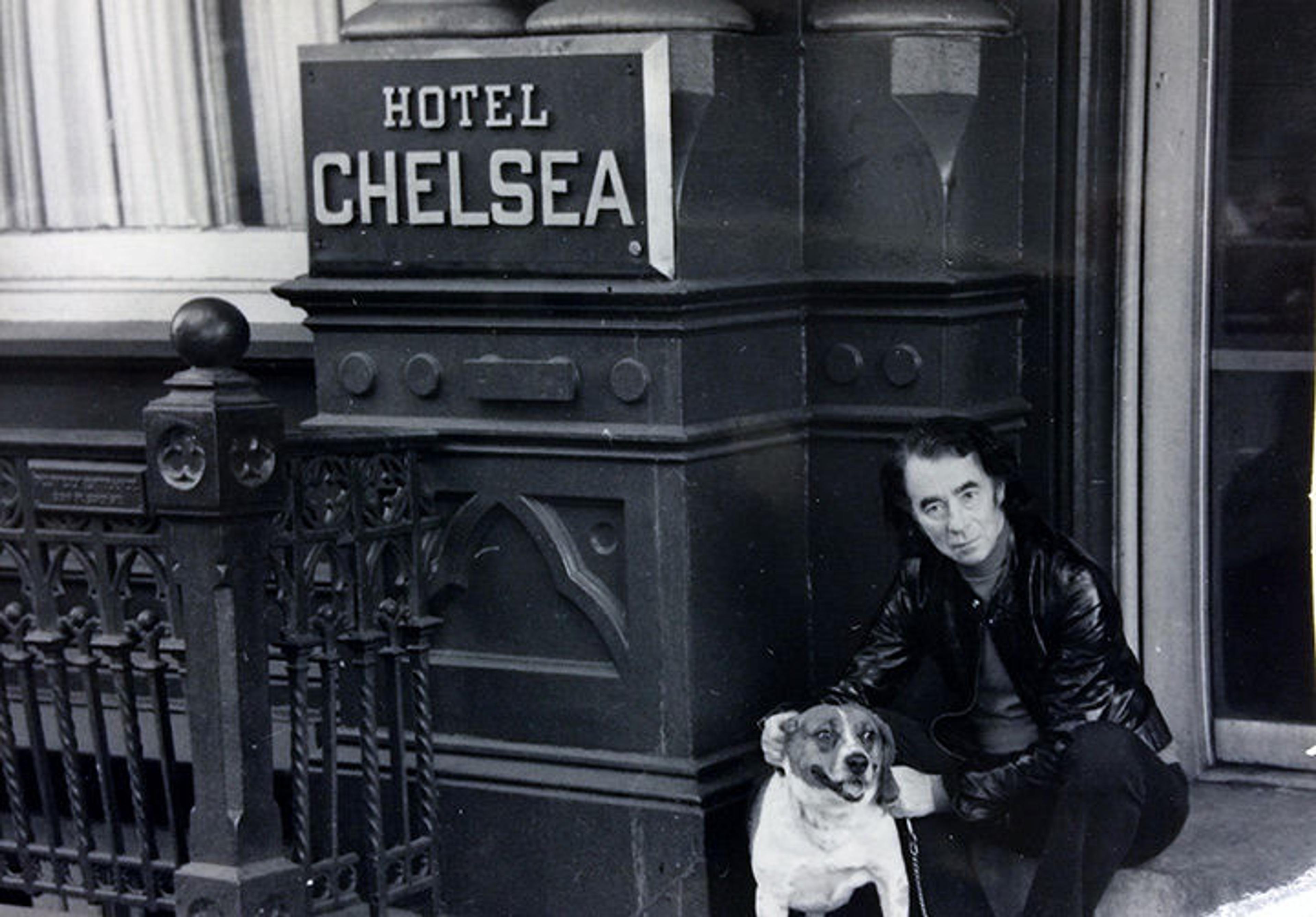

Charles James and his dog Sputnik, circa 1975, in front of the Chelsea Hotel. Photo by Barbara Walz. Photo from the Charles James Papers

For the next year, two archivists are arranging, describing, and rehousing the papers of Anglo-American couturier Charles James, with the goal of making them easily usable by scholars, graduate students, designers, and others interested in studying the James legacy. This blog series gives a behind-the-scenes look at the project's progress.

