Reliquary figure

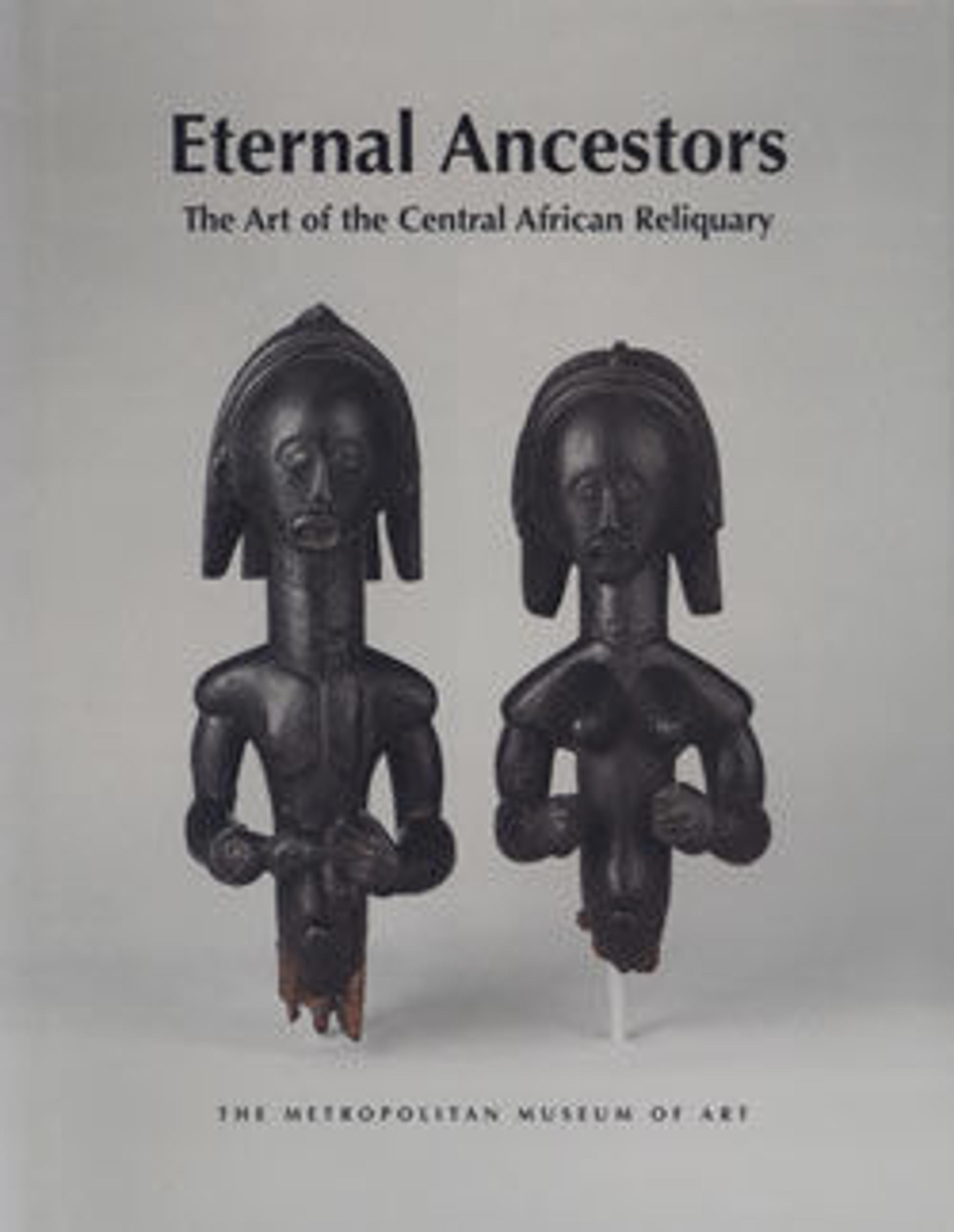

Mbete sculptors developed a figurative reliquary form that fully integrated ancestral sacra within the sculpture. In this tradition, a hollowed columnar torso served as an internal receptacle. That core is framed by the gesture of minimally defined arms held to either side and supported below by knees bent above broad muscular calves. The tensed posture of the figures suggests their role as active guardian to the reliquary's contents. Access to the contents was afforded through a dorsal aperture.

This intensely concentrated figure evokes an active sentinel. The suggestion of arrested movement derives from the slight torsion of the torso and lower body. There is also a slight asymmetry to the placement of the hands on either side of the stomach. The thighs narrow to a point at the bent knees which are supported by powerful muscular calves. Seen frontally, the trunk appears much narrower than it actually is; its full breath is apparent in profile. The reverse side features a long rectangular panel that serves as the aperture to the hollow interior of the torso.

An alternation of black, white, and red applied pigments established at the summit with the coiffure, forehead, and face is repeated on the neck, trunk, thighs, and calves. Especially thick applications of white kaolin have survived in interstices of the arms. The relative flatness of the visage contrasts with the volumetric form of the head. A prominent raised sagittal crest is flanked by lateral tresses carved as a series of deeply incised parallel lines. The smooth crescent of the forehead projects slightly above the lower half of the face that is enlivened by additions of cowry shell eyes and fine metal teeth inserted within the open mouth.

