Did you know that buildings can tell stories? Buildings can tell us a lot about the people who made them and about what was important to them. By looking closely at the Temple of Dendur, we can learn things about the way the temple was used in ancient Egypt, about moments in Egyptian history, and even about more recent visitors to the temple. Let's take a closer look!

The Temple and the Natural World

Look at the outside of the temple. What details can you find that remind you of things in nature?

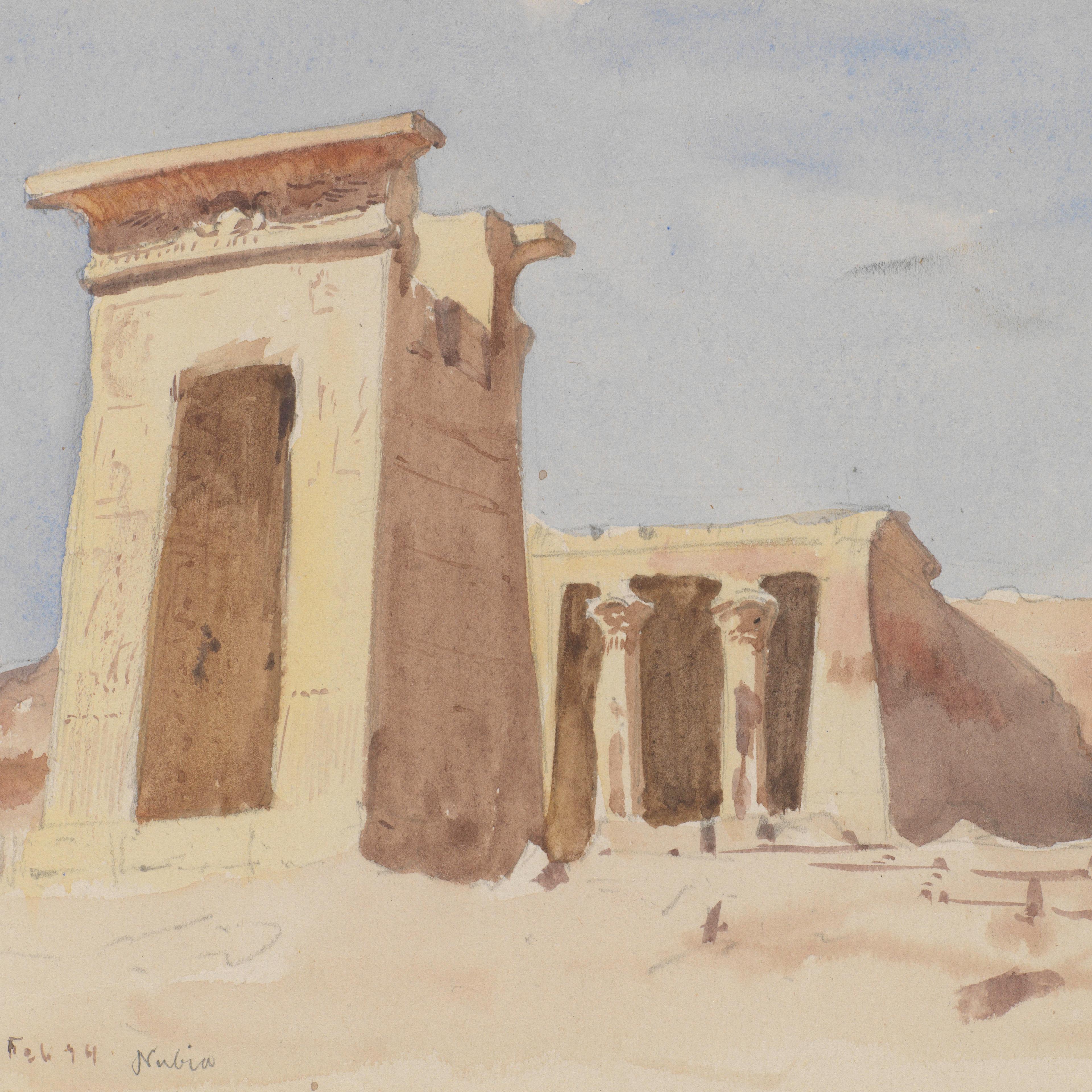

