View of the Postern Gate stairs, taken just before the opening of The Cloisters in May 1938. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Cloisters: Photographs 1938. New York, 1938.

«The scope of architectural treasures at The Cloisters museum and gardens extends beyond our extraordinary medieval collection and includes work by the modern-day Samuel Yellin Metalworker studio. In fact, most visitors enter The Cloisters through spaces enhanced by Samuel Yellin (1884–1940), who played a major role in the American Arts and Crafts movement, both as a designer and metalworker. He was extraordinarily prolific, working alternately on an intimate or monumental scale, for private homes or large institutions, in fanciful or restrained styles.»

Samuel Yellin was born in Russia in 1884 and entered the United States in 1900. After apprenticing with a Russian master blacksmith, Yellin became a journeyman and traveled in Europe before immigrating to Philadelphia. He began taking classes at the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art and by 1907 taught a class in "wrought-iron work," a post he held until 1919. He opened his first shop in 1909 with three assistants, eventually moving to a purpose-built studio/showroom at 5520 Arch Street in 1915 (razed in the 1990s). (View works by Yellin on the Philadelphia Architects and Buildings website.) Yellin employed 268 men at the firm's peak in 1928, and the studio received over twelve hundred commissions in the 1930s alone. The concern was called "Samuel Yellin Metalworker" throughout Yellin's lifetime and still exists today as the Samuel Yellin Metalworkers Co., operated by his granddaughter, Clare Yellin.

Yellin's passion for this demanding medium is best demonstrated by his own statements, many of which are collected in Jack Andrews's monograph Samuel Yellin, Metalworker. In a 1926 lecture at the Chicago Architectural Club, Yellin declared: "There is only one way to make good decorative metalwork and that is with the hammer at the anvil." This statement was both one of his favorite aphorisms and the guiding tenet of his studio, where even the draftsmen were taught the basics of blacksmithing to ensure that they understood how a piece was made. Yellin was adamant about working from traditional designs, insisting that past masters "…saw the poetry and rhythm of iron." He also amassed the finest collection of antique ironwork in the country, which served as a study collection for his staff. A number of his medieval pieces were acquired by The Cloisters in 1955 (see an example), and his own work is also represented in the Museum's collection.

