Fig. 1. Left: Ğičak (Ghichak), 1968. Kabul, Afghanistan. Wood, sheep bone, camel bone, mother-of-pearl, metal strips; L. 28 7/16 x W. 9 5/16 x D. 6 1/8 in. (72.2 x 23.7 x 15.5 cm); Sounding L. 14 in. (35.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mark and Greta Slobin, 2015 (2015.620.2). Right: Dutar, mid-20th century. Uzbekistan. Wood, wound silk strings(?); L. 45 11/16 x W. 8 x D. 6 1/8 in. (116 x 20.3 x 15.5 cm); Body: L. 18 7/8 in. (48 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mark and Greta Slobin, 2015 (2015.620.8)

From Ken Moore, Curator Emeritus in the Department of Musical Instruments:

Beginning in 1967, ethnomusicologist Mark Slobin worked in Afghanistan to document musical practice and traditional instruments. A professor of music and American studies at Wesleyan University, Slobin collected instruments that are now extraordinarily rare documents of mid-20th-century Afghani culture. He wrote about his research in his book Music in the Culture of Northern Afghanistan, and in 2015, he donated his collection of Afghani musical instruments to The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

«From 1967 to 1972, I traveled to Afghanistan to do dissertation fieldwork on local folk music of the north, the Central Asian part of a hugely diverse, peaceful, and developing constitutional monarchy. The people of the region were incredibly hospitable and I collected numerous musical instruments during my travels, all of which I recently donated to The Met. The entire story of my work, with multimedia documentation, is available on the Wesleyan University website, and Afghanistan Untouched, a two-disc set of musical selections I recorded in 1968, is also available.»

The people I encountered were guarded about openly playing music, since it is considered among those activities that lead to loose morals and bad behavior, like gambling, partridge fighting, and dancing boys. Local tea houses offered entertainment on semiweekly market days, and I was able to coax some performers into private sessions as my wife and I traveled around the countryside in a battered Volkswagen Beetle.

