During his pre-trial year in solitary confinement, Jesse Krimes experienced “a very deep, intense moment of self-reflection” that confirmed his decision to become an artist: “The one thing they could not take away or control was my ability to create.”[1] Over the course of his six-year incarceration, Krimes made immersive installations that reflect the ingenuity and resilience of an artist working without access to traditional materials. Employing newspapers, soap, cotton sheets, playing cards, and hair gel, he created artworks that recontextualize photographs circulating in the media, prompting questions about which members of society hold power and who is valued.

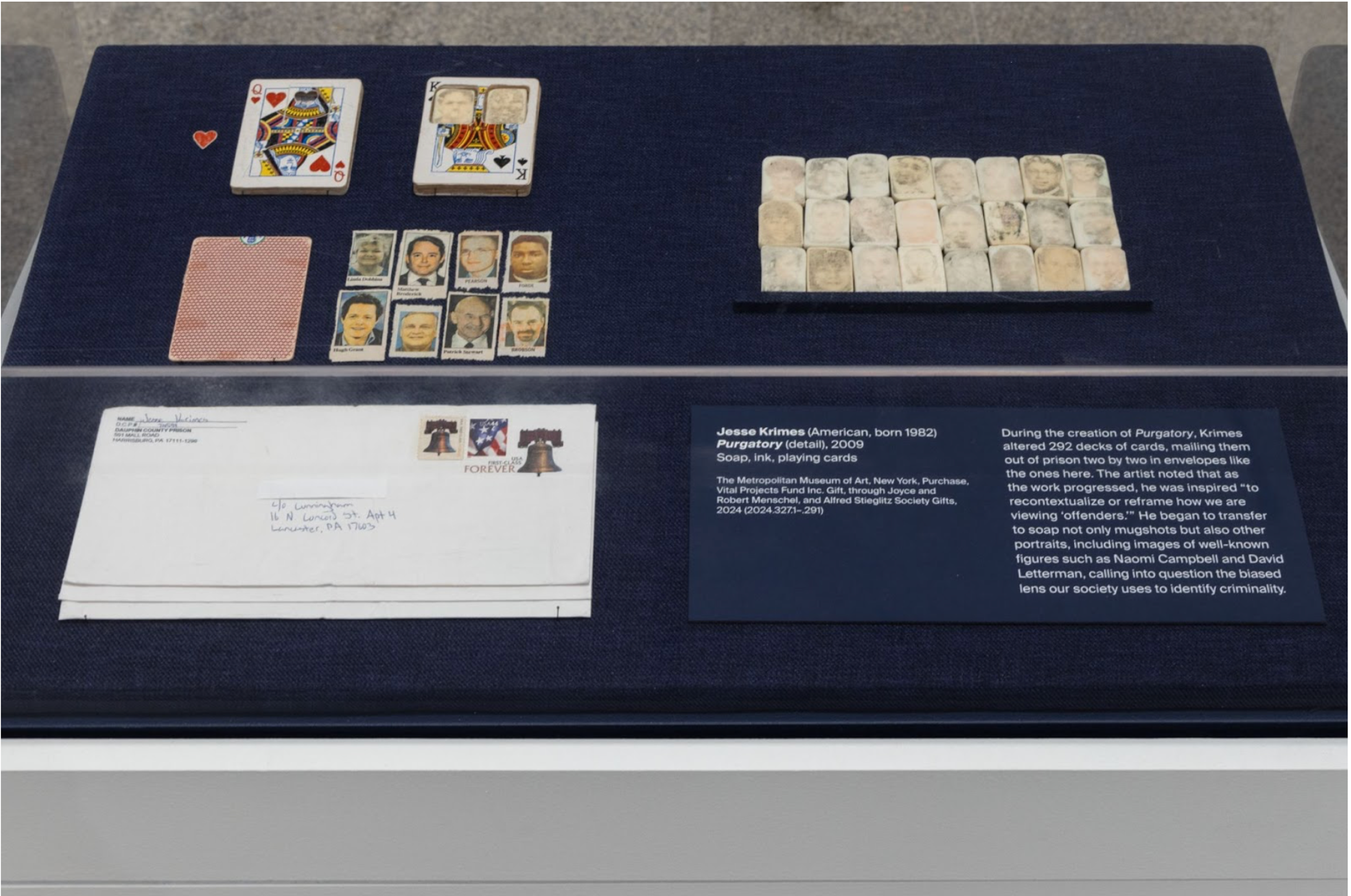

Jesse Krimes (American, born 1982). Purgatory (detail), 2009. Soap, ink, and playing cards [offset lithography], Variable; Image (Soap): approximately 1 1/2 in. × 1 in. (3.8 × 2.5 cm), each Playing cards: approximately 3 1/2 in. x 2 1/2 in. (8.9 x 6.4 cm), each. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Vital Projects Fund Inc. Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, and Alfred Stieglitz Society Gifts, (2024.327.1–.291)

Born and raised in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Krimes was involved in the criminal justice system from a young age. He studied art as an undergraduate at Millersville University of Pennsylvania and was indicted by the U.S. Government on drug charges not long after his 2008 graduation. To pass the time in isolation, he transformed commonplace items into components for an installation that responds to the photographic mugshot. Inspired by Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish (1975), the artist began considering corporal punishment as the primary means of controlling populations. Krimes saw a link between the historic ritual of public hangings and decapitations and the contemporary practice of publishing a suspect’s mugshot in the newspaper, which inspired him “to recontextualize or reframe how we are viewing offenders.”[2]

