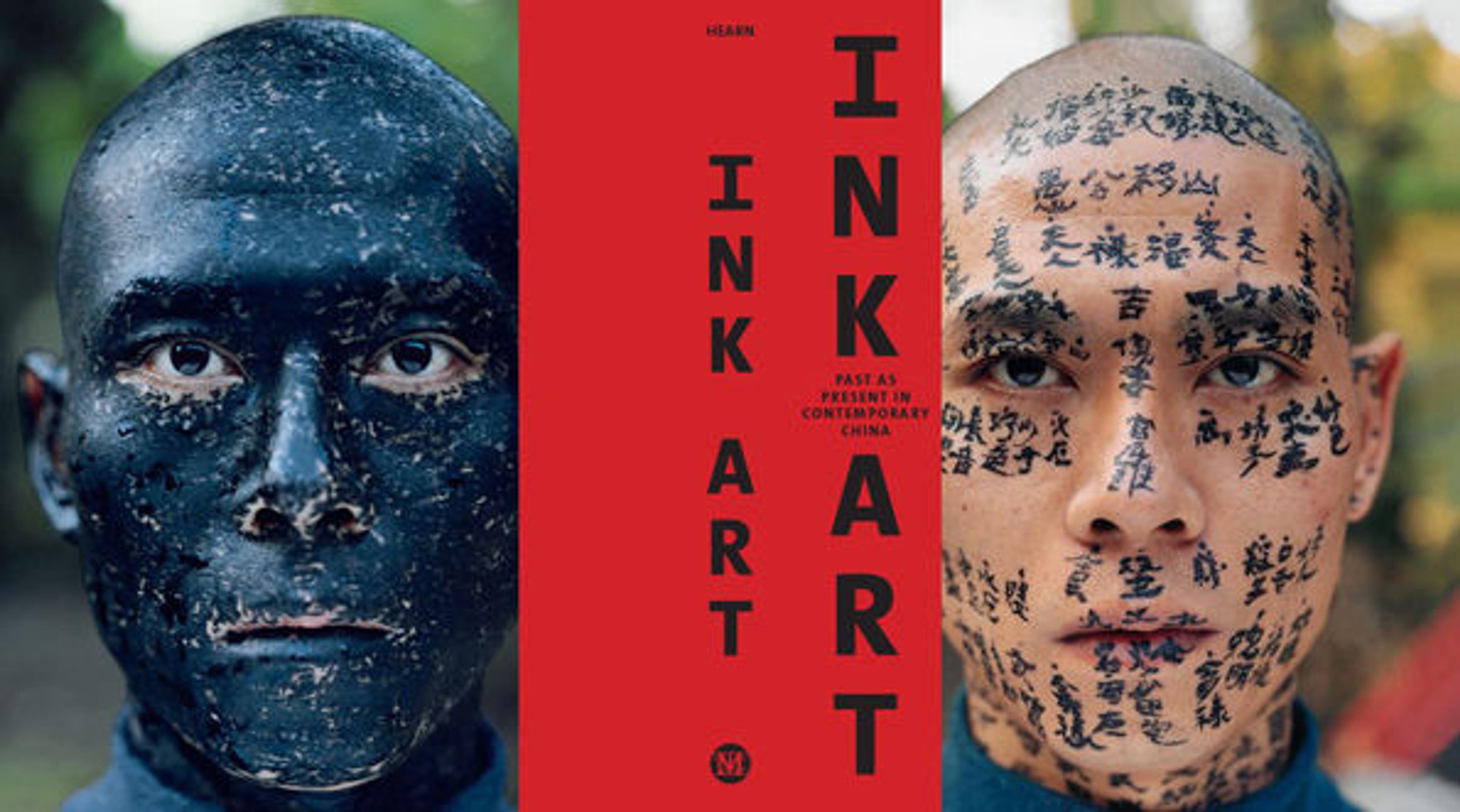

Featured Catalogue—Interview with the Curator: Mike Hearn

Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China, by Maxwell K. Hearn with an essay by Wu Hung, features 250 illustrations in full color and is available in The Met Store.

«I recently had the opportunity to speak with Mike Hearn—the Met's Douglas Dillon Curator in Charge of the Department of Asian Art—about his work in authoring the catalogue accompanying the upcoming exhibition Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China, his inspiration for incorporating modern works into his department, and the role of the Chinese artist in today's art world.»

