enough money to keep Olympia in France, to place it in the public space of the Musée du Luxembourg.

ASHLEY DUNN:

And Degas of course contributed to that public subscription—

STEPHAN WOLOHOJIAN:

—modestly—

ASHLEY DUNN:

—modestly.

ASHLEY DUNN AND STEPHAN WOLOHOJIAN:

[Laugh]

NARRATOR:

When Manet died in 1883 at the age of fifty-one, Degas had only a few prints by Manet in his collection. But he would go on to acquire eight paintings, along with drawings and an almost complete set of prints.

In 1912, Jacques-Émile Blanche published a quote reportedly spoken by Degas at Manet’s funeral: “He was greater than we thought.”

ANN DUMAS:

I think Manet and Degas had quite a complicated relationship. But I think that Degas was very affected by Manet’s death. Because he lived surrounded in his apartment and studio in Paris with all these works by Manet that he’d collected, he was living with Manet’s presence on a daily basis.

NARRATOR:

Degas would continue to make art for nearly three decades, but he lost interest in public exhibition, growing increasingly reclusive. Perhaps, as he modeled a ballerina in wax around a metal armature, he reflected on how the balance between himself and Manet had shifted over the years. No longer was he the young unknown to Manet’s up-and-comer, aspiring to the Salon while Manet got all the press. He was in museums now and had lived to see Manet’s work acquired by museums. He had lived long enough to have his work criticized as being out of step. And as the burgeoning modernity that he and Manet had depicted wrought automobiles, electric streetcars, and moving pictures, his eyesight faded, as he retreated into his memories.

Shaken by Manet’s premature death in 1883, Degas reportedly declared at the time of his friend’s funeral, “He was greater than we thought.” Degas took an active part in various commemorations that brought together their artistic circle, including a memorial banquet in 1885 and the subscription launched by Claude Monet in 1890 to acquire Olympia for the French state.

Degas’s lasting admiration for Manet is most evident in his personal art collection, which he had at one time envisioned turning into a museum. Among works by El Greco, Ingres, Delacroix, and others, those by Manet occupied a prominent place in his holdings. By 1897 Degas had acquired nearly eighty works by Manet, including eight paintings, over a dozen drawings, and an almost complete set of prints. In handwritten notes, Degas detailed how he managed to collect them through gifts, purchases, and even exchanges for his own works. His perseverance enabled him to reunite several of the dispersed fragments of one of Manet’s most ambitious paintings: The Execution of Maximilian.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.