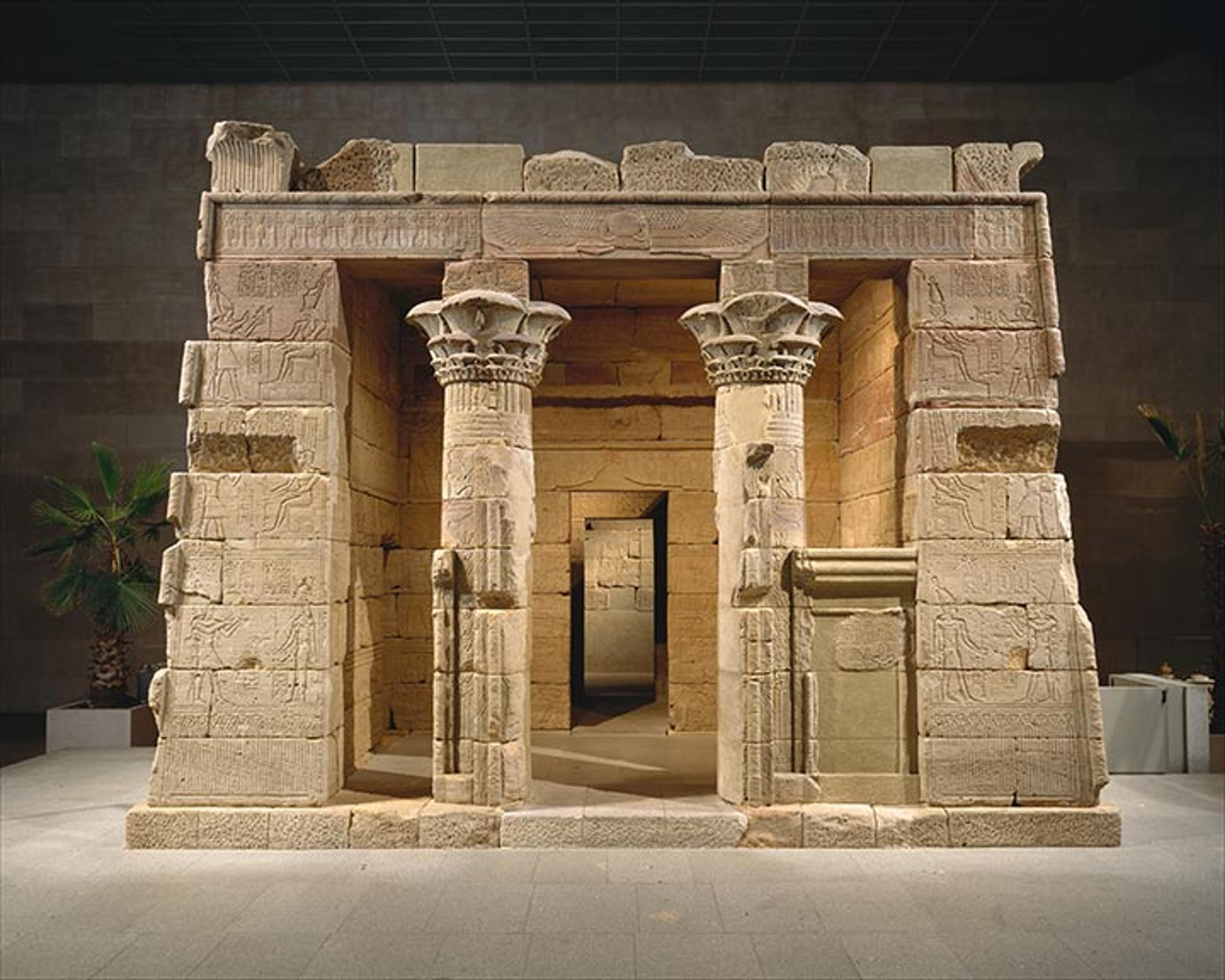

The Temple of Dendur. Roman Period, reign of Augustus Caesar, completed by 10 B.C. From Egypt, Nubia, Dendur, West bank of the Nile River, 50 miles South of Aswan. Aeolian sandstone, Temple proper: H. 6.40 m (21 ft.); L. 12.50 m (41 ft.); Gate: H. 8.08 m (26.5 ft.); W. 3.66 m (12 ft.); D. 3.35 m (11 ft.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Given to the United States by Egypt in 1965, awarded to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1967, and installed in The Sackler Wing in 1978 (68.154)