«During the peak of his design career, from roughly 1920 to the 1950s, the couturier Charles James lived and worked in the centers of fashion (London and Paris) and industry (Chicago, home of his mother's family). New York is where he kept returning, however, spending time there as early as 1928, long before it was a fashion capital on the scale of London or Paris. Perhaps no home of his was more fitting than the place he lived in New York after this design heyday, from 1964 until his death in 1978: the Chelsea Hotel.»

James's choice is unsurprising, as he had a habit of living in hotels, calling the Gladstone and 70 Park Avenue home before moving into the Chelsea. And, as outlined in the second post in this series, James also had a habit of self-mythologizing. What better rooms for such a person than those with a mythology of their own? A hotbed of creativity in the 1960s and '70s, the roster of the Chelsea's residents was a who's-who of the New York arts scene, playing host to everyone from Dylan Thomas to Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin to Patti Smith, Jimi Hendrix to Leonard Cohen, Sid Vicious to Simone de Beauvoir, and Arthur C. Clarke to Arthur Miller.

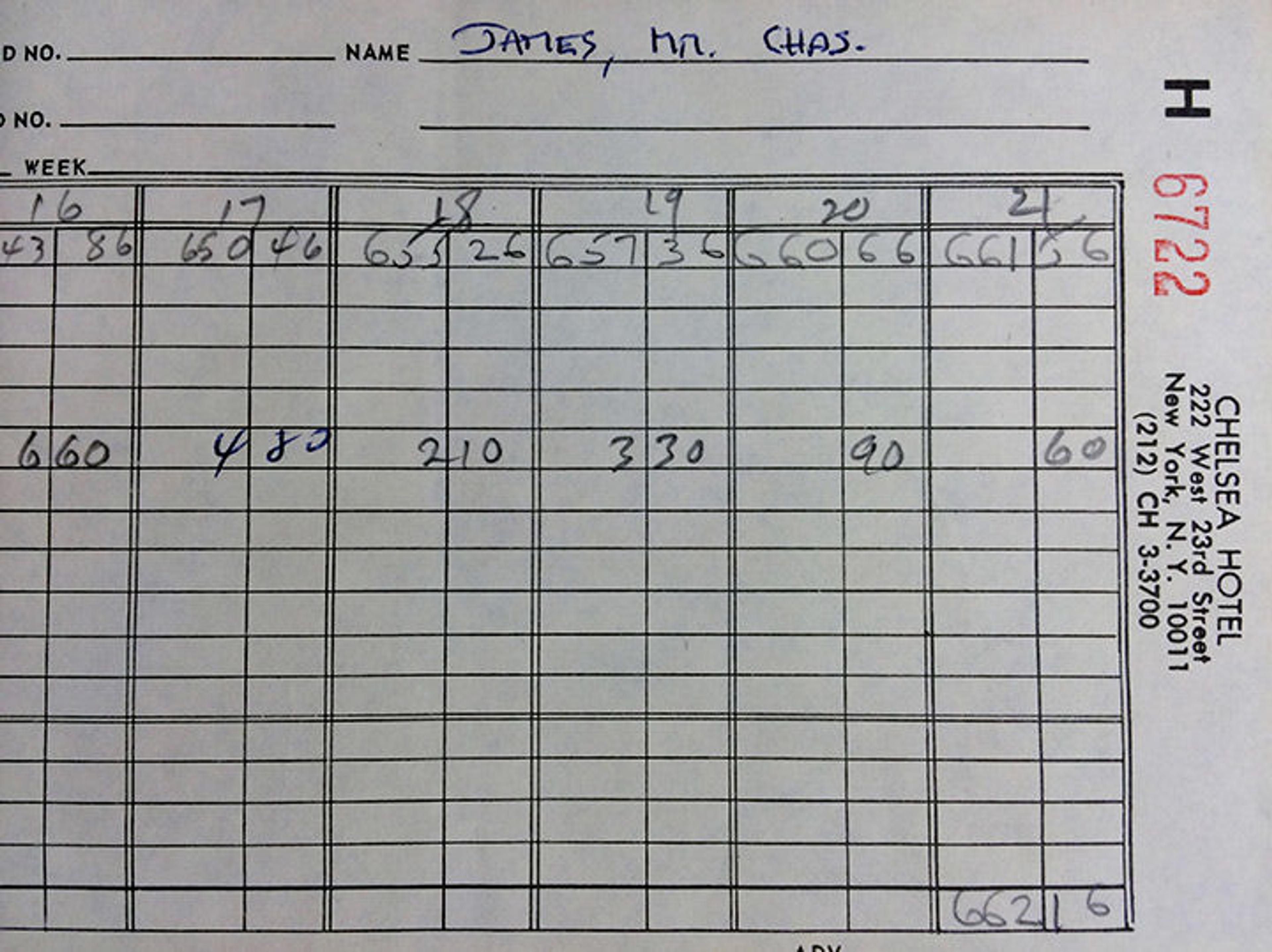

Rent invoice from the Charles James Papers. Photo by the author

James was well aware of the Chelsea's roster of residents and its attendant reputation. He kept up a robust correspondence with Stanley Bard, the hotel's cherished second-generation building manager, who was known for cultivating creative tenants, sometimes giving discounts or extensions on rent if he believed in their talents. In exchange for such camaraderie, however, the place appeared to be in a chronic state of disrepair. James freely gave his opinions on both sides of the Chelsea coin—historic relevance versus physical squalor. In one of a plethora of unsent letters found in the James Papers, he wrote to Bard, "I think it NOT a good idea to allow tribes of water beetles to overun [sic] the hotel, and do nothing about it for months when brought to your notice. This morning after getting out of bed I noticed a really large water beetle climbing into it. I assure you I did not think it funny."