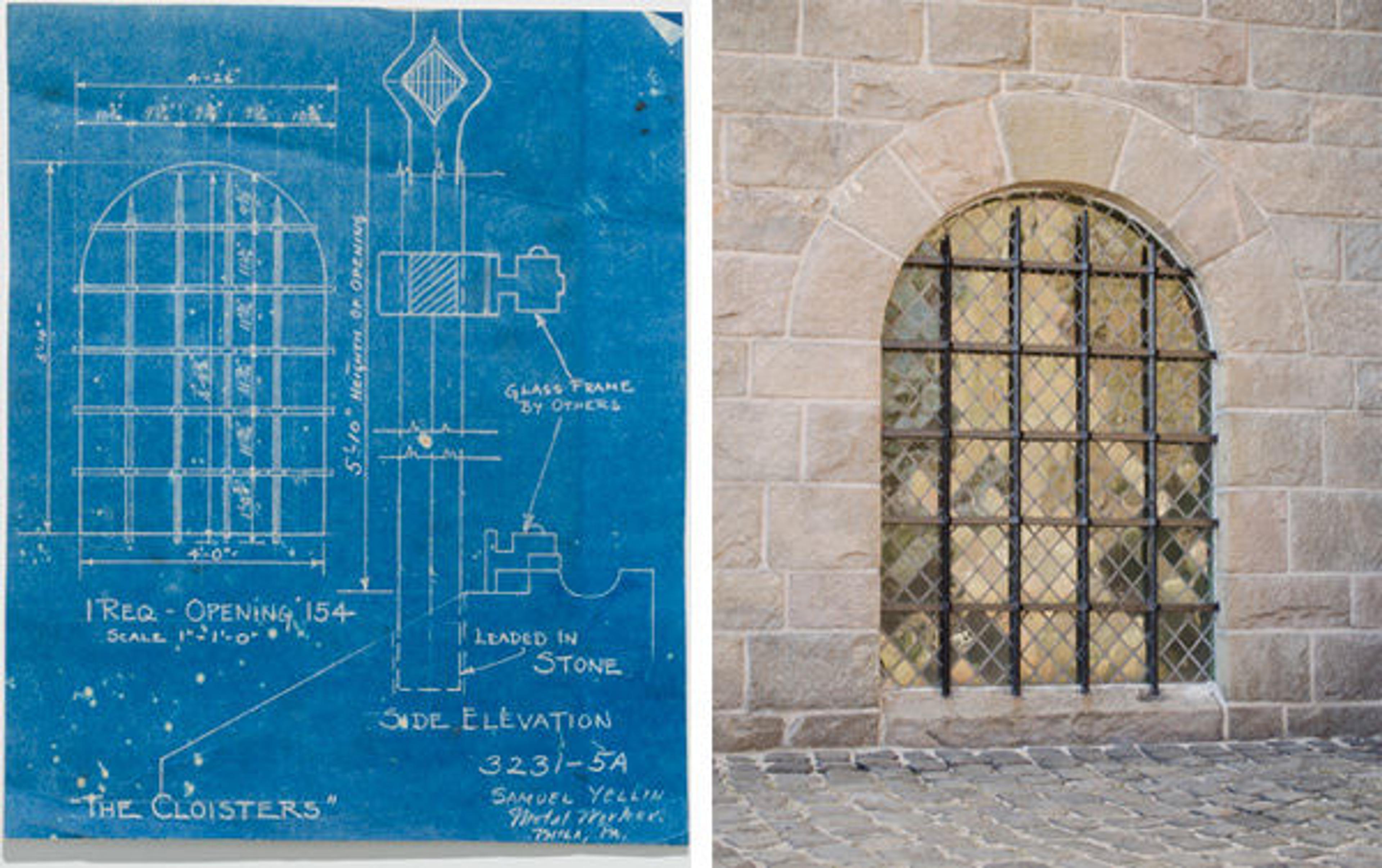

Left: Drawing for a window grille on the Postern Gate stairs. The Cloisters and Fort Tryon Park Architectural Drawings and Prints; The Cloisters Library and Archives, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Right: Window grille as installed at The Cloisters, seen from the interior courtyard. The window is above the final landing at the top of the Postern Gate stairs at the main visitor entrance.

Although Yellin was a prominent artist in his day, it is unclear as to how he came to be connected with The Cloisters. He seems to have initiated contact himself in May 1935, although John D. Rockefeller, Jr. received a letter of introduction from a friend praising Yellin's work at the same time. Rockefeller replied that Yellin was well known and that he would suggest Yellin for consideration if ironwork were needed for The Cloisters. On the same date as the letter written to Rockefeller, Yellin sent a letter to James Rorimer, curator of The Cloisters, and referred to previous conversations, thereby establishing that they had already been in contact with each other. In any event, Rorimer's reply to Yellin was written a mere three days after Rockefeller's letter; in it, Rorimer assured Yellin that the Museum would ask him to submit a bid.

Archival documents reveal that Yellin's 1937 contract included the ornamental railings, grilles, and gates at The Cloisters as well as a number of structural iron door frames, some of which were used to hang medieval wooden doors. Items range from the unassuming decorative pins on our distinctive Portcullis Gates to the whimsical bell frame on the southwest corner of the building. It decorates the very practical chimney required for the boiler. An additional order was placed just after the building opened to the public; the most visible results are the stair rails in front of the Gothic portal from Moutiers-St.-Jean and down the center of the Postern Gate stairs.

Bell frame with pennant installed on the chimney at the southwest corner of the Cuxa Cloister

Yellin's decorative metalwork elements can certainly be appreciated as independent works of art, but they also harmonize with their environment. Iron window grilles naturally restrict access and provide security, but Yellin insisted that ironwork must not be seen as a barrier. Ironwork should instead create a visual bridge between people and buildings, and to the space beyond it.

