Visiting Guide

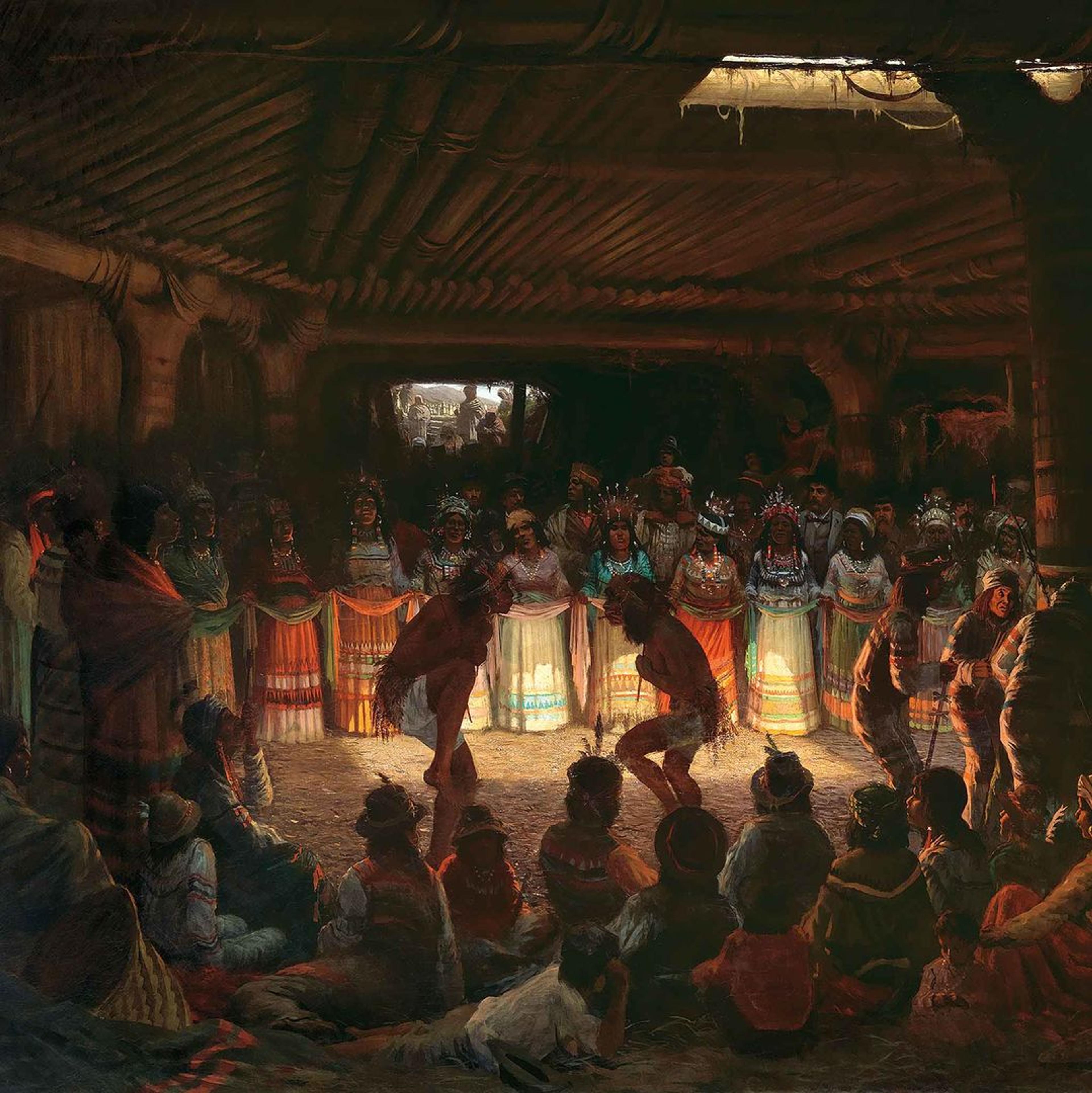

In 1876 the French-born and -trained American artist Jules Tavernier received the most important commission of his career from San Francisco’s leading banker, Tiburcio Parrott. The resulting painting—Dance in a Subterranean Roundhouse at Clear Lake, California—commemorates an extraordinary experience Parrott shared with Parisian business associate Baron Edmond de Rothschild. Earlier that year, both men were privileged to witness a ceremonial mfom Xe, or “people dance,” of the Elem Pomo, an Indigenous community on the southeastern shore of Clear Lake in Northern California.

While Tavernier’s grand artwork celebrates the rich vitality of Elem Pomo culture, it also exposes the threat posed by White settlers, including Parrott, who was then operating a toxic mercury mine on the community’s homelands. Designated a Superfund site by the Environmental Protection Agency in 1990, the mine continues to negatively impact the lives of the sovereign people of the present-day Elem Indian Colony. The rediscovery of Tavernier’s painting in recent times has inspired this analysis of the artist’s career and wide-ranging travels, incorporating a multiplicity of Indigenous voices and perspectives to offer new interpretations.

