Renaissance Revival Room

Meriden, Connecticut, 1868–70

Cynthia V. A. Schaffner, Research Associate; Amelia Peck, Marica F. Vilcek Curator of American Decorative Arts; and Moira Gallagher, Research Associate

The Renaissance Revival Room, on view in Gallery 737, comes from the "princely mansion" built for Jedediah Wilcox (1817–1897) and his wife, Henrietta (1842/1843–1907). It once stood at 816 Broad Street in Meriden, Connecticut. A local entrepreneur and manufacturer of stylish hoop skirts, carpet bags, and other woolen goods, Wilcox commissioned Connecticut architect Augustus Truesdell (1810–1872) to design and superintend the building of the house between 1868 and 1870. This fashionable rear parlor, or sitting room, with its coordinating architectural details and richly ornamented decoration, includes its original suite of furniture. It speaks to the immense wealth Wilcox acquired through his various manufacturing enterprises in the years following the American Civil War.

The Renaissance Revival Room, on view in Gallery 737, comes from the "princely mansion" built for Jedediah Wilcox (1817–1897) and his wife, Henrietta (1842/1843–1907). It once stood at 816 Broad Street in Meriden, Connecticut. A local entrepreneur and manufacturer of stylish hoop skirts, carpet bags, and other woolen goods, Wilcox commissioned Connecticut architect Augustus Truesdell (1810–1872) to design and superintend the building of the house between 1868 and 1870. This fashionable rear parlor, or sitting room, with its coordinating architectural details and richly ornamented decoration, includes its original suite of furniture. It speaks to the immense wealth Wilcox acquired through his various manufacturing enterprises in the years following the American Civil War.

The Renaissance Revival Room

Setting

City of Meriden, Connecticut, 1875. Map reproduction courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library

Located halfway between Hartford and New Haven, Meriden, Connecticut, was settled in 1727 and became a town in 1806. Meriden's fast flowing Quinnipiac River helped to power early endeavors, but the widespread adoption of steam-powered engines for industry in the 1840s enabled the town to shift from a farming community to a booming manufacturing center. Meriden incorporated as a city in 1867, by which time its large woolen and metal factories were producing an unprecedented volume of goods, such as ladies' clothing and accessories, silver-plated wares, brass furnishings, and other innovative products for the American market.

Displayed on the center table in the room is a selection of silver-plated objects made in Meriden: a pitcher produced by the Meriden Britannia Company, a company founded by Jedediah Wilcox's brother Horace C. Wilcox (1824–1890), and a pair of goblets produced by Rogers, Smith and Company.

Displayed on the center table in the room is a selection of silver-plated objects made in Meriden: a pitcher produced by the Meriden Britannia Company, a company founded by Jedediah Wilcox's brother Horace C. Wilcox (1824–1890), and a pair of goblets produced by Rogers, Smith and Company.

Image: Meriden Britannia Company (1852–98). Pitcher. Meriden, Connecticut, ca. 1868. Silver plate, 12 1/2 x 10 1/2 in. (31.8 x 26.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Lent by the Meriden Historical Society, Meriden, Connecticut (L.1985.58.1)

Exterior of the House

View of the Jedediah Wilcox house, Meriden, Connecticut. Courtesy of Brian Cofrancesco

Architectural plans for the Wilcox House

Elevation for Design X, "A Norman Villa," in Samuel Sloan's Model Architect (1852, v. 1)

By the 1870s, architecture had emerged as a recognized profession in the United States; however, many of the nation's first well-known architects had to study abroad, since little to no formal training was available in America. Because of the scarcity of formally trained architects, it was common for local builder-architects, many of whom learned their craft in related enterprises such as carpentry, to copy designs and floor plans from published architectural pattern books. While one source reported that Jedediah Wilcox borrowed the architectural plans for the house from his brother Dennis Wilcox (1828–1886), who had an "imposing" home on nearby Colony Street, it is likely that Augustus Truesdell was inspired by designs featured in Samuel Sloan's well-circulated publications Model Architect (1852) and Sloan's Homestead Architecture (1861). Architectural historian Brian Cofrancesco, who has conducted extensive research into the Wilcox house, identified that its floor plan and exterior had many similar elements, including the massing of the facade and the small octagonal tower at the rear, to the plans and elevations for "A Norman Villa," originally designed for A. M. Eastwick of Philadelphia and published as Design X in Sloan's Model Architect.

By the 1870s, architecture had emerged as a recognized profession in the United States; however, many of the nation's first well-known architects had to study abroad, since little to no formal training was available in America. Because of the scarcity of formally trained architects, it was common for local builder-architects, many of whom learned their craft in related enterprises such as carpentry, to copy designs and floor plans from published architectural pattern books. While one source reported that Jedediah Wilcox borrowed the architectural plans for the house from his brother Dennis Wilcox (1828–1886), who had an "imposing" home on nearby Colony Street, it is likely that Augustus Truesdell was inspired by designs featured in Samuel Sloan's well-circulated publications Model Architect (1852) and Sloan's Homestead Architecture (1861). Architectural historian Brian Cofrancesco, who has conducted extensive research into the Wilcox house, identified that its floor plan and exterior had many similar elements, including the massing of the facade and the small octagonal tower at the rear, to the plans and elevations for "A Norman Villa," originally designed for A. M. Eastwick of Philadelphia and published as Design X in Sloan's Model Architect.

