McKim, Mead and White Stair Hall

Buffalo, New York, 1882–84

Cynthia V. A. Schaffner, Research Associate

This gracious Stair Hall, installed in Gallery 741, once stood in the home of Erzelia Stetson Metcalfe (1832–1913) at 125 North Street in Buffalo, New York. In July 1882, Mrs. Metcalfe commissioned the newly formed New York City architectural firm of McKim, Mead and White to design the house for herself and her son James. The room features a fashionable "inglenook"—a fireplace flanked by built-in benches—and a dramatic staircase with a half-story landing lit by leaded-glass windows. The oak paneling incorporates a rich collage of forms and textures. Here, the Metcalfe family greeted their visitors.

The Stair Hall

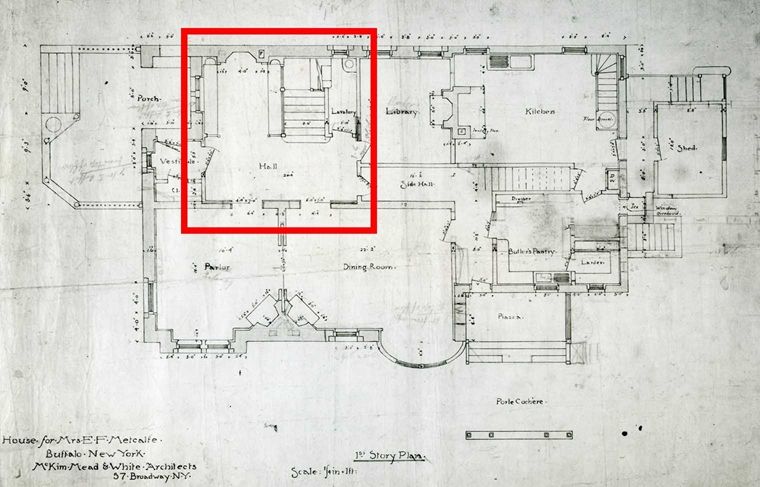

Ground-floor plan of the Metcalfe House by McKim, Mead and White, 1882. The Stair Hall (in red) drew guests into the heart of the home and served "as a spacious yet cozy and informal lounging-place," according to Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer, an architecture critic and friend of the Metcalfes'. Courtesy of The Buffalo History Museum

Inspired by the multipurpose ground-floor halls of early American colonial houses, where families ate, slept, and performed the tasks of daily life, the stair halls—also known as living halls—of the 1870s and 1880s were designed as large and welcoming spaces. As seen in the ground-floor plan, the main entrance to the Metcalfe House was through a wide, colonial-style split door (also known as a Dutch door) into a small paneled vestibule. The vestibule led to the expansive Stair Hall, where sliding doors opened onto the parlor, dining room, and library.

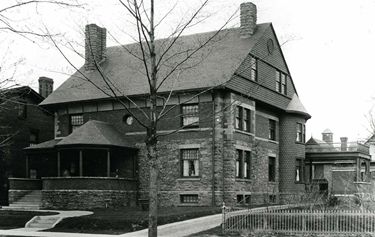

The exterior

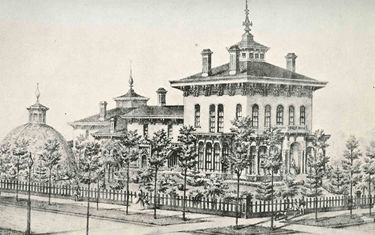

The two-and-a-half-story Metcalfe House was clad in rough-hewn red Medina sandstone on the first story, red brick on the second story, and terracotta tiles on the massive gable-end roof. Built by local craftsmen, it was the first of four Buffalo houses designed by McKim, Mead and White. In 1886, the Buffalo Real Estate Builder's Monthly called the Metcalfe House "an example in domestic architecture unique . . . in this part of the state." The house received national attention when it was featured in George William Sheldon's influential book Artistic Country-Seats (1886).