The scheme of black, white, and red pigments applied to the surface of this work and culturally related wood sculptures from the Lower Congo region constitutes a coherent system of color symbolism drawn upon for rites of passage. Black was widely drawn upon in connection with death, burial, and mourning. The ancestral realm is characterized as white, and it is most dominantly manifested in rites relating to vision and heightened awareness such as initiations. Red pomade, a regional cosmetic, was sometimes rubbed on the bodies of the deceased and applied to their insignia to invest them with renewed influence and agency.

This Mbete figure was among the series of full figures collected by French colonial administrator Aristide Courtois for Charles Ratton. The foremost dealer of African art in Paris, Ratton was interested in the potential of the American market. In the 1930s he sold this and a considerable number of other works to Pierre Matisse, the second son of artist Henri Matisse. Pierre had launched his career as an art dealer in New York beginning in 1924 by mounting an exhibition of his father's prints and drawings. By 1931 the Pierre Matisse Gallery represented established European modernists such as Marcel Gromaire, André Derain, Jules Pascin, Georges Rouault, and Marc Chagall in the United States. Eventually the gallery took on the role of promoting and advancing the careers of younger artists, notably Joan Miró, Alexander Calder, Balthus, Alberto Giacometti, and Jean Dubuffet.

In addition to his presentations of his father's generation of artists, Matisse underscored the inspiration they drew from non-Western sources by regularly exhibiting the various traditions referred to at the time in Europe as "primitive art." From March 30 through April 20, 1935 his gallery presented "African Sculptures from the Ratton Collection" at the same time as the exhibition "African Negro Art" was being held at the Museum of Modern Art. While this foray into a new territory of the art world caused him some trepidation, the critics praised his gallery's careful selection and focus on individual works in contrast to the gargantuan presentation of some six hundred works at the Museum of Modern Art .

Further Readings:

LaGamma, Alisa. Eternal Ancestors: the Art of the Central African Reliquary. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007.

Perrois, Louis. "Ambete Art and the ‘Kota’ Tradition." Art Tribal, no. 1 (Winter 2002), pp. 74-103.

This intensely concentrated figure evokes an active sentinel. The suggestion of arrested movement derives from the slight torsion of the torso and lower body. There is also a slight asymmetry to the placement of the hands on either side of the stomach. The thighs narrow to a point at the bent knees which are supported by powerful muscular calves. Seen frontally, the trunk appears much narrower than it actually is; its full breath is apparent in profile. The reverse side features a long rectangular panel that serves as the aperture to the hollow interior of the torso.

An alternation of black, white, and red applied pigments established at the summit with the coiffure, forehead, and face is repeated on the neck, trunk, thighs, and calves. Especially thick applications of white kaolin have survived in interstices of the arms. The relative flatness of the visage contrasts with the volumetric form of the head. A prominent raised sagittal crest is flanked by lateral tresses carved as a series of deeply incised parallel lines. The smooth crescent of the forehead projects slightly above the lower half of the face that is enlivened by additions of cowry shell eyes and fine metal teeth inserted within the open mouth.

The scheme of black, white, and red pigments applied to the surface of this work and culturally related wood sculptures from the Lower Congo region constitutes a coherent system of color symbolism drawn upon for rites of passage. Black was widely drawn upon in connection with death, burial, and mourning. The ancestral realm is characterized as white, and it is most dominantly manifested in rites relating to vision and heightened awareness such as initiations. Red pomade, a regional cosmetic, was sometimes rubbed on the bodies of the deceased and applied to their insignia to invest them with renewed influence and agency.

This Mbete figure was among the series of full figures collected by French colonial administrator Aristide Courtois for Charles Ratton. The foremost dealer of African art in Paris, Ratton was interested in the potential of the American market. In the 1930s he sold this and a considerable number of other works to Pierre Matisse, the second son of artist Henri Matisse. Pierre had launched his career as an art dealer in New York beginning in 1924 by mounting an exhibition of his father's prints and drawings. By 1931 the Pierre Matisse Gallery represented established European modernists such as Marcel Gromaire, André Derain, Jules Pascin, Georges Rouault, and Marc Chagall in the United States. Eventually the gallery took on the role of promoting and advancing the careers of younger artists, notably Joan Miró, Alexander Calder, Balthus, Alberto Giacometti, and Jean Dubuffet.

In addition to his presentations of his father's generation of artists, Matisse underscored the inspiration they drew from non-Western sources by regularly exhibiting the various traditions referred to at the time in Europe as "primitive art." From March 30 through April 20, 1935 his gallery presented "African Sculptures from the Ratton Collection" at the same time as the exhibition "African Negro Art" was being held at the Museum of Modern Art. While this foray into a new territory of the art world caused him some trepidation, the critics praised his gallery's careful selection and focus on individual works in contrast to the gargantuan presentation of some six hundred works at the Museum of Modern Art .

Further Readings:

LaGamma, Alisa. Eternal Ancestors: the Art of the Central African Reliquary. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007.

Perrois, Louis. "Ambete Art and the ‘Kota’ Tradition." Art Tribal, no. 1 (Winter 2002), pp. 74-103.

Artwork Details

- Title: Reliquary figure

- Artist: Mbete-Kota artist

- Date: 19th century

- Geography: Gabon or Republic of Congo

- Culture: Kota peoples, Mbete group

- Medium: Wood, pigment, metal, cowrie shells

- Dimensions: H. 32 1/4 × W. 7 1/2 × D. 7 1/8 in. (81.9 × 19.1 × 18.1 cm)

- Classification: Wood-Sculpture

- Credit Line: The Pierre and Maria-Gaetana Matisse Collection, 2002

- Object Number: 2002.456.17

- Curatorial Department: The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.