«It is unsurprising that Europeans arriving in the New World, including the first English pilgrims in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, quickly adopted corn as a staple grain. What remains a mystery, however, is how the early arrivals to the Western Hemisphere thousands of years ago first began creating corn, or maize. Unlike Old World grains, corn (Zea mays) was not technically "domesticated," because there is no wild form of the plant. Rather, it was entirely created from ancestral wild grasses by human populations in the fertile highlands and valleys of modern-day Mexico.»

Left: Fig. 1. Corn-stalk vessel, 6th–7th century. Peru. Nasca or Wari. Ceramic; H. 10 1/2 in. (26.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Judith S. Randal Foundation Gift, 1989 (1989.62.1)

These early residents of Mexico may, in fact, have bred larger cornseed kernels by accident as they gathered socially to eat and drink other wild products; the growth of the ancestral corn grains simply could have been a byproduct of people selecting certain grasses for other uses. Some believe that the larger grass stalks carried a high sugar content, making it desirable as a fermenting agent for early corn-based alcoholic drinks. Ethnographic evidence suggests that early peoples would have chewed the stalks and mixed the spit-laden mixture with water, leaving it to turn into what is historically known as chicha, a corn beer. If so, Mesoamerica would be a unique case in the ancient world, in which social feasting gave rise to a domesticated grain, rather than a domesticated grain leading to the development of communal celebrations of eating and drinking.

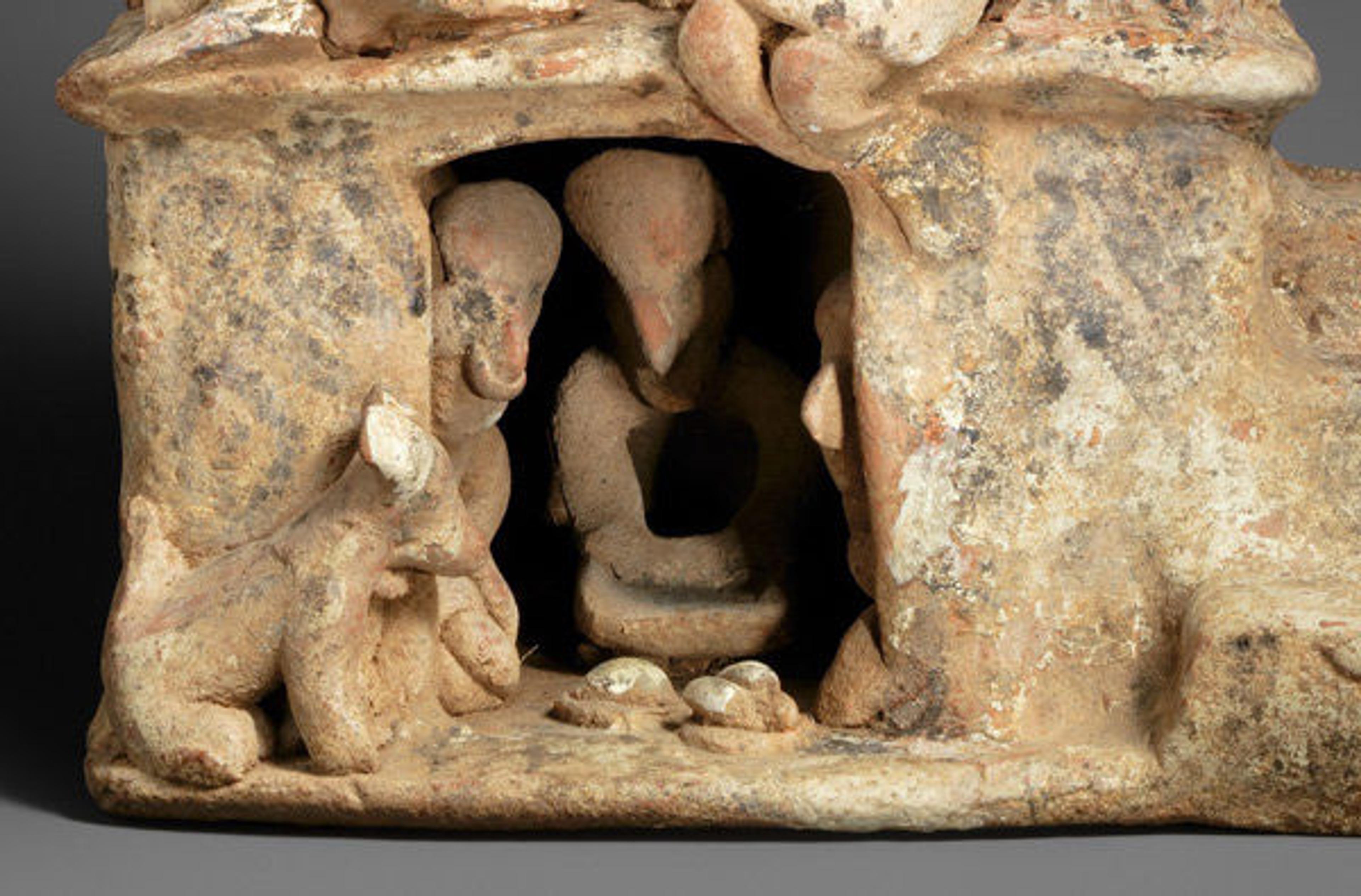

Regardless of the motivations of early corn propagators, it is clear that the earliest settled villages thrived off of maize and its products. In a house model from the early centuries A.D. currently on view in the exhibition Design for Eternity: Architectural Models from the Ancient Americas, we see a figure grinding corn in the lower recesses of a two-story building as others prepare tamales; a nearby dog intently watches the food preparation (fig. 2). The individuals depicted upstairs lounge about waiting for the work to finish below, or, judging by the full bellies of some of the figures, they are eager to have a second helping!