Image: The Metcalfe House, Buffalo, New York, as pictured in George William Sheldon's Artistic Country-Seats: Types of Recent American Villa and Cottage Architecture with Instances of Country Club Houses, published in 1886

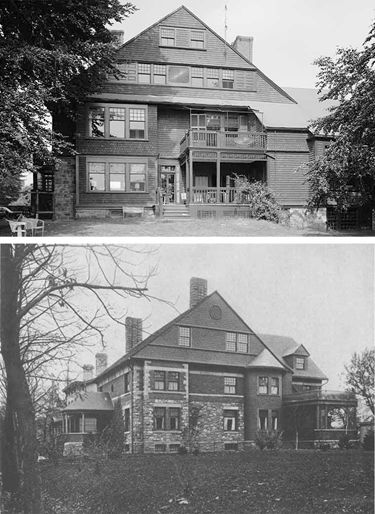

Early shingle style

Although the Metcalfe House was not sheathed in wood shingles, it is regarded as an early example of McKim, Mead and White's Shingle Style. Like the shingle-clad Samuel Tilton House in Newport, Rhode Island, the Metcalfe House exhibits a synthesis of English Queen Anne elements and seventeenth- and eighteenth-century New England farmhouse features. The richly textured exteriors, the bell-roof turrets, and banks of multipaned windows of both the Metcalfe and Tilton Houses allude to elements adapted from the English style. The houses' gable-on-podium shape and turned spindle railings reference colonial American elements.

Images: The Tilton House (top) and the Metcalfe House (bottom) are examples of McKim, Mead and White's Shingle Style. While the seaside Tilton House is sheathed in shingles, the Metcalfe House is clad in sandstone, brick, and tiles, materials more fitting for its suburban setting. Photograph of the Tilton House, Library of Congress. Photograph of the Metcalfe House from George William Sheldon, Artistic Country-Seats (1886)

Colonial Revival movement

The Centennial International Exposition, held in Philadelphia in 1876, stimulated widespread interest in the United States' colonial heritage and promoted the Colonial Revival. This cultural phenomenon inspired a reworking of elements from the architectural styles and interior designs of early American homes. During the 1880s, McKim, Mead and White forged their own Colonial Revival manner by freely interpreting, in what they called the "modern colonial" style, details taken from measured drawings of early New England houses. The result was an original American architecture that came to be known as the Shingle Style.

Image: In 1874 Charles McKim hired a local photographer to take pictures of eighteenth-century buildings in Newport, Rhode Island. He showed the photographs to prospective clients who wanted houses built in the "modern colonial" style. Photograph of Whitehall, the Bishop Berkeley House, Newport, Rhode Island. Collection of the Newport Historical Society

The interior

Inside the Metcalfe House, fireplaces with raised paneling above the mantels formed the focal points of nearly every room. Here, the simplicity of the smooth marble contrasts with the elaborately carved overmantel and the strapwork panel above the mirror. Beamed and paneled ceilings were purposely low to evoke an old-fashioned style and to conserve heat during cold Buffalo winters. Sunlight through the multipaned leaded-glass windows illuminated the rooms during the day, and the soft glow of gas sconces lit the finely ornamented interiors in the evening.

Image: The fireplace in the Metcalfe Stair Hall is faced with unpolished yellow Siena marble that, with its coral veining, accentuates the terracotta interior of the fireplace

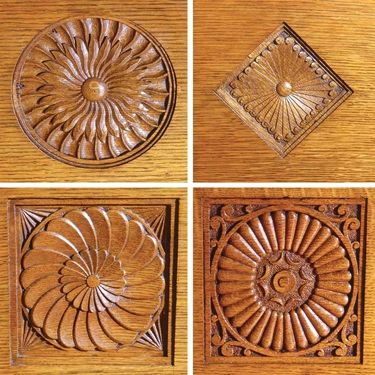

The Stair Hall paneling

The oak- and cherry-paneled woodwork and decorative surfaces of the Stair Hall reflect McKim, Mead and White's genius for intermingling disparate decorative sources. While intricately carved Renaissance ornament predominates in the overall scheme, the walls of the broad staircase feature Japanesque latticework on one side and Islamic openwork spindles on the other. The fireplace, of oak and Siena marble, has a carved overmantel flanked by pilasters and tall shell-carved niches—elements derived from colonial American architecture. These types of eclectic details are expressions of Stanford White's decorative virtuosity and are characteristic of the firm's early Shingle Style suburban residences.

Image: Carved ornaments decorating the frieze in the Metcalfe Stair Hall include a sunflower (upper left), an emblem of the Aesthetic movement

Stained glass windows

McKim, Mead and White designed the intricately conceived leaded-glass windows specifically for the Metcalfe House. They were made in New York City by the Decorative Stained Glass Company, a firm formed by two of artist John La Farge's top glassmakers after La Farge's decorating business failed in the early 1880s. According to McKim, Mead and White's bill books, the windows are the only architectural elements of the Metcalfe House that were not fabricated in Buffalo.

