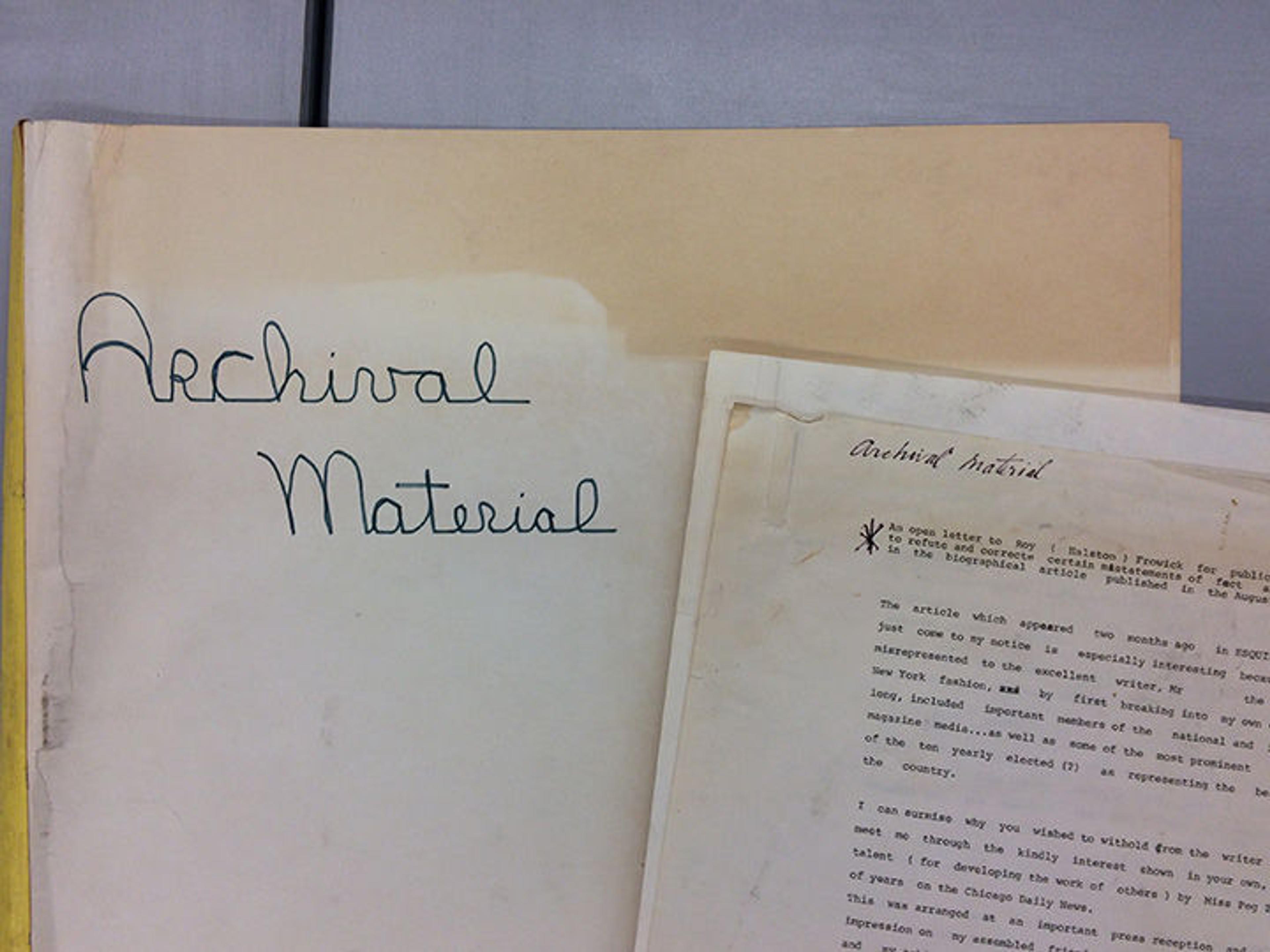

Document from the Charles James Papers. Photo by the author

For the next 17 months, two archivists are arranging, describing, and rehousing the papers of Anglo-American couturier Charles James, with the goal of making them easily usable by scholars, graduate students, designers, and others interested in studying the James legacy. This blog series, which began in February, gives a behind-the-scenes look at the project's progress.

