Fig. 1. House form, A.D. 550–900. Copán, Honduras. Maya. Stone (rhyolite); H. 15 3/4 in. (40 cm) x W. 14 9/16 in. (37 cm). © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, PM# 92-49-20/C20 & 92-49-20/C20 (digital file #99260010)

«In the early fifth century, Maya texts record that a foreigner "from the north" (presumably from modern-day Guatemala) known as K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' arrived in the fertile Copán Valley in Honduras and began building a dynastic royal court that persisted for about 500 years. The kings and queens of the city of Copán, known in ancient times as Ux Witik, sponsored artists who were renowned for their unparalleled three-dimensional sculpture in stone and stucco. Artistic ambition sponsored by the Copán rulers is still evident in all parts of the UNESCO World Heritage site today, including the eighth-century Copán hieroglyphic stairway containing the longest known Maya text, comprising more than 2,000 hieroglyphs.»

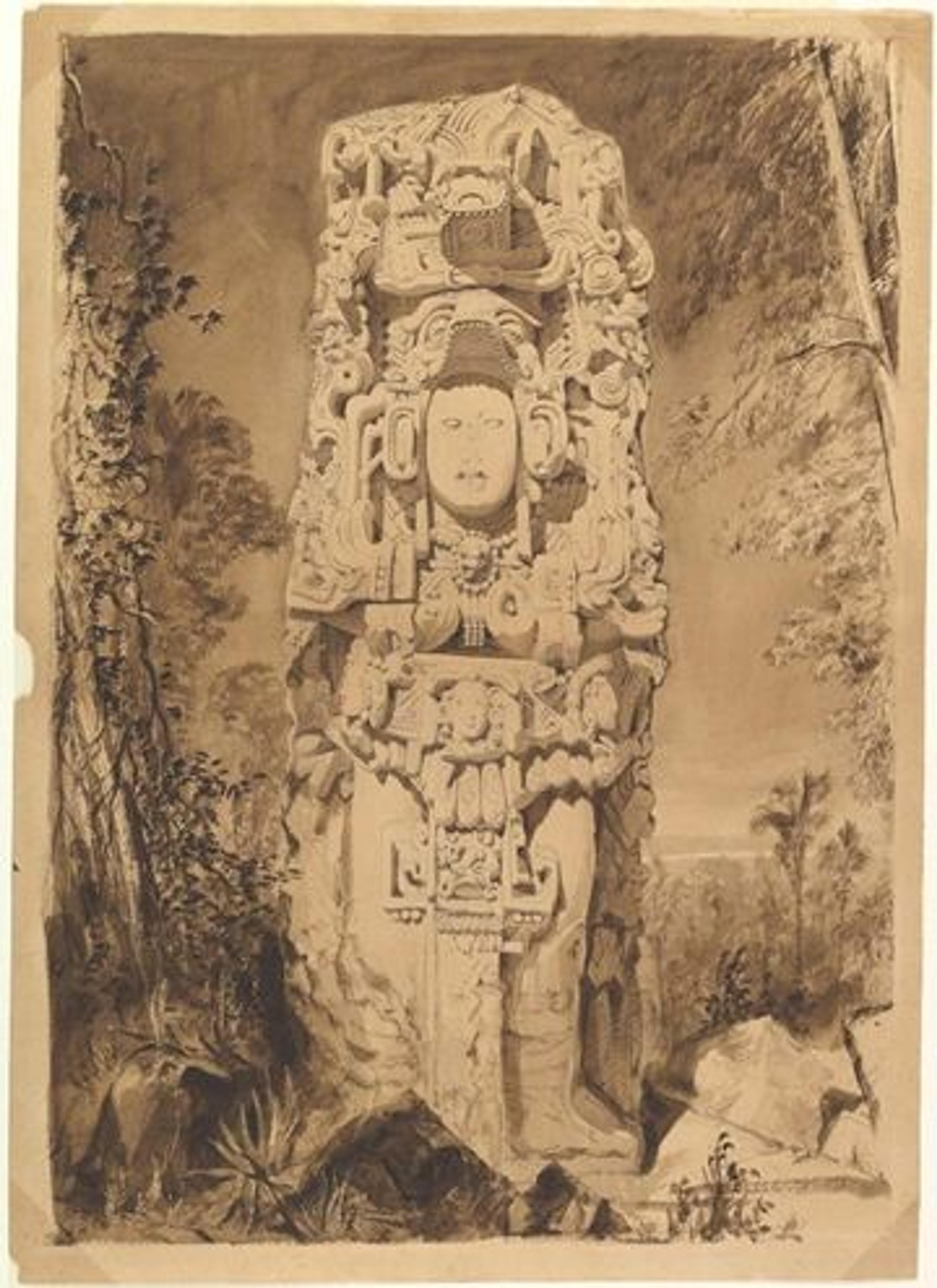

One of Copán's greatest rulers, Waxaklajuun Ubaah K'awiil, who became king in A.D. 695, was also the victim of the most infamous rebellion in Maya history. In A.D. 724, he oversaw the accession of his vassal, K'ahk Tiliw Chan Yopaat, at the neighboring city of Quirigua. Only 14 years later, however, K'ahk Tiliw Chan Yopaat captured and beheaded his former overlord, effectively ending a golden age of Maya art at Copán. A later revitalization during the 750s under the 15th ruler, K'ahk Yipyaj Chan K'awiil, produced the hieroglyphic stairway and fine sculpted stelae such as Stela N (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Frederick Catherwood (British, 1799–1854). Stela at Copán, 1843. Sepia wash over graphite; 22 7/16 x 16 1/16 in. (57.1 x 40.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund, 1953 (53.82)

Copán appears in the center of Design for Eternity: Architectural Models from the Ancient Americas, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through September 18, in the exhibition's largest model, recovered from the site in the 1890s (fig. 1). Carved in two parts, the living area and the tall peaked roof, this solid house form is part of a set of models likely used in house-dedication rituals near Mound 83, an ancestor shrine in the site's center. The artist depicted a seated deity in a niche on one side of the base and hieroglyphic captions on two other sides. Because of those captions, this model is the only one in the entire exhibition that contains information about what the people who created the object specifically thought of it.

Fig. 3. Installation view of Design for Eternity: Architectural Models from the Ancient Americas

The artists inscribed this work as "sleeping places for the gods" (waybil k'uh), showing explicitly that architectural models were seen as dwellings for the divine. A skeletal head with smoke scrolls sprouting from the top was sculpted in relief on the roof form. This head possibly represents the visage or name of the royal family's patron god, reinforcing the notion that such models were considered temporary abodes for gods and goddesses in the human world.

