The Temple's Cult and Decoration

Isabel Stünkel, Associate Curator, Department of Egyptian Art

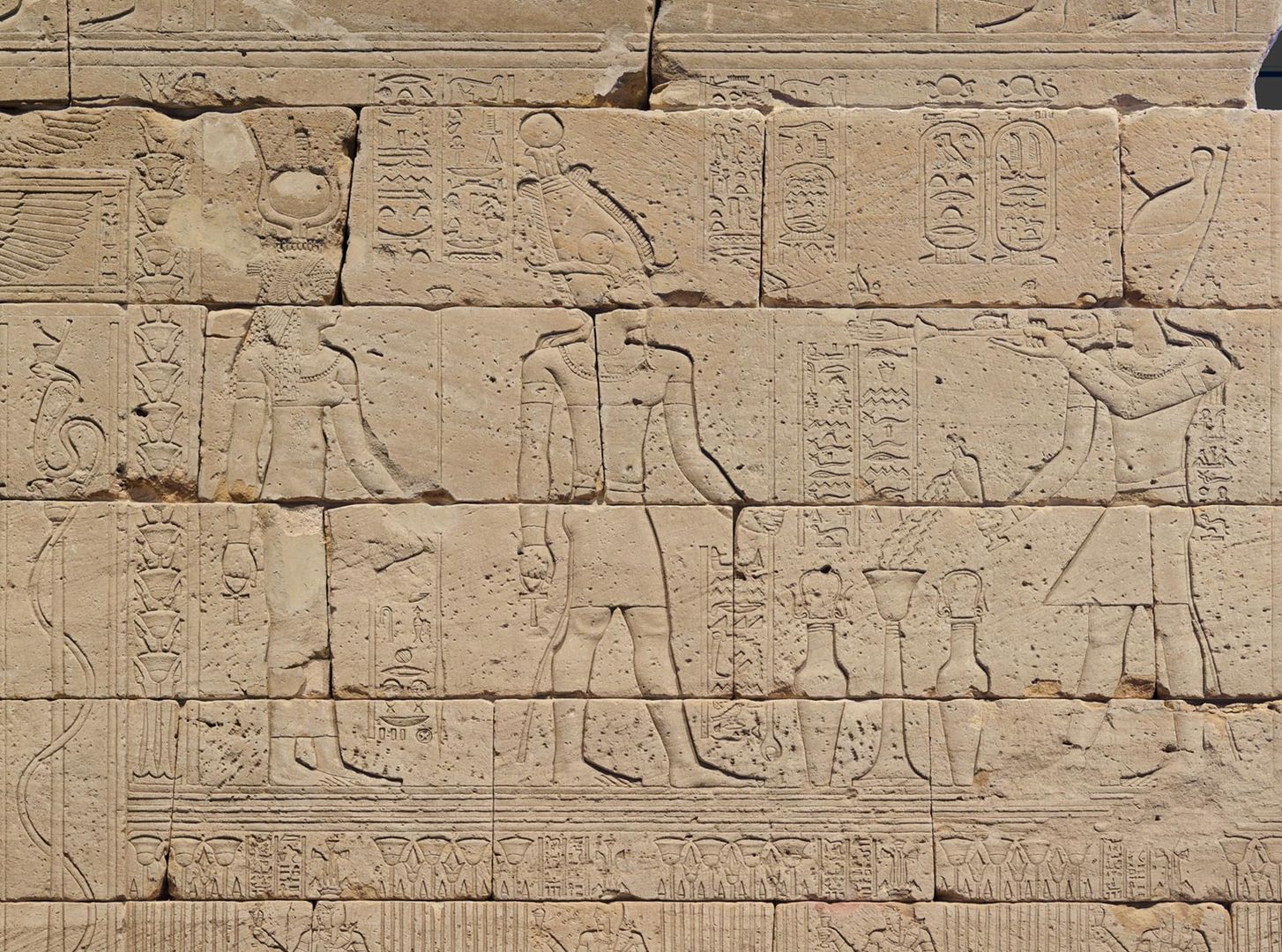

Detail of temple wall depicting Augustus (right) burning incense and pouring milk for the god Osiris (center) and the goddess Isis (left).

