The first major exhibition of Chinese contemporary art ever mounted by the Metropolitan, Ink Art explores how contemporary works from a non-Western culture may be displayed in an encyclopedic art museum. Presented in the Museum's permanent galleries for Chinese art, the exhibition features artworks that may best be understood as part of the continuum of China's traditional culture. These works may also be appreciated from the perspective of global art, but by examining them through the lens of Chinese historical artistic paradigms, layers of meaning and cultural significance that might otherwise go unnoticed are revealed. Ultimately, both points of view contribute to a more enriched understanding of these artists' creative processes.

For more than two millennia, ink has been the principal medium of painting and calligraphy in China. Since the early twentieth century, however, the primacy of the "ink art" tradition has increasingly been challenged by new media and practices introduced from the West. Ink Art examines the creative output of a selection of Chinese artists from the 1980s to the present who have fundamentally altered inherited Chinese tradition while maintaining an underlying identification with the expressive language of the culture's past.

Featuring some seventy works by thirty-five artists in various media—paintings, calligraphy, photographs, woodblock prints, video, and sculpture—created during the past three decades, the exhibition is organized thematically into four parts: The Written Word, New Landscapes, Abstraction, and Beyond the Brush. Although all of the artists have challenged, subverted, or otherwise transformed their sources through new modes of expression, Ink Art seeks to demonstrate that China's ancient pattern of seeking cultural renewal through the reinterpretation of past models remains a viable creative path.

Example:

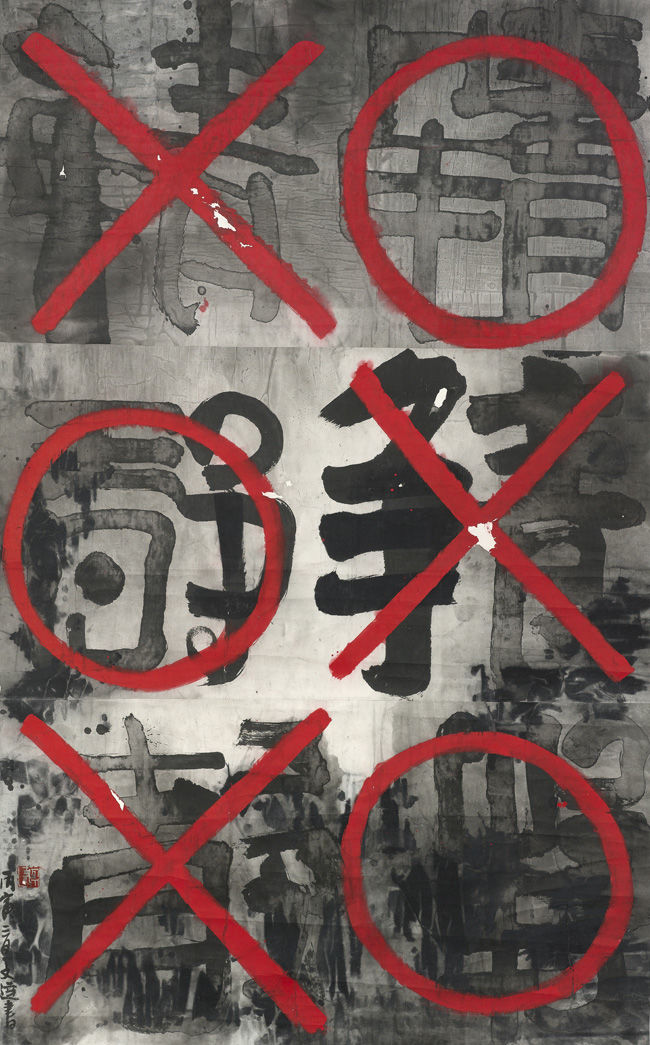

Gu Wenda. Mythos of Lost Dynasties Series—I Evaluate Characters Written by Three Men and Three Women. China, 1985. Hanging scroll; ink on paper. Image: 9 ft. 4 1/4 in. × 70 1/16 in. (285.1 × 178 cm). Lent by a private collection, Hong Kong

Writing is China's most fundamental means of communication as well as its highest form of artistic expression. Valued for both its semantic content and aesthetic significance, the written word conveys both personal and public meaning. Authors have long exploited the multiple, even contradictory meanings of many ideographs to create veiled commentaries on political and personal issues, while calligraphers have adopted specific styles to reflect their mental state or point of view. Given the inherent power of this universal medium, the written word—particularly brush-written calligraphy—has been a rich terrain for artistic exploration in China. This section of the exhibition—which comprises three subsections—examines the many ways in which writing may exist as an aesthetic language independent of semantic content.

