The Temple of Dendur: Architecture and Ritual

Dieter Arnold, Curator Emeritus, Department of Egyptian Art; and Adela Oppenheim, Curator, Department of Egyptian Art

View of the Temple of Dendur on the Nile. Photo by the Center of Documentation of Egyptian Antiquities, 1961–62

Architecture

The Temple of Dendur represents a modestly proportioned example of a building type, common in the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, that has its roots in earlier Egyptian architecture. The building is characterized by an entrance hall (pronaos) with columns separated by screen walls (only one is preserved), followed by two broad rooms. Approximately 43 feet long, 21 feet wide, and 16 feet high to the roof, it is constructed of local Nubian sandstone blocks, a building material regularly employed in southern Egypt and Nubia throughout pharaonic history.

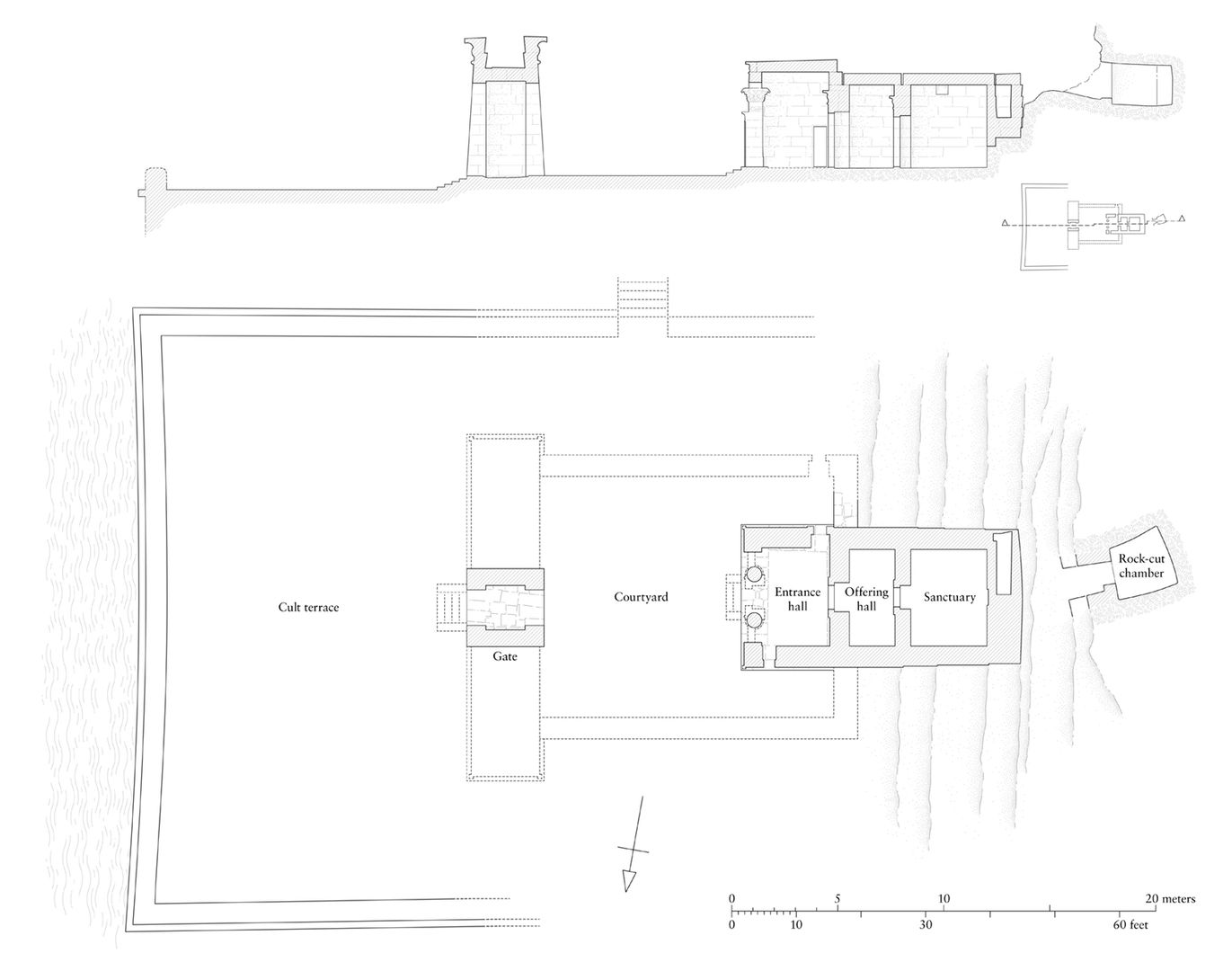

Plan and section of the Temple of Dendur. Computer rendering by Sara Chen

Originally the temple stood on a large sandstone platform above the Nile River, which has been recreated in more durable granite and further modified for display within The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The steep riverbank was not entirely leveled when the temple was built, but rather the rear walls were set into a rocky slope, also recreated in granite at The Met.

Installation view of the Temple of Dendur, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Elements that already had been used by Egyptian architects for thousands of years embellish both the temple and its gateway. These include the rounded tori at the corners and tops of the walls, and the curving cavetto cornice along the roof, both of which derive from early constructions made of reeds and other organic materials. The gateway, exterior of the temple, and entrance hall, as well as portions of the inner rooms, were decorated with elaborate scenes in raised and sunk relief. Originally painted in bright colors, they depict deities receiving offerings from the Roman Emperor Augustus, who is shown with the trappings of an Egyptian pharaoh.

Ritual