«Most records are created and sorted organically in the daily activities of an individual or organization: correspondence filed alphabetically, for example, or bank statements filed by date. But occasionally there is an artificial aspect to a collection, an evident manipulation of the materials by the creator that the archivist must contend with.»

Enter Charles James. He is famous for his obsessive, creative, and idiosyncratic mastery of the elements of design, and it turns out that he was equally concerned with managing the records he created in this pursuit. James's efforts to organize, document, and preserve his own material output constitute one of the main narrative threads that has emerged as we process, and attempt to make sense of, the collection.

Containers at the intake of the Charles James Papers. Photo by Julie Lê

Containers at the intake of the Charles James Papers. Photo by Julie Lê

The Archivists' Conundrum

As we first emptied storage containers, there seemed to be no discernible order to what we were seeing. An often useful first step in revealing the structure of an unprocessed collection is to organize the materials into personal and business categories. For James, however, the business was personal, and the personal was business, so this proved an unhelpful strategy. People tend to create and organize their records as time passes, so we looked for a chronological progression, only to be frustrated by James's compulsion for photocopying. The same letter from 1964 popped up in boxes full of material from other years and decades, for example. What was going on here? As we continued to dig into the man and his material, meaning gradually emerged.

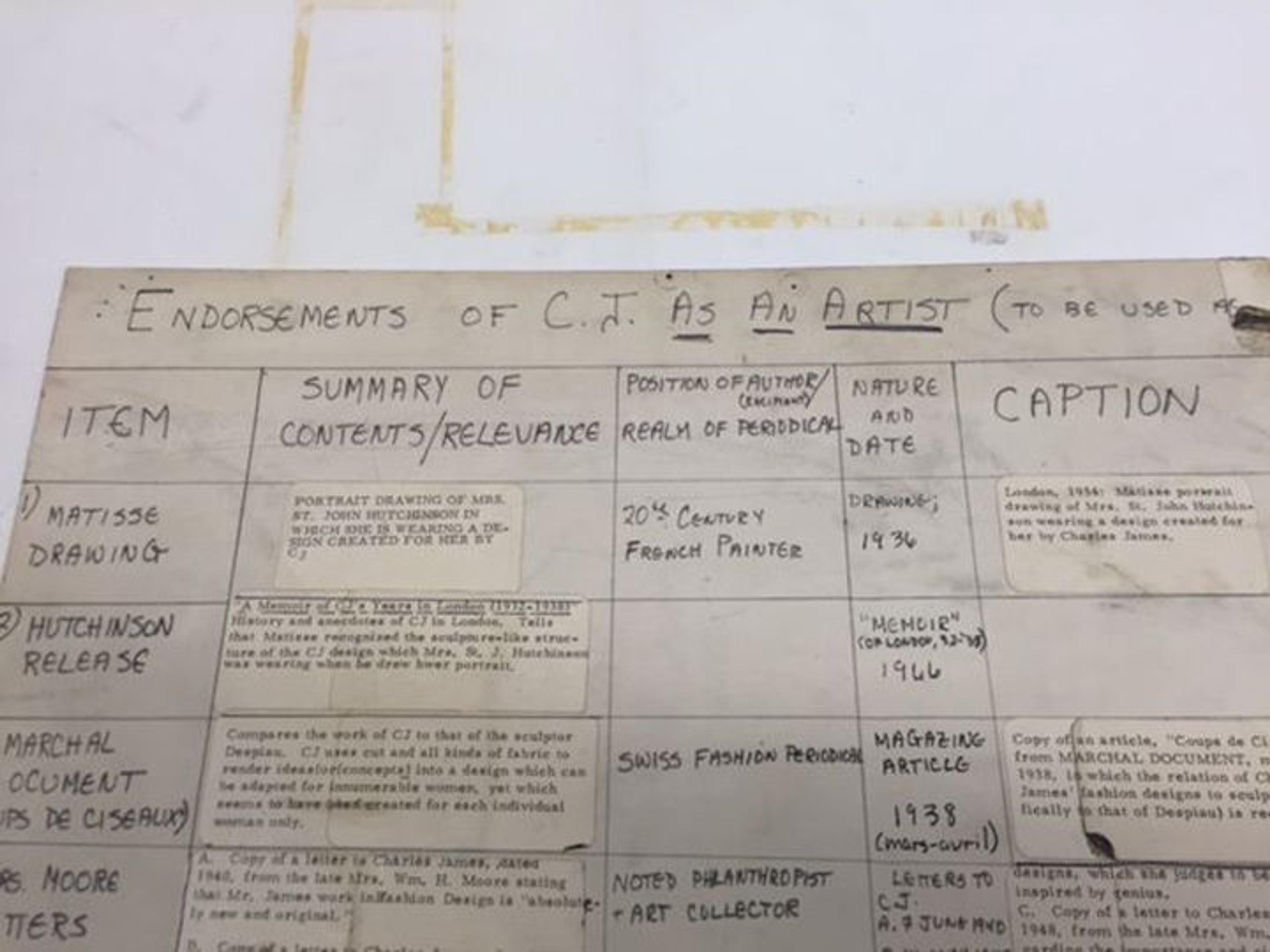

Chart from the Charles James Papers. Photo by the author

James as Artist

Referring to himself as an artist, sculptor, and engineer, rather than as a designer, James was intent on pushing his work and reputation beyond what he saw as the industry drudgery of Seventh Avenue and into the realm of fine art. Thus, securing a place for his work in museum collections and exhibition venues was paramount. He exhibited and donated garments (his artworks) to museums and galleries, and as early as 1957 James was also considering the complementary value his records presented, writing in a letter to patron Rodman de Heeren, "I want to have my records preserved . . . I have a feeling that with my work spread out in museums, they might one day become of interest to many."

File folder from the Charles James Papers. Photo by the author

Self-Definition of Records

What did James mean when he referred to his "records"? Certainly not the massive amounts of work notes, financial and legal documents, and sent and unsent correspondence that make up the bulk of the papers we are currently processing. His definition was more exclusive than ours, referring to that material most closely related to his clothes making and his design reputation: sketches and drawings (by James himself and by the fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez); curricula created for design-studies programs, including three-dimensional, sculptural forms; correspondence with luminaries of the art and fashion world; and press clippings documenting his talent for a public audience.

Sketches from the Charles James Papers. Photos by the author. Copyright © Charles B.H. James and Louise D.B. James