Egyptian temples often included designs inspired by nature. The base of the temple has images of papyrus and lily plants, which grow in the marshes along the Nile River. The two columns on the porch also rise toward the sky like tall plants. Above the gate and temple entrances are images of the sun disk with the wings of Horus, a sky god who often takes the shape of a bird known as a falcon. The sky is also represented inside the temple by vultures carved on the ceiling. Through these decorations, the temple reflects the world: sky above and earth below.

The sun disk with the wings of Horus, the sky god, located above the entrance to the temple.

The Temple and the Pharaoh

Look at the temple walls. How would you describe the figures that you see? What are they doing?

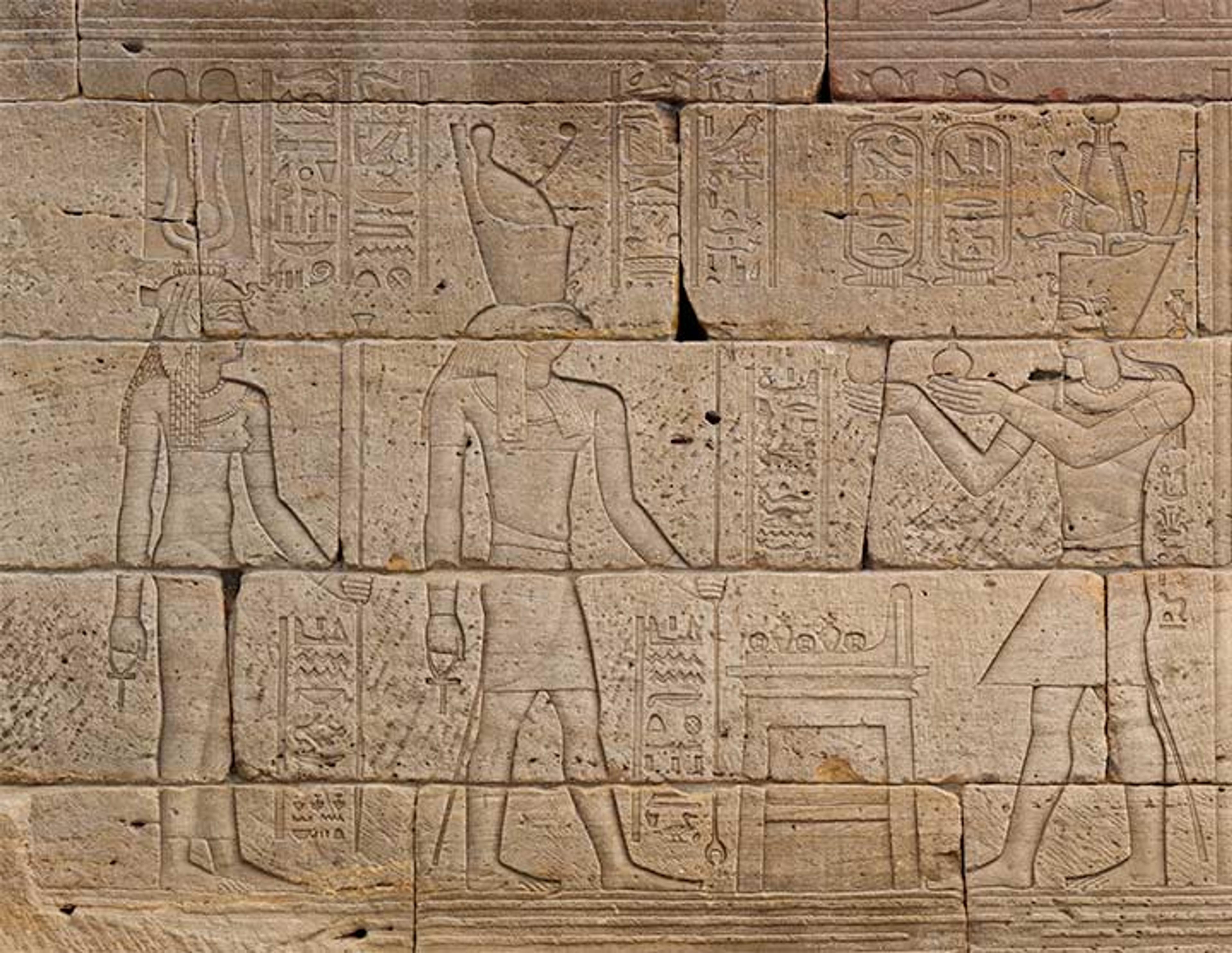

Augustus (on the right) offers jars of wine to the deities Harendotes (center) and Hathor (left).

The temple walls are covered with images of the pharaoh (king) of Egypt. The pharaoh is shown wearing different crowns and a short skirt called a kilt. These items were already used for thousands of years by the time that the Temple of Dendur was built, and many pharaohs were shown wearing them. But the pharaoh shown on the Temple of Dendur was actually not Egyptian at all—he was Roman! The Temple of Dendur was built just after the Romans conquered Egypt. The pharaoh who is shown on the walls of the temple is Augustus Caesar, emperor of Rome.

Augustus (on the right) offers wine to the deities Thoth (center) and Tefnut (left).