Image: Color leaded glass windows in the Metcalfe Stair Hall

The architects: McKim, Mead, and White

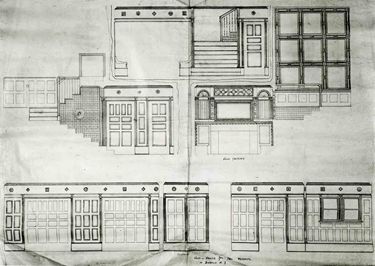

McKim, Mead and White was the leading architectural firm of late-nineteenth-century America. The plans for the Metcalfe House attest to the firm's skillful integration of decorative ornament and essential architectural components. While the ground floor followed Charles McKim's concept of a classic Stair Hall with broad doorways leading to the main rooms, the surviving paneling and woodwork reveal Stanford White's expertise in elaborate surface decoration and exemplify the firm's use of built-in furniture and glistening decorative finishes. The renowned artistic integrity of McKim, Mead, and White was a result of the three partners' nuanced collaboration.

Image: The Metcalfe Stair Hall elevations record the restrained exuberance and exacting attention to detail that characterize the designs of McKim, Mead and White. Elevations of the Metcalfe House Stair Hall by McKim, Mead and White, 1882. Courtesy of The Buffalo History Museum

The Metcalfe family

Erzelia Stetson Metcalfe's husband, James Harvey Metcalfe (1822–1879), arrived in Buffalo from Bath, New York, in 1855. After succeeding as a livestock dealer in the port city at the terminus of the Erie Canal, he later established Buffalo's First National Bank and organized the Buffalo, New York and Philadelphia Railroad. James Metcalfe also served as a Buffalo Parks Commissioner and helped implement Frederick Law Olmsted's plan for the city's park system. The Metcalfes had five children: Frances Ester (1851–1933), James Stetson (1858–1927), George S. (1859–1934), Francis Tyler (1865–1921), and Guy Thomas (1868–1879).

Image: The Metcalfe children grew up in this Italianate villa on the corner of North and Summer Streets in Buffalo. The domed-shaped building in the garden was a glass conservatory. Lithograph, Frank H. Severance, ed., The Picture Book of Earlier Buffalo. Buffalo, N.Y.: Buffalo Historical Society, 1912.

Erzelia Metcalfe commissions McKim, Mead, and White

Three years after James Metcalfe's death in 1879, his wife, Erzelia, commissioned McKim, Mead and White to build a house for herself and her eldest son, James Stetson Metcalfe. The Metcalfes' daughter, Frances Metcalfe Bass Wolcott, likely encouraged her mother to commission the newly formed New York City firm to design the house, as she knew the architects socially. Throughout her adult life, Frances Wolcott was active in the New York City art world. Her friends included sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, artist John La Farge, and architecture critic Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer.

Image: Photograph of Frances Metcalfe Bass Wolcott from her autobiography, Heritage of Years: Kaleidoscopic Memories (1932). Wolcott remembers ". . . the life my mother presided over—a brilliant center—first in the old house, which was sold at my father's death, and then in the first house in Buffalo planned and erected by McKim, Mead & White. . . ."

McKim, Mead and White Architectural Firm

(1879–1961)

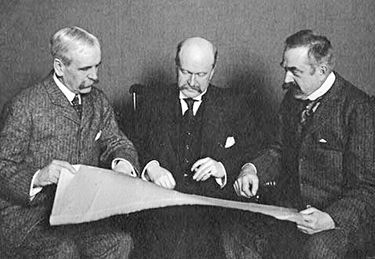

Charles Follen McKim (1847–1909), William Rutherford Mead (1846–1928), and Stanford White (1853–1906) formed their architectural partnership in 1879. Mead undertook the management of the firm, while McKim and White were the executive designers. The Metcalfe House marks the start of the firm's most creative period (1879–1915) and is representative of its innovative early Shingle Style commissions. Along with Frank Lloyd Wright, McKim, Mead and White are among the most eminent figures in American architectural history.

Image: From left to right: William Rutherford Mead, Charles Follen McKim, and Stanford White in a photograph from ca. 1905.