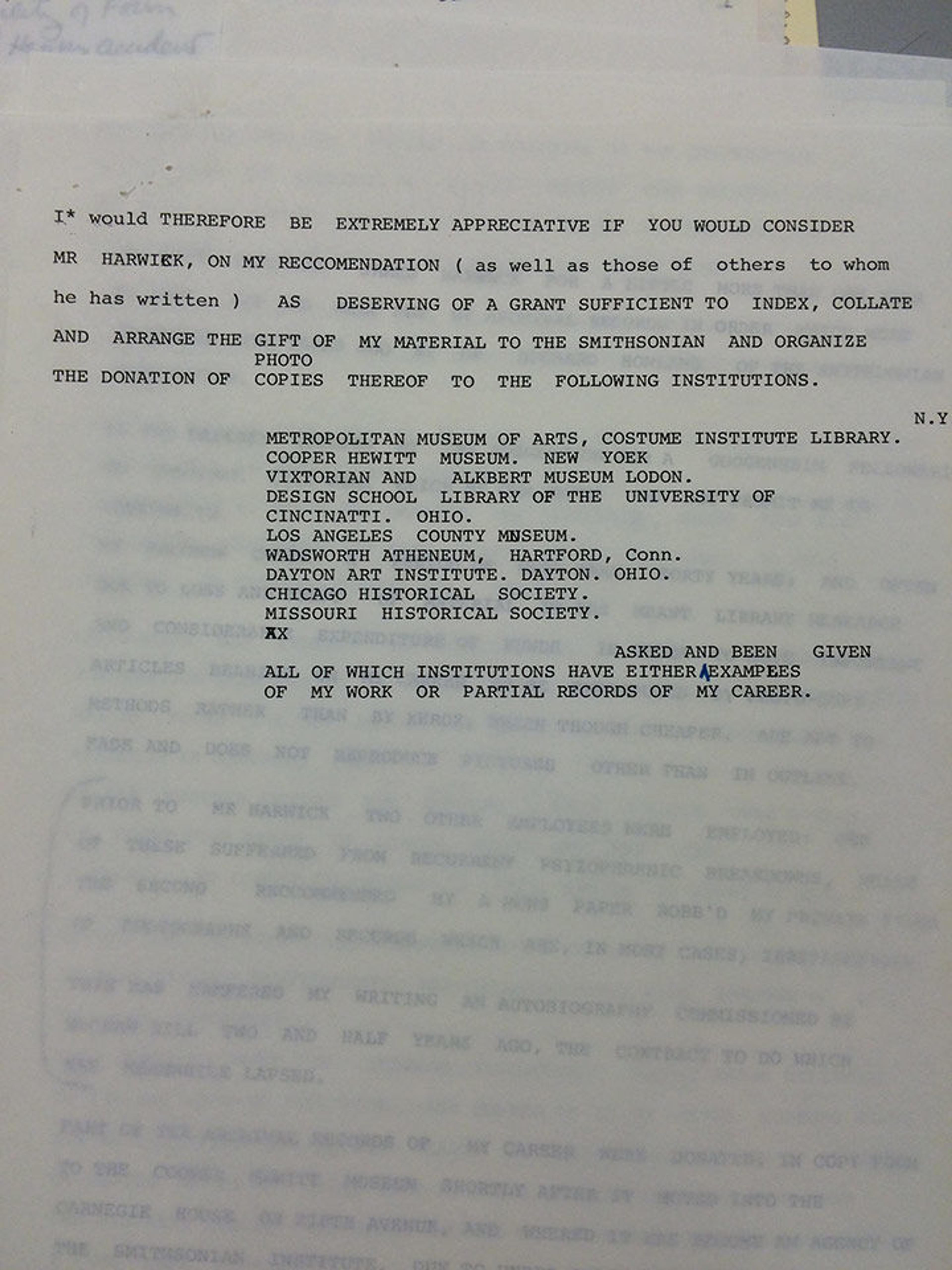

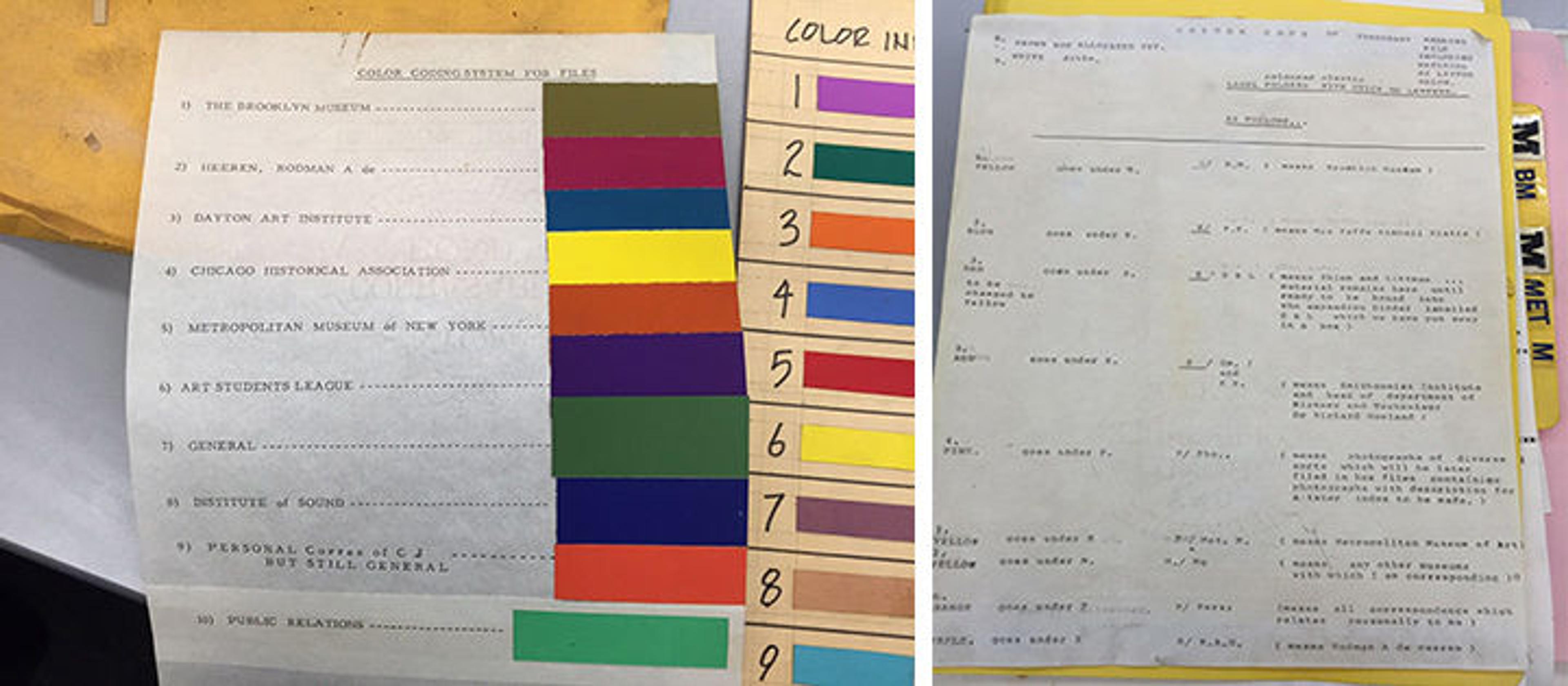

Here is the key to the conundrum: James started making real efforts to see his "archive" given to an institution in 1968, after receiving interest from Richard Howland, the special assistant to the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. He drew up lists of the museums, design schools, and historical societies that would receive a duplicate version of his accumulated documentation (see photo below), sending off copies of the Howland letter as proof that his archive was valuable.

What we archivists first considered to be an incoherent and disorganized collection of material turns out to actually be the sum of James's efforts to prepare and distribute a coherent archive. James may have had all of the will in the world, but he routinely, repeatedly, and sometimes spectacularly failed to find a way to achieve his goal.

Letter from the Charles James Papers. Photo by the author

Wrangling Records, and Assistants

At least two of his many office assistants were given the specific task to prepare James's archive. One, James Harwick, Jr., applied for (but was not granted) a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation in 1973. On the application he describes the project's title as "archivist for designer Charles James," and the field, "documentation of material." Another, Homer Layne—a design student, James's eventual executor, and donor of this collection to The Costume Institute at The Met—is referred to as "Acting Custodian of [James's] Archival Records" in a 1976 memo to Fashion Institute of Technology Library Director John Touhey.

Material from the Charles James Papers. Photo by the author

Harwick and Layne were just two of the numerous assistants and students James employed, who were often mercilessly tasked with keeping his ever-burgeoning records in order. Even in a fallow design period, such as he entered during the final two decades of his life, James and his team produced an impressive amount of paper. He was forever wrangling mountains of files and documents, trying to institute new storage and organization methods to handle his prolific output of drafts, notes, plans, letters, and other material.