Image: Floor plan for Design X, "A Norman Villa," in Samuel Sloan's Model Architect (1852, v. 1). Truesdell's floor plan for the Wilcox mansion varies from Sloan's plan. It was common for local architects to modify and customize published architectural designs

Interior of the House

Left: Floorplan of the first floor of the Wilcox mansion. American Wing curatorial files. Right: Detail of the fireplace mantel

Visitors entered the Wilcox house through the vestibule into the imposing main hall, with its magnificent mahogany and black walnut staircase. Off of the hall was a small reception room, parlor, sitting room, dining room, library, and conservatory, as well as a butler's pantry and water closet, a very modern convenience. The second floor held the family's bedchambers, including a luxurious suite consisting of a bedroom, dressing room, and water closet for Jedediah Wilcox, along with an additional bedchambers, a sitting room, and a drawing room positioned in the nook of the front tower. The attic, located in the mansard roof, contained rooms for unmarried domestic employees, a billiard room, a storeroom, and the water tank, which used rain water from the roof and could hold up to three thousand gallons of water. The basement featured the wine vault, a furnace and coal room, a vegetable storeroom, large kitchen, and laundry facilities.

The Wilcox house is an unusual example of a nineteenth-century American home in which exterior and interior design may have been overseen by a single architect. It was more common in the period after the Civil War for an architect to design the exterior, while a separate cabinetmaking and decorating firm would outfit the interior. An article in the Meriden Daily Republican reported that architect Augustus Truesdell "designed and superintended" the entire building. Whether Truesdell was completely responsible for the interiors is not known, but the design of many aspects of the interiors are complementary to the style and detailing of the exterior. Samuel Sloan's books often included drawings of appropriate interior doors and woodwork for his house designs, and sometimes he even included decorative paint schemes for ceilings. It is possible that Truesdell, following Sloan's model, designed the rooms' walls and decorative woodwork and helped select objects like the mantelpieces.

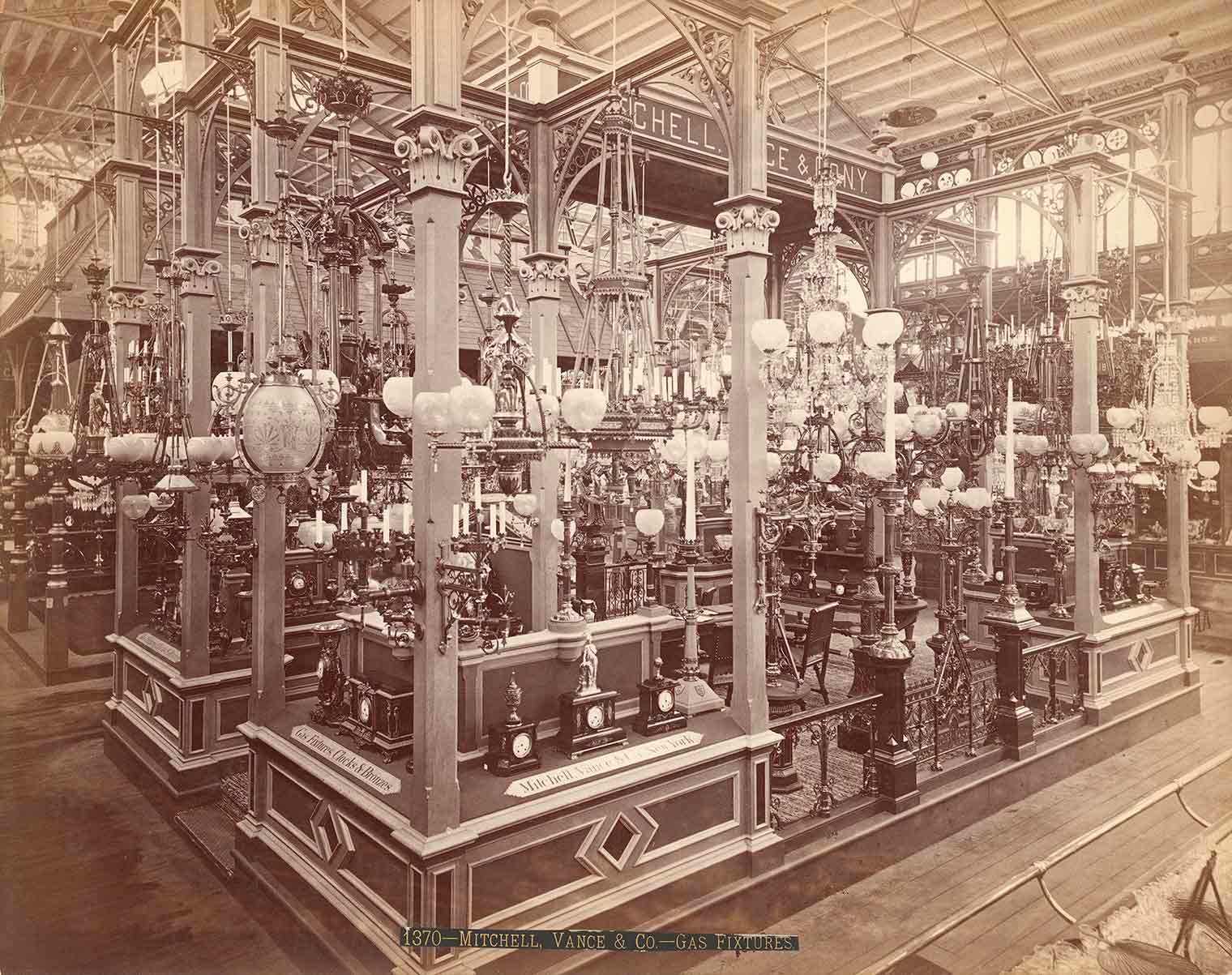

The same newspaper article noted that Hubble and Co. of Bridgeport, Connecticut "executed the upholstery work, and it reflects the highest skill upon their judgement and ability." This work likely covered not just the upholstery of the furniture in the forty rooms, but the extensive layers of window drapery that was fashionable at this time. Somewhat puzzling, the account goes on to say that "The furniture was all manufactured specially for the Wilcox mansion by Mitchell, Vance and Co. of New York." Mitchell, Vance and Co. was a renowned manufacturer of gas lighting and other decorative metalwork such as clocks and bronzes. While they were undoubtedly responsible for the light fixtures throughout the house, which were designed to coordinate with the decorative features of the other interior elements, it is highly unlikely that the firm had anything to do with the house's chairs, sofas, tables, beds, and other furnishings. Further research into the furniture, which was designed in the same coordinated Renaissance Revival style throughout the rooms of the house, has resulted in it being attributed to the Newark, New Jersey cabinetmaking firm John Jelliff and Co.