Nadja Hansen: Your past books have focused on traditional ancient Chinese art and culture. What compelled you to write, for the first time, about contemporary art for the Ink Art catalogue? Was there a particular artwork, book, exhibition, or conversation that inspired you?

Mike Hearn: The first piece of contemporary art [the Met's Department of Asian Art] purchased was a scholar's rock made of stainless steel by Zhan Wang. I had admired a similar piece at a friend's home in Beijing. It struck me as an interesting juxtaposition to our collection of other traditional scholar's rocks, and would have the effect of bringing the past into the present.

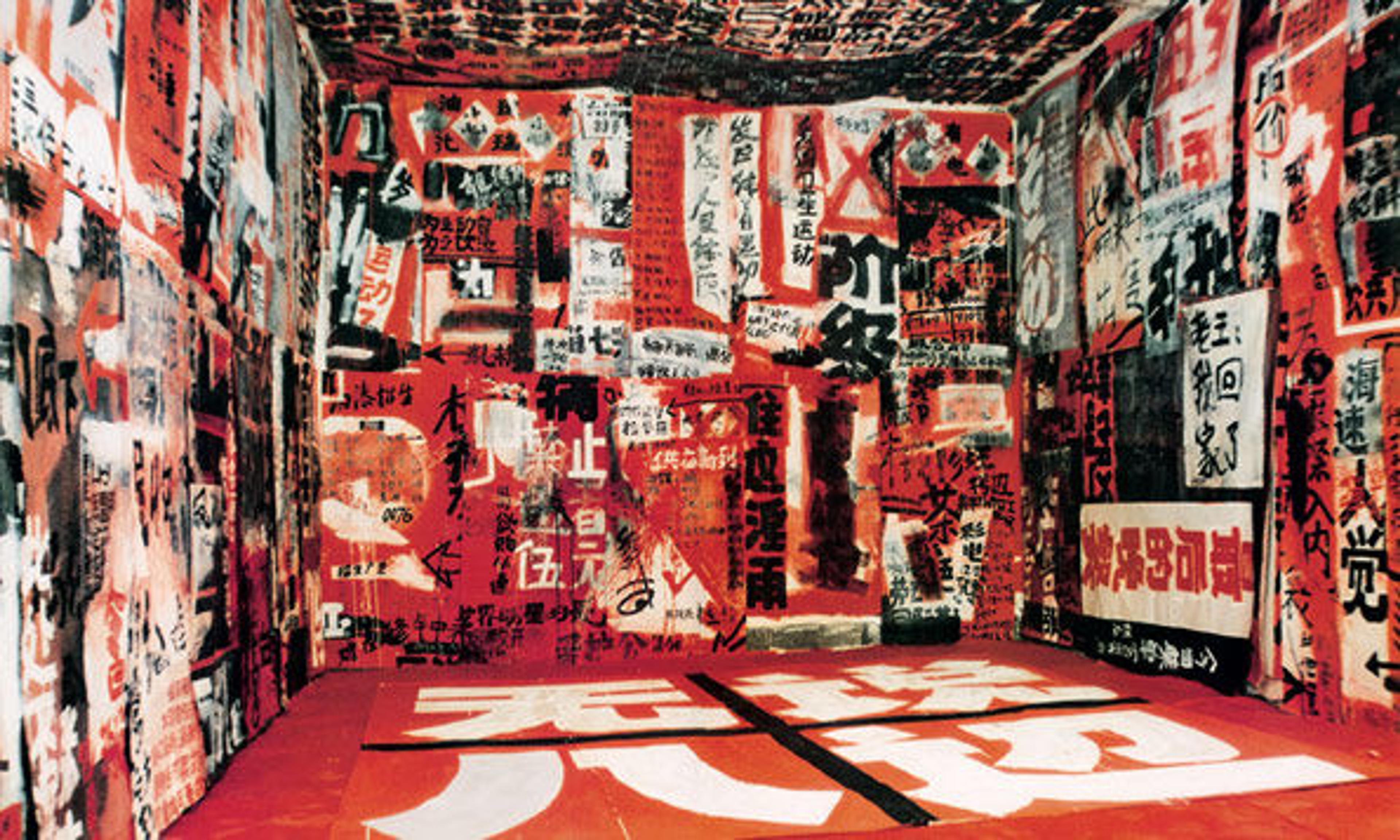

Wu Shanzhuan (Chinese, b. 1960). Red Humour Series—Today No Water; also known as The Big Characters (dazibao), 1986. Multimedia installation; dimensions variable. Installation view at the artist's studio and Institute for Mass Culture, Zhoushan