In ancient Egypt, temples were seen as residences for deities, who were thought to temporarily manifest themselves in the cult statues located in the sanctuary. The temples were also the stage for daily rituals that were ideally performed by the pharaoh, but in practice by priests. These cultic performances included the offering of food and beverages as well as the burning of incense, which was thought to have a purifying effect. The inner rooms of the temple were restricted to those performing the rituals. During religious festivals, cult statues could be brought out of the temple. At Dendur, they were likely carried out onto the spacious cult terrace, enabling the public to feel closer to their gods.

Detail depicting Augustus (left) offering milk to Osiris, Isis, and Harpocrates.

The Temple of Dendur was primarily dedicated to the goddess Isis of Philae, who had her principal temple on Philae, an island about fifty miles north of Dendur. Depictions of this goddess can be found in many scenes on the temple. Isis's husband, Osiris, is also featured, as is their son, Horus, who appears as both Harpocrates ("Horus the Child") and Harendotes ("Horus Who Protects His Father").

Detail depicting Augustus (left) burning incense and making a libation (a liquid offering) to the deified brothers Pedesi and Pihor (center and right).

Two other deities, Pedesi and Pihor, also played an important role. These two brothers, who may have been the sons of a local Nubian ruler, were deified after their death and are known only from the decoration of the Temple of Dendur. A small rock-cut chamber originally located in the cliff behind the temple may have been their tomb. Since Dendur stood in Nubia, to the south of the Egyptian border at Aswan, the Nubian gods Mandulis and Arsenuphis also occur among the many deities represented in the temple.

Detail depicting Augustus (left) offering the crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt to the goddess Isis (right). On top of her headdress is a small stepped hieroglyph that depicts a throne and was used to write Isis's name.

In Egypt, the Roman emperor Augustus had many temples erected that adhered to native Egyptian architectural and religious traditions, rather than to Hellenistic or Roman culture. In the decoration of these Egyptian temples, Augustus is shown in Egyptian costume, as Egyptian pharaoh, and offering to Egyptian deities. This expressed his commitment to honor the local cults and helped confirm his legitimacy as ruler of the region.

