The Wrightsmans and the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

James David Draper, Curator Emeritus, Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

Years ago, a fellow curator met an art-loving Frenchwoman who, upon learning his occupation, gushed: "Ah, we so admire your Madame de Wrightsman!" The slip was natural. Jayne Wrightsman set empyrean standards in the world of museums through her legendary largesse and epic contributions to the understanding and enjoyment of European culture, French culture in particular. She backed efforts to maintain monuments not only in France but also in Britain and Russia. She presented a dressing table of Marie-Antoinette by Jean Henri Riesener to the palace of Versailles in 1990, no doubt motivated by longstanding friendships with French museum personnel such as Pierre Verlet and Pierre Rosenberg. She was profoundly touched when made an officier of the Légion d'Honneur in 2013.

Boiserie from the Hôtel de Varengeville, ca. 1736–52, with later additions. French, Paris. Carved, painted, and gilded oak, H. 18 ft. 3 3/4 in. (5.58 m), W. 23 ft. 2 1/2 in. (7.07 m), L. 40 ft. 6 1/2 in. (12.36 m). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman Gift, 1963 (63.228.1)

The relationship of Charles and Jayne Wrightsman to the Metropolitan Museum was long and mutually sustaining. They were clearly drawn to the Museum's gathering together of its finest French objects in period rooms in which boiseries, bergères, and bronze doré light fixtures breathe the same atmosphere as their settings from the loveliest, noblest French houses. They will forever be remembered as creators of the Wrightsman Rooms, inspired by and expanding the spaces occupied by the finely carved and stuccoed enclosures that had belonged to earlier generations of collectors: J. Pierpont Morgan, Mrs. Herbert N. Straus, and Susan Dwight Bliss. In 1956, the Wrightsmans bought two magnificent Louis XV interiors, the Varengeville Room from Paris and the Palais Paar Room from Vienna, with the specific intention of seeing them installed in the Metropolitan, and they presented them in 1963. Their funds enabled makeovers of the rooms in two subsequent phases, ever more sumptuous but ever more authentic evocations of French traditions and inventions, artistry, and taste. These were followed by the Hôtel de Cabris Room from Grasse, a supremely elegant summation of early Louis XVI style. This last gift was genuinely selfless, for its Neoclassical gilt panels had lined their Fifth Avenue dining room. In 1983, the couple endowed the galleries to be open in perpetuity and at all times during public hours. A most welcome recent step was the creation of a Louis XIV room that prompted the conservation and installation of the famous set of embroideries depicting the Sun King and the royal bastards he had by Madame de Montespan, a Museum purchase of 1948. The Wrightsman Rooms have been entrusted to leading designers and decorators. Their last reinstallation, in 2006–7, was carried out with the advice of British theatrical designer Patrick Kinmonth and with lighting that subtly suggests a different time of day for each space.

The Paar Room (gallery 526), one of the Wrightsman Galleries

Although my own specialty is sculpture, the quality, royal provenance, and fame of the Wrightsmans' holdings of French furniture are such that they demand to be discussed beforehand. It was probably Mr. Wrightsman's attorney, Roland Redmond, a longtime trustee and president of the Museum, who introduced them to director James Rorimer and his wife, Kay, and the Wrightsmans, Redmonds, and Rorimers spent much time together. The Rorimers' daughter, Anne, recalls that their reunions were far from stuffy but instead "friendly open-house, probably somewhat impromptu, drop-in gatherings." It was under Redmond's aegis that the Wrightsmans courted another trustee, Judge Irwin Untermyer, and their earliest area of collecting was in his chosen field, English decorative arts. Among their first French purchases, in 1956, were the spectacular Japanese lacquer and gilt-bronze commode and two secretaries made by Adam Weisweiler in advanced Neoclassical taste, acquired by Ferdinando IV of Naples. They continued buying with an eye toward the Museum as their collection's destination. Already in 1957, Rorimer wrote to the furniture expert Pierre Verlet on the Wrightsmans' behalf: "Mr. Wrightsman has expressed a hope that his French 17th and 18th century furniture will one day come to the Metropolitan." By 1962, a letter from the Charles B. Wrightsman Foundation in Texas to the Museum's treasurer could state: "It is now anticipated that Mr. Wrightsman's collection of works of art will ultimately be given to the Museum." In fact, on at least two occasions, the businesslike but gallant husband referred in letters to the collection as his wife's, and he followed her researches with pride, lively enthusiasm, and acumen.