Fig. 2. House model (detail of individuals grinding corn), A.D. 100–300. Nayarit, Mexico, Mesoamerica. Ceramic; H.11 15/16 x W. 8 5/8 x D. 6 1/8 in. (30.3 x 21.9 x 15.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.359)

Maize was so important to the ancient Maya that the plant itself was personified in their consciousness as a deity, the ideal portrait of beauty (fig. 3). The ancient Maya modified the crania of their infants to create an elongated profile of their skull with a high, sloping forehead. This replicated the corn cob itself, the tassel-haired head of the maize plant. Artists showed the Maize God dancing, dripping with jade jewelry, and Maya kings and queens even impersonated the Maize God and his companions in courtly rituals while eating corn tamales and drinking a corn-based drink, atole.

Fig. 3. Left: Vessel with seated lord, 7th–8th century. Mexico, Mesoamerica. Maya. Ceramic, stucco; H. 9 1/2 x Diam. 7 3/8 in. (24.1 x 18.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1992 (1992.4). Right: Young Corn God, 8th century. Mexico, Mesoamerica. Maya. Ceramic, pigment; H. 8 1/8 x W. 2 x D. 1 1/2 in. (20.7 x 5.1 x 3.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.728)

From the earliest archaeological evidence of settled communities to the time of the Spanish conquest, it is clear that most societies in the ancient Americas valued periodic ritual feasts. Often these seem to have been linked with funerary celebrations, with large plates of food and massive quantities of chicha consumed and offered to the ancestors or the gods. Royal tombs were filled with eating and drinking vessels so the kings and queens would be amply fed in the afterlife. In the Moche cities on the north coast of Peru from the first millennium, tombs of the powerful contained thousands of vessels alongside whole llamas or alpacas, a key source of meat in South America (fig. 4). Many Moche vessels were made in the shape of fantastic buildings populated with human and supernatural characters, so that the deceased carried with them the power of architecture into the next world.

Fig. 4. Left: Architectural vessel, A.D. 200–600. Peru. Moche. Ceramic; Height: 10 13/16 in. (27.5 cm), Length: 7 1/16 in. (18 cm), Width: 7 1/16 in. (18 cm). Museo Larco, Lima (ML002893). Right: Architectural vessel, A.D. 200–600. Peru. Moche. Ceramic; Height: 8 7/16 in. (21.5 cm), Length: 7 11/16 in. (19.6 cm), Width: 5 1/2 in. (14 cm). Museo Larco, Lima (ML002901)

Societies in ancient North and South America engaged in feasts for some of the same reasons that modern peoples do: celebration of cycles such as the solar year, the lunar year, or the human lifespan; drumming up political support from allies or potential competitors; or honoring deities and religious phenomena according to traditions that transcended time and place. Feasts and celebrations were also a time for ancient American artists to shine as they prepared masterpiece works from which to eat and drink, and which served as offerings to authorities both in this world and in the spiritual realm. As curator Joanne Pillsbury points out, the dead were often the recipients of the artists' best works.

Feasting also encompassed more than eating and drinking: they were also hotbeds of fun and entertainment. Two of the works in Design for Eternity remind us that, in many ways, the celebratory activities of ancient peoples were just like those of us celebrating Thanksgiving this week, which include playing games and watching sports (fig. 5). Yupana stones from the highland Andes evoke the terraced and canaled landscape created by expert farmers on the slopes of deep valleys. A prevailing interpretation is that they are game boards, and like the rooks and castles in chess, they draw inspiration from architectural features. The spectacular Nayarit ball-court model from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art is full of players and spectators. One can almost hear the roar of the crowd and imagine that, once the game is completed, they head off to celebrate by eating and drinking according to custom.

Fig. 5. Top: Game board (yupana), A.D. 200–600. Peru. Recuay. Stone; Length: 10 5/8 in. (27 cm), Width: 9 1/4 in. (23.5 cm), Height: 2 15/16 in. (7.5 cm). American Museum of Natural History, New York (41.2/7879). Bottom: Ball-court model, 200 B.C.–A.D. 500. Mexico. Nayarit. Ceramic; Length: 5 1/2 in. (14 cm), Width: 8 in. (20.3 cm), Height: 13 in. (33 cm). Los Angeles County Museum of Art, The Proctor Stafford Collection, purchased with funds provided by Mr. and Mrs. Allan C. Balch (M.86.296.34)

References

Lau, George F. Andean Expressions: Art and Archaeology of the Recuay. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2011.

Mann, Charles. 1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus. New York: Vintage Books, 2005.

Pillsbury, Joanne, Patricia Joan Sarro, James Doyle, and Juliet Wiersema. Design for Eternity: Architectural Models from the Ancient Americas. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015.

Piperno, Dolores R. "The Origins of Plant Cultivation and Domestication in the New World Tropics: Patterns, Process, and New Developments." In Current Anthropology 52, no. S4 (Oct. 2011): S453–S470.

Smalley, John, and Michael Blake. "Sweet Beginnings: Stalk Sugar and the Domestication of Maize." In Current Anthropology 44, no. 5 (Dec. 2003): 675–903.

Webster, David L. "Backwards Bottlenecks." In Current Anthropology 52, no. 1 (Feb. 2011): 77–104.

Related Links

Design for Eternity: Architectural Models from the Ancient Americas, on view October 26, 2015–September 18, 2016

Now at the Met: "The Drinking Cup of a Classic Maya Noble" (September 25, 2014)