Then in 2006 I went to the first auction of contemporary Chinese art at Sotheby's, and was struck by the diversity and quality of some of the pieces. I realized that there were contemporary works of Chinese art that resonated with me, but I wasn't sure that they would have had the same effect on my colleagues in the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art. Prior to that time, I had always thought that modern and contemporary art was their responsibility, but this experience made me realize that there are fantastic contemporary Asian works that would resonate more meaningfully in our galleries than in a Western modern-and-contemporary gallery space.

That same year I borrowed a piece by an artist named Wang Dongling that had been sold in the Sotheby's auction. I put it in an exhibition of Chinese calligraphy with much older art, realizing that while Westerners can't read Chinese calligraphy, they can read conceptual art. The tools for appreciating calligraphy aesthetically—seeing it as gestural art with dynamic figure-ground relationships and contrasts of positive and negative line and space—was already in people's repertoire, they just needed permission to use them. So I put this piece from 1999 next to calligraphy from 1099. I loved the reaction. I had a Chinese reporter come in and say, "How can Westerners appreciate this? They can't read it!" I then took him to the contemporary piece and explained that it is not necessary to be able to read something in order to appreciate it.

That experience gave me the idea that while ink art is something that is uniquely Chinese, the same skills and vocabulary are used to look at both Abstract Expressionism and Chinese calligraphy. There was this wonderful crossover.

