Nesmin: A Man Who Lived and Died More Than 2,000 Years Ago

A detail of one of Nesmin's cartonnage elements depicting the god of mummification, Anubis. Mummy of Nesmin with plant wreath, mummy mask, and other cartonnage elements (detail). Ptolemaic Period (200–30 B.C.). From Egypt, Akhmim, Egyptian Antiquities Service/Maspero excavations 1885–86. Painted and gilded cartonnage. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Funds from various donors, 1886 (86.1.51)

«The reopening of our Ptolemaic galleries after their renovation is a good opportunity to reflect on Nesmin, whose mummy and coffin are now back on display. Modern medical technology and analysis of the inscriptions on his coffin can bring this individual, who lived more than 2,000 years ago, closer to us.»

Together with his coffin, Nesmin came to The Met more than 100 years ago and has been popular ever since. In the past, I have overheard conversations between Museum visitors who assumed that the mummy is "empty"; they thought that it was unwrapped long ago and that the textiles were put back together to look like a mummy. Luckily this is not the case. The mummy actually contains not only the body of Nesmin, but also 31 amulets that were placed between his wrappings during the mummification ritual in order to magically transfer certain powers, such as regeneration, to him. These amulets are still in place today, but are invisible to our eyes, at least without technology.

Left: The mummy of Nesmin with mummy mask and cartonnage elements

The mummy was CT scanned in 2011 with the help of the NYU Langone Medical Center's Department of Radiology. The resulting data allowed us to see these 31 amulets very clearly, and an image of them is now included in an updated label text in the new galleries. In addition, a new display of several similar amulets is presented right next to Nesmin's mummy.

People have asked if we will unwrap the mummy to take out the amulets, but we will not do so, as this would destroy the mummy and be disrespectful. With modern technology, we can explore what lies beneath a mummy's wrappings without causing any damage.

The exact location of Nesmin's tomb is not known, but the inscriptions on his coffin and the style of his cartonnage elements (decorated pieces that were placed on mummies and that are made out of linen or papyrus mixed with plaster) tell us that he lived in the third or second century B.C. in Akhmim. The town was an important religious and cultural center at that time, closely related to the fertility god Min, whom Nesmin served as a priest. Nesmin's coffin further tells us about his family: his father, Djedhor, was a priest as well, and his mother, Tadiaset, was a musician for Min.

A gallery view of Nesmin's mummy on the left and his coffin to the right

From CT scans we know that Nesmin died as a middle-aged man, so he probably had children and grandchildren by then. His teeth look good, though he did have crooked upper wisdom teeth, and there is evidence that he suffered from arthritis, which reminds us of our own ailments. The scans also show that Nesmin's body is well preserved and that his mummy not only includes his skeleton, but soft tissue that was dried during the mummification process.