Small desk with folding top (bureau brisé), ca. 1685. Marquetry by Alexandre-Jean Oppenordt (Dutch, 1639–1715, active France); designed and possibly engraved by Jean Berain (French, 1640–1711). French, Paris. Oak, pine, walnut veneered with ebony, rosewood, and marquetry of tortoiseshell and engraved brass; gilt bronze and steel, 30 5/16 x 41 3/4 x 23 3/8 in. (77 x 106 x 59.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, 1986 (1986.365.3)

As an active member of the Metropolitan's Acquisitions Committee, Mr. Wrightsman would certainly have supported the purchase in 1958 and 1959 of a clock and an armoire attributed to the master of Louis XIV design, André Charles Boulle, but the chief thrust was to be the building up of masterpieces from later reigns, Régence to Louis XV and Louis XVI to Directoire and Empire. A quick dip into publications of the collection is like taking an encyclopedic voyage alongside the giants of French cabinetmakers and joiners: Pierre Gole (Louis XIV table veneered with tortoiseshell, ivory, and various woods); Alexandre-Jean Oppenordt, working from designs by Jean Berain (Boulle-work desk from Louis XIV's Petit Cabinet at Versailles); Bernard II van Risenburgh (famous as BVRB, who created several Wrightsman pieces including a bedside table for Madame de Pompadour at Bellevue); Gilles Joubert (the vibrant crimson lacquer and gilt-bronze bureau plat from Louis XV's Cabinet Intérieur at Versailles, for many the most brilliant piece of furniture ever made for that monarch); Martin Carlin (secretary inlaid with Sèvres porcelain plaques that belonged to Czarina Maria Feodorovna at Pavlovsk); Georges Jacob (fire screen for Marie-Antoinette's boudoir at Fontainebleau); Guillaume Benneman (drop-front secretary, a perfect marvel, made for Louis XVI's study at Compiègne, with its mounts by the extraordinary team of Boizot, Forestier, Thomire, and Galle); Jean-Henri Riesener (side table of Maria Feodorovna, wife and later dowager empress of Alexander III, from the Anichkov Palace in Saint Petersburg); and the Frères Jacob (daybed first belonging to Caroline Murat, then to Pauline Borghese, Napoleon's sisters). In their drive for excellence of quality, historic provenance, and stylistic distinction, the Wrightsmans did not spurn lesser-known or anonymous masters. When stirred together by the Wrightsmans' decorators and designers with treasures from the William K. Vanderbilt, Morgan, and George Blumenthal gifts and bequests, their rooms give the most consistently opulent and historically representative overview of French interiors to be gotten outside France.

And this short account barely addresses the seating furniture and the yards and yards of silks and embroideries that the Wrightsmans bought, and the payments they made for dedicated conservators and upholsterers to recover and refresh sofas and chairs, just as it does not address the conservation of the rooms' boiseries. By now, the artisans and technicians underwritten by the Wrightsmans stretch to three generations.

Inseparable from the rooms beyond the furniture are fittings that were added to lend charm and flavor to the overall sense of French aesthetics and utility. They reveal mercury-gilt bronze in all its glory: clocks, including one mounted in a case by the genius of Louis XV rocaille ornament, Charles Cressent; a microscope by Claude-Siméon Passemant, its lenses sheathed in shagreen (skin of a stingray), which very possibly belonged to the scientifically curious king of France himself; a door lock and key, dazzling admixtures of daintiness and solidity, probably Austrian, for the Palais Paar Room; and great quantities of French sconces, candelabra, and chandeliers. Among the chandeliers, I think especially of the superb gilt-steel and rock-crystal construction that proves to have been made by the Milanese Giovanni Battista Metellino. The rooms' mantelpieces are equipped with firebacks, fire tools, and andirons. Many objects, more than mere accoutrements, are great works in their own right, such as the Savonnerie carpet in the Varengeville Room, one of a huge series woven after designs by Charles Le Brun for the Grande Galerie of Louis XIV's Louvre. A delicious grace note is supplied by the iron bracket with the sign of a goldsmith, ordered by Mrs. Wrightsman specially to advertise the Museum's Louis XVI storefront from the Île Saint-Louis, the latter having come as a gift from J. Pierpont Morgan, Jr. in 1920. The storefront's windows contain Wrightsman benefactions such as silver and a terrific oddment, the embroidered leather briefcase, of both French and Turkish manufacture, that was carried by the comte de Choiseul-Chevigny. Deftly distributed books with period bindings are reminders of the intellectual pursuits of many of the rooms' inhabitants.