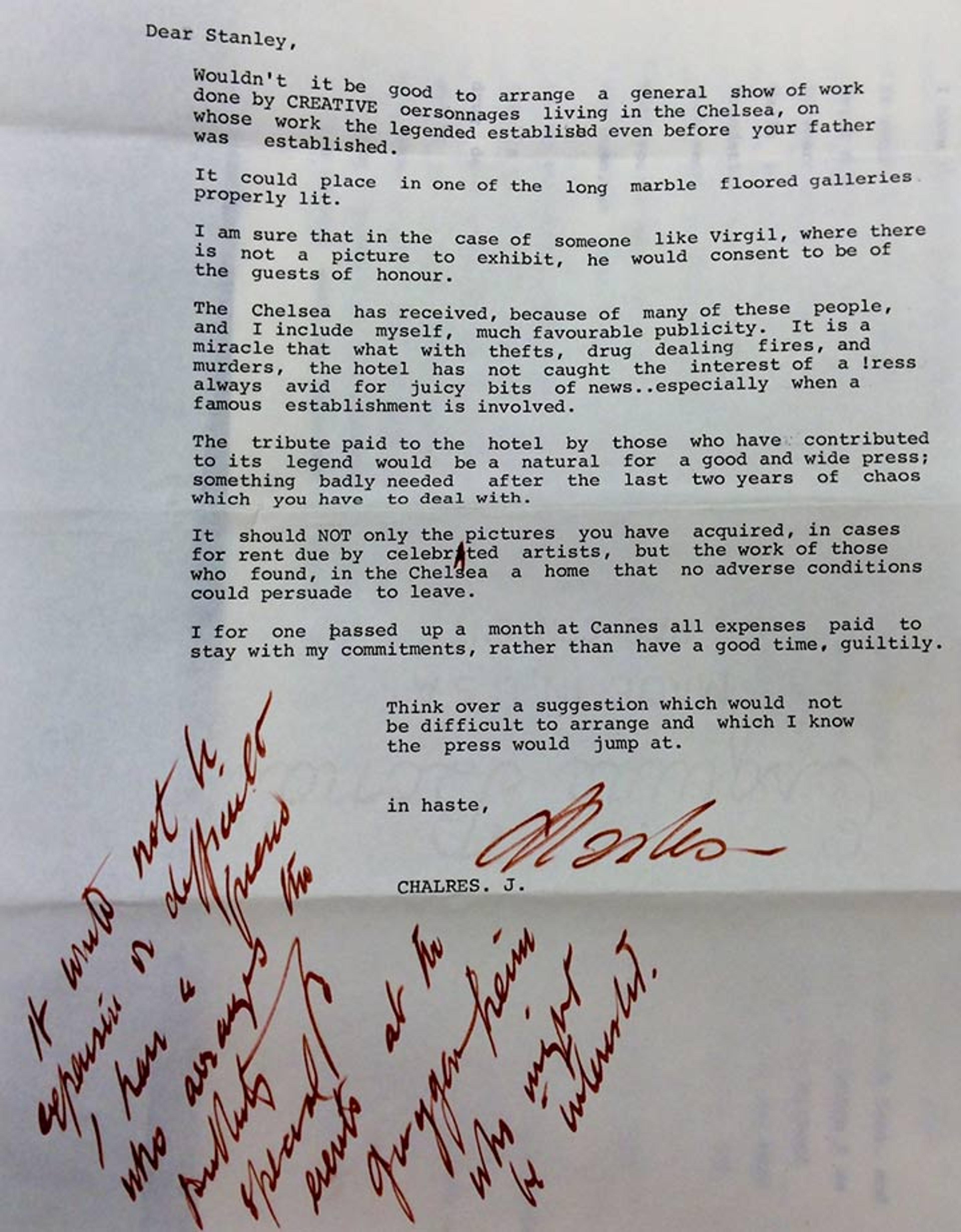

In another letter he complained of the seven weeks and counting he'd waited for the screen on his air conditioner to be replaced: "The result is that My Room is filthy dirty with neighborhood soot and all the papers I handle or/and leave around are a mess." (We archivists can attest to the truth of this claim.) In a 1973 letter, James described the Chelsea's double-sided reputation and proposed an art show, sure to elicit good press:

Letter from the Charles James Papers. Photo by the author

This letter represents many tendencies revealed in our processing of the papers so far: self-aggrandizement, both a courting and a denigration of the press, familiarity with celebrities and artists (the Virgil mentioned is composer Virgil Thomson), ambitious plans with an eagerness to see them done, and a dashing off of thoughts only to be proofread and perhaps corrected later.