The sitting room

Left: View of the Renaissance Revival Room. Right: Doorway in the Renaissance Revival Room

The sitting room, or rear parlor, now installed at The Met, features a large bay window set off by a columnar screen featuring two fluted Corinthian columns. The door frames and paneled dado are painted white and harmonize with the snow-white Italian marble mantel. The decorative program of the room's woodwork utilizes Classical acanthus leaves, anthemion pendants, floral bosses, and scrolls—motifs that are echoed in the room's rosewood furnishings, all attributed to John Jelliff and Co. The Jelliff suite is enhanced with incised and gilded decoration, and includes mother-of-pearl medallions on the crests of the furniture, overmantel mirror, and window cornices, which are carved with elegant ladies' heads in profile. Both the formal parlor and the sitting room were considered predominantly women's domains. In the nineteenth century, it was usual that after entertaining guests at dinner, gentlemen would remain in the dining room to converse, while the ladies withdrew to the parlor. The sitting room, in turn, was usually a private retreat for the family, where activities such as reading, playing music, sewing, and private conversation might take place. The room's soft wall color, the white woodwork, and the decoration of the ceiling add to its feminine quality.

In its original location, the sitting room was behind the principal parlor, set at a right angle to it. The two rooms opened onto each other through a large archway outfitted with heavy sliding pocket doors, made of white oak, with mahogany and walnut panels. The decoration of parlor and adjacent sitting room was quite similar, though the parlor, described in one newspaper as being "upholstered in the Grand Duchesse style," was slightly larger and some of its architectural elements, like the mantel, were slightly more ornate. The same source described the sitting room as being, "fitted up in the Marie Antoinette style of art, the crimson curtains, sofas, lounges, chairs and furniture generally being covered with scarlet satin."

In its original location, the sitting room was behind the principal parlor, set at a right angle to it. The two rooms opened onto each other through a large archway outfitted with heavy sliding pocket doors, made of white oak, with mahogany and walnut panels. The decoration of parlor and adjacent sitting room was quite similar, though the parlor, described in one newspaper as being "upholstered in the Grand Duchesse style," was slightly larger and some of its architectural elements, like the mantel, were slightly more ornate. The same source described the sitting room as being, "fitted up in the Marie Antoinette style of art, the crimson curtains, sofas, lounges, chairs and furniture generally being covered with scarlet satin."

Image: Detail of the overmantel mirror in the Renaissance Revival Room

Jedediah Wilcox (1827–1897)

Left: Portrait of Jedediah Wilcox. Charles Henry Stanley Davis's History of Wallingford, Conn., from its Settlement in 1670 to the Present Time (1870). Right: J. Wilcox and Company factory, Meriden, Connecticut, as rebuilt after the 1865 fire. Charles Henry Stanley Davis's History of Wallingford, Conn., from its Settlement in 1670 to the Present Time (1870)

Jedediah Wilcox made and lost a fortune during his lifetime. Born in Middletown, Connecticut, born to Elisha B. (1795-1881) and Hepzibah Wilcox (d. 1877), the sixth of their twelve children, he arrived in nearby Meriden in 1845 and began organizing the first of his many businesses, which included J. Wilcox and Company, Colt and Wilcox Carpet Bag Factory, Meriden Tape Company, Wilcox Britannia Company, also known as the Wilcox Silver Plate Company, and the Meriden Fire Insurance Company. While he ran unsuccessfully for mayor of Meriden, he was a city alderman, President of the Meriden Horse Association, and served on the board of several local companies. Wilcox's business success allowed him to spend lavishly, and at the peak of his career he was described as the "Croesus of Meriden."

Wilcox married Clarissa Hovey (1822–1892) in 1848, and the couple had one son, Erving, who died at the age of four in 1863. He and Clarissa divorced shortly after their son's death and he soon remarried to Henrietta Blinn Deming (1842/1843–1907). They had one daughter, Lillian, born in 1867. In November of 1870, the Wilcox family moved into their newly built and furnished Broad Street house.

A series of misfortunes befell Wilcox in the years around the time he completed his new home. His woolen mills suffered devastating fires twice—once in 1865 and again in spring 1870. Four years after the second fire, Wilcox was forced to sell the house at auction for only $20,000 due to bankruptcy. The family moved to New Haven, where city directories record that he served as treasurer and board member of the Waters Patent Heater Co., the American Gas Savings Company, and the Hawthorn Spring Company. Changing homes frequently, Wilcox never seemed to recover his fortune. An avid horseman, he died in 1897 at the Galt House, a hotel in Louisville, Kentucky, a city renowned for its equestrian associations. Census reports record that his wife and daughter continued to live in New Haven until Henrietta's death in 1907.