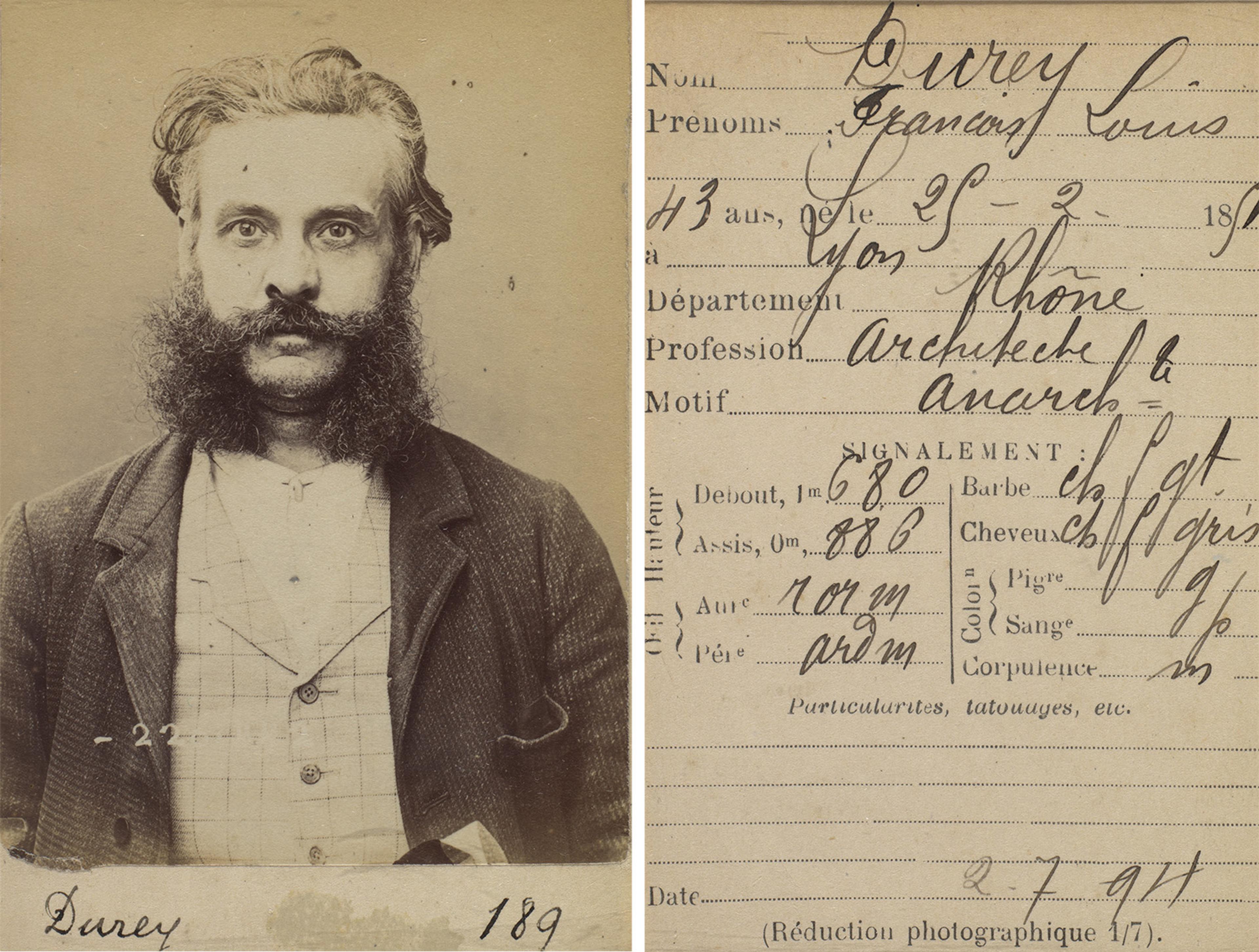

Alphonse Bertillon (1853–1914). Durey. François, Louis. 43 ans, né le 25/2/51 à Lyon (Rhône). Architecte. Anarchiste. 2/7/94., 1894. Albumen silver print from glass negative, 10.5 x 7 x 0.5 cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.) each. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005, (2005.100.375.157)

The modern-day mugshot derives from a nineteenth-century system developed by Alphonse Bertillon, an officer of the Paris Prefecture of Police, to target and identify people charged with crimes. Bertillon’s unique system implemented a pioneering technique called Bertillonage that used eleven anthropomorphic measurements—from the length of the head to that of the left foot, for example—to transform the body into a set of measurable data points. This documentation, paired with notes on distinguishing features and standardized frontal and profile photographs, was compiled to identify recidivists before the utilization of fingerprinting. As the method was adopted worldwide in the 1890s, police invited the public to play a role in surveillance by publishing the photographs and, as the artist and writer Allan Sekula has argued, introducing “the panoptic principle into daily life.”[3]

During his isolation, Krimes sought to question the practice of circulating mugshots in local newspapers. He began to associate the public fascination with criminality with a long history of corporal punishment. For Purgatory (2009), Krimes transferred mugshots published in the local newspaper onto wet 1 ½ x 1–inch soap fragments using a manual printing