Augustus is shown worshipping different gods by offering them gifts like wine and milk. One of the pharaoh's most important responsibilities was to perform certain rituals for the gods every day in the temples. These rituals included bathing, clothing, and offering food to the statues of the gods. Performing these rituals was one of the ways that the pharaoh kept order (ma'at) in the world.

Even though the images on Egyptian temples show the pharaoh performing the rituals himself, in reality it was usually the local priests who did the ceremonies in the temple. After all, the pharaoh could not possibly be in every temple throughout Egypt every day! In the case of Augustus, it is possible he never even went to Dendur.

In this scene on the temple, Augustus is shown worshipping two brothers named Pihor and Pedesi. Pihor is on the right, wearing a headdress with a cobra called a uraeus [yoo-RAY-us]. Above his head is a sun disk. Pedesi wears both a uraeus and a tall crown with ostrich feathers on either side. They both hold an ankh, a symbol of life.

Some of the gods that Augustus is shown worshipping on the walls of the temple are traditional gods of Egypt and Nubia, such as Isis, the goddess to whom the temple was primarily dedicated. But in several scenes the pharaoh is also shown worshipping two figures that are not known as gods in other areas of Egypt. These two figures are Pihor and Pedesi, who may have been sons of a local Nubian ruler. The brothers were probably given the status of gods after they died. Exactly who they were and why they were deified (worshipped as gods) is not known and remains one of the temple's mysteries.