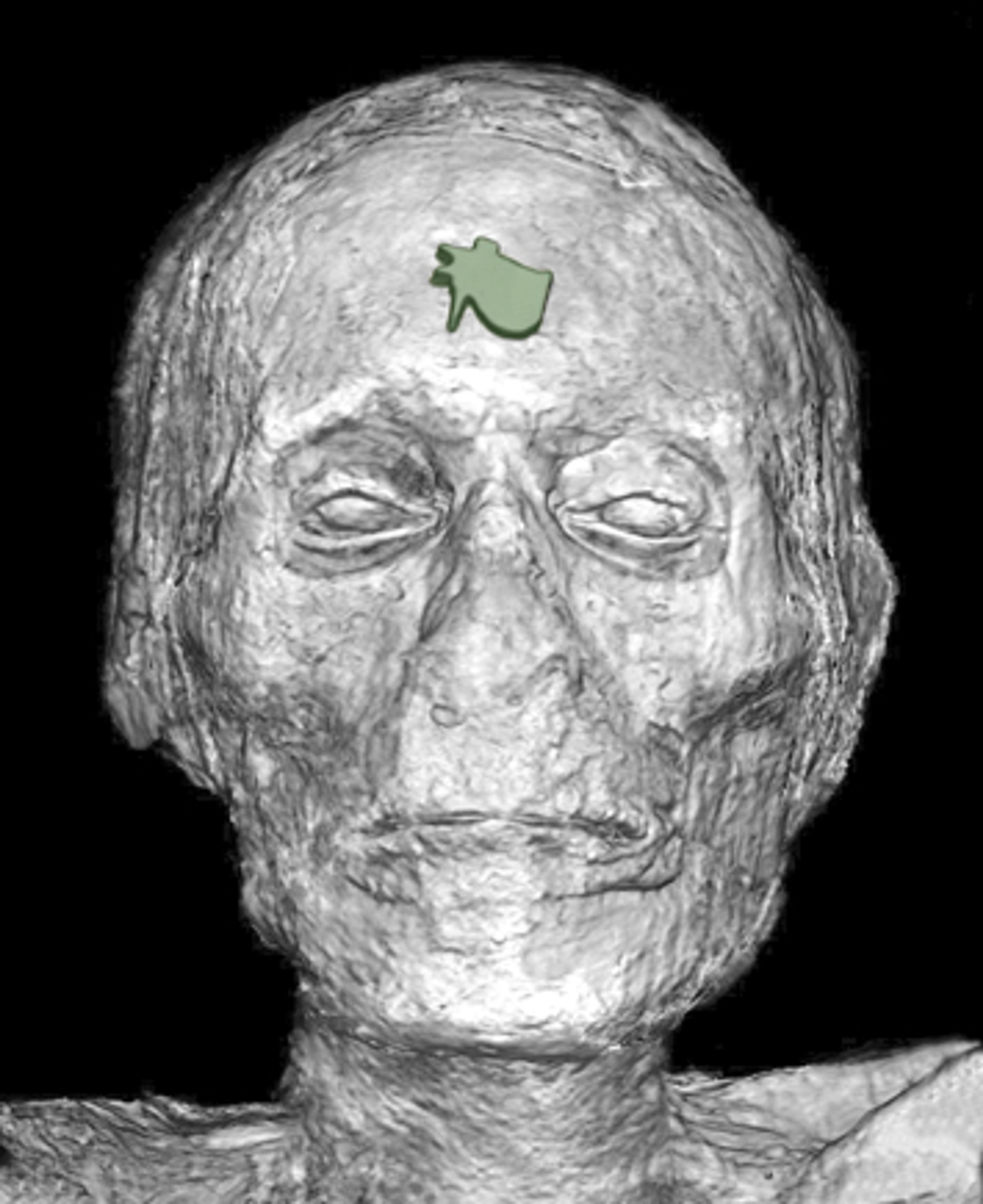

Nesmin's skull with crooked upper third molar

In the renovated gallery, an image of Nesmin's face accompanies a new wall text that discusses mummification. This image, which is called a volumetric rendering, features the head of his mummified body. The NYU radiology team used the CT scan data to produce this rendering by digitally stripping away the layers of linen. This proved to be a very difficult task, as the linen is partially soaked with resin, a dense material that was used in the mummification procedure and is often difficult to differentiate from other parts of the mummy. The result is an intriguing image of Nesmin's face that even shows that his eyes are still open!

Left: A 2016 volumetric rendering of Nesmin's head (the wedjat eye amulet on his forehead is artificially colored in green)

To me, the image of his face expresses more than anything else that this is a person. I was keen to include it in a gallery label for several reasons: On the one hand, I want our visitors to know that the mummies on display in the Museum are the wrapped bodies of ancient people who are still untouched inside the wrappings; but I also hope that the mummies are seen not just as corpses, but as the remains of people who were once alive, had a family, and were loved. To look into the face of a man who lived and died more than 2,000 years ago crosses the boundary of time and brings across the human aspect of an ancient culture.

Related Link

See all posts related to the new installation of the galleries for Egyptian Ptolemaic art.

Isabel Stünkel

Isabel Stünkel is an associate curator in the Department of Egyptian Art.