Nile and Newcomers: A Fresh Installation of Egyptian Ptolemaic Art

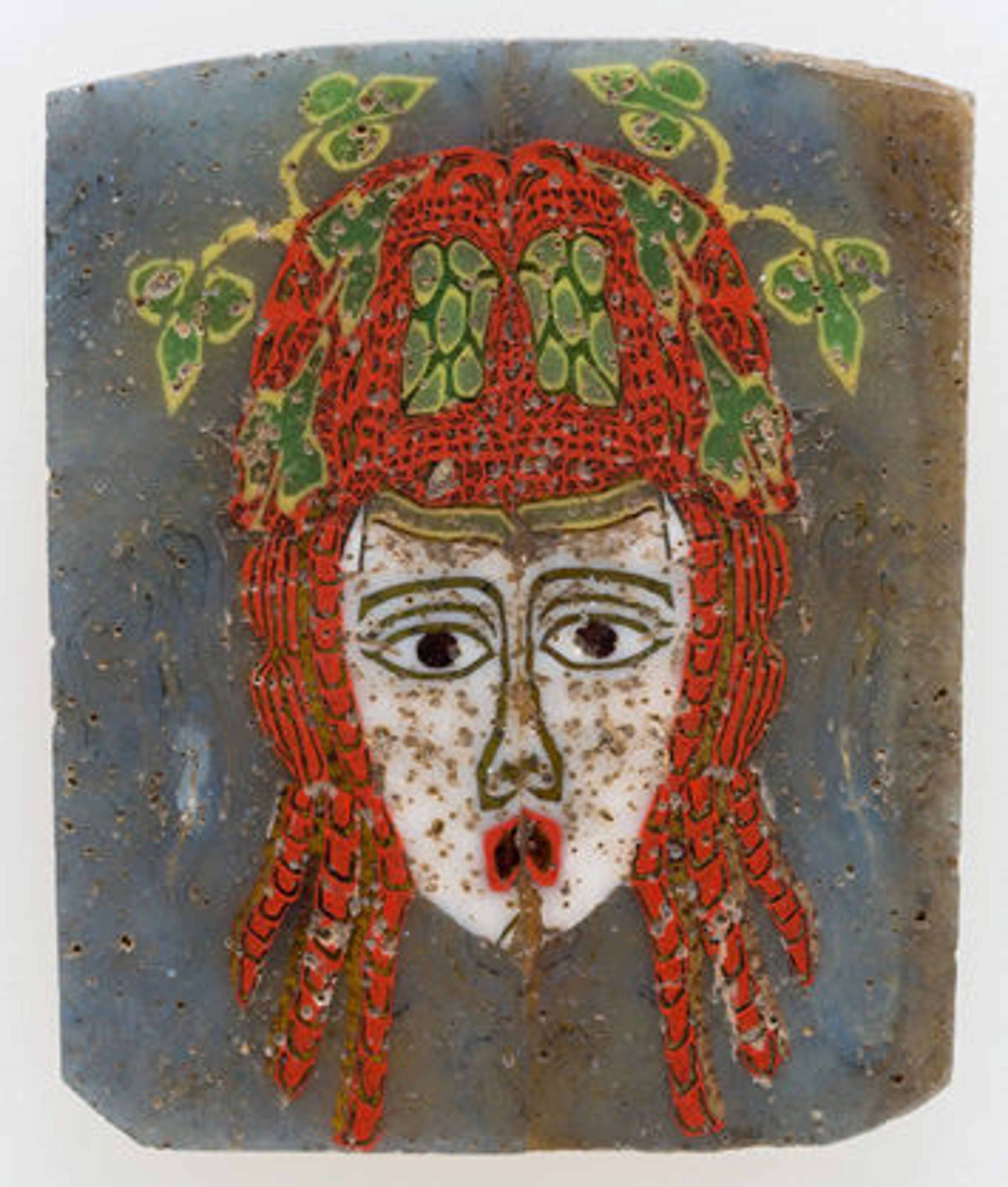

Head Attributed to Arsinoe II. Ptolemaic Period, reign of Ptolemy II and Arsinoe II (278–270 B.C.). Memphite Region, Abu Rawash, IFAO excavations 1922–1923. Limestone (Indurated); H. 12 cm (4 3/4 in.); W. 9 cm (3 9/16 in.); D. 9 cm (3 9/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, 1938 (38.10)

«After many years of study and planning and a yearlong closure for construction and transfer, the new installation of galleries 133 and 134 for Egyptian Ptolemaic art opened today. In them, beloved objects that occupied the old arrangement for 40 years—including the small head of Queen Arsinoe II, a wonderful owl plaque, the Book of the Dead of Imhotep, and many other intense and delicate creations of Egyptian culture at the time it converged with equally vital Greek culture—return to fresh, attentive display.»