J. Wilcox and Company: Hoop skirts, corsets, balmorals, and shawls

Left: Wilcox began his career in Meriden producing carpet bags similar to this example. Carpetbag, ca. 1860. American. Wool, leather, metal, cotton. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Mae Schenck, 1963 (2009.300.3832a, b). Right: The full profile of the skirts of dresses worn in the mid- to late-nineteenth century was achieved with the use of lightweight hoop skirts, or "cage crinolines." This example, with hoops of steel held together with linen tape, was made at about the time the Wilcox was building his mansion, and probably looks much like the products he produced. Cage crinoline, 1868–70. American. Linen, metal. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Louise M. Coleman, 1949 (2009.300.6603)

Jedediah Wilcox began his Meriden business ventures in 1848 by manufacturing carpet bags, a type of inexpensive luggage made from remnants of carpet trimmed with leather. After adding partners and capital in 1853, he established the firm of J. Wilcox and Company, and started to produce ladies' belts as well. The business boomed in the 1850s, and in 1858 he put hoopskirts and corsets into production. In 1860 he built a separate mill "filled with woolen machinery for the manufacture of Balmoral skirts" as well as "an extensive dye house". At the peak of the company's reputation, they employed about five hundred people, including women and youths, and operated their machinery until nine o'clock in the evening to accommodate the demand for their products.

In 1865, the factory burned, reportedly destroying $250,000 worth of property. Luckily, Wilcox was well-insured, and immediately built a new larger mill across the street, which produced an even wider variety of woolen goods, including "various styles of ladies cloakings, shawls, flannels, balmoral skirts, cassimeres, etc." Balmorals skirts were a type of warm woolen petticoat, often red with black stripes at the bottom, that were meant to be seen when an active lady hitched up her overskirt while engaging in outdoor activities. They could be made already attached to hoop skirts (another Wilcox product) and were named after the attire that Queen Victoria wore when she took long country walks around her Scottish estate, Balmoral Castle.

In 1865, the factory burned, reportedly destroying $250,000 worth of property. Luckily, Wilcox was well-insured, and immediately built a new larger mill across the street, which produced an even wider variety of woolen goods, including "various styles of ladies cloakings, shawls, flannels, balmoral skirts, cassimeres, etc." Balmorals skirts were a type of warm woolen petticoat, often red with black stripes at the bottom, that were meant to be seen when an active lady hitched up her overskirt while engaging in outdoor activities. They could be made already attached to hoop skirts (another Wilcox product) and were named after the attire that Queen Victoria wore when she took long country walks around her Scottish estate, Balmoral Castle.

Image: Detail of "Skating in Central Park, New York," showing two women wearing Balmoral skirts. After Winslow Homer (American, 1836–1910). Skating in Central Park, New York, 1861. Color lithograph with hand coloring, image: 16 3/4 x 27 in. (42.4 x 68.7 cm), sheet: 19 1/4 x 29 1/2 in. (48.9 x 74.8 cm). The Edward W. C. Arnold Collection of New York Prints, Maps and Pictures, Bequest of Edward W. C. Arnold, 1954 (54.90.605)

Augustus Truesdell (1810–1872)

An etching depicting the William B. Spencer house in West Warwick, Rhode Island, designed by Augustus Truesdell, built 1869–70. From Oliver Payson Fuller's History of Warwick, Rhode Island (1875)

Like many nineteenth-century American architects, Augustus Truesdell began his career as a carpenter. As he perfected and expanded his trade, he identified himself as a builder-architect and after the Wilcox house commission, he listed his profession as "architect" in the 1870 U.S. Census. The Meriden Daily Republican described the Wilcox mansion as "an enduring monument" to Truesdell's "great professional ability."

While Truesdell is best known for the Wilcox house, he was involved in several regional commissions, including ecclesiastical buildings and other private residences. About the same time as the Wilcox commission, Truesdell built a less ornate Italianate house for William B. Spencer in West Warwick, Rhode Island. Two years after he completed the Wilcox and Spencer houses, Truesdell died at the age of sixty-two in the house that he built for himself at the beginning of his career in Rockville, Connecticut.

John Jelliff (1813–1893)

John Jelliff was the founder of New Jersey's best-known nineteenth-century cabinetmaking firm, John Jelliff and Co. Jelliff began his career working with Thomas L. Vantilburg from 1836 until 1843, when he established his own firm at 301–303 Broad Street in Newark. Described as of "good character," and "industrious," Jelliff gained prominence designing and overseeing the production of furniture in the Rococo Revival, Néo-Grec, Elizabethan, and Renaissance Revival styles. He reduced his participation in the firm in 1860, and the credit-checking company R. G. Dun recorded that Jelliff retired around 1867, when he moved to a large Italianate villa just outside of Newark. John Jelliff and Co. continued to flourish under the direction of Henry Miller until 1890 when Miller changed the firm's name to Henry H. Miller. In 1893, Jelliff's obituary in the New York Times heralded him as "a pioneer of the furniture manufacturing industry in Newark."

Charles Parker (1809–1902) and later owners of the house

Left: Portrait of Charles Parker, from Charles Henry Stanley Davis's History of Wallingford, Conn., from its Settlement in 1670 to the Present Time (1870). Right: Charles Parker Company (1832–1957). Chair, ca. 1880–90. Brass, silver and other plates, 34.25 x 17 x 14 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Promised Gift of Barrie A. and Deedee Wigmore (L.2019.66.42)

Following Jedediah Wilcox's bankruptcy in 1874, his house and furnishings were auctioned off. Newspapers initially reported that the house and the majority of its furnishings were purchased by William L. Bradley of Boston, but days later it was noted that Bradley "passed" ownership to Charles Parker, Meriden's first mayor and another leading local industrialist. Parker founded the Charles Parker Company, which manufactured a variety of brass goods, including firearms, hardware, and artistic brass furnishings.