The Temple and the Modern World

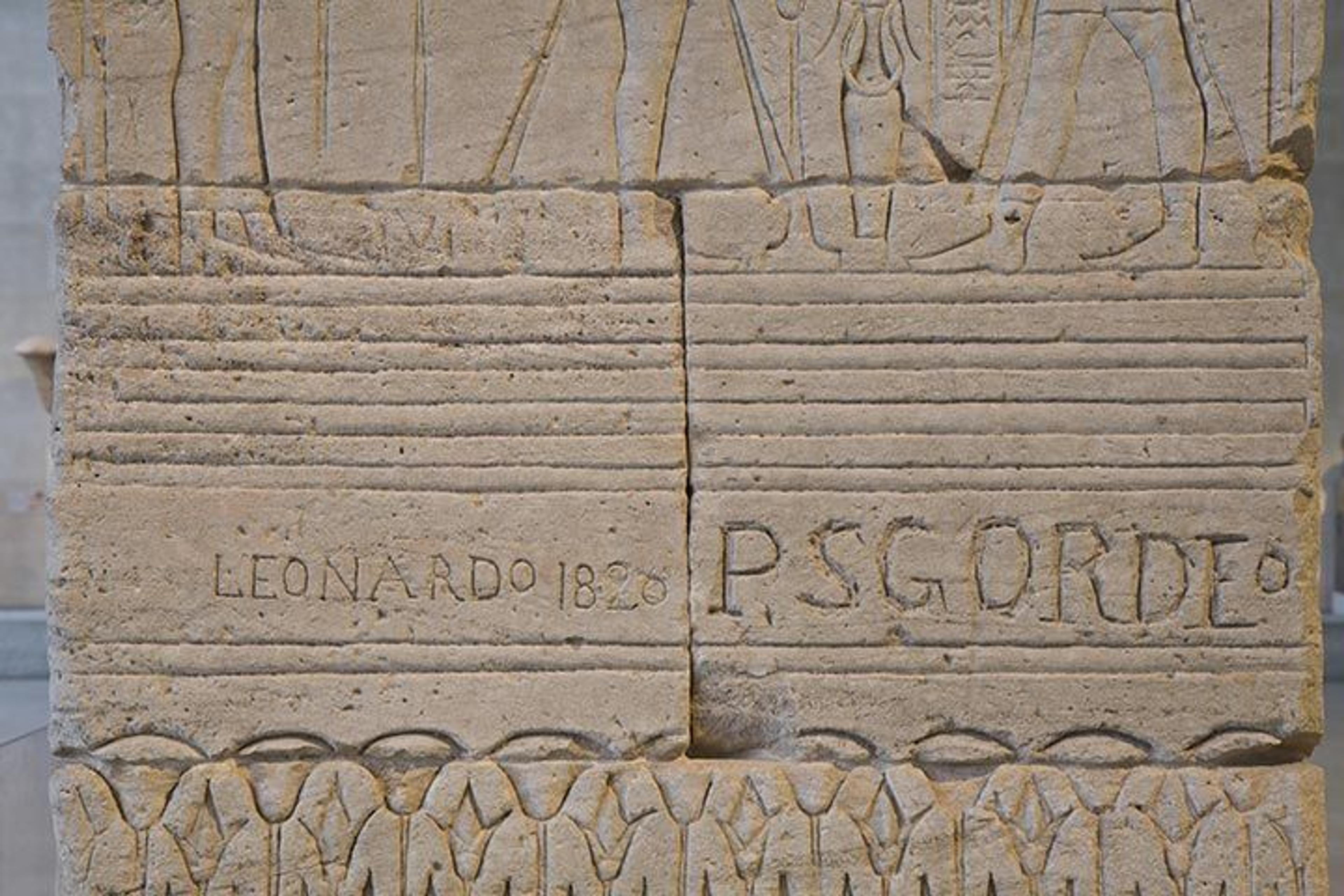

Graffiti on the gate made by visitors to the temple when it was still located on the Nile River in Egypt

Look at the outside of the temple. Do you see the modern names carved over the ancient images? What date is carved next to the name Leonardo? He visited the Temple of Dendur almost 200 years ago, before airplanes were invented. Visitors were impressed and inspired by the beauty of the temple, and often wanted to leave their own mark on it. Many people carved their names onto the walls of the temple to say, "I was here!" Because we want to preserve the temple, we would never add graffiti to the walls today—in fact, we don't even touch it! Even so, the names of these visitors remind us of people who visited the temple when it was still in Egypt.

The gate and temple as seen from across the pool of water in The Sackler Wing

Today, the temple stands in gallery 131 in The Sackler Wing, which has glass windows overlooking Central Park. A pool of water in front of the temple hints at the Nile River, on whose banks it once stood. But how did the temple get from Egypt to The Met?

In the 1960s, the Egyptian government began building a large dam on the Nile at Aswan. As a result, the rising waters would have flooded the Temple of Dendur and many other important sites. To save at least some of these monuments from disappearing, the United Nations started a project to move them safely out of the way. As part of this project, the temple was taken apart—block by block. Egypt gave the Temple of Dendur to the United States as a gift to say thank you for the help the United States gave to the project. It was decided that the temple would come to The Met 50 years ago. In the 1970s, The Sackler Wing was built specifically for the temple, which was put back together—block by block.

Look around your own community. What buildings or monuments do you see? What stories do they tell? Make a picture of a building or monument and write a story about it. Then ask an adult to email your picture and story to metkids@metmuseum.org.