Conserving an Early Twentieth-Century Afghani Rubāb

Photos of the Museum's early twentieth-century Afghani rubāb, before conservation treatment (above) and after (below)

«One of the recent musical instruments conserved at the Met is a twentieth-century Afghani rubāb, a short-necked lute known as the national instrument of Afghanistan. A plucked instrument, the rubāb is used in art, popular, and regional music, both as a solo instrument and as part of small musical ensembles. Prior to being displayed in The André Mertens Galleries for Musical Instruments, this object needed treatment due to losses of inlay from the fingerboard and pegbox. Additionally, this presented a good opportunity to evaluate the condition of the rawhide resonator, as this material can become more brittle over time.»

Conservation of musical instruments in the Museum's collection is a crucial component of their care and display. Evaluating each object's condition, treating those in need of intervention, and monitoring them over time contribute to the longevity of these instruments, thus allowing for greater public access. Musical-instrument conservators work with objects from a variety of cultures and time periods that can include materials ranging from wood, bone, and horn to ceramics, metal, and plastics. This variety, coupled with the fact that instruments were built to perform the specific function of producing a sound, gives rise to a number of interesting challenges for the conservator. Our treatments must take into account the many types of information that can be gleaned from these objects, which include techniques of construction, how the object may have been restored, historical evidence that provides better context, and, in certain cases, the quality of sound produced. To that end, interventions are designed to be as minimally intrusive as possible, and utilize reversible materials.