Elephant-head vase (vase à tête d'éléphant), ca. 1756–62. Sèvres Manufactory (French, 1740–present); designed by Jean-Claude Duplessis (ca. 1695–1774, active 1748–74). French, Sèvres. Soft-paste porcelain, H. 15 in. (38.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, 1983 (1983.185.9)

Meissen and Sèvres porcelains greatly amplify the Metropolitan's holdings, already among the world's most important. An early Wrightsman enthusiasm, inspired by their friendship with Judge Untermyer, was Meissen birds. In 1976, they presented a flock of thirteen, including a fussy cockatoo, and these have recently been regrouped in a stylish vertical setting with the best of the avian species from the Wrightsman Collection joining those from Judge Untermyer and Lesley and Emma Sheafer in the Wrightsman Gallery of Central European Decorative Arts. Wave upon wave of gifts followed. Chinese and Japanese celadon wares lavishly mounted in leafy, European gilt-bronze swirls of ornament, dear to eighteenth-century connoisseurs, are still eminently suitable additions to the tops of ancien régime mantelpieces and cabinets. From the royal Sèvres porcelain manufactory, high points are the garniture of three of the famous vases with elephant heads on an apple-green ground, summations of Louis XV style. These were especially prescient purchases because our friends knew they would one day be seen near the set with rose-pink grounds from the Kress Collection. They also acquired no fewer than 54 items from the original 368-piece turquoise-blue-ground service with exotic birds in landscapes made for the Prince de Rohan in 1771–72. Three vases with chinoiserie motifs but slim Neoclassical proportions, carried out in two colors of gold and the newly exploited medium of platinum on black, were probably bought by Louis XVI in 1791–92, even though he was already in disgrace. In retrospect, Mrs. Wrightsman's taste in porcelains, as in paintings, evolved toward the more simplified and intimate forms of Neoclassicism, and in this she interacted with two curators, the late Clare Le Corbeiller and Jeffrey Munger, being ever sympathetically responsive to their proposals.

I have not yet touched on objects purchased from the Wrightsman Fund, which was responsible for many acquisitions by the department. I think of the pierced gold-and-white Sèvres basket with swans from a later phase of Neoclassicism under Louis XVIII. Mrs. Wrightsman always urged us to sell works that we were disinclined to exhibit, and this truly enlightened attitude has allowed us to embrace new acquisitions from hitherto neglected areas dating far into the nineteenth century as well as tracing backward when works of outstanding merit were offered. Witness our biggest Meissen objects, two charmingly pacific lions modeled by Johann Gottlieb Kirchner about 1732. She also furthered explorations into German Neoclassicism with the purchase of a circular table with a flower-painted top designed by the great German architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Her interest in historicism at Sèvres extended to a pair of Charles X neo-Gothic vases designed by Alexandre Evariste Fragonard, son of the better-known Rococo painter Jean Honoré Fragonard but who became a vital, corrective force in decorative arts associated with the style troubadour. A recent purchase from the Wrightsman Fund is a pair of Dihl et Guérhard vases that reflect the schizophrenia of the Directoire years. Amid their delicate yellow grounds and controlled grotesque traceries, highly original, catastrophic storms at sea and on earth are played out arrestingly in grisaille. When Mrs. Wrightsman agreed to our proposals, my colleagues and I were elated at finding "Wrightsman objects" that won her approval. There could be no higher praise.

Objets de vertu in the collection form a special body of engagingly refined works in gold and other precious materials. Delicate little boxes, chiefly containers for snuff, deserve to be held in the hand for a complete experience. Here are just three standouts: one inset with vistas of the Château de Chanteloup, painted for its puissant proprietor, the duc de Choiseul, by Louis Nicolas van Blarenberghe; that of gold and shell with exotic beings such as a rhinoceros by Louis Roucel; and the massive but wondrously wrought solid-gold receptacle with reliefs of Romulus and Remus and the Roman hero Gaius Mucius Scaevola before the Etruscan king Lars Porcena by a celebrated English master, George Michael Moser. As with the furniture, everyone will have his or her own personal favorite. I am enamored of a toilet service of tiny rock crystal–and-gold vessels with gold spoons and a brilliantly faceted funnel for which the word "exquisite" could have been invented. The Wrightsman Fund has extended our representation of such luxurious objects far into the nineteenth century to embrace such historicizing gems as the clock in the form of a French Renaissance belfry by the clockmaking firm Le Roy et Fils, the goldsmith Léon Chédeville, and the supreme enamelers Bapst and Falize, produced for the passionate English maecenas Alfred Morrison, and a gold-and-enamel paper knife of neo-Byzantine inspiration from the firm of the Roman entrepreneur Castellani.