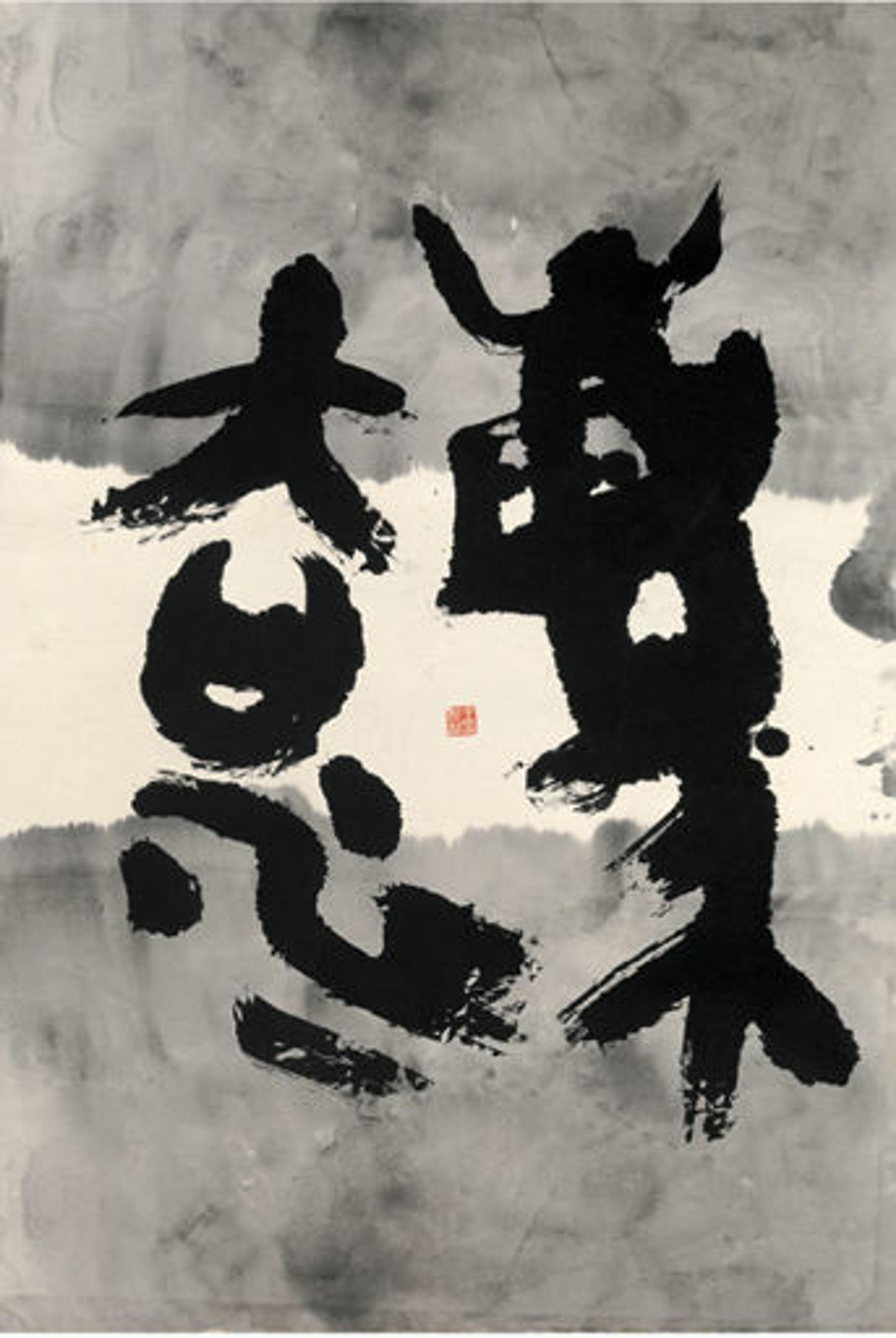

Left: Wang Dongling (Chinese, b. 1945). Canon, 1991. Ink on paper; 39 1/2 x 26 7/8 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Friends of Asian Art Gifts (2012.320)

Nadja Hansen: Did you collaborate with the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art on this exhibition? Do you see that being a trend in the future?

Mike Hearn: I haven't really collaborated with the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art yet, but now I hope to in the future—especially when it comes to acquisitions. I want to continue to collect works of art that will elucidate and extend our collection of Asian masterworks, but I don't ever want to transgress on initiatives that are being taken by our Modern and Contemporary curators. I want their buy-in, and I respect their opinions; they bring an international perspective to contemporary artwork, while I bring the Asian perspective.

A work of art is like great literature: You may be able to translate it into another language, but the indigenous language is where its spirit is expressed most clearly. The language of art is its style, and when it comes to Chinese artworks, I can read that style in its original language. That is what I bring to the table, which is something that Modern and Contemporary can't do in the same way. They speak a global stylistic language, while I speak the language of tradition. The only way to truly appreciate art is to see it in different contexts. That is what having an encyclopedic collection at the Met enables us to do: see art from varied perspectives—global and specific. There are no specialists in modern art in the Asian art department, but we have the capacity to get excited when we see something contemporary that makes sense to us. It is this diversity of points of view that gives the Met a unique capability to put contemporary art into varied historical and geographical contexts.

Song Dong (Chinese, b. 1966). Printing on Water (Performance in the Lhasa River, Tibet, 1996), 1996. Thirty-six chromogenic prints; each 23 3/4 x 15 3/4 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Promised Gift of Cynthia Hazen Polsky (L. 2011.70.6)

Nadja Hansen: Were you afraid of push back or criticism from traditional Asian art scholars, or from fellow colleagues in Modern and Contemporary Art?

Mike Hearn: I was so excited about the project that I didn't think of it as taking a risk. It was more that I was stretching myself. This exhibition is simply my response to what is happening in the contemporary art world. I wanted to look at modern Chinese art from my traditional perspective, but I didn't want to include artists who are merely continuing traditional idioms; I wanted to discover artists who are extending, challenging, or subverting tradition. So I began to look beyond works of ink on paper, expanding to photography, video, oil on canvas—really anything that retained what I call the "ink aesthetic."