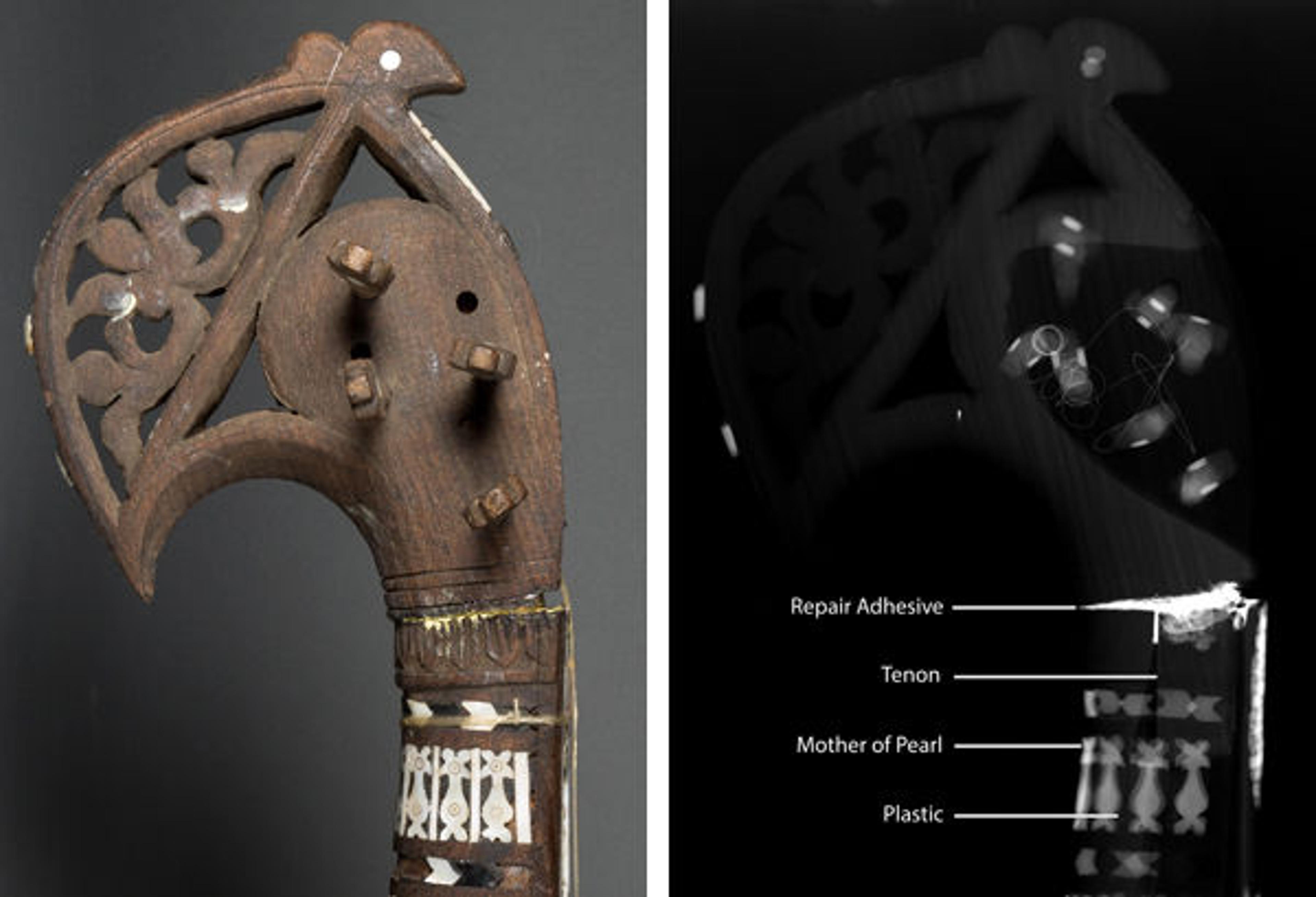

The first step of any conservation treatment involves researching the object being treated and investigating—often with the aid of analytical equipment—the materials and technologies used to create the object. With the rubāb, x-radiography was of particular help. X-rays differentiate based on density or mass, so that heavier chemical elements appear bright in the resulting image while lighter elements appear dark. Looking at the rubāb, we found that the pegbox was joined to the hollow neck with a tenon, which had been repaired with a non-traditional material (the bright white seen at the joint).

Of further interest in the x-radiograph was the difference between pieces of inlay. Those pieces that were obviously mother-of-pearl appeared bright white in the image while smaller linear elements were quite dark. This led us to suspect that these linear pieces might be plastic rather than bone, for example, which would also look bright in the x-radiograph. Through collaboration with the Met's Department of Scientific Research, we determined the plastic to be polystyrene. While it may seem cursory, finding original plastic material on an object provides a date before which it could not have been made, as mass-produced synthetic plastics were developed in the first half of the twentieth century. This information would also influence the material chosen for missing polystyrene elements.

Detail of the object's neck (left) and x-radiograph of the same area (right)