Clock, 1881. Case and enamel design by Lucien Falize (French, 1839–1897); Clockmaker: Firm of Le Roy et Fils (1828–1898); Case maker: Bapst and Falize; Sculpture by Léon Chédeville (died 1883). French, Paris. Silver, gold, semi-precious stones, amethysts, enamel, diamonds, H. 17 3/4 in. (45.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mrs. Charles Wrightsman Gift, 1991 (1991.113a–f)

Masterpieces bought from the Wrightsman Fund cover several centuries. As the astute and highly effective chairman of the Acquisitions Committee, Mrs. Wrightsman took upon herself a democratic obligation to look beyond the Wrightsman Galleries and to seek and recognize talent and quality in all fields. Our department benefited spectacularly. During Olga Raggio's chairmanship, the Wrightsman Fund supported the addition of three major Florentine Mannerist and Baroque works: the edgy marble bust of Cosimo I de' Medici by Baccio Bandinelli; the architectonic Barberini cabinet inlaid with hardstones; and Massimiliano Soldani's energetic bronze group, The Sacrifice of Jephthah's Daughter. These were followed by demonstrations of German Baroque virtuoso accomplishment. I had long lusted after the wood bust of a general, magnificently bewigged, that belonged to the dealer Ruth Blumka. Philippe de Montebello, who orchestrated acquisitions perfectly in tandem with Mrs. Wrightsman, had to overcome Raggio's objection that we couldn't pretend right then to know who it represents or who made it. Eventually Curator Wolfram Koeppe demonstrated that the bust represents Peter the Great's general and reputed sometime lover, Alexander Danilovich Menshikov, realized in Alexander-the-Great mode, by an unknown Swiss, Austrian, or German carver. The stately, rhythmic mirror inlaid with tortoiseshell and green-stained ivory embellished with silver ornaments by the leading silversmith-sculptor of Augsburg, Johann Andreas Thelot, evokes the glories of the German Baroque palaces that once were.

Probably encouraged by her voracious, wide-ranging reading and curiosity, Mrs. Wrightsman increasingly embraced the offbeat, even when it is showy, as long as it is also eloquent, as witnessed in the Moldovian Baroque silver-and-gilt ewer and basin, exhibiting a host of crosscurrents, that had been deaccessioned from the Hermitage by the Soviets. I suspect that the late Italian Baroque was not entirely to her taste but she nevertheless sportingly funded several rarities of sculptural silver, recognizing how underrepresented Italian silver was at the Met. She agreed to support a gilt-bronze and silver Neapolitan Virgin of the Immaculate Conception; a silver, lapis lazuli, and gilt-bronze holy-water stoup by the Roman Giovanni Giardini with a relief showing Saint Mary of Egypt after a composition by Benedetto Luti; a silver and gilt-bronze relief, The Virgin and Child Triumphing over Evil, probably by the Roman Francesco Giardoni; and a nonfigural work rich in plasticity, a silver-gilt inkstand probably by Andrea Boucheron of Turin. Probably more to her liking are the two gilt-bronze and porphyry candelabra by the Roman Neoclassicist Luigi Valadier, made for the Palazzo Borghese. Somehow or other, it took me a long time to realize that objects bought with the Wrightsman Fund as well as those given cannot be lent, as a matter of legality. Serving for a few days in charge of the department, I unwittingly authorized the loan of the pair to a Valadier exhibition. Mrs. Wrightsman was accordingly less than overjoyed when she received an invitation bearing the image of the candelabra; her displeasure was conveyed firmly but kindly via Jim Parker, and the Museum never repeated the mistake.

