New York Dutch Room

Bethlehem, New York, 1751

Matthew Thurlow, Research Associate

The woodwork in the New York Dutch Room, installed in Gallery 712, demonstrates the reliance on traditional Netherlandish building practices in colonial New York. Dutch immigrants began settling the Hudson River Valley in the early seventeenth century. They constructed houses and barns much as they had in the Netherlands. This main chamber, called a groote kaner in Dutch, comes from a house built in 1751 for Daniel Pieter Winne (1720–1800), whose ancestors moved to Rensselaerswyck (present-day Albany County) from Flanders via Curacao in 1643.

The room is presented as a gallery rather than furnished as a period room. It features furniture, metalwork, ceramics, and glass distinctive to New York-area households of Dutch heritage.

A view of the New York Dutch Room.

Setting

Dutch settlement of the New World originated on the island of Manhattan, then rapidly moved northward along the Hudson River to present-day Albany, where a thriving community developed through farming and trade with Native American tribes.

According to the Finnish explorer Peter Kalm, who visited Albany in 1749–50, the town's residents sent to New York City, "boards or planks, and all sorts of timber, flour, peas, and furs, which they get from the Indians, or which are smuggled from the French…. The extensive trade which [they] carry on, and their sparing manner of living, in the Dutch way, contribute to the considerable wealth which many of them have acquired."

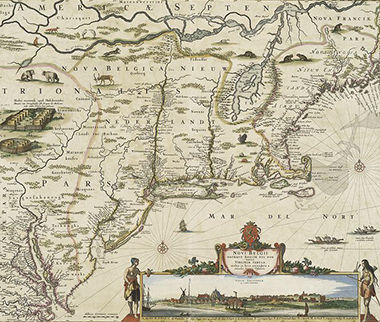

Image: Colonial America's Eastern Seaboard, as shown in Nicholaes Visscher's Atlas Contractus (1655–57). The map illustrates Dutch settlement in present-day New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut during the early 1600s. New York Public Library

Netherlandish architecture in Colonial America

Daniel Pieter Winne's house was built in 1751. Even though Winne's family had lived in the Upper Hudson River Valley for almost a century, the style of building very much resembled that practiced in the Netherlands since medieval times.

Daniel Pieter Winne's house was built in 1751. Even though Winne's family had lived in the Upper Hudson River Valley for almost a century, the style of building very much resembled that practiced in the Netherlands since medieval times.

The Winne family lived in the house for several generations. David (1819–1882) and Catherine (1827–1893) Winne were the last family members to do so. Their daughter and granddaughter continued to rent the house until it was finally sold out of the family in 1954.

Image: A conjectural rendering of the Daniel Pieter Winne House

Exterior

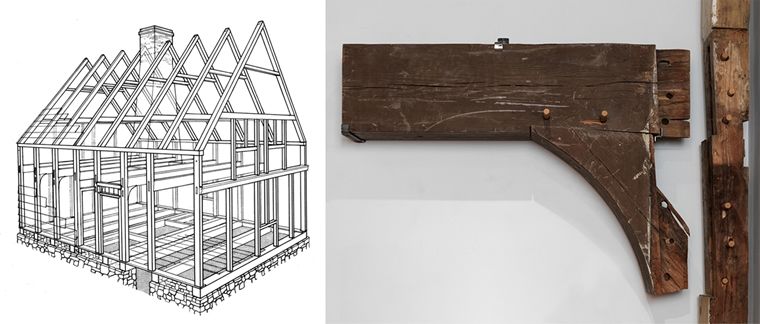

Left: Conjectural rendering of framing of the Winne House. Right: Detail of mortise-and-tenon joint and corbel from the Winne house framing

The dominant external feature of a Dutch home was its steep gable roof. Houses were constructed with a series of post-and-beam supports known as "anchor bents." The curved corbels that connected the bents were both structural and decorative. The complete assemblage of an anchor-bent, mortise-and-tenon joint and its corbel can be seen in the rendering of the Winne House framing.

The spaces between the bents were filled with locally manufactured bricks—known, when used for this purpose, as nogging—and then covered with pine clapboards. The interior face of the nogging was plastered and whitewashed. The smoothly planed posts and beams and clean white walls would have enhanced the natural light entering the room from the double casement window.