When Tavernier arrived in California, in 1874, the Pomo peoples had for decades suffered the consequences of White settlement, including genocidal violence, disease, land theft, forced relocation, environmental degradation, and cultural transformation. Yet in the face of colonialism, Pomo communities developed strategies of resistance and endurance that persist today. Innovation and adaptation are evident in their basketry—the art form for which the Pomo peoples are best known. The historical and contemporary examples here, including baskets by Clint McKay (Dry Creek Pomo/Wappo/Wintun), celebrate the resiliency of Indigenous Pomo peoples and highlight their continued cultural presence.

This exhibition is presented in collaboration with Elem Pomo cultural leader and regalia maker Robert Joseph Geary and Dry Creek Pomo/Bodega Miwok scholar Sherrie Smith-Ferri, Ph.D.

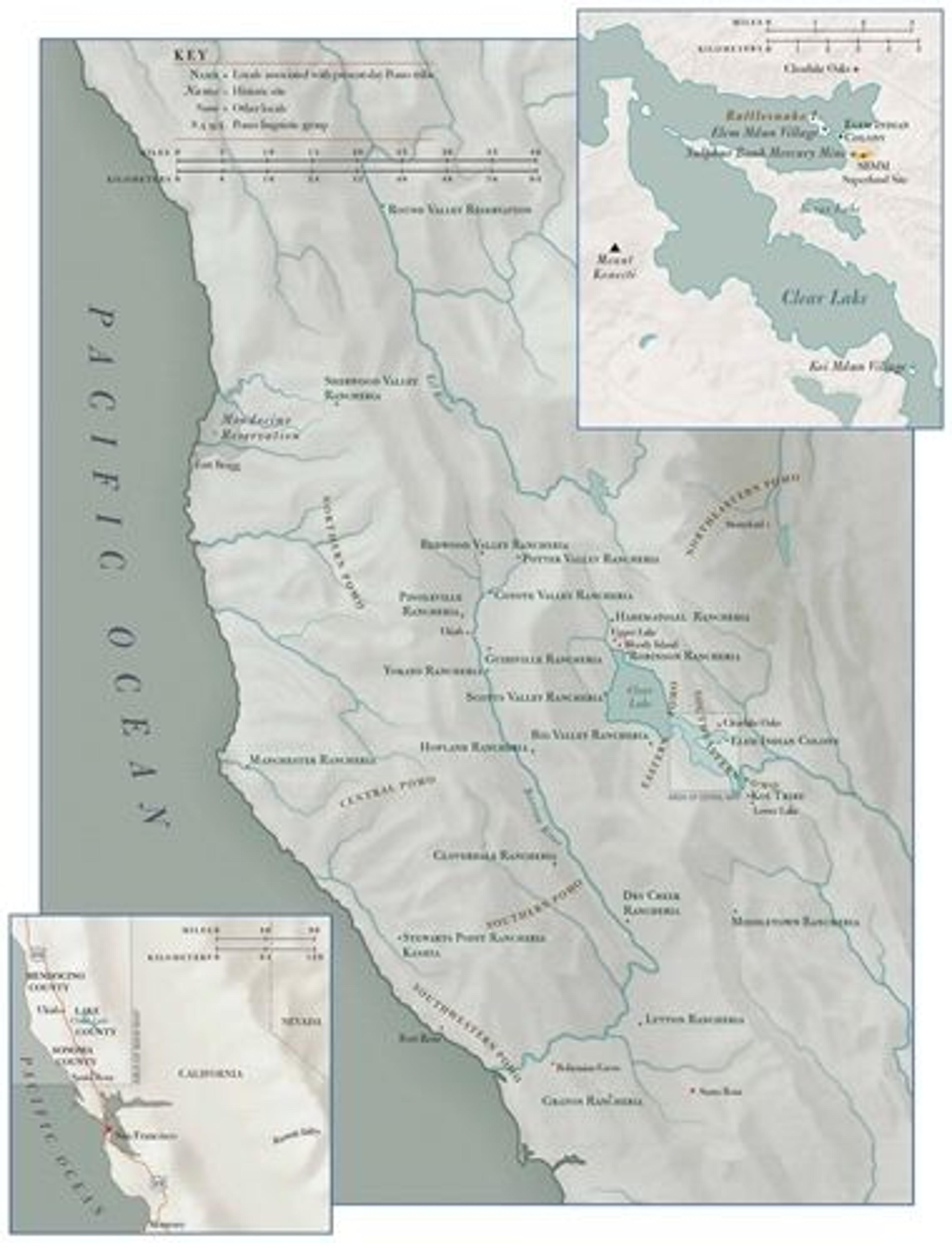

Image: Map of Northern California showing Pomo linguistic groups and present-day Pomo tribes. View full-size PDF.