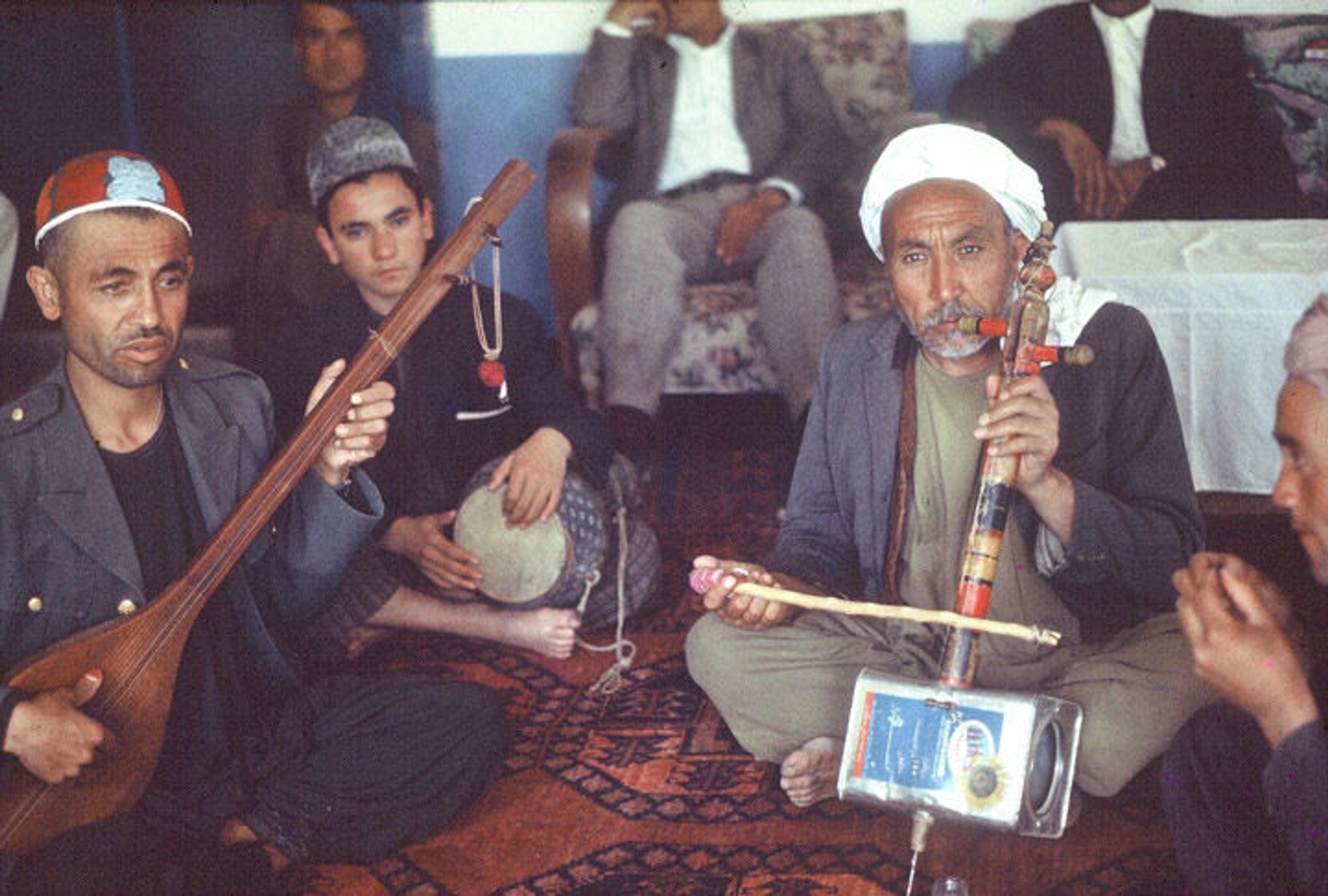

Fig. 2. Two musicians perform on tal (left) and dambura (right). Photo courtesy of the author

The dambura, a lute shared by Tajiks and Uzbeks, was often featured alongside finger cymbals, known as tal (fig. 2), or the ghichak, a fiddle with a tin-can body (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Bangecha Tashqurghani (left) performs on the dambura alongside Baba Nur (right) on the ghichak. Photo courtesy of the author