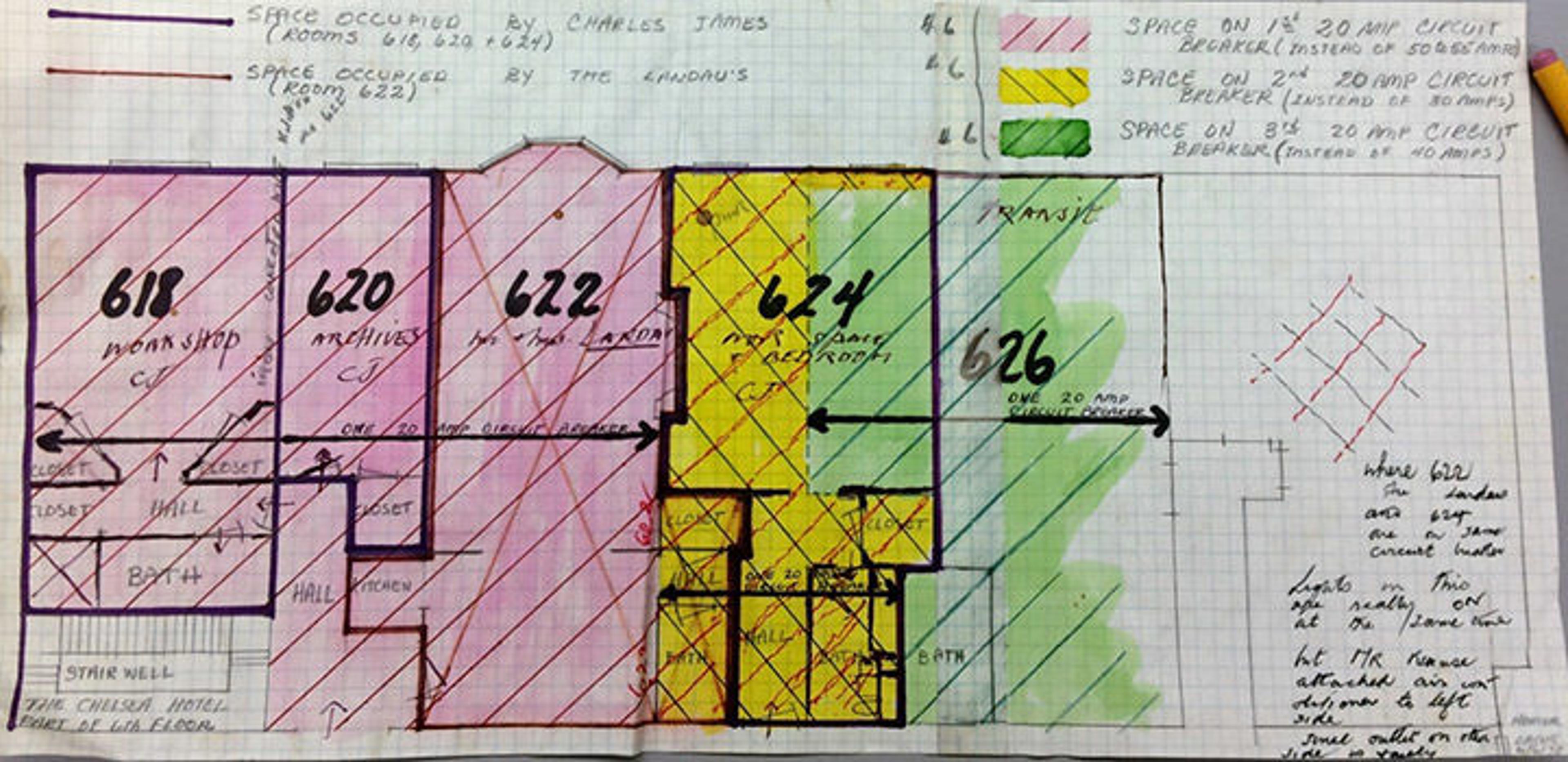

And what of this vast trove of papers, getting filthy dirty from the neighborhood soot? James's Chelsea rooms served as home, studio, workshop, and storage all rolled into one. We know that, whatever his arrangement may have been before, by 1978 he occupied three rooms on the sixth floor. His assistant Homer Layne (from whom The Met's Costume Institute acquired the James Papers in 2013) drew up the following floor plan for an electrical project, apparently involving the installation of, yes, an air conditioner:

Document from the Charles James Papers. Photo by the author

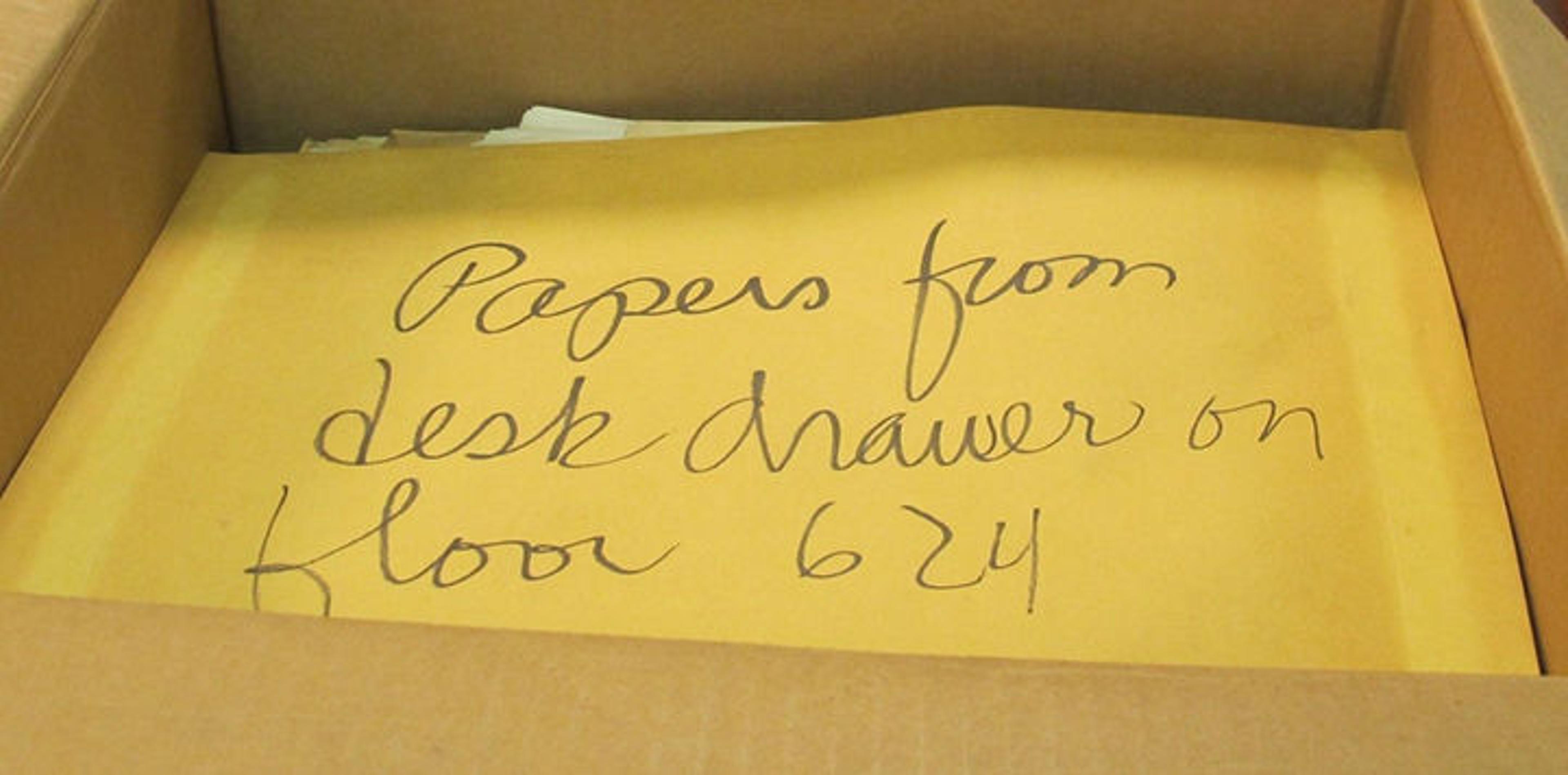

Room 618 is labeled "workshop," room 624 is "work space & bedroom," and room 620 is reserved for "archives." The latter is probably where James stored the documents (drawings, sketches, portfolios, etc.) that he was actively trying to donate to museums and like institutions. His other rooms, we know from photographs in the collection, were stuffed to the gills with bulletin boards, posters, plans, notes, instructions, clippings, and magazines. We saw how James perennially struggled to concoct an organizational scheme that would make this material accessible; it appears that the layout of the rooms themselves served as yet another organizing principle for this disorganized man, evident from how some material came packaged to the Museum:

Container at the intake of the Charles James Papers. Photo by Julie Lê

Among the minutia that James collected and kept were receipts for personal purchases from local businesses. As we organized them, we wondered how the picture that was forming of 23rd Street in the 1960s and '70s differed from the same area today. One benefit of working with the collection here in New York is being but a few miles from where James originally amassed it, so we decided to put together a list of businesses and catch the C train downtown.

New York is innumerable things, but one thing it's not is static. As we expected, most of the businesses James frequented are no more. The numerous stationery supply stores, copy shops, liquor stores, office furniture sellers, and typewriter suppliers that created the character and