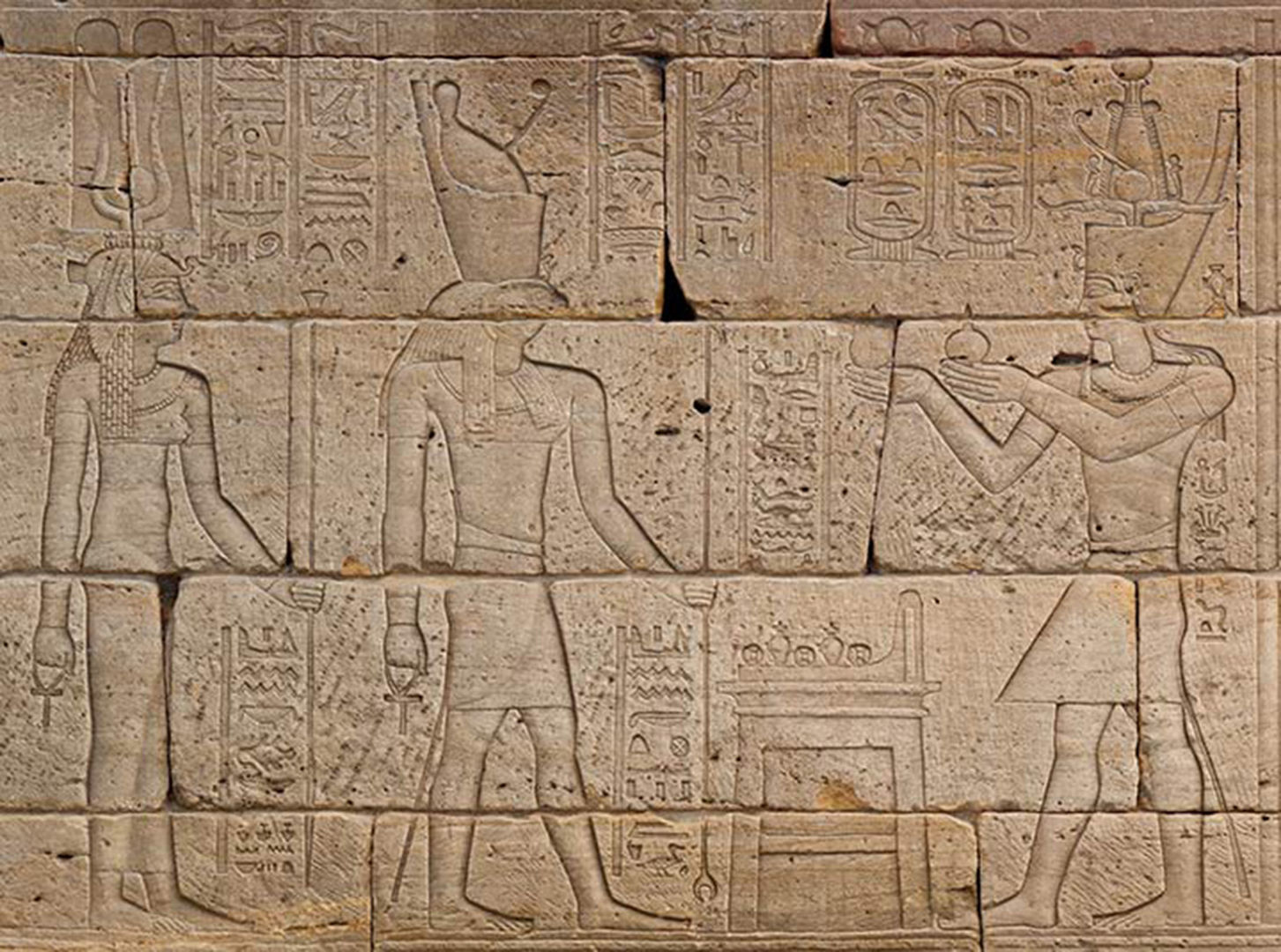

Left: Two cartouches reading "Pharaoh" in raised relief. Right: Two cartouches calling Augustus Autokrator (the Greek word for "Emperor," on the left) and Kaisaros (the Greek version of the title "Caesar," on the right), in sunk relief.

The offering scenes are accompanied by hieroglyphic inscriptions that describe the ritual actions and give the names and titles of the figures represented. Inscriptions close to Augustus feature cartouches (oval-shaped protective rings) that often read simply "pharaoh." Other cartouches call Augustus Autokrator (Greek for "emperor") or Kaisaros (Greek for the Roman title "Caesar").

Detail depicting Augustus (right) offering wine to the deities Harendotes and Hathor (center and left).

As is common in Egyptian relief decoration, the outside of the temple was carved in sunk relief, which created deep shadows in the bright sunlight. Raised relief, in which the background is carved away and the figures are raised, was used for the interior of the building. The reliefs were originally brightly painted. In nearly all of the offering scenes, the ruler stands in front of one or more deities, who may be either seated or standing, and presents them with different goods. In return, these deities were thought to have the power to offer prosperity and life, represented by the ankh (sign of life) held in their back hands.

Left: Detail depicting a shrine with a frieze of cobras at the top. In the scene below is a depiction of Pihor (right) offering to Isis (left).

In the sanctuary itself, relief carvings appear only on the rear wall. Interestingly, these are also the only scenes in the temple in which Augustus is not the person making the offering. Instead, we find the deified Pihor making an offering to Isis; below, partly destroyed, his brother Pedesi worships Osiris. The frame around and above these two scenes depicts a small shrine with a frieze of cobras at the top. Several holes drilled at the sides suggest that the offering scenes originally had two wooden doors that could be opened and closed, like those of a three-dimensional shrine.

The temple's design and decoration has several symbolic layers. In particular, many details carefully reflect its geographical orientation. For example, a cobra depicted on the south column wears the crown of Upper Egypt (south Egypt), while the cobra on the north column opposite wears the Lower Egyptian crown.

Left: Cobra with Upper Egyptian crown, representing southern Egypt, on the south column. Center: South column. Right: Cobra with Lower Egyptian crown, representing the north part of Egypt, on the north column.

According to ancient Egyptian mythological concepts, the creation of the world was thought to be renewed inside the temple, and the building itself was regarded as an image of the natural world. Thus we find carvings of papyrus and lotus plants adorning the bottom of the outside walls, with representations of the Nile god Hapy placed in between.

Capitals of the south and north columns with a winged sun disk above.

The two columns of the temple resemble tall plants that reach toward the sky, and the shape of the capitals incorporates papyrus and lily plants, the emblems of Upper and Lower Egypt. Above the columns, a large sun disk is flanked by the outspread wings of Horus, the sky god. Winged sun disks were also placed above a side entrance to the temple and above the main gate. Inside the temple, flying vultures depicted on the ceiling also evoke the sky.

In ancient Egypt, depictions were thought magically to become real. The temple's decoration thus not only guaranteed the performance of rituals, but also the continuation of the natural world and cosmic world order.