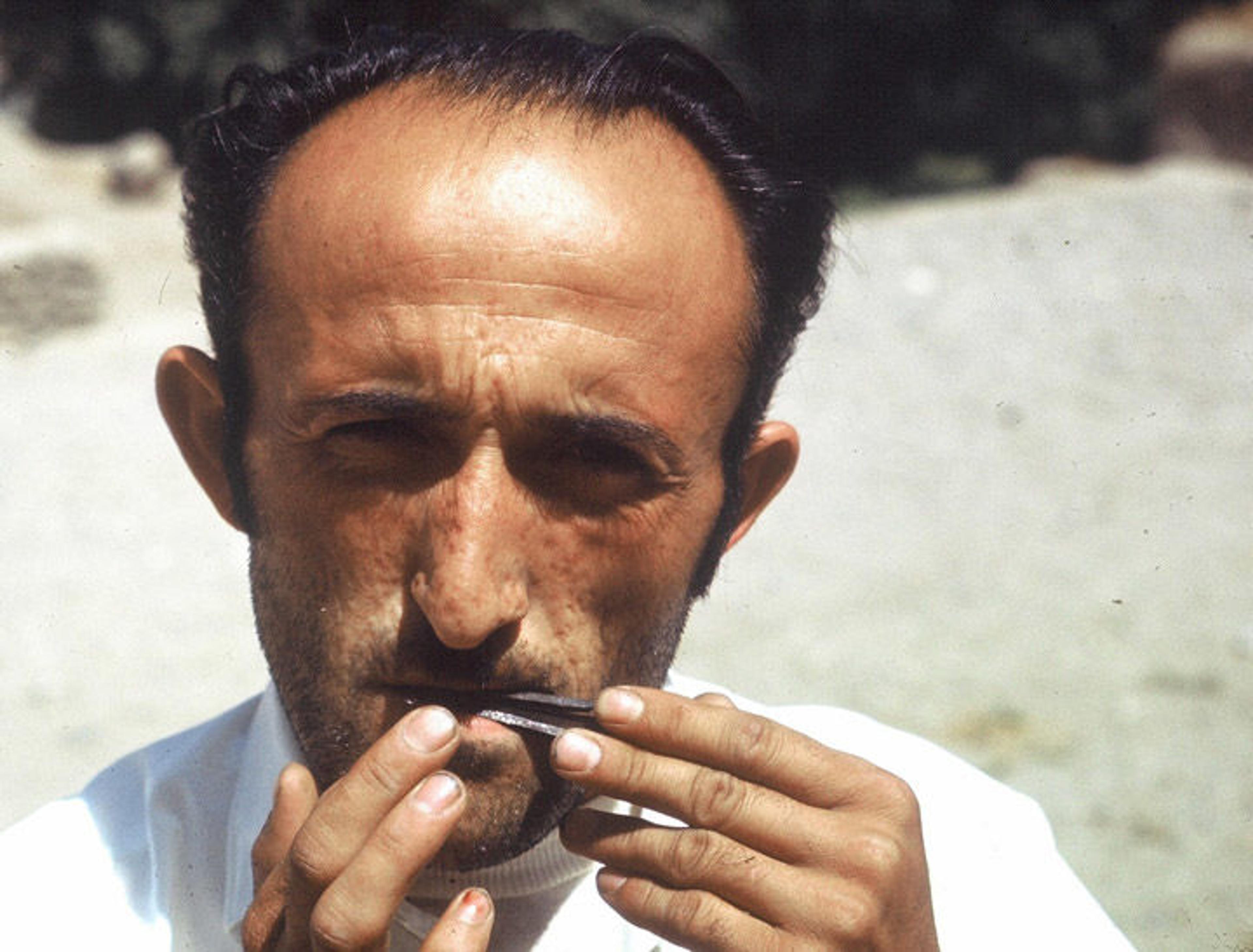

The jaw harp, chang (fig. 4), was mostly played by women and children. The musical role of women was restricted in the country, and they are most often hired just for celebrations—primarily weddings, in usually segregated sessions—or for family gatherings in the home.

Fig. 4. A musician performs on the chang. Photo courtesy of the author

There was a rare, hidden tradition of pre-Islamic shamanism I accidentally uncovered with my anthropologist friends Pierre and Micheline Centlivres. The healer went into a trance, summoning and voicing familiar spirits with the qobuz, a fiddle related to Kazakh and Kyrygyz shamanism (fig. 5).

Fig. 5. A local healer holds a qobuz while in a trance. Photo courtesy of the author

Among the other instruments now at The Met are polished river stones that are sometimes used as castanets, end-blown shepherds' flutes, recorder-like flutes, two large-fretted lutes known as dutar—one from Turkmenistan with pearl-button inlay and one from Uzbekistan that was factory-made in the former Soviet Republic—a tanbur lute with sympathetic strings and elaborate sheep-bone inlay, and both Uzbek and Tajik damburas, as well as toy drums sold to children at the time of the spring Nowruz holiday.

Outside of the shaman's qobuz, the rarest instrument I purchased was a Nuristani waj (also known as a wazh or vadzh), from an isolated mountain area of the northeast (fig. 6). An arched harp rare to the Middle Eastern/Central Asian region, the waj is descended from instruments featured on 2,000-year-old friezes in northwestern India.

Fig. 6. Waj, mid-20th century. Nūristān, Afghanistan. Wood, hide, animal hair, nylon, cloth; Total: H. 13 7/16 in.; Body: D. 2 3/8 x Greatest W. 4 x L. 19 13/16 in. (34.1 x 10.2 x 6.1 x 50.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mark and Greta Slobin, 2015 (2015.620.1)

At the time, the newly created Radio Afghanistan Orchestra combined many of these instruments, along with the rabab—the "national Afghan instrument" largely played by the Pushtun majority—the Indian sitar and harmonium, and the Western trumpet, mandolin, and piano, all grouped around a single microphone to produce a sound cloud that accompanied a celebrated singer.

I cherish the time I spent with many musicians, some of whom have perished in the ensuing, unending violence that has engulfed Afghanistan since 1978, and I am delighted that the instruments have found a safe harbor in The Met's glorious collection of musical instruments.

Related Link

Collection: View all 29 of the Afghani instruments donated to The Met by Mark Slobin in 2015.

Of Note: Jennifer Schnitker, "Conserving an Early Twentieth-Century Afghani Rubāb" (May 20, 2014)