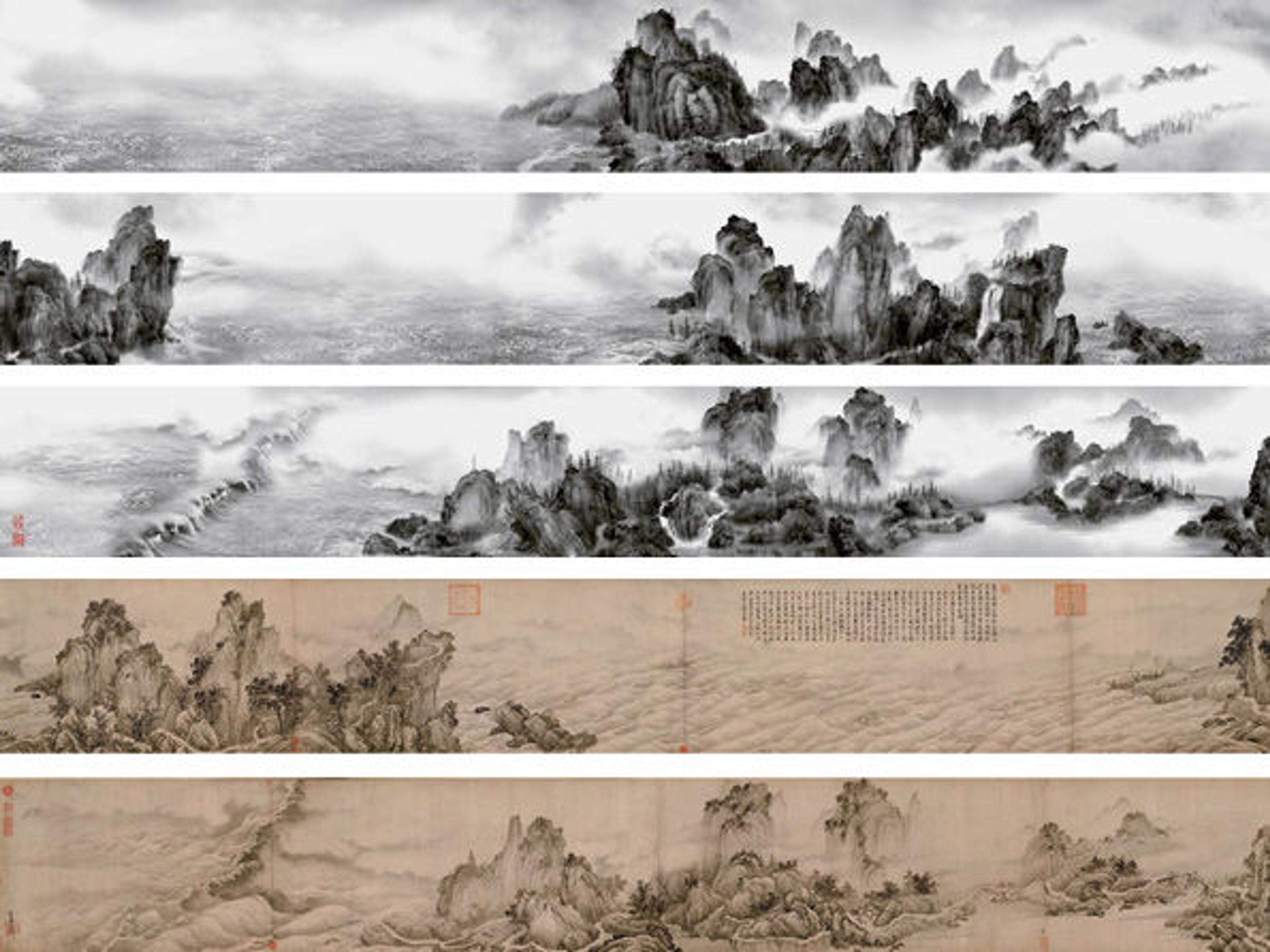

For example, I have been thinking for a long time of doing an exhibition on the Guo Xi tradition—Guo Xi being an artist who lived from around 1000 to 1090. I had encountered a nearly white canvas by the contemporary painter Qiu Shihua, with only the faintest hint of a landscape veiled in mist, and I immediately felt a connection between this work and the atmospheric paintings of the Guo Xi tradition. Qiu works in oil on canvas, Guo Xi worked in ink on silk, but for me there was an unmistakable spiritual resonance between the modern artist and the ancient master.