technique of his own invention. The modest material allowed Krimes to explore notions of penitence and purity alongside the institutional history of cleanliness through one of the only items that was readily available to him. The results vary in intensity and color from faces with legible features to faint apparitions. As the work progressed, Krimes began transferring not only mugshots onto soap but also a range of printed headshots, including images of well-known figures such as Naomi Campbell and David Letterman, to interrogate society’s biases in identifying criminality. The work’s title addresses the artist’s state of limbo at the time of its making and the criminal justice system itself.

Left and right: Jesse Krimes (American, born 1982). Purgatory (detail), 2009. Soap, ink, and playing cards [offset lithography], Variable; Image (Soap): approximately 1 1/2 in. × 1 in. (3.8 × 2.5 cm), each Playing cards: approximately 3 1/2 in. x 2 1/2 in. (8.9 x 6.4 cm), each. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Vital Projects Fund Inc. Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, and Alfred Stieglitz Society Gifts, (2024.327.1–.291)

To keep the soaps from being confiscated, Krimes secured each portrait in a window cut into an altered deck of cards, replacing kings, queens, and jacks with the soap portraits. In a year, Krimes completed 292 decks of cards, mailing them out of prison two-by-two in standard envelopes. By disrupting the hierarchy of the cards through mismatched suits and face cards, Krimes points to society at large, questioning the hands we are each dealt.