Image: Detail of nogging, partially covered with pine clapboards

Interior

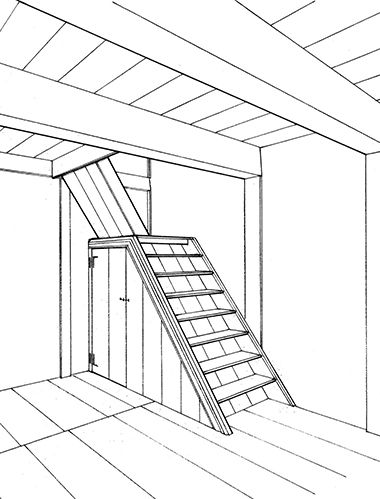

The Winne House had two rooms on the ground floor, with a half-story above and a cellar below. The Museum's room is the larger of the two first-floor chambers. The room initially had a corner staircase adjacent to the front door. There may also have been a built-in bed or cupboard in the opposite corner.

This main chamber was the setting for a wide variety of activities. As suggested by the broad, open hearth, one of its primary functions was food preparation, but it was also used for sleeping, socializing, and storing and displaying valuable household items, such as ceramics, metalwork, textiles, and clothing.

Image: Conjectural rendering of the corner staircase that provided access to the attic. A door within the stair structure led to the cellar.

Tile work

Left: Tile fragment. Utrecht, Netherlands, ca. 1750. Tin-glazed earthenware with cobalt decoration. Emily Crane Chadbourne Fund, 2003 (NYDR.2003.1). Right: A Dutch tile like the ones that would have lined the New York Dutch Room’s fireplace. It depicts the story of the wedding feast at Cana, related in the Gospel according to John (2:1–11).

When the Winne House was dismantled, carpenters discovered fragments of Dutch tiles. Earthenware tiles made in the Netherlands were common in Dutch American homes of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The tiles were applied in a vertical row between the floor and the fireplace mantel, as seen in the Museum's room. They often featured images based on New Testament passages and may have aided in the moral instruction of children in colonial New York.

Changes over time

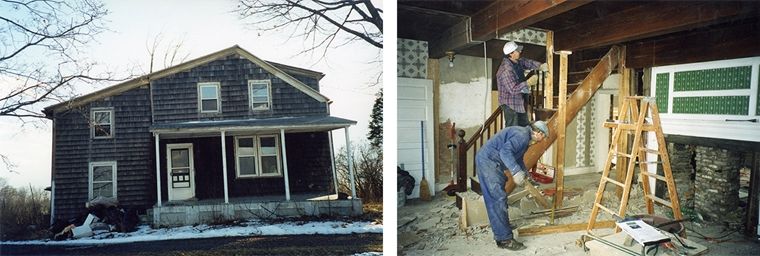

Left: The Winne House in 2002, at the time of its purchase by the Museum. J. M. Kelley, Ltd., Niskayuna, NY. Right: Carpenters removing a later staircase in the main chamber of the Winne House. The replacement chimneypiece is at right. J. M. Kelley, Ltd., Niskayuna, NY

During the nineteenth century, the Winne House underwent extensive modifications and expansions that altered and obscured the original design. The roof line changed when the Winnes added rooms to the first and attic stories along the entry side of the house in the early nineteenth century. The family expanded the house again in the 1850s or 1860s, and once more in the 1930s. All of the doors and windows were replaced several times over the years.

Inside the main chamber an English-style hearth with a small firebox replaced the open, or "jambless," fireplace. The corner staircase was removed in favor of a straight run of stairs in a narrow hall built inside the front door.

The Winne family

Pavel Petrovich Swinin (1787/88–1839). Albany, New York, 1811–13. Watercolor on off-white wove paper, 5 3/8 x 9 1/8 in. (13.7 x 23.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1942 (42.95.10)

The New York Dutch Room comes from a house built in 1751 for Daniel Pieter Winne (1720–1800), a fourth-generation resident of the upper Hudson River valley. His great-grandfather Pieter Winne (d. 1692), the progenitor of the family in America, left Ghent, in the province of Flanders (part of modern-day Belgium), and arrived in New Netherlands in 1652, after a brief stay on the Caribbean island of Curacao.

Through farming and the operation of saw and grist mills, Pieter Winne acquired a modest estate. He was able to provide his thirteen children with a comfortable upbringing. Winne's home and mill were situated on a creek named Vloman Kill (Fleming's Creek), in recognition of his Flemish origins. The Winne family continued to reside along the creek through the nineteenth century.

The Winne estate

Daniel Pieter Winne's house sat on a 141-acre property originally leased from the Van Rensselaer family by his great-grandfather Pieter. Although the estate had been divided among various family members, Daniels share of the land—valued at £10 in 1767—was sizable. We know that his uncle Adam Winne (1724–1808) inherited a mill and farm worth £30 at the same time.

In addition to farming, Daniel participated in the French and Indian War (1754–63) as an ensign in the Albany County militia and was elected as a representative to the Albany Committee of Safety during the American Revolution (1775–83).

Image: Daniel's uncle Adam Winne as a child in a portrait attributed to Pieter Vanderlyn (ca. 1687–1778), ca. 1730. Oil on canvas. Winterthur Museum

Landlords and tenants

Woodwork and wallpaper from the Great Hall of Van Rensselaer Manor House, 1765–69. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. William Bayard Van Rensselaer, in memory of her husband, 1928 (28.143)

For nearly two hundred years, the Winnes were tenants of the Van Rensselaer family. The Van Rensselaers were the great patroons, or manorial lords, of the Albany region. Their one-million-acre property was known as Rensselaerswyck. A room from the Van Rensselaers' grand manor house (built 1765–68) is located on the second floor of the American Wing in Gallery 752.

The Winnes' rent varied over time. Until 1764, they ceded ten percent of their annual produce to their patroon. After that, they were required to pay a fixed rate of ten bushels of wheat per year.

A momentous opportunity

Curators in the American Wing had for many years lamented the absence of a room from colonial Dutch New York in which they could display the Museum's superb collection of objects from that period and region. In 2002 the department received word of an eighteenth-century house in the Albany area about to be dismantled and sold.

The Museum decided to purchase the Winne House with the hope of installing one of the first-floor chambers among the early colonial rooms in the American Wing. The removal and later additions revealed a remarkably intact eighteenth-century frame.

Image: Eighteenth-century framing elements in the Winne House, as revealed during deconstruction

Documenting the site

Before the wood frame could be disassembled, restoration architects attached an identification number to every post, beam, corbel, and floorboard, and then produced meticulously measured drawings to document each element's original location.

Image: Detail of beams and posts with identification tags.

Dismantling the Winne house

Once the post-eighteenth-century additions had been removed, a crane operator moved the anchor bents away from the house. Carpenters removed the wood pins that had held the mortis-and-tenon joints together for 250 years and then lifted the massive posts and beams into a storage container.

Once the post-eighteenth-century additions had been removed, a crane operator moved the anchor bents away from the house. Carpenters removed the wood pins that had held the mortis-and-tenon joints together for 250 years and then lifted the massive posts and beams into a storage container.

Image: The deconstruction of the Winne House.

Installing the New York Dutch Room

The frame remained in storage until it was reconstructed inside the Museum in 2005. Each element was hoisted into the American Wing through a window in the adjacent Meetinghouse Gallery (Gallery 713). Minor adjustments included the loss of one-and-a-half inches of ceiling height in order to accommodate the original flooring and the elimination of six inches between the last two anchor bents in order to meet the depth requirements of the existing space.

The frame remained in storage until it was reconstructed inside the Museum in 2005. Each element was hoisted into the American Wing through a window in the adjacent Meetinghouse Gallery (Gallery 713). Minor adjustments included the loss of one-and-a-half inches of ceiling height in order to accommodate the original flooring and the elimination of six inches between the last two anchor bents in order to meet the depth requirements of the existing space.

Other features—such as the casement windows and shutters, the mantel and cornice, the front door, and the interior door that led to the adjoining chamber—were painstakingly reproduced from surviving eighteenth-century houses. With these restored elements in place, the Museum has accurately recreated the room's original appearance.

Image: Installers bring in elements of the Dutch Room through the Museum's windows

Kasts

Left: Kast. American, 1650–1700. Painted white oak, red oak, 70 x 67 x 25 in. (177.8 x 170.2 x 63.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Millia Davenport, 1988 (1988.21). Right: Kast. American, 1690–1720. Painted yellow poplar, red oak, white pine, 61 1/2 x 60 1/4 x 23 in. (156.2 x 153 x 58.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1909 (09.175)

The kast, a type of large cupboard, was an icon of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Dutch-American domesticity. Highly architectural in design, these monumental pieces of furniture were used for storing expensive textiles and were often presented as dowry, or wedding gifts. Local craftsmen made kasts in a range of sizes and quality, while wealthier Dutch New Yorkers owned elaborate examples imported from the Netherlands, which incorporated exotic woods that would have been difficult to obtain in the colonies. The two painted kasts on display in the Dutch Room were made around the New York City area. One is painted to imitate costly stone—a highly unusual effect—and the other employs a grisaille, or monochromatic gray palette, and depicts pomegranates and quinces, symbols of fertility.