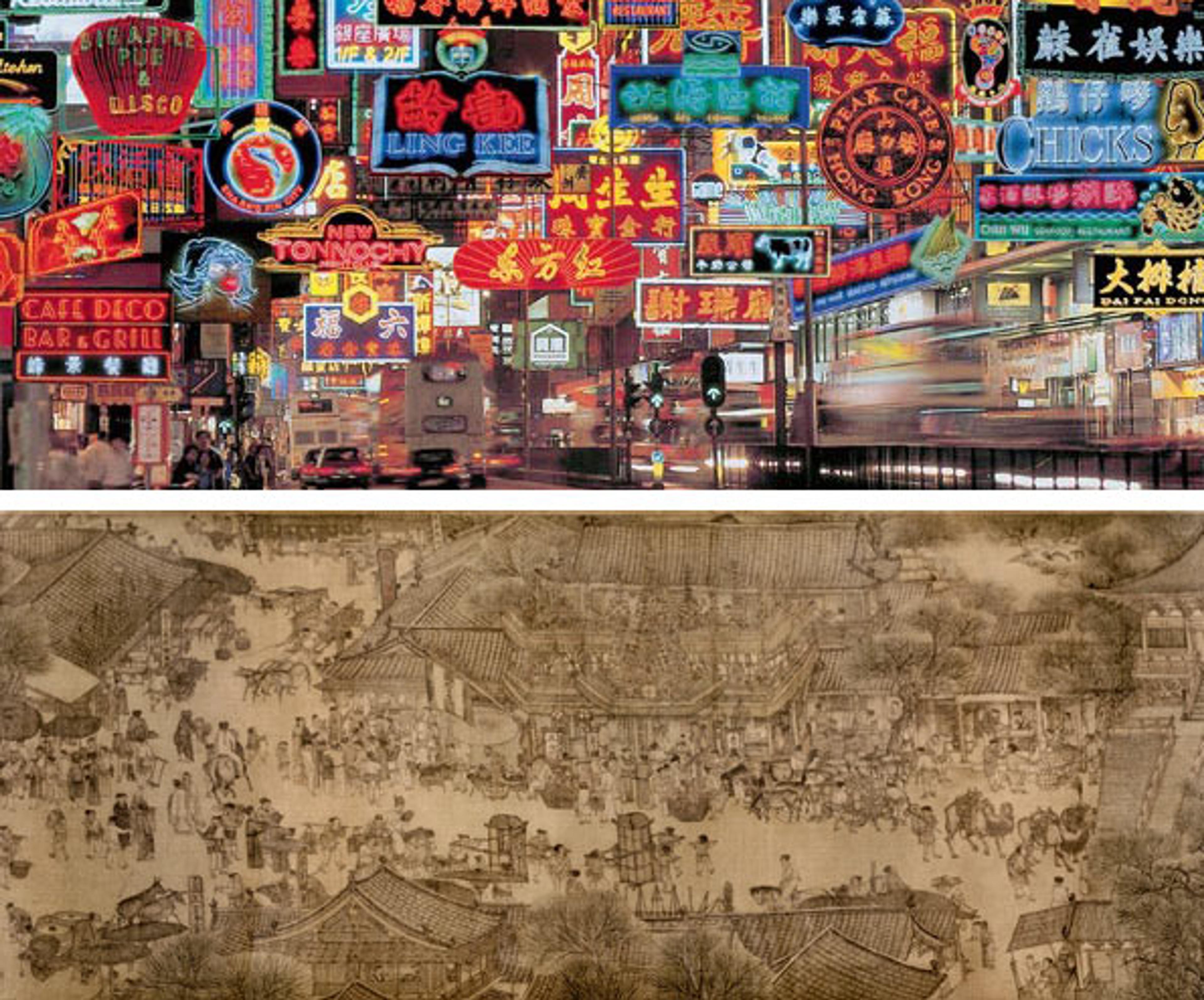

Top: Yang Yongliang (Chinese, b. 1980). View of Tide, 2008. Inkjet print; 17 3/4 in. x 32 ft. 9 3/4 in. M+ Sigg Collection, Hong Kong. Bottom: Zhao Mengfu (Chinese, 1254–1322). Ten Thousand Li of Yangzi River, Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279). Ink on paper; 17 3/4 in. x 32 ft. 6 3/4 in. The Palace Museum, Beijing

Nadja Hansen: You label the exhibition and catalogue Ink Art, even though it covers so many other mediums. Why do you specifically emphasize the ink-art tradition?