Purgatory highlights how power circulates in images and the hierarchies of social imbalance created and reinscribed by our systems of identification. By interrogating Bertillon’s photographic technique, which the state implemented to discipline and control populations and consequently created the singular lens with which we view criminality, Krimes reveals how images can dehumanize their subjects and construct damaging narratives. His work invites a correction to Bertillon’s invention: it rejects oppressive criminal identification methods and recognizes the complex range of human experience.

Jesse Krimes (American, born 1982). Apokaluptein:16389067, 2010–13. Cotton sheets, ink, goauche, colored pencil, hair gel, Overall: 15ft. (457.3 cm) x 40ft. (1219.5 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery (JK.02.a–mm)

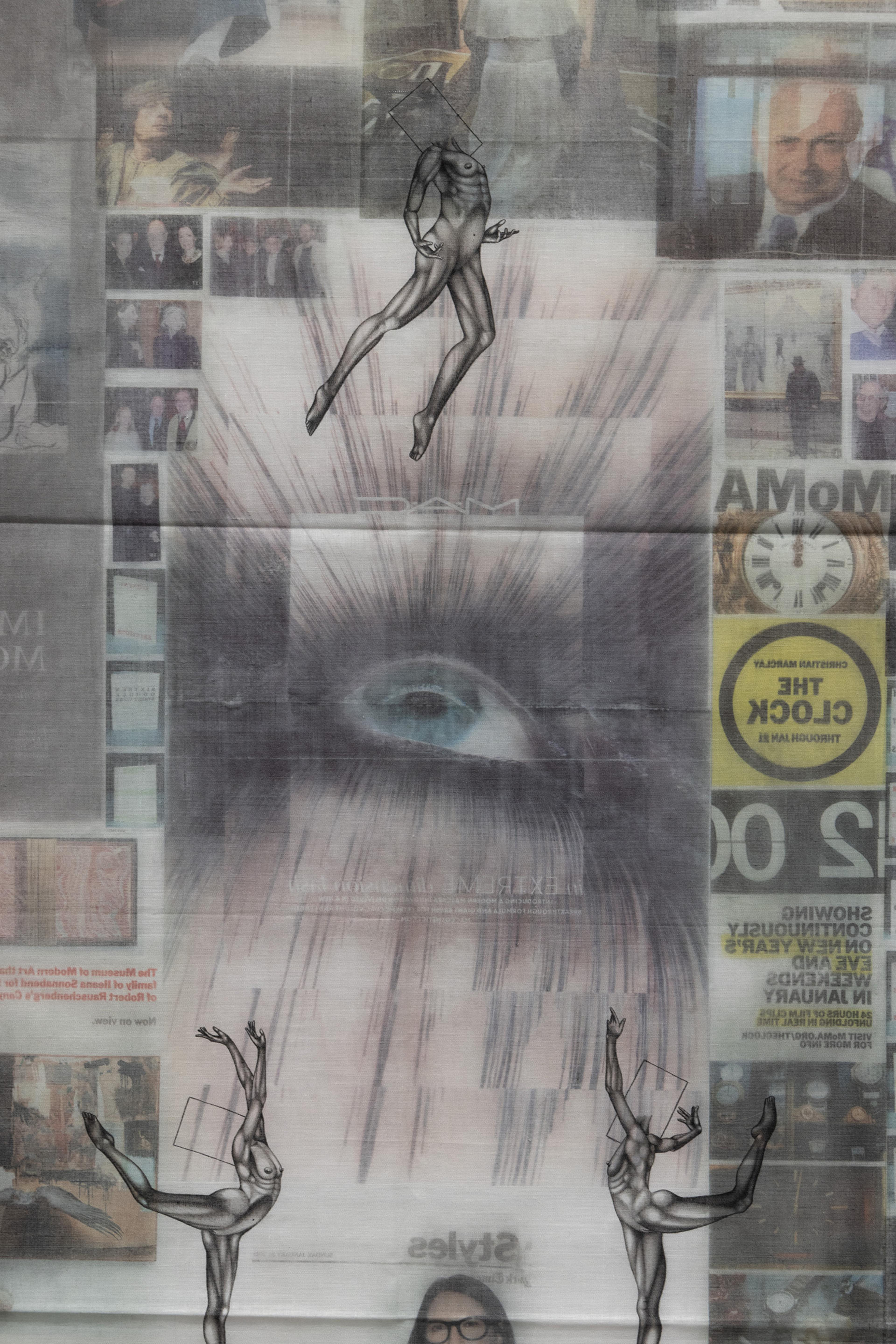

After years of experimenting with his inventive method of image transfer while awaiting trial, Krimes envisioned a large-scale mural in the style of history painting that might present his analysis of how the broad spectrum of images in the media wield influence. The resulting work, Apokaluptein:16389067 (2010–13), presents a surreal landscape of heaven, earth, and hell, through a collage of source images published in the New York Times between 2010 and 2013. He composed the work on thirty-nine bedsheets made by and for the incarcerated, adding hand-drawn elements, and mailed them to a friend on the outside one section at a time. While working on individual panels, Krimes held a vision of the completed piece in his head, but it was not until his release in 2014 that he saw the piece fully realized at Church Studios in Philadelphia.

Inspired by his reading of Giorgio Agamben’s The Kingdom and the Glory (2011), this tripart landscape populated by mediated images of world events offered Krimes an opportunity to depict connections between historical theological ideologies of moral judgment and the contemporary secularized justice system. The work’s title pairs a Greek word (the origin of apocalypse) that means “to uncover” or “to reveal” with the artist’s prison identification number. In the same way that mugshots dehumanize their subjects, in prison, Krimes felt a “loss of identity and this kind of stripping away of all societal markers” noting, “You lose your name; you become this number.”[4] By implementing the format of a multi-panel altar painting in the style of Hieronymous Bosch, the artist likens the power structure of the church to that of contemporary forms of government. What are the checks and balances on power? Who benefits from these systems, or is the system itself at fault?