Efforts to preserve the Metcalfe House

The Metcalfe House as it appeared in the 1970s. Hare Photographs.

In 1905 Erzelia Metcalfe sold the McKim, Mead, and White house to Edwin Thomas, who made several alterations. From 1921 it served as a boarding house and by the late 1970s it was slated for demolition by the Delaware North Companies, which were establishing headquarters next door and needed the land for a corporate parking lot. Despite neglect, the superb woodwork of the principal interiors of the Metcalfe House survived in excellent condition, and local preservationists mounted a campaign to save the house.

Demolition of the Metcalfe House

Despite preservation efforts, in December 1979, the Delaware North Companies were granted permission to demolish the Metcalfe House, yet it was stipulated that portions of the building's interiors be saved. As a result, the Delaware North Companies donated the Stair Hall to The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Buffalo State College received the dining room, and the Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society received the library and architectural fragments.

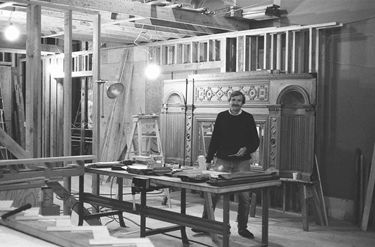

Image: The Stair Hall in the Metcalfe House in 1980, just before it was dismantled and brought to the Museum. Hare Photographs.

Installing the Metcalfe Stair Hall

Between 1990 and 1992, the Metcalfe Stair Hall was installed in the Museum's American Wing. A team of curators, conservators, restoration carpenters, and architects participated in the installation. The room's quarter-sawn white oak paneling was meticulously reassembled and restored to its lustrous finish. The arms on the benches, missing when the room was acquired, were replaced based on original drawings. Museum visitors now enter the Metcalfe Stair Hall through a former doorway and exit through an opening into the vestibule, where the original colonial-style split, or Dutch, door is situated.

Image: The installation of the Metcalfe Stair Hall in the American Wing.

Furnishing the Metcalfe Stair Hall

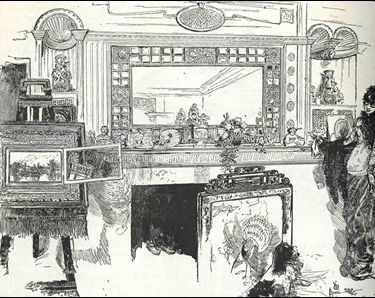

The cohesive design of the Metcalfe Stair Hall, with its built-in benches, leaded-glass windows, and superlative woodwork, requires few furnishings. Lacking documentation of how Erzelia Metcalfe furnished the Stair Hall, Museum curators have added objects popular in artistic houses of the late nineteenth century. The illustration on the right of the fireplace in another contemporaneous McKim, Mead, and White house may reflect the way Metcalfe decorated her inglenook.

Image: "Parlor Fire-Place in House of H. Victor Newcomb, Esq., Sunny Sands, Elberon, N.J.," The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine (June 1886)

Card stand

Brass, once associated with basic utilitarian objects, became popular during the Aesthetic movement as a material used in the production of stylish furniture and other objects such as lighting fixtures, mirror frames, and decorative hardware. This small table incorporates ceramic elements that were likely made in Europe but were considered Japanese in style. Used for holding calling cards or displaying small decorative objects, the delicate stand reveals Victorian interest in melding modern technology with exotic foreign designs.

Image: Bradley & Hubbard Manufacturing Company, Card stand. Meriden, Connecticut, ca. 1880–1885. Brass, earthenware. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Dr. Alain and Ellen Roizen, 2008 (2008.572.1)

Vase

Mary Louise McLaughlin, founder of the Cincinnati Pottery Club in 1879, produced and decorated this monumental vase for the Club's first exhibition in May 1880. Decorated with calla lilies on a deep blue ground with a gold crackle glaze, it is among the largest pieces of art pottery ever produced in the United States.

Image: Mary Louise McLaughlin (1847–1939), Vase. Cincinnati, Ohio, 1880. Painted and glazed earthenware. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Anonymous Loan (L.1987.11)

Portrait plaque of M. B. Brown

Rosina Emmet is best known for her oil portraits. This early work represents her interest in painting on ceramics, a decorative art form practiced by many women during the late nineteenth century. Emmet's portrait plaques may have been inspired by English examples she encountered while visiting London in 1876.