Probably by Francesco Giardoni (1692–1757). The Virgin and Child Triumphing over Evil, ca. 1731–40. Italian, Rome. Silver, gilt bronze, and wood; relief: 10 9/16 x 8 7/8 in. (26.8 x 22.5 cm); frame: 23 5/16 x 14 1/2 in. (59.2 x 36.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Wrightsman Fund, 1992 (1992.339)

And so to sculpture, particularly that of the French eighteenth century. The Wrightsmans' marble likeness of the philosophe Denis Diderot, caught in mid-speech by the great artist Jean Antoine Houdon, was rejoined by its pendant from the days when they belonged to the Stroganov collection, after Voltaire's shrewd visage from that collection was sold to them by a friend, Mrs. John Berry Ryan. In an ever more sophisticated market, true discoveries have grown noticeably rarer. In 1990, I happened to recognize from an old publication that a beguiling bust of a sleeping boy coming up for auction in Monaco was by the genial Neoclassicist portraitist Philippe-Laurent Roland. We did the necessary paperwork and Mrs. Wrightsman pledged a handsome sum. I hope everybody was as thrilled as she and I when we secured it for a thirtieth of what she pledged. The consignor sued Christie's for failing to spot Roland's authorship, but we got our boy. In the same year, she bought a marble portrait roundel of a rotund Louis XVI by Roland to go over the mantel in the Louis XVI gallery. Its provenance is the Halle aux Draps, the drapers' hall in the old, virtually stripped marketplace, Les Halles, in Paris. Gradually we have assembled a wonderful cross-section of Roland's oeuvre, including wood panels made for the comte d'Artois at Bagatelle and a strapping bacchante on a goat in terracotta. We shall see that through another friendship of Mrs. Wrightman's we gained one more Roland, his self-portrait, to cap the group. The point is not triumphalism but satisfaction, shared with the donor, at building up a body of work in various media by a modeler of great talent. On the other hand, we had only drawings by another distinguished Neoclassical sculptor, Jean Guillaume Moitte, and she was entranced when I showed her photographs of two spirited terracotta models by him for the portal on the rue de Lille side of the hôtel de Salm-Kyrbourg, now the Palais de la Légion d'Honneur, one of her favorite Paris buildings, and, as so often, she instantly agreed to back the purchase.

