Jadine Collingwood, Curatorial Fellow, Visual Arts, Walker Art Center

Siah Armajani recalls a childhood game he played with his classmates as they walked home from school. Wandering through the streets of Tehran, they would trace their path along the city walls, enjoining their peers to "follow this line." Covering significant moments in the artist's life and career, as well as important events that have inspired his thinking, this chronology asks readers to follow the line of Armajani's reflections on democracy, anarchy, architecture, technology, and philosophy.

Construction begins on Monticello, the home and plantation that Thomas Jefferson would design and build outside Charlottesville, Virginia.

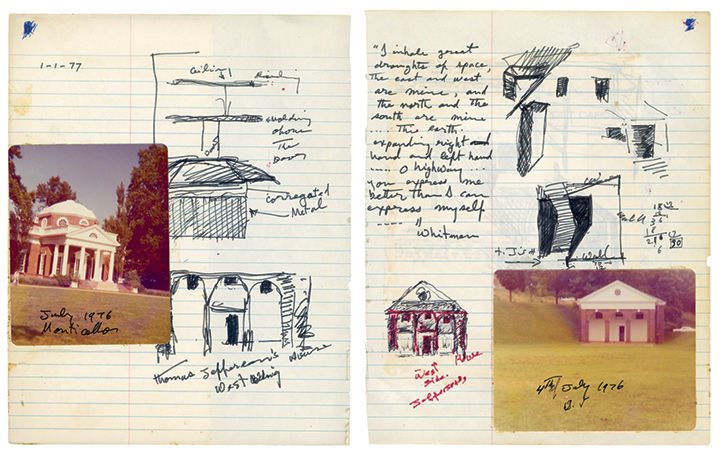

Pages from the artist's notebook with photographs and sketches of Thomas Jefferson's Monticello, 1976–1977.

In 1976 Armajani visits Monticello and begins a series of works that investigate and deconstruct Jefferson's attempt to develop a democratic architectural style. In addition to the main house, the artist references the "west wing" and "east wing" of the complex, the unseen subterranean service areas that housed Jefferson's slaves.

The artist in his studio constructing Thomas Jefferson's House: West Wing, Sunset House (1977).

Subsequent works continue to reference Monticello, including Irene Hixon Whitney Bridge (1988) in Minneapolis, painted "Jefferson yellow."

The Italian anarchist Luigi Galleani publishes the newsletter Cronaca sovversiva in Barre, Vermont, an immigrant community of quarry workers. The publication advocates the use of violence to overthrow tyrants and existing government institutions. Galleani's followers, known as the Galleanisti, carry out a wave of bombings and assassination attempts in the United States.

In the 1990s Armajani begins a series of gazebos dedicated to various anarchists active in the United States, including Luigi Galleani.

The Iranian Constitutional Revolution leads to the establishment of a parliament aimed at limiting the power of the shah. Under the cover of night, revolutionaries distribute antiestablishment statements known as shab-nameh, or night letters.

The Italian-born American anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti are convicted of first-degree murder in connection with an armed robbery of the Slater and Morrill Shoe Company in Braintree, Massachusetts. After a series of appeals Sacco and Vanzetti are sentenced to death and executed by electric chair on August 23, 1927.

During the trial prosecutors focus on the defendants' political activities and their status as immigrants to portray them as un-American outsiders. In a contemporaneous account published in the Atlantic Monthly, Felix Frankfurter, then a professor at Harvard Law School, described the travesty of the trial: "Outside the courtroom the Red hysteria was rampant; it was allowed to dominate within. The prosecutor systematically played on the feelings of the jury by exploiting the unpatriotic and despised beliefs of Sacco and Vanzetti, and the judge allowed him thus to divert and pervert the jury's mind. . . . By systematic exploitation of the defendants' alien blood, their imperfect knowledge of English, their unpopular social views, and their opposition to the war, the District Attorney invoked against them a riot of political passion and patriotic sentiment; and the trial judge connived at—one had almost written, cooperated in—the process."[1] As details of the trial and the men's suspected innocence become known, the case draws widespread attention and galvanizes protests around the world.

Armajani recalls the early impact of a painting of Sacco and Vanzetti reproduced in a newspaper: "When I was in Iran in high school, I saw Ben Shahn's painting of Sacco and Vanzetti handcuffed together and it touched me; they were very intelligent people; they were calling on America to redeem the promises of freedom of expression, education, work; that is why they joined the anarchist group."[2]

The German Expressionist architect Erich Mendelsohn visits Buffalo, New York, to photograph the city's iconic grain elevators. On returning to Germany he publishes the photographs, along with images of American cityscapes and other industrial sites, in his book Amerika: Bilderbuch eines Architekten (1925), which inspires the industrial aesthetic of European modernist architects.

Throughout his career Armajani analyzes and interprets the experience of American vernacular architecture. The artist explains: "My immediate architectural environment was farmhouses, barns, grain elevators, silos and so on. The peculiar quality of these structures is that once you walk inside and around them you know exactly how and why they were put together. Everything is self-evident. Erich Mendelsohn and Le Corbusier were also fascinated by rural American architecture; these structures were precursors to the Modern movement. So I started taking pieces from these buildings and putting them together. It was a nonfunctional architecture that retained the appearance and statement of architecture.[3]

Alexander Rodchenko presents his design for a workers' club in the Soviet pavilion at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris. Organized around a central reading table, the spare design emphasizes function over bourgeois comfort.

In the late 1970s Armajani begins a series of utilitarian reading rooms intended for public use. Made from simple materials such as plywood, these works recall Rodchenko's self-evident and unadorned designs.

Siah Armajani is born in Tehran, Iran. His father is Aga Kahn Armajani, a successful merchant, and his mother is Taj-Saltanat Bahrami.

Attends the Mehr Presbyterian missionary school in Tehran. Armajani recalls the early influence of Mrs. Doolittle, a grade-school teacher who introduced him to liberation theology.

At age seven Armajani decides to become an artist. His father arranges for him to study with a master painter and calligrapher. "He was terrifying," Armajani recalls. "The first day, he produced a couple of semi-rotten apples in a dish, gave me ink and brushes, and told me to paint them. After a few weeks, he told me that I had no talent whatsoever and that he was taking me only as a favor to my father, and he used to strike me on the hands with a long ruler when I made a mistake. I studied with him for only six months—I couldn't stand it any longer—but in the end I really could draw."[4]

Martin Heidegger presents his lecture "Bauen Wohnen Denken" ("Building Dwelling Thinking") to the Darmstadt Symposium on Man and Space. He argues that thinking about the relationship between building and dwelling advances thought on the nature of being. Establishing that "dwelling is the manner in which mortals are on Earth," Heidegger asserts that "we do not dwell because we have built, but we build and have built because we dwell, that is, because we are dwellers."[5] This proposition reimagines the relation between humans and things: if the Cartesian axiom "I think therefore I am" envisions being solely as a function of the mind (thinking), Heidegger conceives of being in connection to the spaces we inhabit (dwelling).

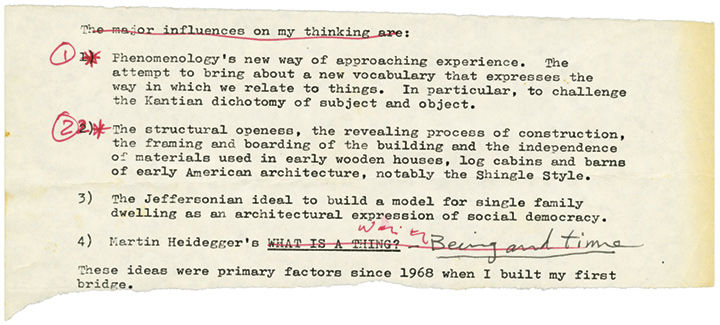

Page from Armajani's notebook.

Noting the philosopher's influence, Armajani writes, "My work, to a great extent, [has] been conditioned by Martin Heidegger's thoughts who made good easy and bad difficult."[6]

Iran's democratically elected prime minister, Mohammad Mossadegh, is overthrown in a coup orchestrated by the United Kingdom and the United States, strengthening the monarchical rule of the shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

A youthful supporter of Mossadegh, Armajani starts to participate in the student movements that oppose the shah.

"My interest in politics was ignited by my grandmother Soghora, who was a cousin to Mirza Kouchek Khan Jangle. In my grandmother's youth Kouchek Kahn was under siege in a rural province and my grandmother and her friends brought food and substance to aid his group and help keep morale strong. Her stories of being in danger of losing her life on a daily basis during this period were extremely influential to me."[7] At the time Soghora was only fourteen years old.

After the 1953 coup, pro-democratic protesters revive the practice of distributing political messages via night letters.

In Tehran Armajani begins producing the works that he classifies as belonging to his Persian period; he continues with this body of work after his move to the United States, completing it in 1964. It includes the Night Letters, text- and image-based works that contain political slogans like "oil belongs to us" and "independence belongs to us."

The Soviet Union launches Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite, into orbit, galvanizing the Cold War space race with the United States. Armajani closely follows the space effort.

As a student at the University of Tehran, Armajani takes classes in Western philosophy and becomes familiar with works by various philosophers, from Socrates to the German school of Hegel, Nietzsche, and Heidegger.

At the insistence of his father, Armajani leaves Iran, escorted by an armed guard onto an airplane. The artist immigrates to the United States and settles in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Creates Letters Home, a work made by stitching together letters to his family in Iran describing his first impressions of the United States.

Attends Macalester College in St. Paul, where his uncle Yahya Armajani, a graduate of Princeton University, is professor and chair of the history department. The artist takes several art courses and becomes familiar with the work of American Abstract Expressionist painters:

"[My teacher] had a tray of Ab-Ex slides, I would go to his office and pull out one at a time and I could not figure out how anyone could think that way, I was so amused, it was beyond comprehension."[8]

As a student Armajani writes a paper on the Russian Constructivists for his European art history course. He recalls, "I was interested in the Constructivists because they were political, because there was no separation between the citizen and the artist—what we're trying to do now in public art. They are really our paradigm, Tatlin and Rodchenko and Malevich and the rest"[9]

Exhibits Prayer (1962) and Prayer for the Sun (1962) in the Biennial of Painting and Sculpture at the Walker Art Center.

The Walker purchases Prayer for its permanent collection, becoming the first institution to acquire Armajani's work.

The Saqqakhaneh group forms in Iran. A loose collective of artists, the group combines modernism with traditional content derived from folk culture, Shi'ite art, calligraphy, and decorative motifs. Although Armajani is already in the United States, Saqqakhaneh artists cite his work as a major influence.

Graduates from Macalester with a major in philosophy. Immediately after graduating, Armajani rents a cheap loft above a pizza parlor on Nicollet Avenue in Minneapolis and begins working as an artist.

The Warren Commission presents its findings to President Lyndon B. Johnson, concluding that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone in the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

Completes a text-based work titled Warren Report the following year; the work includes scientific books unrelated to the assassination, challenging the authoritative tone of texts published in the wake of the report.

Founding of the National Endowment for the Arts; this federal program establishes an Art in Public Places fund to support public art projects.

The University of Minnesota receives a NASA-sponsored grant to establish a space and science research center on its campus. The center houses the Hybrid Computer Laboratory, which contains one of the few computers in the country capable of processing both analog and digital systems.

Through an informal relationship, Armajani works with the lab's director, Stephen Kahne, to realize several projects.

Marries Macalester classmate Barbara Bauer.

Robert Venturi publishes Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, described by the architect as a "gentle manifesto" for a "nonstraightforward architecture."[10] The book establishes the terms for a post-modern architecture premised on ambiguity, tension, and difficult unity.

In 1978 Armajani explained, "I am strongly influenced by Robert Venturi's writings, especially his Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. His perspective on American social democracy is very important because it incorporates political, social and economic considerations. It is the attitude of inclusion, not exclusion."[11]

In 1970 the artist creates a bridge named for Venturi.

Letter from Siah Armajani to Martin Friedman, director of the Walker Art Center, 1962.

Becomes an American citizen.

Creates Idea Bridge, a conceptual drawing that diagrams the artist's study of iconic bridge systems, including the George Washington Bridge, spanning the Hudson River, and the Victoria Falls Bridge, in Zambia. Small illustrations compare various wooden truss systems used in early American bridge design; these studies inform Armajani's subsequent bridge works.

The engineers Billy Klüver and Fred Waldhauer and the artists Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Whitman establish Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), which fosters collaborations between artists and engineers.