A French Bohemian in the American West

Born and trained in France, Jules Tavernier (1844–1889) took life drawing classes and exhibited his paintings at the Paris Salon in the 1860s. He left London and arrived in New York in August 1871, initially showcasing his skills as an illustrator with scenes of daily life and the American wilderness. Following the opening of the Transcontinental Railroad, in 1869, the American public clamored for images of the West. Tavernier’s talent was recognized by Harper’s Weekly, who hired him, along with fellow French artist Paul Frenzeny, to travel across the country, providing the magazine’s readers with tantalizing pictures. The men filled their sketchbooks with field studies of conflicts they witnessed—a result of the rapid expansion of White settlement and the US government’s forced relocation of Indigenous communities from their ancestral lands to reservations.

Tavernier also sought out direct encounters with Native Americans, witnessing the Sun Dance ceremony and meeting Chief Red Cloud and Sitting Bull, a lieutenant headman of the Oglala Lakota Nation. The artist moved to San Francisco in July 1874 and soon became one of the city’s leading artists, serving as a prominent member of the Bohemian Club and a founder of the Monterey Peninsula Art Colony. Over the course of his short career, Tavernier would eventually produce more than thirty paintings of Indigenous peoples.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Pomo Basketmaking

The natural fertility of Pomo peoples’ homelands—largely a product of their astute environmental management—provided a settled and satisfying life. They fished rivers teeming with salmon, hunted large flocks of game birds, and harvested a wealth of native plant foods. Baskets were the main tools of life: they were used to catch, gather, store, winnow, sift, cook, and serve these foodstuffs. In addition, baskets were central to individual and community events, serving as everything from a baby’s cradle to a part of ritualized marriage exchanges or celebrations of seasonal abundance.

Pomo peoples mastered and combined numerous weaving techniques to create this wealth of baskets. There are two main ways to make a basket: twining and coiling. A twined example is constructed by interlacing supple strands between vertical foundation rods. In contrast, a coiled piece is created by wrapping fibers around a horizontal foundation. Typically, basketmaking traditions involve either twining or coiling. Pomo peoples, however, made both types of baskets, employing some eight different twining strategies and two methods of coiling—an unparalleled diversity of weaving techniques.

My grandmother, Lucy Lozinto Smith, put it best. She, her parents, their siblings, and our ancestors stretching back for millennia all wove baskets. “We were,” she assured me, “the best basketmakers in the world.”

— Sherrie Smith-Ferri (Dry Creek Pomo/Bodega Miwok; author of all texts on basketry in this exhibition)

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

The mfom Xe Ceremony

Tavernier’s painting depicts the “mfom Xe,” or “people dance,” a newer ceremony that was introduced to our community in the post-contact period by a prophet from a neighboring village northeast of Elem. The world-renewal process that was prophesied, and which is the subject of the dance, needed to be practiced immediately because the “oomthimfo” (Native people) were dying in record numbers from destruction and diseases brought by White settlers. This prophecy also came with instructions for the new ceremonial “Xe-xwan” (roundhouse), which, along with the “mfom Xe” dance, would serve to protect both the people and the land. This dance was the only one that all members of the village could partake in; children and adults danced together to create a power that would ensure our existence.

Tavernier’s likeness of the ceremonial “Xe-xwan” is impressive in terms of his ability to capture the grandeur and beauty of the interior. The stories from our elders about how these structures were made, passed down from generation to generation, ring true throughout the work. The Elem “Xe-xwan” still exists today, as do the “mfom Xe” dance and the “Elemfo” (Elem people). Nearly 150 years later, we continue to reside at the same location and have sustained our ceremonial and cultural practices.

— Robert Joseph Geary, Elem Oomthiwi (Elem Native Man)

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Tavernier in Hawai‘i, 1884–89

Tavernier’s bohemian lifestyle and unpaid bills forced him to flee San Francisco, traveling to Hawai‘i in search of new subjects for his art. Arriving in December of 1884, he declared it an “artist’s paradise.” By that time, volcanoes were already among the most iconic images associated with Hawai‘i. Tavernier painted a series of the islands’ active volcanoes, emphasizing the destructive and magnificent forces of nature. The success of these works launched what came to be known as the Volcano School, and fueled tourism to the islands. Pele, a powerful female deity in Hawai‘i who embodies the many manifestations of volcanism, is revered as an environmental force capable of changing land formations. Well-circulated stories of Pele made Tavernier’s paintings all the more marketable to visitors.

In November 1886, Tavernier completed a ninety-foot-long panorama of Kīlauea, which was shown to great acclaim and went on tour to San Francisco and beyond. When the artist died of a heart attack in his Honolulu studio at the age of forty-five, memorial tributes celebrated his creative accomplishments, but he was soon forgotten. The rediscovery of Tavernier’s Dance in a Subterranean Roundhouse has led to this new investigation of his career.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.