The Ptolemaic Background

The Ptolemaic Period began in 332 B.C., when the Macedonian Greek Alexander the Great conquered Egypt, which at that point was ruled by the Achaemenid Persians. With the deaths of Alexander and his immediate heirs, rule of Egypt passed to his general Ptolemy and Ptolemy's descendants. The death of Cleopatra VII and the Roman takeover in 30 B.C. marked the end of the Ptolemaic Period.

Right: Plaque, female face. Ptolemaic Period–Roman Period (100 B.C.–100 A.D.). Glass; H. 3.1 x W. 2.6 cm (1 1/4 x 1 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Edward S. Harkness Gift, 1926 (26.7.1203)

The Ptolemies acted as Egyptian pharaohs, attending to temple building and the traditional Egyptian cults, including animal cults and priesthoods. Age-old Egyptian temples continued to form the centers of towns, and the view of the grand temples and public practices connected to them continued to dominate most lives. But the Ptolemies were also very much Hellenistic kings (see the exhibition Pergamon and the Hellenistic Kingdoms of the Ancient World), inhabiting the new, heavily Greek city of Alexandria on the Mediterranean coast and celebrating Hellenistic ruler cults alongside divine ones in Egyptian temples. Looking at the society more broadly, a Greek element that was already long present and significant, particularly in military and trade areas, received a new influx, and "Greekness" acquired new status that shifted social hierarchies. The two different cultural styles interacted to relay values that varied by region, circumstance, purpose, and individual.

Evoking Two Vantage Points

In the new galleries, we wanted to display the objects in a way that would convey the texture of the period, so two vantage points anchor the display. One focuses on temples, grand constructions that stood physically at the centers of Egyptian towns. The temples act as markers of the larger population, who filled towns or toiled on the river and farms and thus acquired little wealth and left little trace of existence. These populations are more prominent in modern archaeology, where attention to settlements and cities tracks their presence.