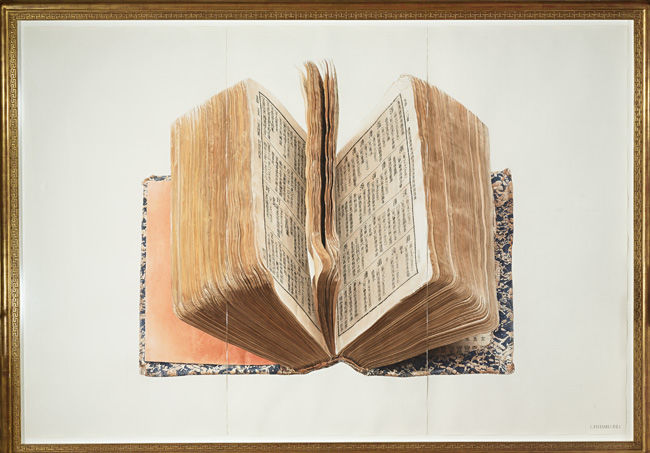

Liu Dan. Dictionary. China, 1991. Ink and watercolor on paper. Image: 81 1/8 in. × 10 ft. (206 × 304.8 cm). Lent by Collection of Akiko Yamazaki and Jerry Yang

Artists have utilized various interventions—writing with dilute ink or with a burning instrument or by employing trompe l'oeil realism on a grand scale—to divorce writing from its traditional role and give it a new pictorial or sculptural dimension. The brush-written components of Chinese calligraphy have even been deconstructed and adapted to transform English into a character-based form of communication.

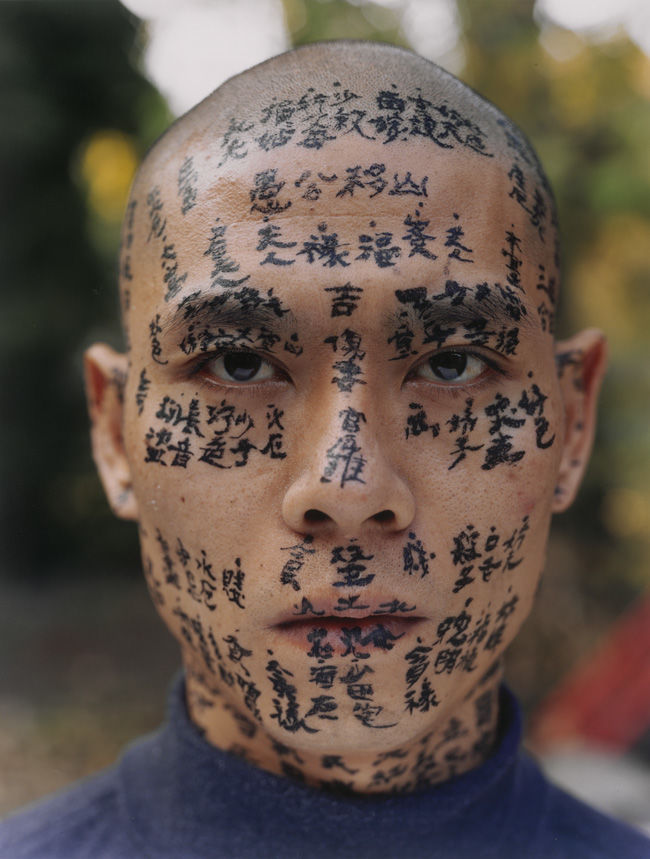

Zhang Huan. Family Tree. China, 2001. Nine chromogenic prints. Sheet (each): 21 in. × 16 1/2 in. (53.3 × 41.9 cm). Image courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery, Leonard C. Hanna, Jr., Class of 1913, Fund

Three series of photographs address the traditional calligraphic discipline of replicating texts over and over again—either as an act of merit in the case of holy scriptures, or as a means of attaining individual proficiency. In the latter case, students immerse themselves in the study of past models until the physical rhythms of a writing style became second nature—much the way an athlete or musician gradually masters increasingly demanding techniques. Such mastery is regarded as a necessary first step in achieving creative freedom.