Letter from the Charles James Papers. Photo by the author

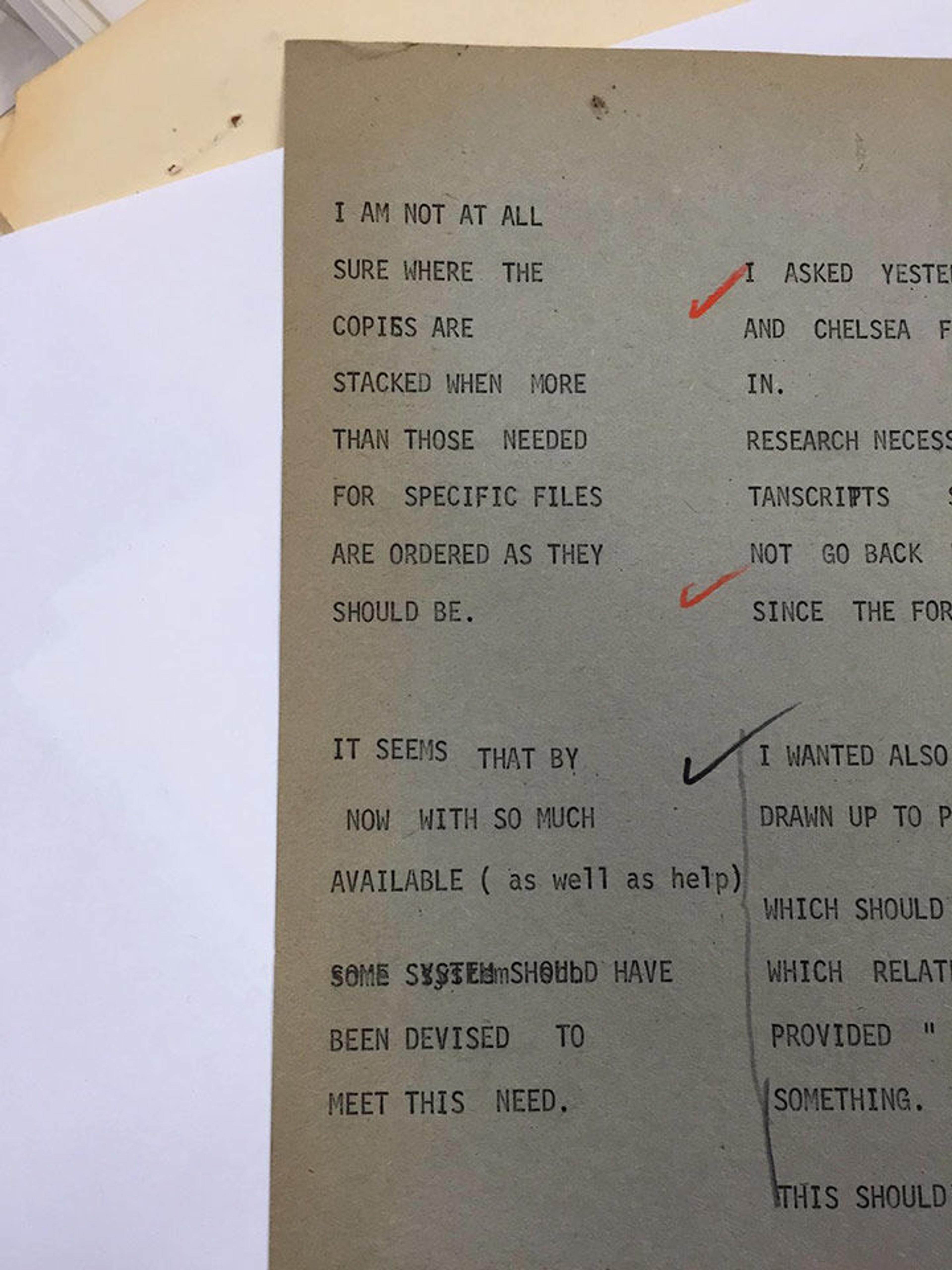

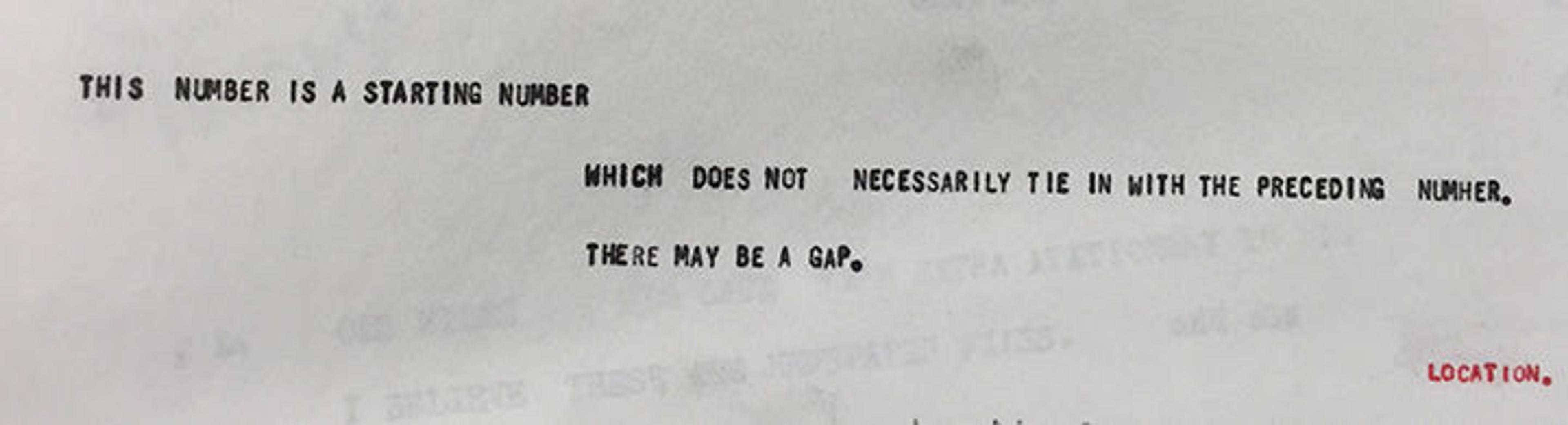

Recognizing James's repeated attempts to collate his records was the breakthrough we needed. With this awareness, we're now able to track his assistants' valiant efforts using three helpful signs: handwriting; the type of office supplies used; and, of course, the organizational systems employed. These schemes boggle an archivist's mind. Some are color-coded; others, a sequence of letters or numbers that often don't follow a sequence or are incomplete.

Many systems were devised to deal with documents in limbo—"to-be-filed" files. And within a scheme, conventions are often arbitrary, with letters arranged intermittently by correspondents' first or last name, for example, or filed under "M" for "Meeting at FIT." The systems appear to have been most often invented by James, who then wrote extensive, sometimes scathing notes to his revolving cast of office assistants detailing how to do the impossible.

Documents from the Charles James Papers. Photos by the author

Finishing the Job

Thanks to James's early and continued efforts to have his work held by major art institutions, and his large network of clients-cum-donors, many of his garments and drawings are found today in the collections of major institutions including The Met, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Victoria & Albert Museum, Chicago History Museum, Rhode Island School of Design, and the Arizona Costume Institute, among others. And his true archive, not just the subsection of "Very Important Persons" correspondence and fashion sketches he prioritized, but all of the mountainous remainder, rests with us. It may not be a conventional collection, but we have in our hands James's last design, unfinished: the records that tell his story and secure his legacy. He just needed some professional help.

Instructions from the Charles James Papers. Photo by the author

Related Links

In Circulation: Caitlin McCarthy, "A Work in Process: The Charles James Papers" (February 17, 2016)