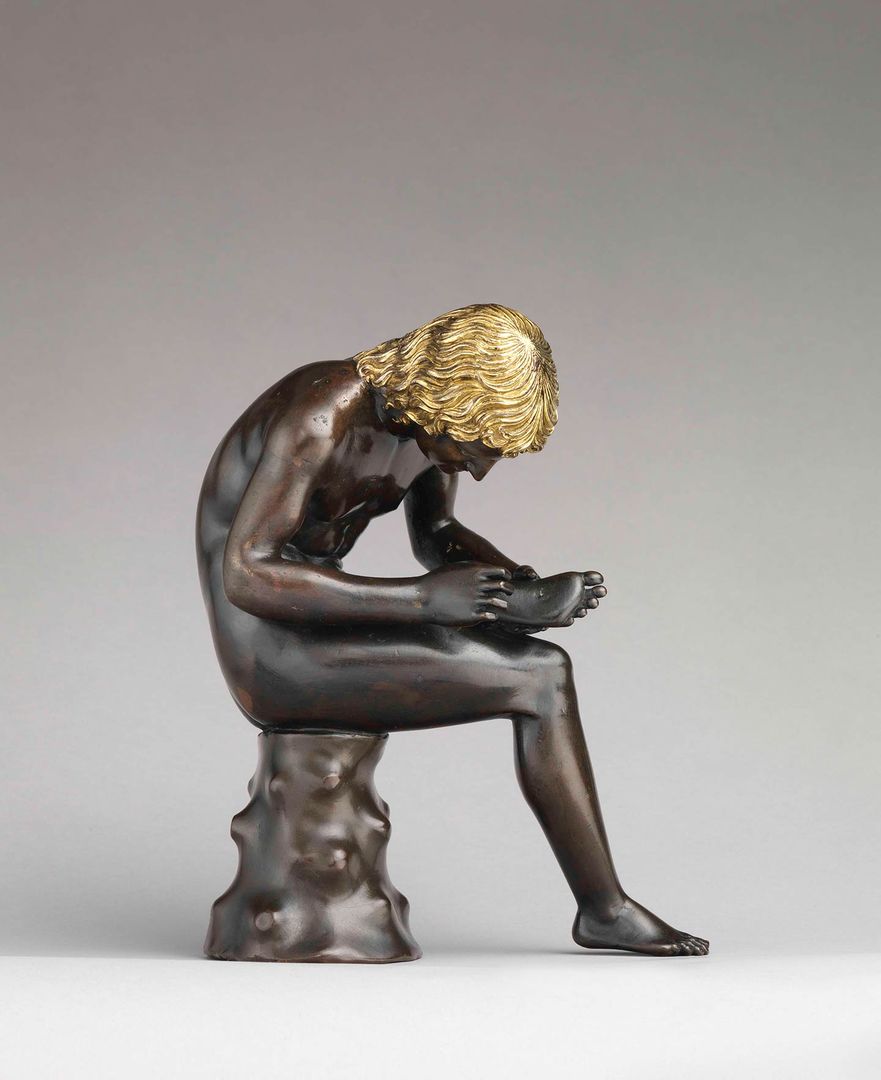

Leaping ahead into the nineteenth century, I was overjoyed and proud when our favorite donor extended her approval to a Second Empire treasure: Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse's enchanting terracotta bust of a young woman in a straw bonnet framed by field flowers. The Wrightsmans' dearest sculptural possession, however, was not French but from the Italian Renaissance: the mesmerizing, partially gilt Spinario by the goldsmith and bronze sculptor in the service of the Gonzaga of Mantua, known as Antico. It is the finest of all reductions of the ancient lad extracting a thorn from his foot in the Capitoline Museum, Rome. It is said to have accompanied the Wrightsmans on their travels, whereas I had always admired it on Mrs. Wrightsman's bedside table. One can well imagine the surge of joy felt by our former chairman, Luke Syson, when she gave it, one of the first acquisitions made in his tenure.

Antico (Pier Jacopo Alari Bonacolsi) (Italian, ca. 1460–1528). Spinario (Boy Pulling a Thorn from His Foot), probably modeled by 1496, cast ca. 1501. Italian, Mantua. Bronze, partially gilt (hair) and silvered (eyes), H. 7 3/4 in. (19.7 cm), W. of base 2 15/16 in. (7.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, 2012 (2012.157)

The Wrightsman name usually stands alone on a Museum credit line, but in 2011 Mrs. Wrightsman gamely teamed with other trustees and friends for the purchase of a magnificent pair of Georgian cake baskets by John Edwards II, originally in Burghley House, presented in honor of our then outgoing chairman, Ian Wardropper, now director of the Frick Collection. She has also inspired numerous gifts made in her own honor. In 1998, she was celebrated with the presentation by the Annenberg Foundation, formed by Walter H. Annenberg and his wife, Leonore, of the suave marble self-portrait by the same Philippe-Laurent Roland. Mercedes Bass had begun choosing objects as tributes to Mrs. Wrightsman in 1995. It has been a challenge for Mrs. Bass and the curators to identify things worthy of the Wrightsman name, but the results have been both glamorous and illustrious: a chaste Sèvres bowl designed for the sampling of dairy products from Marie-Antoinette's laiterie at Rambouillet; a Sèvres ewer and basin whose flowers and speckled porphyry grounds belie the severities of life under the Directoire; an all-white statuette of a finch from the Chelsea manufactory; and a milk-glass potpourri vase and cover with forceful gilt-bronze mounts designed by the aforementioned Schinkel. Another confidante, Barbara Walters, designated a dazzling Empire satin and velvet hanging from Lyon in Mrs. Wrightsman's honor. And a team of friends—Annette de la Renta, Mercedes T. Bass, Beatrice Stern, Susan Weber, William Lie Zeckendorf, Alexis Gregory, and John and Susan Gutfreund— joined forces to assist the museum in acquiring a longcase equation regulator to honor Mrs. Wrightsman. Signed by clockmaker Ferdinand Berthoud, this work was originally presented to the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris in April 1752. The curved case designed by Balthasar Lietaud is in keeping with the rococo style and highlights Berthoud's technical skill. Yet more friends, Mr. and Mrs. Henry R. Kravis, sponsored the splendid 2010 volume, The Wrightsman Galleries for French Decorative Arts, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, by Daniëlle Kisluk-Grosheide and Jeffrey Munger, that surveys the Wrightsman Rooms and their contents.

In sum, in sculpture and the decorative arts, as in paintings, drawings, books, and costumes, the Metropolitan and its public have been immeasurably enriched by the passion, discernment, and ceaseless generosity of Charles and Jayne Wrightsman.

Selected Works

See selected works from the Wrightsman Collection in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts.