On July 20, 1969, half a billion viewers around the world watched as NASA's Apollo 11 mission beamed to earth the first television broadcast of astronauts on the moon. This shared experience dramatically expanded the scope of human vision, satisfying an age-old curiosity about our planet's only natural satellite. To celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of that landmark event, this exhibition, spanning five galleries, surveys the role photography has played in the scientific study and artistic interpretation of the moon from the dawn of the medium to the present.

When the astronomer François Arago announced the invention of photography to the French parliament in 1839, he predicted the new medium's potential to map the visible surface of the moon. Over the course of the nineteenth century, astronomers coupled cameras with telescopes to capture ever sharper images of our satellite's topography, culminating in the masterful French atlas displayed here in its entirety (Gallery 852). Alongside these scientific achievements, artists exploited photography's optical realism to create convincing illusions of space travel, life on the moon, and the otherworldly effects of moonlight here on earth.

Advances in rocket science and the Cold War space race of the 1960s ushered in a new phase of lunar exploration. Soviet and American spacecraft photographed the moon's rugged terrain at close range, scouting potential landing sites for their crewed missions. The final section of the exhibition (across the hall, in Gallery 851) features art created in the wake of the 1969 moon landing, as well as the visions of a new generation of artists exploring the legacy of lunar photography.

Two centuries before the invention of photography, the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) published the first drawings and descriptions of the moon as viewed through a telescope. His groundbreaking book Starry Messenger (Sidereus Nuncius, 1610) launched the field of selenography, the study of the lunar surface. As telescopes improved, hand-drawn maps charted newly identified topographical features and became important evidence in scientific debates.

With the advent of photography in the 1830s, astronomers applied the new medium to the task of mapping the moon, and immediately encountered a significant technological challenge. Exposure times were long and the earth and its satellite are in constant motion. Making a clear image required a clockwork mechanism to move the camera and telescope in sync with the moon. Much of the history of early astronomical photography is a record of the incremental advances that made it possible to overcome this obstacle.

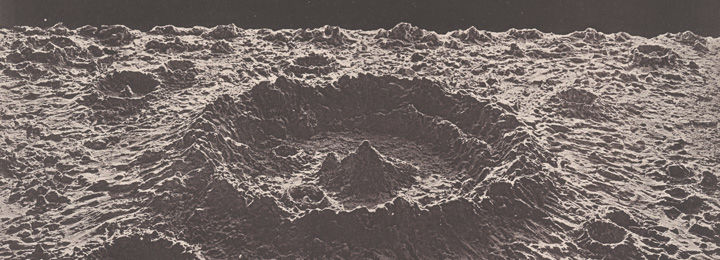

James Nasmyth. Normal Lunar Crater (detail), in The Moon: Considered as a Planet, a World, and a Satellite, by Nasmyth and James Carpenter, 1874. Heliotype. Private collection.

A capstone of nineteenth-century astronomical photography, Maurice Loewy and Pierre Puiseux's Photographic Atlas of the Moon—displayed here in full—would remain the most detailed and comprehensive set of lunar maps until the era of space travel. Beginning in 1894, the astronomers spent every clear night photographing the moon through the Paris Observatory’s powerful refractor telescope, the Grand Equatorial Coudé. The instrument was equipped with a clockwork mechanism adjustable to 3,600 speeds, a necessity for tracking the moon’s variable movements.

Over the course of fourteen years, the partners produced more than six thousand dry-plate glass negatives, choosing only the best for publication. The negatives were enlarged and transferred to etching plates to create photogravures of unprecedented clarity and size. Issued in twelve installments, the seventy-one plates came overlaid with tissue sheets that delineated the moon's topographical features.

Maurice Loewy and Pierre Puiseux. Fascicle 6, Plate 30 (detail), from Photographic Atlas of the Moon, Published by the Paris Observatory (Atlas photographique de la lune, publié par l’Observatoire de Paris), 1896–1910. Published by Imprimerie Nationale, Paris. Private collection.