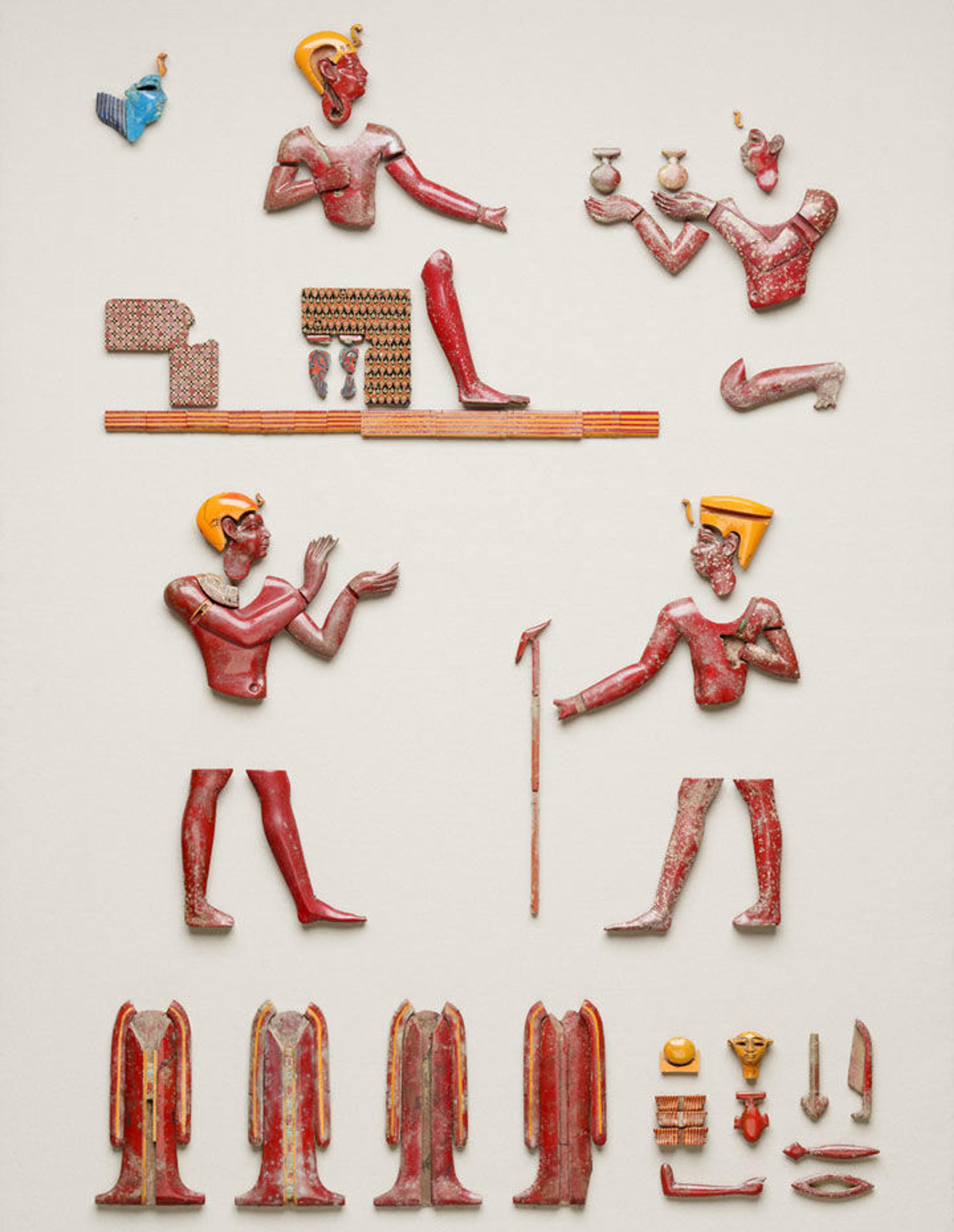

A display in the galleries that features Osiris with faience polychrome tiles from a chapel

The object display devoted to temples is dominated by a set of faience polychrome tiles arranged as they originally would have been around the doorway of a chapel: with a large Osiris statue at the center and silver and gold vessels and jewelry offerings beneath. Small statuary of gods from Thoth and the rarer Nehemetaui to Isis and the child Horus are nearby, as are elaborately wrapped animal mummies, the donation of which was a major practice of the period. Former College Intern Irene Soto, who is now finishing her PhD in ancient studies, intensively studied and consulted with Met staff and outside experts about a group of X-radiographs of these mummies that were taken by Department of Objects Conservation staff to determine their contents, including one that turned out not to be a cat, as long thought, but a dog.

Left: Statue of a goddess, probably Nehemetaui or Nebethetepet. Late Period–Ptolemaic Period, Dynasty 27–30 (550–300 B.C.). Cupreous metal; H. 17.8 x W. 4.3 x D. 10 cm (7 x 1 11/16 x 3 15/16 in.); H. (with tang): 20 cm (7 7/8 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Edward S. Harkness Gift, 1926 (26.7.845). Right: Sacred animal mummy containing dog bones. Late Period–Roman Period (ca. 400 B.C.–100 A.D.). Western Desert; Kharga Oasis, el-Deir, Roman Cemetery. Dyed and undyed linen, animal remains, mummification materials; H. 28 cm (11 in.); W. 6.5 cm (2 9/16 in.); D. 10 cm (3 15/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1913 (13.182.50)

Featured among the other temple accoutrements is a set of glass and bronze elements belonging to a small ancient shrine, perhaps a processional shrine. Cult equipment such as statues and shrines were buried together in temple courts after long use, and objects that had wood as a major component, like small shrines, would decay into a bewildering mass of small fragments. I studied and arranged some of these fragments to make a sensible pictorial arrangement of glass figural elements as Collection Manager Liz Fiorentino devised schemes to track the tiny bits through their shifting arrangements.

Inlays and shrine elements. Late Period–Ptolemaic Period (380–30 B.C.). Glass, cupreous metal; various measurements for group; H. (each drum) 4.1 cm (1 5/8 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1921 (21.2.2-related)