The works displayed in this section question the consequences of repetition. It may lead to a meditative state of higher consciousness, but it may ultimately leave no lasting impression. It may also obliterate the original content of a text or the individuality of the practitioner—or both.

徐冰 天书 Xu Bing (b. 1955). Book from the Sky, ca. 1987–91. Installation of hand-printed books and ceiling and wall scrolls printed from wood letterpress type; ink on paper. Collection of the artist

Book from the Sky, first mounted in China in 1988 and 1989 and subsequently displayed many times in different countries, is one of the most iconic works of contemporary Chinese art. The presentation within Ink Art, overseen by the artist and his studio, reflects the specific characteristics of this space, but remains consistent with the artist's desire to create an environment that immerses the viewer in a sea of imaginary words: open books spread across the floor, long sheets suggestive of handscrolls suspended from the ceiling, and bulletin-board–like arrays of vertical panels along the walls.

But while the work is inspired by the form and typography of traditional Chinese woodblock publications, faithfully replicating every stylistic detail of traditional Chinese printing, not a single one of its roughly 1,200 characters—each printed with type hand-carved by the artist—is intelligible. Each of these imaginary characters conveys the appearance of legibility but remains defiantly undecipherable.

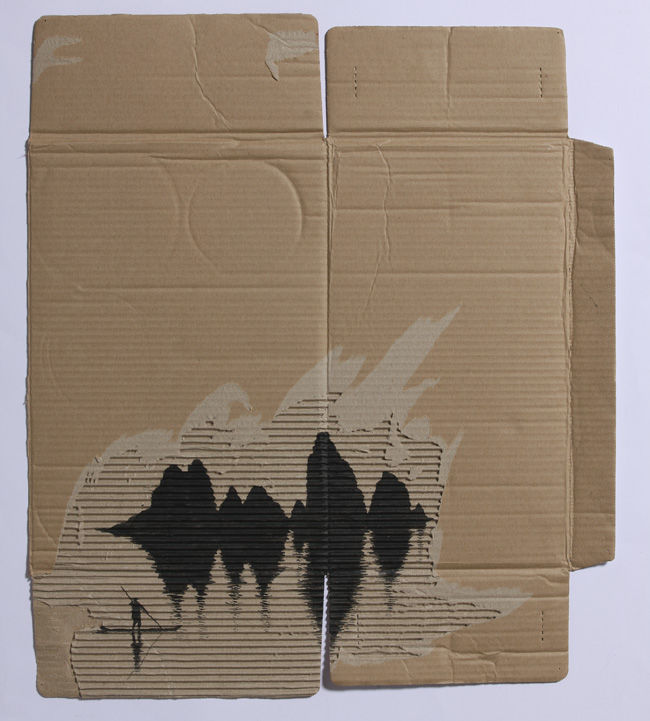

Duan Jianyu. Beautiful Dream 4. China, 2008. Ink on cardboard. 17 1/4 × 13 in. (43.8 × 33 cm). Lent by the Sigg Collection

Over the past one thousand years, landscape imagery in China has evolved beyond formal and aesthetic considerations into a complex symbolic program used to convey values and moral standards. In the eleventh century, court-sponsored mountainscapes with a central peak towering over a natural hierarchy of hills, trees, and waterways might be read as a metaphor for the emperor presiding over his well-ordered state. At times of political turmoil, images of blasted pine trees, windblown bamboo, or rustic retreats conveyed notions of survival, endurance, and withdrawal from the world. Today, as China is transformed by modernization, artists continue to mine the symbolic potential of landscape imagery to comment on the changing face of China and to explore the "mind landscape" of the individual. The paintings, photographs, videos, and animation in this section of the exhibition highlight the diverse ways in which contemporary artists have drawn inspiration from earlier compositions and themes. Some offer stark commentaries on China's rapidly expanding urban landscapes, while others explore man's dynamic relationships with changing environments, both built and natural.

墨水城市/Ink City, 2005. Chen Shaoxiong. Video (black and white, sound)/3 min. loop

Since the late 1980s, Chinese artists have embraced video as a way to engage critically with issues of globalization and cultural identity. Many of these works include imagery appropriated from China's past, including ancient landscape painting and early twentieth-century Chinese cinema, as well as from contemporary life. Animated videos, in particular, have been laboriously crafted employing traditional mediums such as ink sketches or woodblock printing to present trenchant commentaries on urban experience, material culture, or narratives of China's recent past.