Mike Hearn: Today's Chinese art is unprecedented in its diversity, but this exhibition only seeks to illuminate one segment of what's being produced—the portion that seems to be meaningfully informed by China's history of artistic traditions. There is no other culture with the same artistic continuity as the Chinese, and ink art, particularly calligraphy, has a lot to do with this phenomenon. There is really nothing equivalent in the West.

For centuries, a person was judged by his skill as a calligrapher. The same writing instrument, a supple-tipped brush, was also used to create paintings. In both cases, the text or imagery was often deemed secondary to the expressive power of the brushwork, and a key component of good brushwork was the ability to incorporate and creatively transform references to earlier stylistic models—the way a musician might riff on an earlier melody.

Today, everyone uses computer keyboards or ballpoint pens; there has been an enormous loss of something that was fundamental only one hundred years ago. And while millions of Chinese do calligraphy as a hobby in the same way as Winston Churchill painted watercolors, calligraphy for these people is no longer a vocation but an avocation. I'm not interested in practitioners who merely sustain a traditional practice. Rather, I am excited by those artists that grapple with finding new expressive content in these ancient traditions.

In their scale and gestural dynamism, Wang Dongling's contemporary pieces are surely inspired in part by the example of Abstract Expressionist works, but Wang has a calligraphic technique that Kline or Motherwell did not. His abstraction comes from a totally different place: two thousand years of brush writing techniques. Every turn and twist of the brush represents a technical facility that can still be appreciated from a traditional perspective.

Top: Keith Macgregor (British, b. 1947?). Neon Fantasy, Nathan Road (detail), 2002. Archival pigment print; 30 x 30 in. Bottom: Zhang Zeduan (Chinese, 1085–1145). Spring Festival along the River (detail), Northern Song dynasty (960–1127), 12th century. Handscroll, ink and color on silk; 9 3/4 in. x 17 ft. 4 1/8 in. The Palace Museum, Beijing

Nadja Hansen: In the catalogue, you compare the recent Chinese absorption and reinterpretation of Western philosophies and methodologies to what is also happening in the arts. Can you talk about some of the ways this is playing out artistically?

Mike Hearn: China is undergoing a sea change in economics, politics, and society. On the surface, it is embracing the culture of the West, whether it be in the form of Marxism, capitalism, consumerism, or commercialism. Artists are inevitably responding to these social changes by exploring earlier Western stylistic movements—Dada and Surrealism—that reacted to similar cultural and philosophical shifts in Europe and America. Such movements have now become as relevant to them as they were relevant here almost one hundred years ago.

So there is an exciting discovery by the Chinese of Western responses to changes in Western society. At the same time, there is an identity crisis: What is China? It may look Western, but scratch the surface and underneath you will find a tradition of philosophy and social norms that is completely different. It is inevitable that artists will rebel at some point against the imposition of a whole array of cultural influences—clothing styles, music, and consumerism—in order to seek out what is genuinely their own.

As Chinese artists become more sophisticated and knowledgeable about Western art, they seem to be increasingly comfortable about returning to their traditional roots. Artists who are discovering Western philosophy are also rediscovering Zen Buddhism and Daoism because their own ancient philosophies are part of what has influenced Western contemporary culture.

So "borrowing" is the wrong term—it is more about finding what is useful. We have to assume that Chinese artists are using both their own and Western traditions to solve new problems that they are posing for themselves. Truly great artists find a new way of thinking about a problem that is in front of them. In the future, we will see artists using a variety of cultural sources to solve the problems they are dealing with.