Since Galileo's time, the moon has inspired both scientific inquiry and imaginative flights of fancy. Astronomical discoveries of the early 1600s prompted a profusion of fictional lunar voyages and speculations about the possibility of life on the moon. With the rise of cinema in the twentieth century, fantasies of space travel grew animated. Featured in this gallery are excerpts from three influential cinematic voyages that prefigured the modern space age: Georges Méliès's whimsical A Trip to the Moon (1902); Fritz Lang's science-fiction melodrama Woman in the Moon (1929); and Destination Moon (1950), the first major Hollywood space-travel movie.

While many artists and writers were daydreaming about life on the moon, others were equally captivated by the mystery and enchantment of moonlight. The fascination with lunar effects among Romantic artists of the early nineteenth century coincided with a fashion for transparencies—paintings or prints of atmospheric scenes designed to be illuminated from behind. Night photography posed challenges in the early years of the medium, but practitioners devised a variety of techniques—including underexposure, tinting, and retouching—to transform daylight views into shimmering moonlit nocturnes.

Chesley Bonestell. Study for A Lunar Landscape (detail), 1957. Acrylic over photomontage. Randy and Yulia G. Liebermann Lunar and Planetary Exploration Collection.

On May 25, 1961, President John F. Kennedy stood before a joint session of Congress and announced the goal of "landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth" before the end of the decade. The decision to send an American astronaut to the moon was a strategic one. Beginning in 1957 with the Soviet Union's surprise launch of the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, space exploration had become a public arena in which rival Cold War superpowers battled for political and technological supremacy.

In addition to rallying public support for space exploration, photography played an important practical role in identifying potential lunar landing sites. Both the Soviet and American space programs launched numerous crewless reconnaissance missions to photograph the moon's surface at close range and relay images back to earth. Astronauts on crewed missions captured some of the most awe-inspiring photographs of the twentieth century. Ironically, the pictures that struck the deepest chord with the public and astronauts alike were not of the moon but of our home planet—cosmic selfies shot from a quarter million miles away.

Neil Armstrong, NASA Apollo 11. Buzz Aldrin Walking on the Surface of the Moon near a Leg of the Lunar Module (detail), 1969. Chromogenic print. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mary and Dan Solomon, 2016 (2016.796.24).

Once the moon had been reached through the efforts of science, it took on new meanings in art. Humanity's relationship to the cosmos had changed, and artists were quick to respond. In the 1960s and 1970s, photographs related to space exploration permeated the mass media. Many artists, including Robert Rauschenberg, Nancy Graves, and Michelle Stuart, incorporated space-age imagery into their work, exploring the ways in which photography shapes our experience of nature and technology. A select few had the chance to treat the moon itself as a museum, creating tiny works of art that astronauts deposited on the lunar surface.

More recently, artists such as Cristina De Middel and Aleksandra Mir have staged or re-created imagery associated with the moon landing, addressing with wry humor the heroic rhetoric and cultural biases of the Apollo era. Contemporary works by Darren Almond, Sharon Harper, Kiki Smith, and others hark back to the dawn of astronomical photography, conjuring the magic of moonlit nights and the enduring sense of wonder inspired by our closest celestial companion.

Jojakim Cortis and Adrian Sonderegger. Making of AS11-40-5878 (by Edwin Aldrin, 1969) (detail), 2014. Chromogenic print. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Vital Projects Fund Inc. Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 2019 (2019.54). © Jojakim Cortis and Adrian Sonderegger

Neil Armstrong (American, 1930–2012), NASA Apollo 11. Buzz Aldrin Walking on the Surface of the Moon Near a Leg of the Lunar Module (detail), 1969. Dye transfer print, 16 1/8 x 16 3/8 in. (41 x 41.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Alfred Stieglitz Society Gifts, 2017 (2017.421)