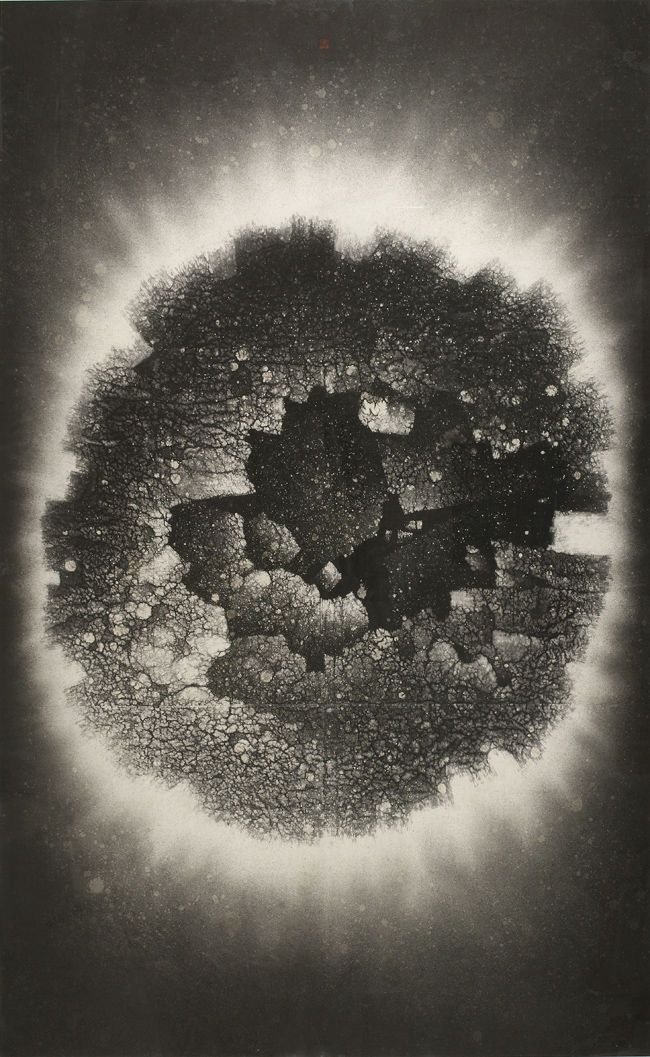

Zhang Yu. Divine Light Series No. 59, The Floating Incomplete Circle. China, 1998. Hanging scroll; ink on paper. Image: 9 ft. 7 3/8 in. × 70 7/8 in. (293 × 180 cm). Lent by a private collection, Hong Kong

Abstraction lies at the very heart of Chinese painting and calligraphy. Because the brush mark, in addition to performing a descriptive or semantic role, has always been recognized as a record of the artist's hand, both painting and calligraphy have been valued for their abstract expressive potential. Benefitting from this rich tradition of exploiting the abstract and symbolic qualities of painting and writing, contemporary Chinese artists have selectively engaged with Western notions of nonfigurative art to augment and expand their expressive goals. Some artists have used their command of traditional techniques to create large-scale abstractions emphasizing the dynamic gestural qualities of calligraphy while divorcing the work from any suggestion of semantic meaning. Others have used traditional media to create new nonfigurative imagery, to explore the materiality of their chosen medium, or to emphasize artistic process.

Huang Yongping. Long Scroll. China, 2001. Handscroll; watercolor, pencil, colored pencil, and ink on paper. Overall: 13 1/4 in. × 50 ft. 3 in. (33.7 × 1531.6 cm). Lent by The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Some works in the exhibition defy easy categorization, but all display what might be termed an "ink aesthetic" through their selective revival of past models. One group is made up of conceptual or performance-based pieces that nevertheless make use of traditional media or formats to create permanent records of ephemeral installations or events. A second group includes three-dimensional works that do not use ink itself as a medium, but that embody an ink aesthetic in so far as their forms are inspired by traditional artworks that derive from Chinese literati pastimes or patronage.

The catalogue is made possible by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Richard and Geneva Hofheimer Memorial Fund, and Marie-Hélène Weill.