After Parker's death, his son Dexter (1849–1925) resided in the mansion with his sister Anna Lyon and her family. Following Dexter's death in 1925, his widowed brother-in-law William Lyon and his daughter and son-in-law Elsie and William Hinsdale, the last of three generations of the Parker family, lived in the house until 1934. It was then purchased by Josephine Fiala and the house became a retirement community called Beechwood Lodge.

Valets, maids, and cooks

A massive residence like the Wilcox-Parker mansion required a robust household staff to maintain it. Shortly before occupying the house in 1870, Jedediah Wilcox placed an ad seeking "An American Housekeeper, a thorough and competent person to take charge of a first-class house." Wilcox's specification for an "American" housekeeper points toward a xenophobic attitude concerning the hiring of domestic help, since at the time, these positions were largely filled by immigrant Irish women and men.

According to the 1880 U. S. Federal Census, the house's second owner, Charles Parker, who had suffered some sort of paralysis shortly after acquiring the property, employed Edwin Pulley (1849–1936), a twenty-nine-year-old African American man, as his manservant. Pulley resided at the mansion along with Annie Hawthorne and Hannah McQuilen, who were employed as a chambermaid and cook, respectively. Pulley only appears as part of the Parker household on the 1880 census but remained in the family's employ for almost fifty years. He worked as Parker's valet until his employer's death in 1902 and then as a caretaker of the property until his own death in 1936. He married Ella Porter (1858–1916) in 1883 and moved off the Parker property. Pulley and Parker may have had a close relationship, suggested by the large sum of money Parker bequeathed to Pulley at his death.

Edwin Pulley was not the only long-tenured employee at the Parker household. By 1900, the family employed three women, Sarah Slattery, Norah Doohan, and Annie Doohan, who each remained in their positions as chambermaids and cooks for almost twenty years. Irish-born sisters Nora and Annie Doohan found employment at the Parker residence within a few years of immigrating. By 1918, Annie had sought employment elsewhere, but Norah remained employed as a cook until 1924. Sarah Slattery, born in New York to Irish immigrants, also worked and lived at the Parker residence during the same period.

Demolition

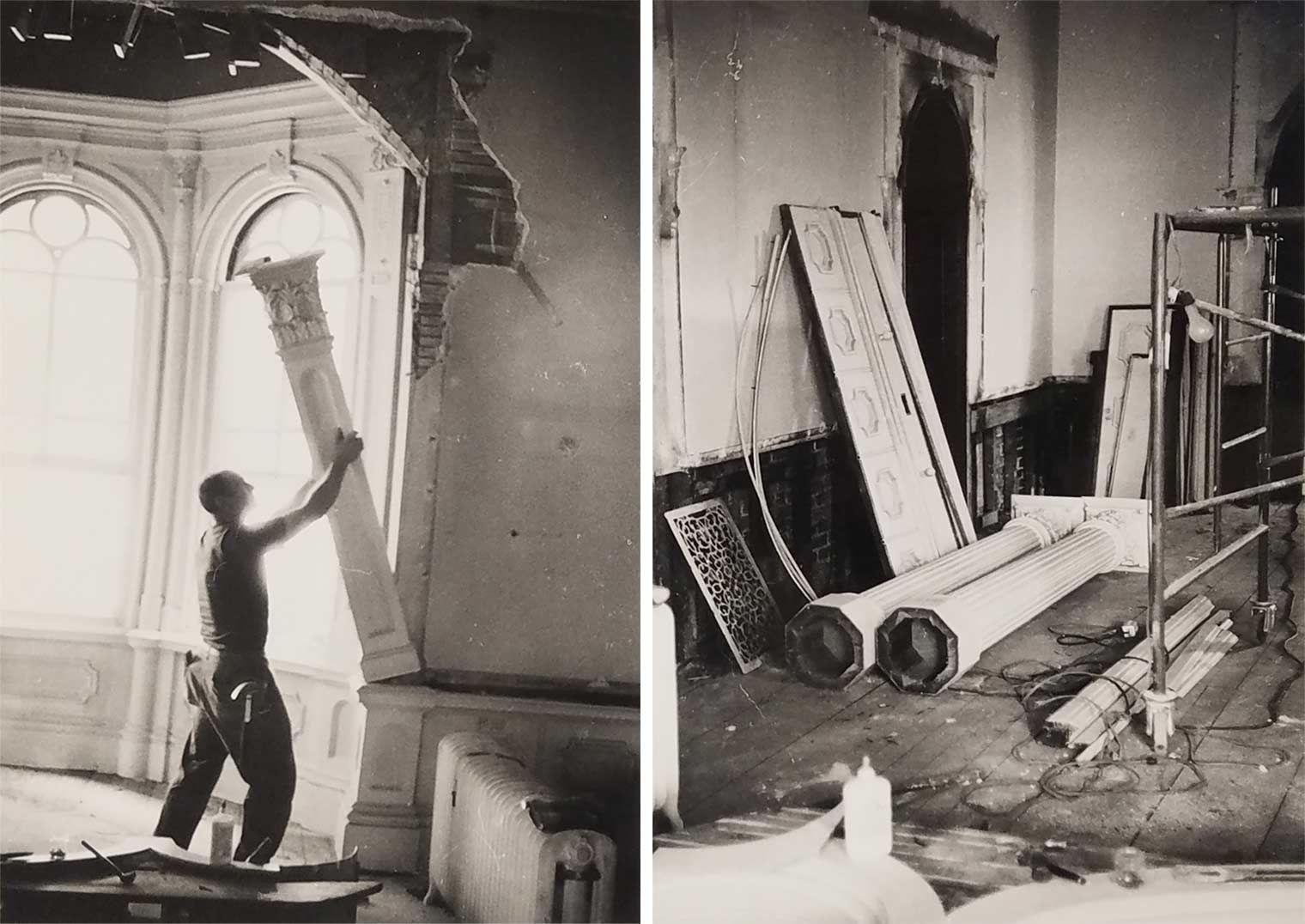

Architectural elements being removed from the Wilcox-Parker mansion, then Beechwood Lodge, ca. 1968. American Wing curatorial files