Stained-glass window

This window, which is decorated with the Van Rensselaer coat of arms, was given in 1656 to the First Dutch Reformed Protestant Church of Beverwyck (present-day Albany), New York. The donor was Jan Baptist Van Rensselaer, director of the large estate known as Rensselaerswyck. After the church was demolished in 1805, the window was installed at the head of the staircase in the Van Rensselaer Manor House. The house was dismantled in the 1890s, and some of the interior elements, including the entry hall, now on view in Gallery 752, were given to the museum by family members in the 1920s.

Image: Evert Duyckinck (American, ca. 1620–1700). Stained-glass window, ca. 1656. Painted leaded glass, 22 3/8 x 15 1/2 in. (56.8 x 39.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Mrs. J. Insley Blair, 1951 (52.77.46)

Desk-on-frame

There is no doubt this desk was made in New York. It was discovered in Brooklyn and incorporated gumwood, a regional resource. Moreover, an inscription inside the lid records a business transaction involving one of the numerous Schenck families of Kings County, today Brooklyn, New York. The double-arched moldings that frame the pigeonholes of the interior can be dated stylistically to about 1700. However, no comparable piece is known. Since the turnings appear to derive from French prototypes, the desk may well have been made by a Huguenot-émigré craftsman working in New York.

There is no doubt this desk was made in New York. It was discovered in Brooklyn and incorporated gumwood, a regional resource. Moreover, an inscription inside the lid records a business transaction involving one of the numerous Schenck families of Kings County, today Brooklyn, New York. The double-arched moldings that frame the pigeonholes of the interior can be dated stylistically to about 1700. However, no comparable piece is known. Since the turnings appear to derive from French prototypes, the desk may well have been made by a Huguenot-émigré craftsman working in New York.

Image: Desk-on-frame, 1690–1720. American. Sweet gum, possibly mahogany veneer, yellow poplar, 35 1/4 x 33 3/4 x 24 in. (89.5 x 85.7 x 61 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1944 (44.47)

Spindle-back chair

This chair is ornamented with distinctive turnings produced in areas of Dutch cultural influence across New York and northern New Jersey. Its overall design is based on a chair form that was popular in the Netherlands during the second half of the seventeenth century and persisted in the American colonies throughout the eighteenth century.

Image: Spindle-back chair, 1680–1710. American. Cherry, ash, 35 5/8 x 18 1/2 x 15in. (90.5 x 47 x 38.1cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Gift of the Members of the Committee of the Bertha King Benkard Memorial Fund, and Bequest of Cecile L. Mayer, by exchange; and Fletcher Fund and Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, by exchange, 1997 (1997.68)

Silver

Left: Jesse Kip (American, baptized 1660–1722). Two-handled bowl, 1690–1710. Silver, 5 x 12 in. (12.5 x 30.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. William A. Moore, 1923 (23.80.17). Right: Tumbler, ca. 1691. American. Silver, 2 1/4 x 3 7/8 in. (5.7 x 9.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John Bayard Rodgers Verplanck, 1953 (53.100)

Religious rituals, marriages, the commemoration of a loved one, and other celebratory communal events often called for the commissioning or use of costly silver vessels. Those on view in the New York Dutch Room reflect the types of pieces used by Dutch Americans in the colonies. Some were made by domestic craftsmen, such as this tumbler, while others were imported from abroad. These highly valued objects were costly to acquire and were frequently passed down through generations of family members.

Two-handled bowls chased into six equal panels, such as this example by Jesse Kip, are a form peculiar to early New York silver. Their design represents a crossbreeding of northern European and English sources, with deeper roots in the Italian Renaissance, but their function closely followed Dutch practice of passing a communal beverage at ceremonial events.

Featured Video

Old Dutch Architecture in The New American Wing: A Dwelling Room from Albany County, New York

Keep Learning

The American Wing

Ever since its establishment in 1870 the Museum has acquired important examples of American Art. A separate "American Wing" building to display the domestic arts of the seventeenth to early nineteenth centuries opened in 1924; paintings galleries and an enclosed sculpture court were added in 1980.

Architecture, Furniture, and Silver from Colonial Dutch America

Read more about the craftsmanship of colonial Dutch America in this Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History essay.