streetscape of James's Chelsea are now replaced by burger joints, bicycle shops, movie theaters, and, in the case of the typewriter store, the Apple computer servicer Tekserve, which itself went out of brick-and-mortar business this year. Some storefronts are simply walled off, awaiting inevitable renovation.

To our surprise, we were able to walk into three of the shops on our list. London Terrace Cleaners still stands, the third and farthest laundromat that James patronized (leading to the pet theory that he had failed to pay his bills at the two that were closer). The New London Pharmacy is still with us, though now across the street from its location in James's time. Chelsea Florists, once called Merit Florists, is run by the same family.

Finally, back to the Chelsea, the last survivor on our list. Now closed to the public, its grand exterior is draped in scaffolding and dotted by only a few window air conditioning units, a sign of dwindling residents as its transformation into a luxury hotel (plus, according to recent buyout news, condominiums) continues. Though he once complained about those air conditioners, James was nothing if not committed to his home. Time moves frantically forward, but his papers provide an enduring window into the bygone realities of mythic 23rd Street and its palace.

View of the Chelsea Hotel from across 23rd Street. Photo by the author

Related Links

In Circulation: Caitlin McCarthy, "A Work in Process: The Charles James Papers" (February 17, 2016)

In Circulation: Caitlin McCarthy, "'Some System Should Have Been Devised': The Organization (and Disorganization) of Charles James's Archive" (July 13, 2016)