In 1968, the Mobil Oil Company purchased the property with the intention of developing a gas station and a seventy-five-unit motel on the site. The citizens of Meriden, led by their mayor, attempted to rescue the mansion with the vision of turning it into a museum. Historic preservation was still in its infancy, and the group was unable to raise enough money to buy the house and grounds from Mobil. The house was torn down, but the gas station and motel were never constructed. Portions of the Wilcox-Parker estate have since been redeveloped for commercial and residential purposes.

Before the house was demolished, curators at The Met arranged to purchase the architectural elements of the front hall and staircase, front parlor, and rear parlor, along with its overmantel mirror, window cornices, and suite of seating furniture. The elements of the front parlor were sold to Yale University, and those from the hall and staircase were sold at public auction. The Museum kept the architecture and furnishings from the rear parlor and installed them as a period room in 1985.

Installing the Renaissance Revival Room

After storing the architectural elements from the sitting room for many years, the Museum installed them as a period room in 1985. The painted ceiling, attributed to Meriden craftsman Bela Carter, was recreated for the installation and features a molded central medallion, trompe l'oeil panels, and at each end of the room, a design of two interlaced squares surrounding bouquets of delicate pink and white roses. Drawing on period descriptions of the room and examples of other American parlors from the 1870s, museum curators supplemented original objects with decorative arts and paintings appropriate in function, style, and date.

After storing the architectural elements from the sitting room for many years, the Museum installed them as a period room in 1985. The painted ceiling, attributed to Meriden craftsman Bela Carter, was recreated for the installation and features a molded central medallion, trompe l'oeil panels, and at each end of the room, a design of two interlaced squares surrounding bouquets of delicate pink and white roses. Drawing on period descriptions of the room and examples of other American parlors from the 1870s, museum curators supplemented original objects with decorative arts and paintings appropriate in function, style, and date.

Image: Detail of the recreated ceiling in the room

Reproducing upholstery, textiles, draperies, and carpet

Eastman Johnson (American, 1824–1906). The Hatch Family, 1870–71. Oil on canvas, 48 x 73 3/8 in. (121.9 x 186.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Frederic H. Hatch, 1926 (26.97)

When The Met acquired the room's elements and furniture suite, none of the original textiles had survived. A 1870s article in the Meriden Daily Republican described the room as having sofas, lounges, chairs, and furniture "covered in scarlet satin." Following this description and other period documents, such as Eastman Johnson's The Hatch Family, which depicts a room of the same period, a modern red satin upholstery fabric with a corresponding tape trim was used to re-cover the seating furniture. The tufted backs and seat are accented with cloth-covered buttons.

To reproduce the window treatments, curators examined illustrations in late nineteenth-century design books and studied paintings and photographs of American interiors furnished during the same period. Drawing on these examples, the reproduced designs have inner sheer embroidered white curtains, called "glass curtains" in the era, since they kept outsiders from looking through the glass windows. The abundant floor-length satin outer draperies are topped with cloth valances bordered by applied decorative tape, as well as fringe, and drop tassels. The valances are affixed to rosewood cornices that were designed en suite with the other furniture in the room.

To reproduce the window treatments, curators examined illustrations in late nineteenth-century design books and studied paintings and photographs of American interiors furnished during the same period. Drawing on these examples, the reproduced designs have inner sheer embroidered white curtains, called "glass curtains" in the era, since they kept outsiders from looking through the glass windows. The abundant floor-length satin outer draperies are topped with cloth valances bordered by applied decorative tape, as well as fringe, and drop tassels. The valances are affixed to rosewood cornices that were designed en suite with the other furniture in the room.

The wall-to-wall carpet and its border were reproduced from fragments in the collection of the Old Merchant's House Museum in New York City. The Tredwells, the original owners of the Old Merchant's House bought the Wilton weave (looped pile) carpet in Paris in 1867.

Image: Reproduced window treatments in the Renaissance Revival Room. Attributed to John Jelliff and Co. (1843–90). Window cornice, ca. 1870. Rosewood, gilt, and mother-of-pearl. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, American Wing Restricted Building Fund, 1968 (68.143.8)

The Renaissance Revival style

Left: Jean-Baptiste-Bernard Demay (French, 1759–1849). Armchair (Bergère à la reine) (one of a pair), ca. 1785. Carved and gilded walnut, modern silk lampas, 40 3/8 × 27 × 24 1/8 in. (102.6 × 68.6 × 61.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman Gift, 1973 (1973.305.3). Right: Attributed to John Jelliff and Co. (1843–90). Armchair, 1868–70. Rosewood, ash, mother-of-pearl, 44 1/2 x 28 1/2 x 29 3/8 in. (113 x 72.4 x 74.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Josephine M. Fiala, 1968 (68.133.3)

Mid-to-late-nineteenth-century American furniture and interior design are characterized by a constantly evolving march and mingling of different styles based on European models. From the 1850s through the 1870s, a renewed interest in the architectural and decorative vocabularies of the Renaissance brought about a revival of certain aspects of this earlier style in European and American architecture and decorative arts. Designers and cabinetmakers incorporated modern aesthetic philosophies and new technologies to create bold reinterpretations in what is today called the Renaissance Revival style. Nineteenth-century designs combined classical architectural elements, such as columns, pediments, and caryatids with a rich vocabulary of Renaissance motifs, including scrolling foliage, strap-work, and mythical grotesque creatures.