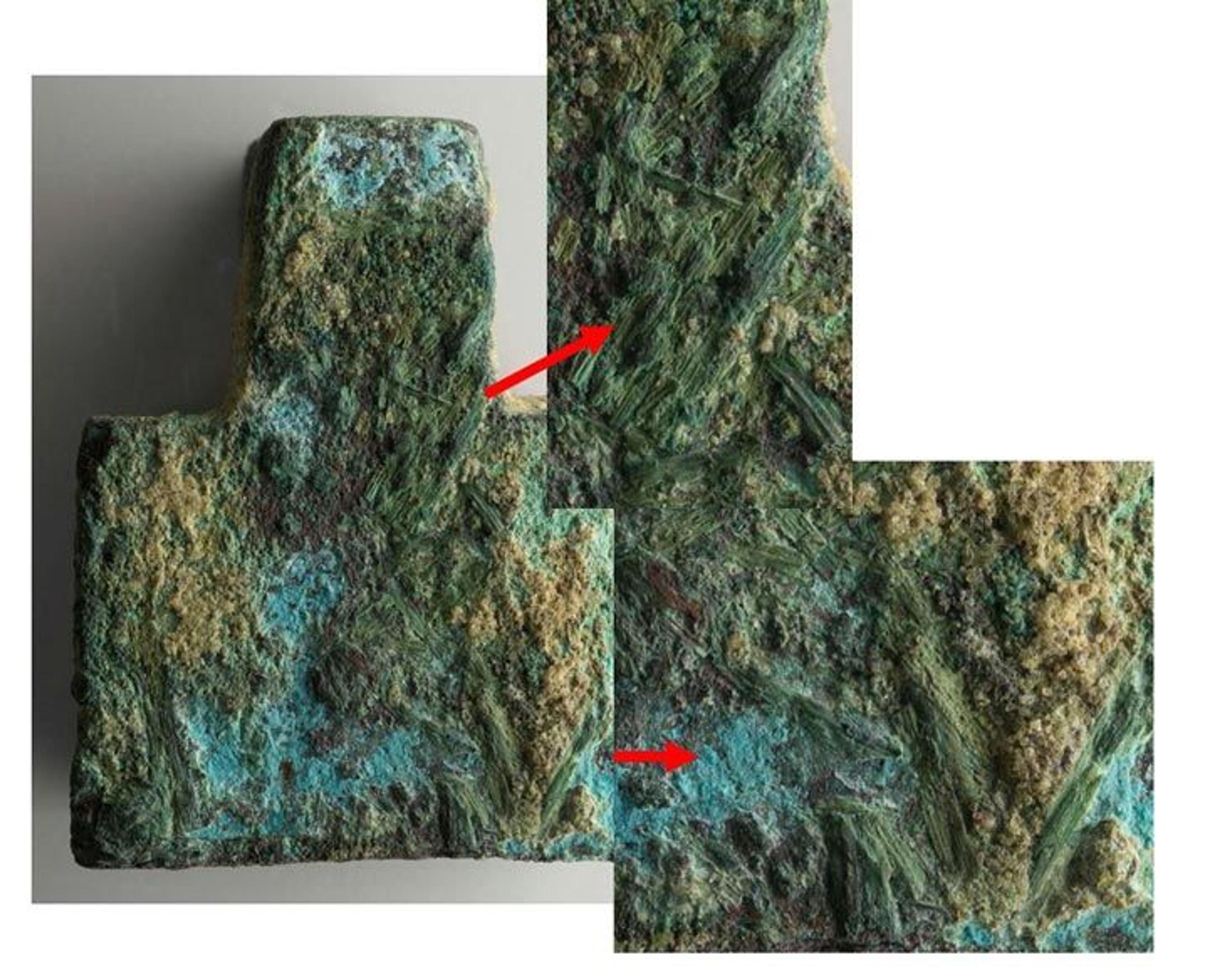

Conservator Ann Heywood carefully examined the column drums in the set and was able to determine that they had laid still on a rod in the ground and could establish their stacking order, which we replicate in the display. The bronze fittings clearly had been caps on the ends of wooden beams, traces of which remained in their interiors. In examining them closely, Ann also found fiber pseudomorphs, or corrosion taking the form of fibers that have decayed away, on their exteriors in a crisscross pattern indicating rope lashings. We know that bronze gods and temple equipment may have been in use for hundreds of years, so it is likely that these elements were originally part of a shrine constructed of bronze and wood, gilded and inlaid with glass figural elements, that became loose at the joints over years of use and had to be lashed tight again.

The fiber pseudomorphs Conservator Ann Heywood found on the bronze fittings

Larger objects placed around the gallery reinforce the temple environment, most notably a small Hathor column retaining enough color to permit a digital color reconstruction and a grand quartzite temple relief.