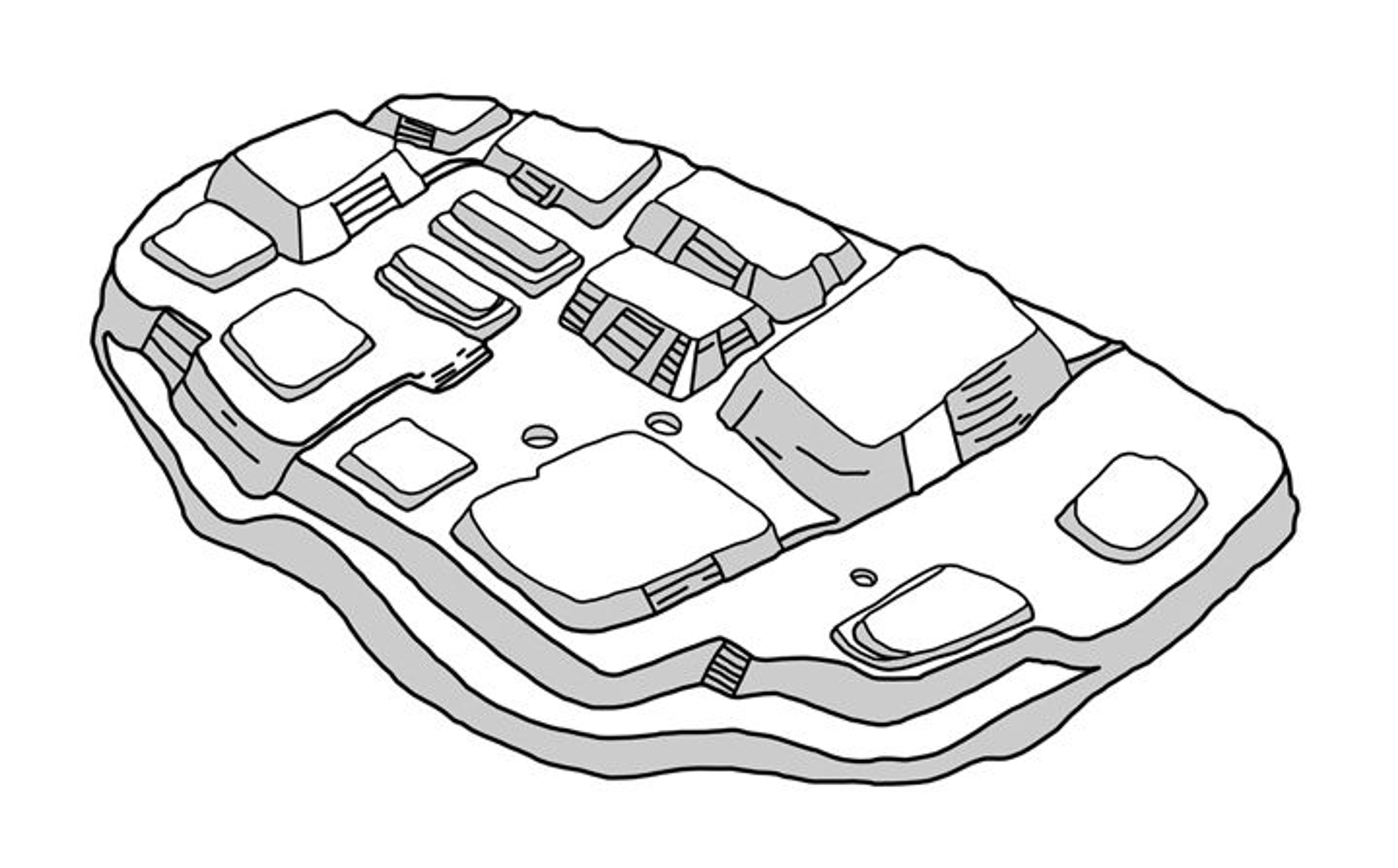

Fig. 4. Drawing of the architectural model recovered in the Mundo Perdido compound at Tikal, Guatemala. Drawing by the author, after fig. 47 in Juan Pedro Laporte and Vilma Fialko's "Un reencuentro con Mundo Perdido, Tikal, Guatemala," published in Ancient Mesoamerica 6 (1995)

The Copán model group is unusual for the Maya. As discussed in a chapter in the exhibition catalogue, the Maya were not prolific creators of small-scale architectural objects like their peers in other parts of Mesoamerica and the Andes. One other exception, excavated at Tikal, Guatemala, now resides in the Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnografía in Guatemala (fig. 4). While it may represent an acropolis of pyramidal structures, with a specificity that suggests a particular place, the model does not match any known complex at Tikal.

For the ancient Maya, then, it seems that making architectural sculptures at a reduced scale was not about capturing scenes of daily life such as feasting, ball games, or funerary rituals. Rather, artists at Copán and Tikal created mythological landscapes and dwellings for deities through deep relief carving in an enduring lithic medium.

References

Andrews, E. Wyllys, and William L. Fash, eds. Copán: The History of an Ancient Maya Kingdom. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press, 2005.

Coe, Michael, and Stephen Houston. The Maya. 9th ed. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2015.

Fash, Barbara. The Copán Sculpture Museum: Ancient Maya Artistry in Stucco and Stone. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum Press & David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Harvard University, 2011.

Fash, William L. Scribes, Warriors, and Kings: The City of Copán and the Ancient Maya. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1991.

Martin, Simon, and Nikolai Grube. Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya. 2nd ed. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2008.

Related Links

Design for Eternity: Architectural Models from the Ancient Americas, on view October 26, 2015–September 18, 2016