Renaissance Revival style furniture is eclectic and can take its inspiration from objects dating anywhere from the sixteenth century (see 88.10.3) to the eighteenth century. During its years in fashion, the Renaissance Revival style in the United States embraced two design paths: a heavier ornately carved style (see 1993.168 and 1995.150.1) and a lighter style, today called Néo-Grec, distinguished by eighteenth-century French and Neoclassical motifs. Néo-Grec furniture relied on intricate surface design (see 68.100.1 and 1994.441) and took its basic inspiration from eighteenth-century French forms. The Wilcox furniture suite by John Jelliff and Co. is closer to the Néo-Grec style, with the overall composition of the armchair deriving from French bergères dating to the reign of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, almost exactly one hundred years earlier, though the elements of strapwork in the crests clearly refer to Renaissance motifs.

Attributed to John Jelliff and Co. (1843–90). Sofa, 1868–70. Rosewood, ash, pine, mother-of-pearl, 45 7/8 x 76 3/4 x 31 in. (116.5 x 194.9 x 78.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Josephine M. Fiala, 1968 (68.133.1)

Walnut, rosewood, and mahogany were often used as primary woods in the most expensive furnishings, and luxurious details such as complex veneers of different colored woods in intricate patterns, gilt-bronze mounts, gilded incised line decoration, and inset medallions of carved mother-of-pearl or hand-painted porcelain, added to their opulence. In this same era, advances in upholstery technology, such as the invention of metal coil spring inner supports, allowed for firm yet highly comfortable seating, which often employed the rich look of deeply tufted seats and backs.

Suite of seating furniture

Attributed to John Jelliff and Co. (1843–90). Sofa, 1868–70. Rosewood, ash, pine, mother-of-pearl, 45 7/8 x 76 3/4 x 31 in. (116.5 x 194.9 x 78.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Josephine M. Fiala, 1968 (68.133.1)

A newspaper article published shortly after the house was completed described the furniture as being "all manufactured specially for the Wilcox mansion." The original suite of seating furniture from the sitting room consists of a sofa, a pair of armchairs, and a pair of side chairs. The suite was likely completed by a matching center table and another pair of side chairs, but these were no longer in the Wilcox house at the time the Museum acquired the room. While it is not marked by a cabinetmaker or accompanied by a surviving bill of sale, the furniture has been attributed to John Jelliff and Co. This attribution is based on its similarity to a documented Jelliff armchair in the collection of the Newark Museum of Art, which exhibits identical decorative motifs, including the relief carved mother-of-pearl medallion inset on the chair's crest rail. The Newark Museum's armchair descended in the family of Edwin Van Antwerp of Newark, New Jersey, along with its original invoice from Jelliff's firm.

Image: Attributed to John Jelliff (American, 1813–1893). Side chair, 1868–70. Rosewood, ash, mother-of-pearl, 38 1/2 x 22 x 26 3/4 in. (97.8 x 55.9 x 67.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Josephine M. Fiala, 1968 (68.133.4)

Cabinet

Dating from about 1870, and not original to the room, this grandly architectural Néo-Grec-style Renaissance Revival cabinet is constructed of rosewood with light-wood inlays. Although its origin is unknown, the sophistication of its design points to the likelihood that it was made by a New York City cabinetmaker. Cabinets like this were meant for storage as well as to display precious artistic objects, and this one is crowned by a pair of contemporaneous porcelain vases (see 68.69.15 and 68.69.16) with pâte-sur-pâte decoration designed by Marc-Louis Emanuel Solon and manufactured at the Minton factory, Stoke-on-Trent, England.

Dating from about 1870, and not original to the room, this grandly architectural Néo-Grec-style Renaissance Revival cabinet is constructed of rosewood with light-wood inlays. Although its origin is unknown, the sophistication of its design points to the likelihood that it was made by a New York City cabinetmaker. Cabinets like this were meant for storage as well as to display precious artistic objects, and this one is crowned by a pair of contemporaneous porcelain vases (see 68.69.15 and 68.69.16) with pâte-sur-pâte decoration designed by Marc-Louis Emanuel Solon and manufactured at the Minton factory, Stoke-on-Trent, England.

Image: Cabinet. American, ca. 1870. Rosewood, 81 x 66 1/4 x 20 in. (205.7 x 168.3 x 50.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1964 (64.236)

Center table

The walnut center table on view in the Renaissance Revival Room, also attributed to John Jelliff and Co., is original to the Wilcox-Parker mansion but likely furnished the principal parlor, not the sitting room. The oval-shaped tabletop's elaborate marquetry design featuring flowers, grains, and gardening tools, including a shovel, sickle, and rake. A porcelain plaque surrounded by a gilt-bronze mount decorates the table's apron on each long side, while marquetry panels with musical trophies ornament the narrow ends.

Easel and portfolio stand

Artworks such as prints and drawings were often displayed in parlors or sitting rooms to entertain and impress guests. Decorative easels, such as this walnut example with mounted portfolio, provided a fashionable way to safely store and exhibit these collected works on paper. The lower portion of the easel contains the portfolio, which has a fall-front that opens for the upright storage of art. The top of portfolio cabinet provides a wide ledge to support artworks displayed above, against the incline of the easel. The conventionalized carved floral motifs, accented with various inlaid and ebonized details, reflect the slightly later Modern Gothic style and suggest the hand of a Philadelphia cabinetmaker.