Jesse Krimes (American, born 1982). Apokaluptein:16389067, 2010–13. Cotton sheets, ink, goauche, colored pencil, hair gel, Overall: 15ft. (457.3 cm) x 40ft. (1219.5 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery (JK.02.a–mm)

With limited access to the outside world, Krimes relied on newspapers as his primary source of information. He discerned a misalignment between journalistic narratives and the symbolism in accompanying photographs. An earthquake, for example, might be followed in the coming weeks by a travel section feature in the same location. To complicate and highlight how we interpret and understand these images, he collected and sorted them to reveal his understanding of the ways visual language describes our cultural value systems. He ultimately chose five categories to build his mural: art objects, commercial advertisements, ideal vacation destinations, man-made disasters, and natural disasters. The new visual narratives extract the photographs (inverted by image transfer) from their original contexts and invite the viewer to experience the outside world through the artist’s incarcerated perspective.

Jesse Krimes (American, born 1982). Apokaluptein:16389067, 2010–13. Cotton sheets, ink, goauche, colored pencil, hair gel, Overall: 15ft. (457.3 cm) x 40ft. (1219.5 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery (JK.02.a–mm)

Hand-drawn female figures inspired by ballerinas and dancers in the newspaper float across the mural’s surface, creating a boundary between the viewer and the world suggested by the images. Their idealized, sculpted bodies seem to arise more from the long tradition of pornographic prison art than from art-historical nudes, functioning in the role of detached observer more as putti than as pinup. Each body is proportional to an identification photograph, like the mugshots used in Purgatory. In the open skies of heaven, the dancing forms bear the heads of male government officials, while colorful bodies on earth host the heads of female pop-cultural figures. In hell, an empty square suggests the absence of intellect while also creating a vessel any viewer might embody.