The second vantage point focuses on the art produced for and representing individuals of the period, from royalty to the official and priest classes. Kings were depicted in Egyptian style, Greek style, and mixed style, according to politico-religious goals. And the immensely important Ptolemaic queens, who represented the dynasty's continuity of rightful inheritance from Alexander, appear in statuary and in portraits on fragments of the sky-blue faience wine jugs that were connected to their cults.

Left: King's head with Egyptian headdress but Greek hair and features. Ptolemaic Period (2nd century B.C. or early 1st century B.C.). Gabbro; H. 6.6 cm (2 5/8 in.); W. 7 cm (2 3/4 in.); D. 5.3 cm (2 1/6 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Gift of Henry Walters, by exchange, 2008 (2008.454). Right: Head, Ptolemy III (?). Ptolemaic Period, reign of Ptolemy III Euergetes I (246–222 B.C.). Faience; H. 4.4 cm (1 3/4 in.); W. 3 cm (1 3/16 in.); D. 2 cm (13/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Peter Sharrer, 1981 (1981.450)

The Museum's wonderful collection of relief plaques and busts are also highlighted. Their use and users are unclear, but the objects themselves appear to be intended to underscore the "pillars" of Egyptian tradition, depicting deified forms of kingship and select popular gods and seemingly fetishizing temple elements and hieroglyphs. Statuary and reliefs belong to functionaries from Karnak Temple at Thebes and from Hermopolis, two flourishing sites in Upper Egypt.

Left: Royal bust with atypical snake. Late Period–Ptolemaic Period, Dynasty 30 (400–200 B.C.). Alabaster (gypsum); H. 12 cm (4 3/4 in.); W. 10 cm (3 15/16 in.); D. 4.3 cm (1 11/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. William H. Moore, 1947 (47.13.2). Right: Model of a temple door bolt with recumbent lion. Late Period–Ptolemaic Period (400–30 B.C.). Limestone; L. 16.4 cm (6 7/16 in.); W. 5.3 cm (2 1/16 in.); H. 7 cm (2 3/4 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of W. Gedney Beatty, 1941 (41.160.103)

Many small artworks that range from adornments for domestic interiors to funerary accoutrements are arranged together, revealing the stylistic spectrum of the period. It is clear that small arts and domestic items more frequently exhibit Hellenistic styles than do items intended for temple or funerary use, at least outside Alexandria.