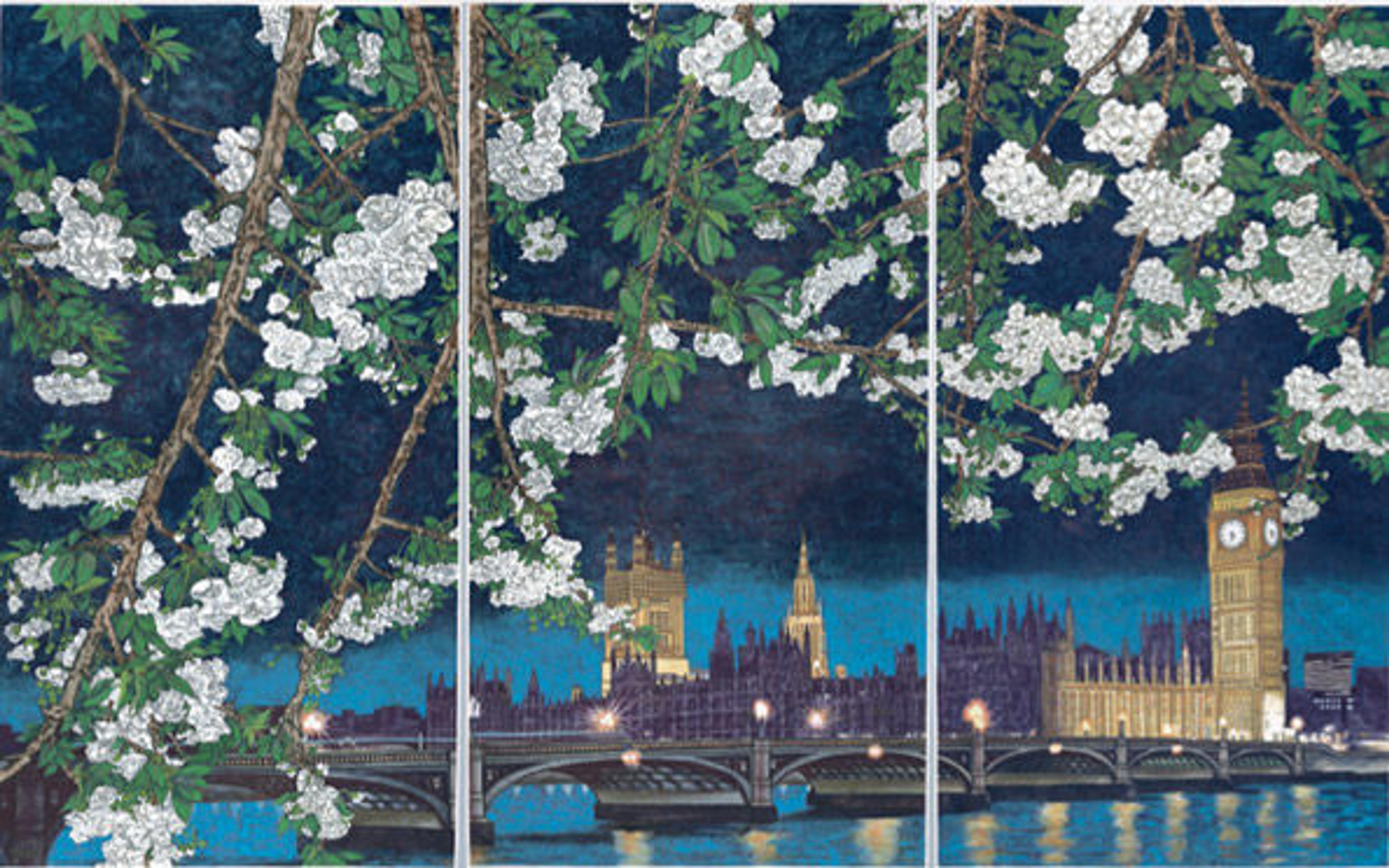

Yang Jiechang (Chinese, b. 1956). Crying Landscape LONDON, 2002. Triptych, ink and color on paper; 9 ft. 10 1/8 in. x 16 ft. 4 7/8 in. New York, private collection

Nadja Hansen: Contemporary Chinese art is relatively new to the global art market. Can you talk a little about the art world's reaction to this, and the new role of the "Chinese contemporary artist" within it?

Mike Hearn: Contemporary Chinese art has become a big business because certain styles appeal to Western tastes. The market really began in the West, and the Chinese artists that have been "discovered" now have to think about their "brand," and the most creative artists have to struggle with how to escape that box.

When a Chinese person comes to the West, they are labeled as Chinese. What does that mean? Each of these artists in their own way has to be asking that question: What does it mean to be Chinese? Am I a Chinese artist, or an artist who happens to be Chinese? Both are correct.

For me, it is an enormously moving opportunity to show the "Chinese-ness" of these artists. At the same time, I never want to negate that they are, first and foremost, artists. The works of art in this exhibition express a Chinese identity that needs to be appreciated and realized. That is what this is about.

Related Link

The Met Store: Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China

Nadja Hansen

Nadja Hansen was formerly an editorial assistant in the Editorial Department.