The commemorative medal has its origins in 15th-century Italy. Several aspects of early Italian Renaissance culture led almost inexorably to the rise of the medal: the humanist emphasis on the primacy of the individual, the revival of classical antiquity, and the related desire to perpetuate personal fame and achieve earthly immortality in emulation of the great persons of the ancient world.

The medal succeeded in memorializing many men and women who might otherwise have disappeared from the historical stage. These small disks of metal, wood, or stone communicate a wealth of information about their portrait subjects, either explicitly or in the obscure language of symbol, allegory, and emblem. Through text and image, the medal celebrates an individual's unique qualities, power, accomplishments, family status, dynastic links, aspirations, beliefs, and significant life events (such as birth, marriage, and death).

The most successful portrait medals also convey the artist's skill in composing complex and balanced designs within the confines of a tiny circle, through the use of elegant lettering, sensitive portraiture, subtle modeling of forms and textures, and rich narratives. At its best, the medal embodies quintessential Renaissance values: purity of style, harmony, dignity, balance, and the gravitas regarded as an important foundation of character.

The inventor of the commemorative portrait medal was Pisanello (1395–1455), one of the most celebrated Italian painters and draftsmen of the first half of the 15th century. A peripatetic artist, he worked at the Italian courts of Ferrara, Mantua, Milan, Naples, and Rimini as well as in Verona and Rome, producing medals for numerous rulers.

In 1438 Pisanello witnessed and made sketches of the Byzantine emperor John VIII Paleologus's arrival in Ferrara to attend the ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church. The artist subsequently produced a circular commemorative relief of cast metal (approximately 10 cm in diameter) with a portrait of the emperor on one side and a narrative scene on the reverse—the first true Renaissance portrait medal.

The patron surely intended to recall and continue a virtually unbroken series of Roman imperial portraits on coins, but Pisanello's creation bore little resemblance to those works. The format probably came, in part, from other sources, including both seals and the famous Constantine and Heraclius "medals" or jewels that belonged to Jean de France, duc de Berry (1340–1416), and were thought at the time to be ancient.

The steady flow of commissions that followed demonstrates the success of Pisanello's invention, which became highly popular and fashionable among the princely courts of Italy. By the end of the 15th century, medals depicting men and women on many levels of society were circulating throughout Europe.

Pisanello produced some 26 medals over a period of 10 years. While he signed all his medals Opus Pisani Pictoris (made by the painter Pisanello), his unequaled skill as a medalist is evident in the low relief, the sophisticated representation of space, the subtle modeling and sensitivity of his portraits, and the imaginative content on the reverse sides.

Pisanello's invention fulfilled a cultural need generated by the prevailing ethos in early Renaissance Italy. Here was an object that both revived an ancient form and served as an ideal vehicle for perpetuating an individual's image and trumpeting his or her achievements, beliefs, aspirations, and social standing. If one sought lasting fame, commissioning a medal seemed an unquestionable means of attaining that goal. The medal combined the traditional advantages of the printed word and the portrait in a durable, reproducible, and easily disseminated form.

Renaissance medals were produced through casting or striking. To begin the casting process, the artist carved a model based on a preparatory drawing. In Italy, models were usually fashioned from beeswax on a disk of slate, wood, or glass. Having formed the images for each side of the medal, the artist would next add letters by direct modeling (cutting them into a ring and pressing it into the wax) or with punches that produced raised letters in the wax. The completed model was then pressed into a soft material, leaving a negative design, or mold. A mold could be made of a glue binder mixed with ashes, salt and water, or fine sand, or a compound of gesso, pumice, water, and sizing material.

The molds for the obverse and reverse were dried and fitted together with openings for the introduction of molten metal and the escape of gases. Metal (usually a copper alloy, a lead-tin alloy, gold, or silver) was then poured into the mold and cooled. After its removal from the mold, a freshly cast medal often required chasing (the removal of any spurs or irregularities from the surface) and the addition of a lacquer or chemical surface treatment to create a more attractive tone.

Striking (fig. 1) involves the use of force to create an impression on a piece of metal (called a blank, flan, or planchet) using metal dies that have been cut or stamped with negative designs. In ancient and medieval times, striking was done by placing the blank between two dies and using the blows of a hammer on the upper die to transfer the design.

Striking (fig. 1) involves the use of force to create an impression on a piece of metal (called a blank, flan, or planchet) using metal dies that have been cut or stamped with negative designs. In ancient and medieval times, striking was done by placing the blank between two dies and using the blows of a hammer on the upper die to transfer the design.

Left: Fig. 1. The striking process

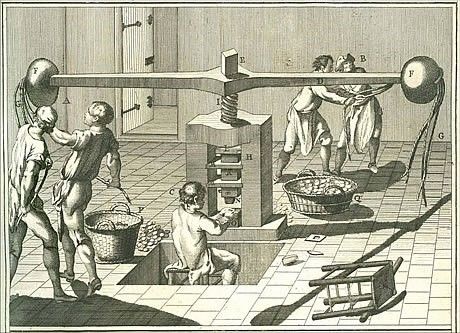

By the beginning of the 16th century, striking was more commonly done with a screw press (fig. 2), a machine adapted from printing and wine production. The upper die was attached to a long screw that could be driven down forcefully via a counterweighted arm to create impressions on both sides of a blank, which had been cast from a mold or stamped from a sheet of rolled metal.

Fig. 2. "Screw Press," from Denis Diderot and Jean Le Rond d'Alembert, Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (Paris, 1751).

The screw press was used to standardize coins as units of commerce, produce them in greater numbers, and create examples of greater diameter and higher relief. While medals derive in large part from coins, they are distinct in that they are commemorative, can be commissioned by anyone, may be produced by casting or striking, and need not conform to any standards of size, weight, or material.

Massimiliano Soldani (Italian, 1656–1740). Francesco Redi, 1677. Model for medal, wax on slate, Diam. 6.6 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.1320 a)