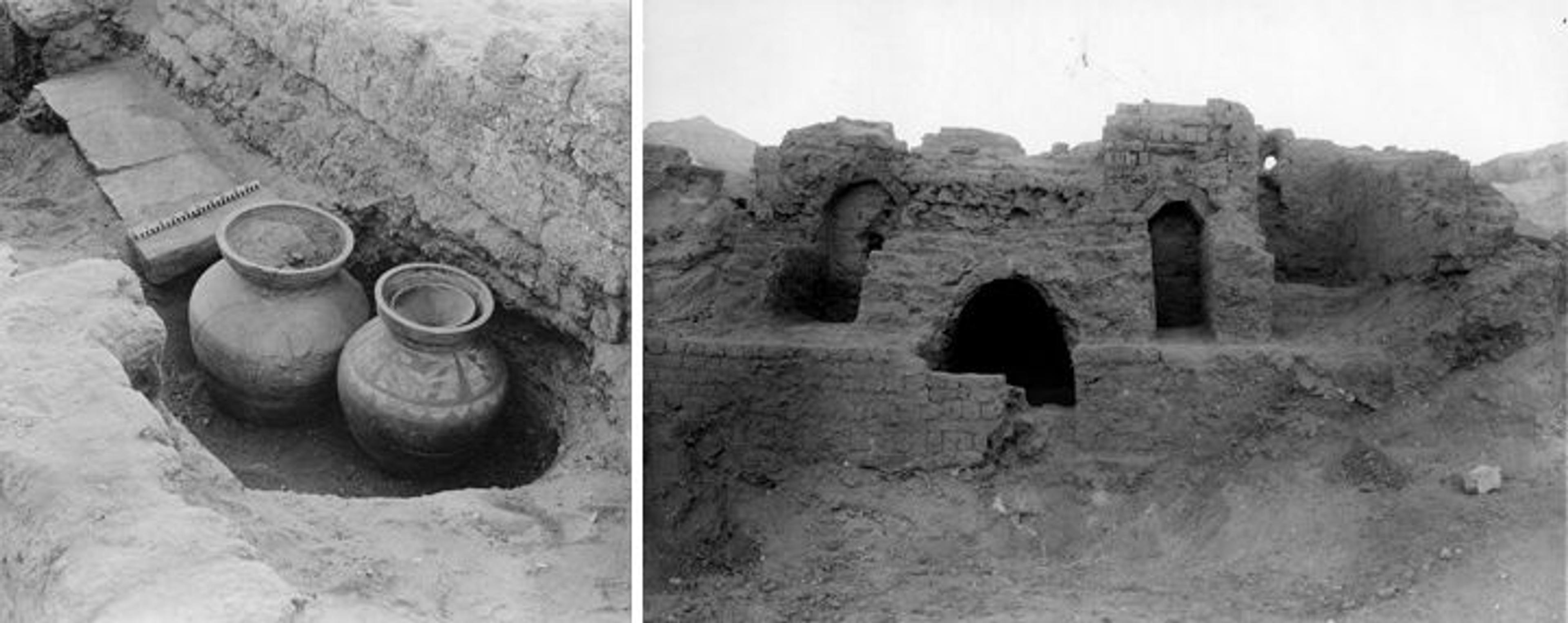

Left: The jars found in the courtyard of one of the tombs. Right: A view of the brick-vaulted tombs in Asasif, Thebes. Photos by the Egyptian Expedition of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

This section also houses finds from The Met's excavations at Thebes in the 1910s in an area of Ptolemaic brick-vaulted tombs—including a huge, beautiful storage jar that stood in the little courtyard of one of the tombs and probably held grain for the deceased, and a bowl in which conservators and scientists discovered remains of the broth that once had filled it. Also found in the area of tombs was a cache of hundreds of coins in a jar, probably buried at a time of uprisings against the Ptolemies in faraway Alexandria but never retrieved.

Large storage jar with floral decoration. Ptolemaic Period (late 3rd–2nd century B.C.). Asasif, Birabi, grave 36, MMA excavations, 1912–13. Pottery, paint; H. 62 cm (24 7/16 in.); Diam. 48 cm (18 7/8 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund and Edward S. Harkness Gift, 1913 (13.180.34a)

Refreshed displays and labeling of two important sets of funerary provisions bring two ancient Egyptians into focus. Curator Janice Kamrin studied the papyri of a priest of Horus named Imhotep, whose Book of the Dead extends over more than 70 feet, and Curator Isabel Stünkel focused on Nesmin, who was a priest for the god Min in Akhmim and whose mummy has been studied using computed tomography. The last case at the south end of the gallery is a visible study collection organized in broad categories, a tradition in our department that allows us to place many more objects on view. Though the labels are brief, visitors can use the accession numbers provided to search the online collection for more information.

The Ptolemaic collection is a wonderful one, achieved through over 125 years of excavations, donations, and purchases. Excitingly, it is now taking a prominent place in the Museum, made possible by the generosity our donors; the prolonged energy and dedication of previous and current department heads Dorothea Arnold and Diana Craig Patch, respectively; and the ingenuity, devotion, and hard work of colleagues in the Department of Egyptian Art and around the Museum who came together to allow every piece to speak. Look out for upcoming blog posts that will delve more deeply into the work that has gone into installing these new galleries and the objects they hold.

Special thanks also to:

Egyptian Art's inventive cadre of technicians: Tim Dowse, Isidoro Salerno, and Seth Zimiles.

Egyptian Art curators Catharine Roehrig and Niv Allon, who spearheaded the presentation of earrings and inscriptions, respectively, although they also magically appeared whenever help was needed.

Oi-Cheong Lee, associate chief photographer, who photographed the pieces in the main display.

Gustavo Camps, imaging design specialist, who photographed the papyri and hundreds of pieces for the online collection.

Deborah Schorsch, conservator, who advanced more precise materials identifications.

Rebecca Capua, conservator, who tended to our papyri and oversaw the remounting of Imhotep’s Book of the Dead

Emilia Cortes, conservator, who prepared the animal mummies.

Museum Preparators Fred Sager, Jacob Goble, Matthew Cumbie, Warren Bennet, and Shoji Miyazawa, who produced a vast number of elegant mounts.

Sanda Heinz, fellow, who was a big contributor to the object study.

Michael Langley, exhibition design manager, who produced the spacious and airy gallery and case design.

Mahan Khajenoori, project manager, who oversaw the complicated construction project.

Taylor Miller, senior associate building manager for exhibitions, who acted as point person and simply made everything work.

Marsha Hill

Marsha Hill is a curator in the Department of Egyptian Art.