Image: Easel and portfolio stand. Made in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1880. Walnut, ebonized wood, marquetry of lighter woods, brass, 68 1/2 x 31 1/8 x 27 in. (174 x 79.1 x 68.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Martha J. Fleischman, in honor of the 75th anniversary of The American Wing, 1999 (1999.368.1a, b)

Lighting fixtures

The twelve-light brass chandelier and four two-branch sconces on view are original to the sitting room. Previously outfitted for gas lighting, the fixtures have been electrified for use in the Museum. Likely made by Mitchell, Vance and Co., the fixtures incorporate a Néo-Grec decorative vocabulary that features stylized palmettes, fleur-de-lis, and portrait medallions above the gas keys, and coordinate with the room's original suite of seating furniture, overmantel mirror, and window cornices. The etched and cut glass shades are original to the fixtures.

The twelve-light brass chandelier and four two-branch sconces on view are original to the sitting room. Previously outfitted for gas lighting, the fixtures have been electrified for use in the Museum. Likely made by Mitchell, Vance and Co., the fixtures incorporate a Néo-Grec decorative vocabulary that features stylized palmettes, fleur-de-lis, and portrait medallions above the gas keys, and coordinate with the room's original suite of seating furniture, overmantel mirror, and window cornices. The etched and cut glass shades are original to the fixtures.

Images: Top: Attributed to Mitchell, Vance and Co. Chandelier, ca. 1870. Brass, H. 68 in. (172.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, American Wing Restricted Building Fund, 1968 (68.143.5). Bottom: One of four wall sconces. Attributed to Mitchell, Vance and Co. Sconce, ca. 1870. Metal. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, American Wing Restricted Building Fund, 1968 (68.143.6)

Mitchell, Vance and Co. was incorporated in Connecticut in 1854. The company found quick success and had a retail outlet on Broadway in New York City by 1856. The firm's Connecticut origins may have led Wilcox or Truesdell to commission the firm, instead of one of their competitors, to provide the gas lighting fixtures for the entire residence. Shortly after the Wilcox commission, Mitchell, Vance and Co. won high awards at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia.

Centennial Photographic Co. Mitchell, Vance and Co. Gas Fixtures, Main Building, 1876. Albumen print. Photographic Series II, United States Centennial Exhibition Collection, Courtesy of the Free Library of Philadelphia, Print and Picture Collection

Mantel clock and obelisks

Tiffany and Co. (1837–present). Clock, ca. 1885. Marble, bronze, 18 1/8 x 20 1/8 x 7 3/4 in. (46 x 51.1 x 19.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Edgar J. Kaufmann Foundation Gift, 1968 (68.97.4)

While this Tiffany and Co. ormolu and marble mantel set postdates Wilcox's ownership of the Meriden mansion, it represents the growing interest in non-Western fine and decorative arts that began to flourish in the United States during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, following the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. The set, consisting of a clock and a pair of decorative obelisks, represents a popular rather than an archaeological idea of Egyptian art, with the hieroglyphs on the obelisks set in a meaningless arrangement.

Chauncey Bradley Ives, Rebecca at the Well

A period description of the Wilcox family's sitting room noted the presence of an Italian marble sculpture identified as "First Love," depicting a nude female figure holding a young boy. A sculpture made in Italy by American artist Chauncey Bradley Ives was selected for the Museum's installation.

A period description of the Wilcox family's sitting room noted the presence of an Italian marble sculpture identified as "First Love," depicting a nude female figure holding a young boy. A sculpture made in Italy by American artist Chauncey Bradley Ives was selected for the Museum's installation.

Ives, a Connecticut native, modeled "Rebecca at the Well" in his Rome studio in 1854. Like other American expatriate sculptors who worked in a Neoclassical style, he derived many subjects from the Bible, especially the Old Testament. In Genesis 24:11–23, Rebecca was chosen to be the bride of Isaac, the son of Abraham, after offering him water she had drawn from a well. In Ives's youthful figure of Rebecca, he was capitalizing on the renown he had achieved with sentimental images of children. The sculpture would prove to be his most successful work with twenty-five marble replicas sold over a period of forty years. Studio records indicate that half were sold to New York-area clients, who constituted a ready patronage base, both through their Grand Tour travels to Italy and Ives's savvy exhibiting and marketing of his work in the United States.

Image: Chauncey Bradley Ives (American, 1810–1894). Rebecca at the Well, 1854; carved 1866. Marble, 50 x 16 1/2 x 16 1/2 in. (127 x 41.9 x 41.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Anna C. McCreery, 1899 (99.8)

Samuel Colman, The Hill of the Alhambra, Granada

Samuel Colman (American, 1832–1920). The Hill of the Alhambra, Granada, 1865. Oil on canvas, 47 1/2 x 72 1/2 in. (120.7 x 184.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Oswald C. Hering, in memory of her husband, 1968 (68.19)

During his first trip to Europe in 1860–61, Samuel Colman was captivated by southern Spain and began a series of paintings. His interest in the region and its Moorish architecture, unusual for an American painter during this period, was further fueled by contemporary literature, particularly Washington Irving's The Alhambra (1832). Colman situated his image of the picturesque architecture in the past by including figures in Renaissance dress, inspired by Irving's description of courtly processions held during the reign of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella in the late fifthteenth century. Colman's work goes beyond illustration, however, with his brilliant command of color, atmospheric clarity, and convincing perspective.

American Revival Styles, 1840–76

Nineteenth-century American architecture and furniture design was characterized by a parade of different styles that purported to take their inspiration from the design vocabulary of the past.