Armajani travels to New York City to meet with E.A.T. members, and his colleague Alan Shepp founds a regional chapter, E.A.T. Minneapolis. Although, as Armajani recalls, little comes out of the regional E.A.T. group, the artist continues to reach out to local scientists on his own.

Takes night classes at the Control Data Institute in Minneapolis, where he learns the computer-programming language Fortran.

Builds First Bridge in White Bear Lake, Minnesota. In a play with depth and perception, the height of the bridge gradually tapers to four feet from its ten-foot-high entrance.

The rural community of Jackson, Minnesota, invites Armajani to help revitalize buildings along its main street. He collaborates with city officials and residents to devise a proposal to restore commercial storefronts and redevelop the downtown area. The artist also works with students and faculty from the local vocational school to produce a study of the area's architectural history and conduct interviews with local business owners to determine the most cost-effective method to restore each building.

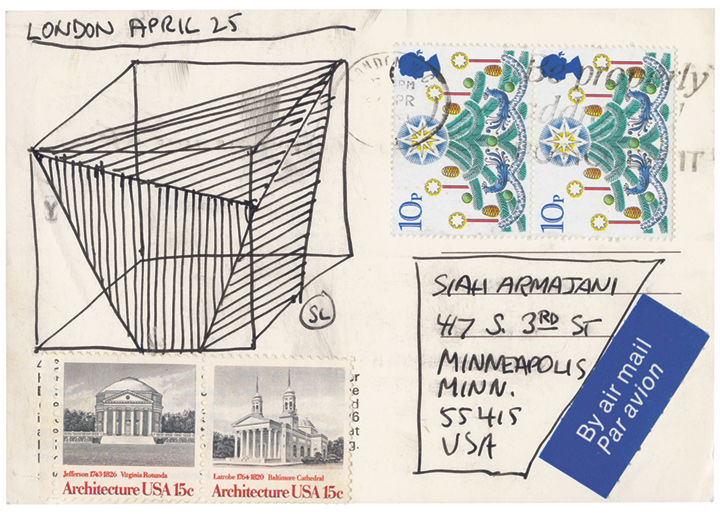

Postcard from Sol LeWitt to Armajani with stamp showing the rotunda designed by Thomas Jefferson for the University of Virginia.

Teaches at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. There Armajani meets fellow artist Barry Le Va, who introduces him to the work of Joseph Kosuth, Sol LeWitt, Lawrence Weiner, and other New York conceptual artists.

Compiles "Manifesto: Public Sculpture in the Context of American Democracy." In twenty-six points Armajani outlines his approach to public art, demanding that work be "open, available, useful and common."

Exhibits A Fairly Large Number in Art by Telephone at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. For this conceptually driven exhibition, artists are asked to communicate an idea for an artwork to the show's curator over the telephone. Museum staff execute each work according to the artist's oral instructions.

NASA scientist Jerome Pearson presents his proposal to colleagues to build a "space elevator" that would stretch from earth to outer space. In the same year Armajani develops A Fairly Tall Tower, a proposal for a 48,000-mile-high tower extending from the earth to space.

On July 20, 1969, the Apollo 11 lunar module successfully lands on the moon; the astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin become the first humans to step onto the surface of the moon.

To create the work Moon Landing, Armajani purchases a new television set and turns it on during the lunar landing. After the astronauts return to earth, the artist turns off the TV and locks the plug. He inscribes the screen with the words "This T.V. set has witnessed the Apollo 11 Mission" and hand-traces pages from the New York Times with the headline "Men Walk on the Moon."

Works with holography pioneer Tung H. Jeong to develop Ghost Tower, a proposal for a holographic tower projected above First National Bank in Minneapolis.

Exhibits A Number between Zero and One and North Dakota Tower in Information at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, a seminal group exhibition of conceptual art. Armajani's contribution to the show, derived from a printout of the number 10-205,714,079, recalls Sol LeWitt's maxim "the idea becomes a machine that makes the art."[12] The structure is nine feet tall.

Exhibits Bridge over Tree in the exhibition 9 Artists / 9 Spaces at the Walker Art Center. Featuring nine works in public spaces, the exhibition is plagued by a number of difficulties, including the vandalism, removal, or confiscation of several works.

While Armajani's contribution elicits little controversy, the installation of the work in a field near the Walker encounters its own complications. As the bridge is off-loaded from a flatbed truck, it falls to the ground, and the night before the show's opening, the pine tree under the bridge turns brown. Environmentalists had threatened to burn down the bridge if the tree died, so curator Richard Koshalek spray-paints it green to give it a livelier appearance.

Collaborates with scientists at the Hybrid Computer Laboratory at the University of Minnesota to make a number of computer-based works. During this time Armajani makes his first films using a CDC 1700, a 16-bit minicomputer capable of plotting time-lapse drawings onto 16mm film.

Armajani's Fifth Element (1971) as installed in the exhibition Works for New Spaces at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, May 18–July 25, 1971.

Works with Stephen Kahne at the University of Minnesota and the ElectroCraft Corporation in Hopkins, Minnesota, to develop Fifth Element, a metal column that, supported by a hidden electromagnet, appears to float in space. The work is exhibited in the group show Works for New Spaces at the Walker Art Center. Also included in the exhibition are works by Larry Bell, Lynda Benglis, Dan Flavin, Robert Irwin, and Donald Judd.

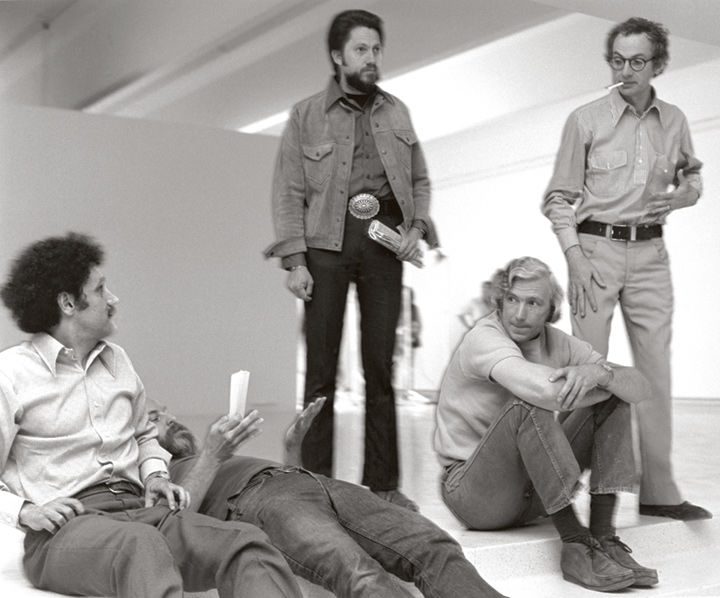

Siah Armajani (far left) and Martin Friedman (far right) during the exhibition Works for New Spaces at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, May 18–July 25, 1971.

Begins work on Dictionary for Building (1974–1975), a series of more than one thousand cardboard models. Each model focuses on a discrete architectural component—such as a door, window, or staircase—shown in isolation or put into relation with another element. The artist explains, "I was trying to put together an index of art and architectural possibilities, all the physical properties of doors, windows, and so forth, such as a chair against a wall, or a chair by a window."[13]

Rather than generic units, the models connect to actual memories of moving through space. "Everything in Dictionary for Building I've seen in actual life; I've experienced it in actual life. I saw a door at the top of stairs; I saw a door to the basement; I saw a door to the first floor, second floor. I saw doors in many shapes and forms. . . . I did not make anything up, everything is documented."[14]

On the fiftieth anniversary of the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti, Massachusetts governor Michael Dukakis issues a proclamation stating that the men had been unfairly tried and convicted.

Ten years later Armajani constructs Sacco and Vanzetti Reading Room #1, shown in 1987 at the Kunsthalle Basel as part of the artist's first European retrospective.

The artist installing Thomas Jefferson's House: West Wing, Sunset House (1977), part of the group exhibition Scale and Environment: 10 Sculptors, at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, October 2–November 27, 1977.

Installs Thomas Jefferson's House: West Wing, Sunset House, included in the exhibition Scale and Environment at the Walker Art Center.

Iranian Revolution: demonstrations against the shah commence in 1977, developing into a series of strikes and protests. The shah flees into exile in January 1979, and the cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini returns from exile to lead the new Islamic Republic.

Installs Lissitzky's Neighborhood in the rotunda of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, for the exhibition Young American Artists.

Builds Reading House for the 1980 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, New York. In an inversion of the conventional building process, the shape of the house was dictated by the furniture, which was built first and positioned to receive ideal daylight.

Armajani cultivates his public art practice, developing a number of outdoor communal spaces, including Meeting Garden (1980) for Artpark in Lewiston, New York. The work includes a quotation from John Dewey's Art as Experience (1934): "As long as art is the beauty parlor of civilization, neither art nor civilization is secure."[15]

Armajani creates a number of the Dictionary for Building models as large-scale sculptures.

Installs Employee Lounge at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC. The work includes text from Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass (1855). Museum employees use the space for the duration of the exhibition Metaphor: New Projects by Contemporary Sculptors.

Receives honorary doctorate of fine arts from Macalester College.

Designs Louis Kahn Lecture Room at the Fleisher Art Memorial in Philadelphia.

Designs a number of public works, including Poetry Lounge at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena and NOAA Bridge in Seattle.

Begins work on the Elements series, a group of thirty full-scale sculptures that reference architectural details and furniture. In contrast to the open-ended compositions of the Dictionary for Building sculptures, the series is described by the artist as "closed, self-sufficient, self-defining."[16]

Iran-Contra affair: Reagan administration officials secretly arrange to sell American weapons to the Iranian government in order to secure the release of US hostages and fund the Contras, a paramilitary group fighting the Sandinista government in Nicaragua, triggering a political scandal.

Begins collaborating with the architect Cesar Pelli, the artist Scott Burton, and the landscape architect M. Paul Friedberg to design Battery Park City Plaza in New York, completed in 1988.

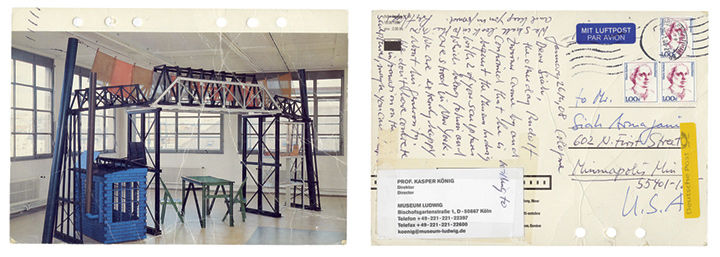

Front and back of postcard to Siah Armajani from Kasper König, curator of Skulptur Projekte Münster, featuring one of the artist's Elements sculptures.

Participates in Skulptur Projekte Münster. Designs Study Garden for the outdoor spaces of the Geologisches Museum of the University of Münster. Armajani also creates a model for the unrealized Münster Pedestrian Bridge.

Designs Irene Hixon Whitney Bridge, a 375-foot structure covering sixteen lanes of highway that connects Loring Park to the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden. The bridge features a commissioned poem by John Ashbery.

After receiving the commission, Armajani visits the soon-to-be demolished Hennepin Avenue Bridge (built 1888–1891), which spans the Mississippi River. With hopes of incorporating one of the bridge's steel arches into his design, he makes several preparatory studies. Ultimately the bridge's massive scale proves far too monumental for his design.

Works again with the architect Cesar Pelli on a proposal for the Yerba Buena Tower in San Francisco. In their remarks Armajani and Pelli emphasize the collaborative nature of their project: "One thing that this is not, this is not a sculpture on a building. This is one building from the ground until the very tip of the building top. The building top is an element of the architecture like the colonnade at the base, but much more so."[17]

Revises "Manifesto: Public Sculpture in the Context of American Democracy."

Awarded an honorary doctorate of fine art from the Atlanta College of Art.

Muhammad Ali lights the Olympic flame on the artist's sculpture Bridge, Tower, Cauldron, commissioned for the Summer Olympics in Atlanta.

Begins a series of glass works that take as their point of departure the German writer Paul Scheerbart's Glasarchitektur (1914), a treatise that attributes utopian possibilities to transparent glass.

Armajani notes a turning point in his practice: "The alchemy of my works comes from the base metals of others. In the year 2000 my work, which since 1968 had been public, functional, neighborly and open, turned personal and melancholic. I have tried for years to fight against and hide this, but failed."[18] Works such as Murder in Tehran begin to critique specific contemporary events, in this case the killing of the protester Neda Agha-Soltan during the 2009 uprisings in Tehran.

The Second Battle of Fallujah—a joint American, British, and Iraqi offensive in the Iraqi city—results in the bloodiest conflict of the Iraq War. Armajani begins working on Fallujah (2004–2005), a response to the conflict inspired by Picasso's Guernica (1937).

Exhibits in Gardens of Iran: Ancient Wisdom, New Visions at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art.

Returns to Iran at the official invitation of the Iranian minister of culture to give a lecture at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art. Is invited to design a garden in Tehran.

Continues the tomb series, sculptures dedicated to, as the artist states, the "philosophers and poets who formed and conditioned my thoughts and work."[19] Begun in 1972 with Tomb for John Berryman, the series includes tombs for Sacco and Vanzetti, Martin Heidegger, and Arthur Rimbaud.

Armajani's films are exhibited together for the first time in Art Expanded at the Walker Art Center.

Seventy-one refugees and migrants from Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan are found dead in the back of an airtight refrigerated food truck abandoned on the side of an Austrian motorway. The asylum seekers suffocated at some point during their 530-mile journey from Roszke, Hungary, to Munich.

The following year Armajani begins Seven Rooms of Hospitality, a series of 3D-printed models that address the global refugee crisis. These works are influenced by a conversation between Jacques Derrida and Anne Dufourmantelle.[20] Room for Asylum Seekers replicates the logo on the truck in which the migrants were discovered.

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, exhibits Armajani's Elements #30 (1990) as part of an installation of works from the museum's permanent collection by artists from the countries impacted by a travel ban instituted by a presidential executive order.

Armajani's Irene Hixon Whitney Bridge is repainted after twenty-five years and lit for the first time according to his original plans in advance of the artist's first major US retrospective at the Walker Art Center and The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

[1] Felix Frankfurter, "The Case of Sacco and Vanzetti," Atlantic Monthly, March 1927.

[2] Siah Armajani, conversation with Victoria Sung, December 9, 2016.

[3] Siah Armajani, conversation with Victoria Sung, June 14, 2016.

[4] Siah Armajani, in Calvin Tomkins, "Open, Available, Useful," New Yorker, March 19, 1990, 52 (quotation slightly amended by the artist).

[5] Martin Heidegger, "Building Dwelling Thinking," in Poetry, Language, Thought, trans. Albert Hofstadter (New York: Harper & Row, 1971), 196.

[6] Siah Armajani, "Tombs 1972–2014," in Siah Armajani: The Tomb Series (New York: Alexander Gray Associates, 2014), 2.

[7] Siah Armajani, in Siah Armajani, 1957–1964, exh. brochure (New York: Meulensteen Gallery, 2011); reprinted in this volume (p. 380).

[8] Siah Armajani, conversation with Victoria Sung, February 3, 2017.

[9] Quoted in Tomkins, "Open, Available, Useful," 54.

[10] Robert Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1966), 16.

[11] Siah Armajani, "Interview with Linda Shearer," in Young American Artists: 1978 Exxon National Exhibition (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1978), 17.

[12] Sol LeWitt, "Paragraphs on Conceptual Art," Artforum 5 (June 1967): 79.

[13] Quoted in Tomkins, "Open, Available, Useful," 170.

[14] Siah Armajani, conversation with Victoria Sung, June 14, 2016.

[15] John Dewey, Art as Experience (New York: Perigee, 1980), 344.

[16] Siah Armajani, quoted in Nancy Princenthal, "The Odyssey of Home," in Siah Armajani: Elements (New York: Max Protetch Gallery, 1991), n.p.

[17] Siah Armajani and Cesar Pelli, quoted in Jean-Christophe Ammann, "An Introduction," in Siah Armajani (Basel: Kunsthalle Basel, 1987), n.p.

[18] Armajani, "Tombs 1972–2014," 2.

[20] See Jacques Derrida and Anne Dufourmantelle, Of Hospitality, trans. Rachel Bowlby (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000).

Siah Armajani (Iranian-American, born Tehran, 1939). Details from Dictionary for Building, 1974–75. Mixed media. Collection MAMCO, Geneva