Like traditional history paintings, Apokaluptein is both expansive and granular. Its images include political and social headlines that remain relevant today, including the election of Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping, school shootings, conflicts in the Middle East, and the disastrous effects of climate change. Some, such as a baroque portrait of Muammar Gaddafi that might have been envisioned by Caravaggio, evoke archetypal stories about power and corruption. Near the center of the mural, one photograph depicts “The Life of Jesus Christ,” a theatrical performance held at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola in May 2012. The play, directed by Gary Tyler, places the incarcerated in roles emphasizing redemption even as they serve life sentences.[5]

Newspaper clippings that Krimes used to transfer images to the bed sheets of Apokaluptein:16389067, 2010–13.

In contrast to paintings of the Last Judgment, for example, in which figures might be sorted into sinners and saved, there is no division within the levels of the collage. Instead, images of disasters, art, political figures, and market economics commingle so that the border between hell and earth is indistinguishable. Commercial advertisements populate the lower level of the terrain, and tension builds across the composition between the documentation of those suffering global horrors and those performing a seductive sales pitch in glamorous outfits with studio lighting. Larger-than-life female models tower over the scene, revealing the oversized presence of slender, blonde, white women in the media. Drawing on art-historical precedents, these shifts in scale suggest symbolic importance just as the repetition of figures creates a sense of narrative propulsion across the length of the panorama. By reconfiguring pictures and their related stories into a three-part landscape of reward and punishment, Krimes compresses and disrupts our visual landscape, suggesting how images can control and influence populations and how we might be complicit.

Incarceration fueled Krimes’s drive to examine the systems of power in our society while also forging the collaborative relationships and providing the ordinary materials he has used to critique it. Since his release from prison, Krimes has sought to make work that cultivates dialogue to challenge and change existing narratives around incarceration. In 2022, he founded the nonprofit Center for Art and Advocacy. Its mission is to highlight the talent and creative potential among individuals who have experienced incarceration and to support and improve outcomes for formerly incarcerated artists.

Jesse Krimes (American, born 1982). Naxos, 2024. Mixed media (including pebbles, thread, and pins), Overall: 14 × 39 ft. (426.7 × 1188.7 cm) [with the 39 panels installed in 3 rows of 13]. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery (JK.04)

The breadth of this interest in collaboration and advocacy can be seen in Naxos (2024), which features nearly ten thousand pebbles gathered from prison yards by incarcerated individuals around the country and shared with Krimes. Each hand-wrapped stone is suspended from a needle by a thread hand-printed with ink to match imagery from Apokaluptein. Installed across from each other, their pairing mirrors and deconstructs that earlier work, serving as a reflection of individuals caught up in the system of mass incarceration. The artist was inspired by the writings of psychologist Carl Jung, who warned of the danger of reducing individuals to statistics: Jung noted the impossibility of finding a river stone whose size matches the ideal average. With each distinctive yet anonymous pebble standing in for the mugshot, Krimes interweaves the complexity of individual experience with the broader social and political context in which mass incarceration exists.

Notes

[1] Jesse Krimes interviewed by the author July 26, 2024.

[2] Jesse Krimes interviewed by the author July 26, 2024.

[3] Allan Sekula “The Body and the Archive,” October (Winter 1986, Vol 39): 10.

[4] Jesse Krimes speaking to Nicole Fleetwood in 2017, from Nicole Fleetwood, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020), 78.

[5] Tyler has since been released from prison and is one of the inaugural fellows of the Center for Art and Advocacy, founded by Krimes in 2022.