Similar to other Egyptian temples, Dendur was essentially a house in which a deity resided in perpetuity and received offerings such as food, drink, and clothing, items that were necessary for their continued existence. Egyptian religion embraced many paradoxes, including the seemingly contradictory concept that omniscient beings such as divinities required the same sustenance as human beings. A temple was not, therefore, primarily intended as a place where mortals attempted to gain divine favor through acts of worship. Rather it was a dwelling in which rituals were enacted to nurture deities who would ensure the prosperity of the community. As a consequence, ancient Egyptian temple architecture focused on accommodating the perceived requirements of the deity, rather than the needs of a large congregation of worshipers. A proper understanding of the Temple of Dendur's architectural spaces therefore must progress not from the viewpoint of a visitor approaching the structure, but instead outwards from the deity's residence in the innermost part of the building towards the terrace, where, in this case, a goddess emerged to meet her devotees.

Isis, the mistress of the southern Egyptian island of Philae, was the primary deity worshiped at Dendur. Also of great importance was the cult of Pedesi along with his brother Pihor, both of whom were probably sons of a local Egyptian ruler. The brothers were believed to have drowned in the Nile, a manner of death that could lead to a divinized state. They may have been buried in a small chamber cut into the rock cliff behind the temple, which was left in place and could not be reconstructed in the Museum.

The temple's innermost chamber, the sanctuary, contains depictions of Pedesi and Pihor, worshipping Osiris (partly destroyed) and his consort, the goddess Isis, respectively. Within the rear wall of the sanctuary is a small secret chamber accessed from outside the temple. Its purpose is uncertain, but it may have served to store cult equipment. Two openings at the top of the wall allowed light to enter the sanctuary. One or more cult statues were presumably housed in this part of the temple, likely in free-standing shrines of wood that were later destroyed. It is from this sanctuary that a cult statue of Isis would have begun its procession to the outer parts of the temple.