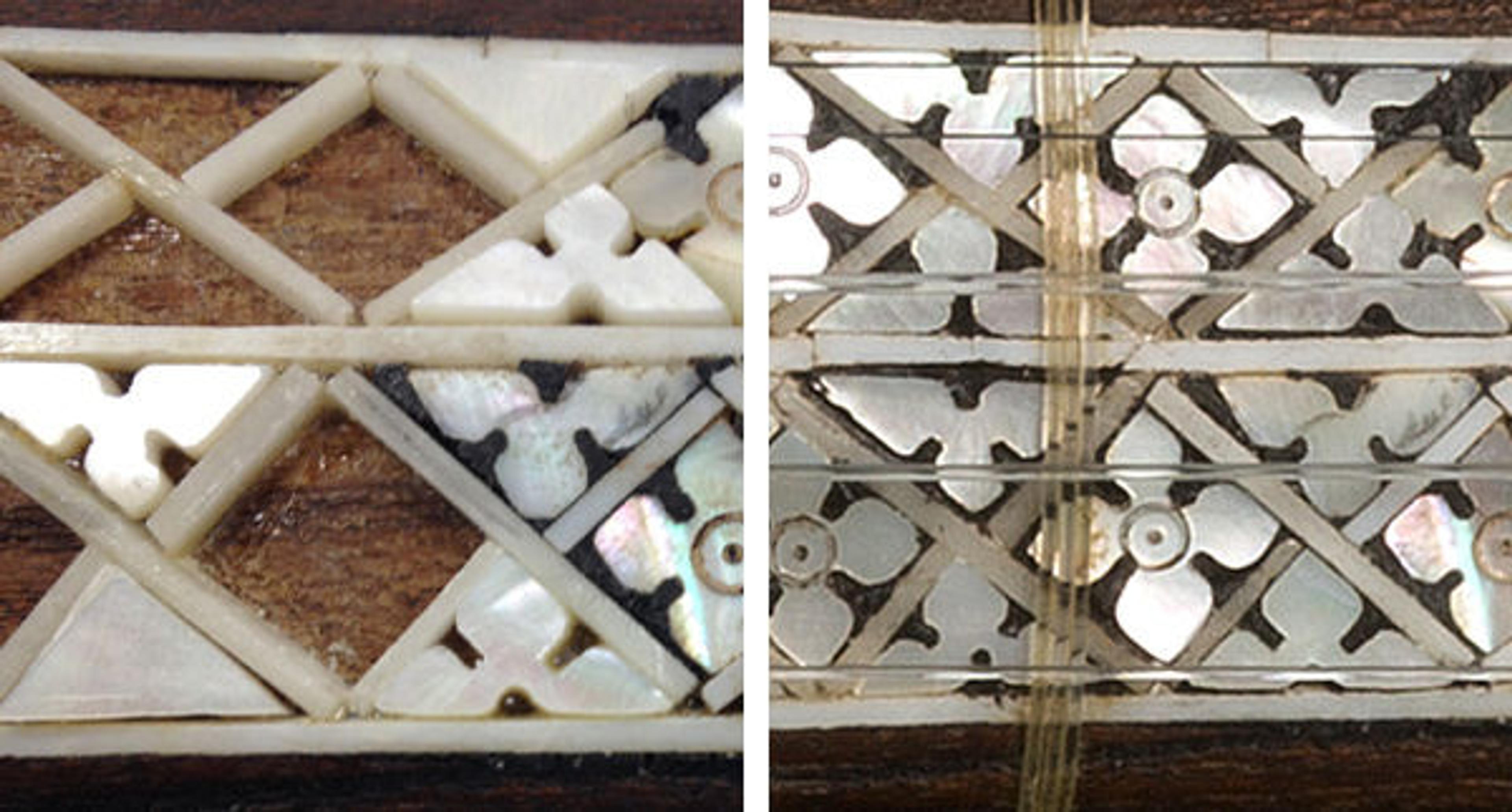

Once the materials present on this object were better understood, the lost inlay components could be recreated from compatible materials. Mother-of-pearl was chosen to replace missing mother-of-pearl elements, and shaped using hand tools that included saws, files, and sandpaper. Additionally, a special tool was created from steel rod for the purposes of scribing the circular decoration seen in the square-shaped pieces of replacement inlay. A conservation-friendly epoxy was used to imitate the polystyrene and was cast from the object in standalone molds. Bulking agents and pigments were added to the epoxy to create both the off-white and black elements needed to complete the inlay. Small clues on an object often assist in designing its treatment. With the rubāb, it was the imprint of the missing inlay left in the hide glue that conveyed exactly the shapes and sizes needed for the replacements, resulting in a new inlay that is highly representative of the lost original.

Detail of work in progress on the object's fingerboard (left) and the same area after treatment (right)

It was also necessary to fill around the inlay with a black-brown material similar to that found in the intact areas. The original material used was pigmented animal glue, also identified with the assistance of the Department of Scientific Research. In this instance a pigmented wax was chosen for the fill material due to differences in solubility between wax and animal glue. Proteinaceous animal glues are soluble in water, whereas wax is not. In the future the wax can be readily reversed, either with tools to pick the soft material out, or with a solvent that will not impact the original animal glue. It was rather amazing to see the visual impact of the black wax; since the mother-of-pearl is slightly translucent, the addition of the wax made it look darker and helped to blend with the original.

Before the addition of wax to the instrument (left) and after addition (right)

The final steps in treating this object included the creation of a nut to replace the missing one, restringing the object, and making two additional frets. For this aspect of the project, we collaborated with a rubāb player, Quraishi. Quraishi's experience and perspectives on the instrument were a valuable resource, as he was able to explain the particulars of this instrument which were not necessarily readily apparent. He offered guidance regarding the shape of the nut, appropriate stringing, and placement of the new frets.

Since this rubāb will be exhibited here at the Museum rather than performed on a concert stage, this video of Quraishi playing his own instrument at the Met in May 2013 will give an idea of the instrument's distinct character and sound.

"Valley," written and performed by Quraishi and accompanied by Samir Chatterjee on tabla. Recorded May 13, 2013, in the gallery for the art of Mughal South Asia and later South Asia.

Jennifer Schnitker

Jennifer Schnitker is an Assistant Conservator in the Department of Objects Conservation.