Image: Rosina Emmet (1854–1948), Portrait plaque of M. B. Brown. Plaque manufactured by Josiah Wedgwood and Sons, ca. 1878–85. Earthenware, polychrome enamel. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Sansbury-Mills Fund, 1991 (1991.25)

Landscape plaque

Decorated by John Mackie Falconer (1820–1903), manufactured by James Carr's Pottery. Landscape plaque. New York, New York, 1878. Earthenware, polychrome enamel with gilding. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Emma and Jay Lewis, 1997 (1997.57)

The winter scene on this plaque was executed by the Scottish-born Brooklyn painter John Mackie Falconer. Inspired by the Aesthetic movement's corollary household arts movement, many academically trained painters applied their talents to ceramic decoration in late-nineteenth-century America. The inscription on the back of the plaque records that the one-story house illustrated was built in 1788 and was considered "The Oldest House in St. Louis." The manufacturer’s mark is the great seal of the United States flanked by the initials J. C.

Covered vase

The Greenpoint neighborhood in Brooklyn was home to the Faience Manufacturing Company, established in 1881 to produce ornamental ceramic wares such as vases, umbrella stands, and jardinieres. In 1884 china decorator Edward Lycett (1833–1910) joined the firm as artistic director. Under his leadership, his team of talented potters and china painters produced objects that displayed a synthesis of Asian and Middle Eastern decoration, as seen in this vase.

Image: Faience Manufacturing Company. Covered vase. Brooklyn, New York, 1881–1892. Earthenware, polychrome enamels and raised gold paste decoration. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Florence I. Balasny-Barnes, in memory of her parents, Elizabeth C. and Joseph Balasny, 1981 (1981.432.4)

Ewer

Typical of the art pottery movement of the 1880s, this ewer reveals the influence of ceramic styles from many international sources. The pinched spout derives from an Islamic ceramic form, the depictions of birds and insects are characteristic of Japanese decoration, and the enamel decoration outlined in gold relief was fashionable in English Royal Worcester porcelain.

Image: Faience Manufacturing Company, Ewer. Brooklyn, New York, 1886–90. Earthenware, polychrome enamels and raised gold paste decoration. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Friends of the American Wing Fund, 1984 (1984.424)

Andirons and fire tools

Left: Andirons. England or Europe, ca. 1800. Brass. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1922 (22.120.1, .2); Right: Fire shovel and fire tongs. England, ca. 1800. Brass, steel. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Flora E. Whiting, 1971 (1971.180.65a; 1971.180.65b)

Left: Andirons. England or Europe, ca. 1800. Brass. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1922 (22.120.1, .2); Right: Fire shovel and fire tongs. England, ca. 1800. Brass, steel. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Flora E. Whiting, 1971 (1971.180.65a; 1971.180.65b)

The antique brass andirons, tongs, and fire shovel in the Metcalfes' fireplace reflect a symbolic interest in the United States' colonial past and a corresponding commitment to its preservation and artistic revival.

Tall clock

The movement and dial of this Chippendale-style clock were produced by Joseph Mulliken of Concord, Massachusetts. An unidentified cabinetmaker fashioned the mahogany case with its three-part design: a bonnet for the clock face, a shaft for the long pendulum, and a pedestal to support the entire unit. The placement of a tall clock at the bottom of the stairs recalls an icon of the United States' colonial past, immortalized in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's poem "The Old Clock on the Stairs" (1845). The nostalgic verse inspired the placement of colonial timepieces on the staircases of countless late-nineteenth-century American homes.

Image: Joseph Mulliken (active 1775–1800), Tall clock. Concord, Massachusetts, ca. 1790. Mahogany, white pine. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Olive B. Floyd, in memory of Alice Downing Hart Floyd and Mary Jane Murray Farnsworth, 1985. 1986.82

Kazak rug

This nineteenth-century rug, produced in the Caucasus region bordering Europe and Asia, adds pattern and color to the inglenook of the Metcalfe Stair Hall. The sage green bench cushions are made of reproduction mohair plush that harmonizes with the rug.

Image: Kazak rug. Russian, 19th century. Wool. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Fenella and Morrie Heckscher, 2008 (2008.675)

Keep Learning

Women China Decorators

Read more about women led china-decorating movement of the late nineteenth century in this Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History essay.

Edward Lycett (1833–1910)

Read more about the work of Edward Lycett and the Faience Manufacturing Company in this Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History essay.