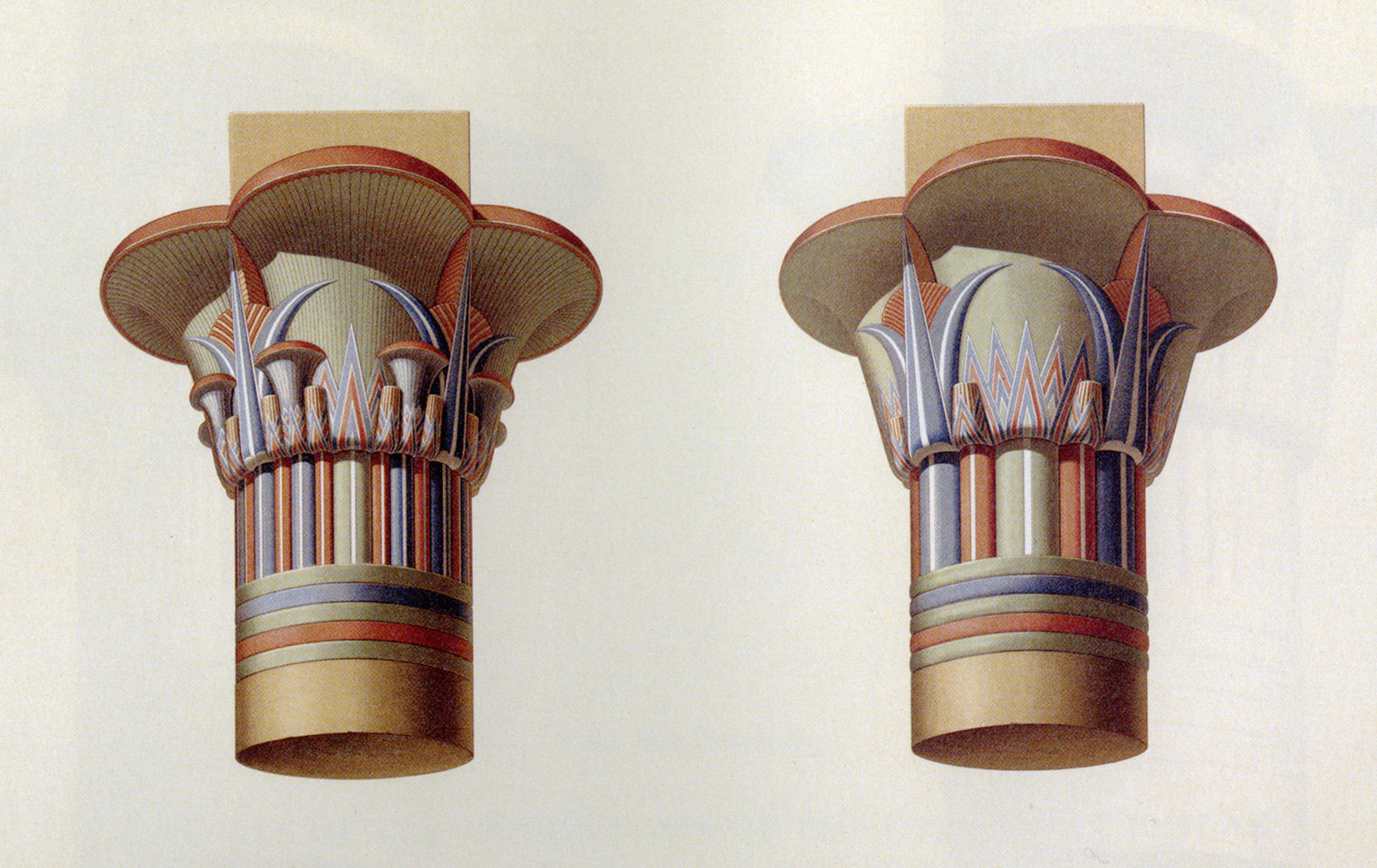

The cult image would have passed from the sanctuary to an unfinished chamber that probably served as an offering hall; only the doorframe was decorated. Continuing her progress through the temple, Isis would have passed through the entrance hall. Its roof is supported by two columns with composite capitals in the shape of papyrus and lily plants. Egyptian columns usually had vegetal forms that over time became increasingly elaborate, enlivening facades and interior space.

Composite capitals from columns in the temple of Isis on the island of Philae. Plate 58 from Emile Prisse d'Avennes, Histoire de l'art égyptien (Paris, 1878–79)

Next, the goddess would have crossed an open courtyard and exited through the massive stone gateway decorated with relief scenes on the front, back, and interior. Its sides remained rough, suggesting that the gateway was originally flanked by a pylon and/or an enclosure wall of stone or brick, all traces of which had disappeared.

View from the gateway of the Temple of Dendur, looking towards the Nile. Photo by the Center of Documentation of Egyptian Antiquities, no date

Finally, the goddess was carried onto the cult terrace, which, along with similar ones at temples such as those on Elephantine Island and at Kalabsha, seem to have been used for celebrations involving larger crowds. Although certainly still secluded within a portable shrine, Isis would here meet her worshipers along with a traveling cult image of Isis of Elephantine, another manifestation of this key Egyptian goddess.

The terrace of the temple at Kalabsha, overlooking the Nile. Photo by Dieter Arnold