Gate at the bottom of the Froville Arcade entrance to The Cloisters

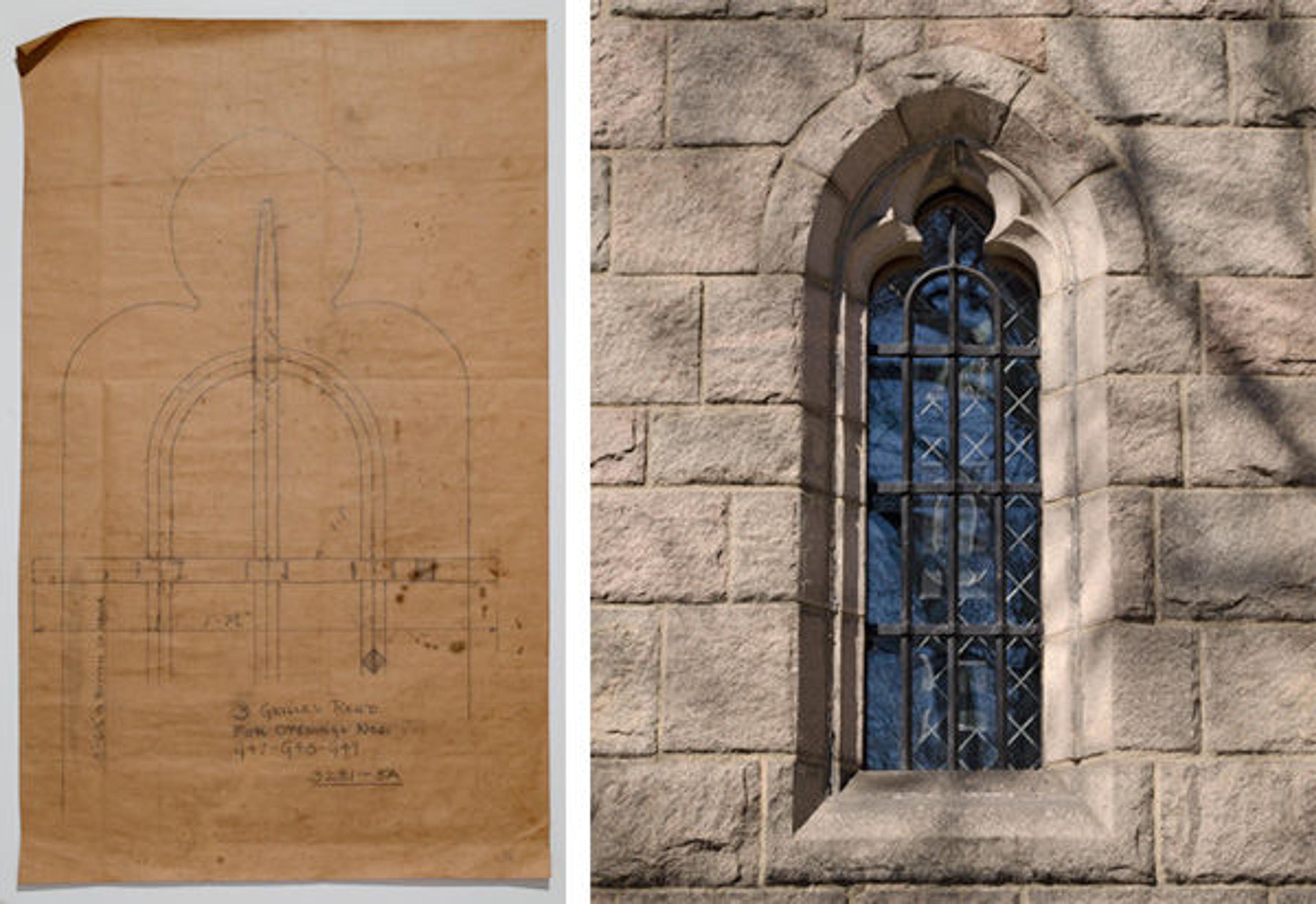

The Yellin drawing from our archives shown below illustrates one of three grilles installed on the east facade, a unique design used only in these windows. Here, Yellin creates a grille that, with its simple, geometric design, is completely sympathetic to the trefoil-headed window. The iron bars are pierced at the intersections, a design that is both technically difficult and typical of Yellin's work at The Cloisters. All of the lower-level windows on the exterior, as well as in the interior courtyard, are fitted with grilles of several different patterns.

Left: Drawing for one of three grilles designed for the Treasury windows. The Cloisters and Ft. Tryon Park Architectural Drawings and Prints; The Cloisters Library and Archives, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Right: Grille as installed in a Treasury window at The Cloisters

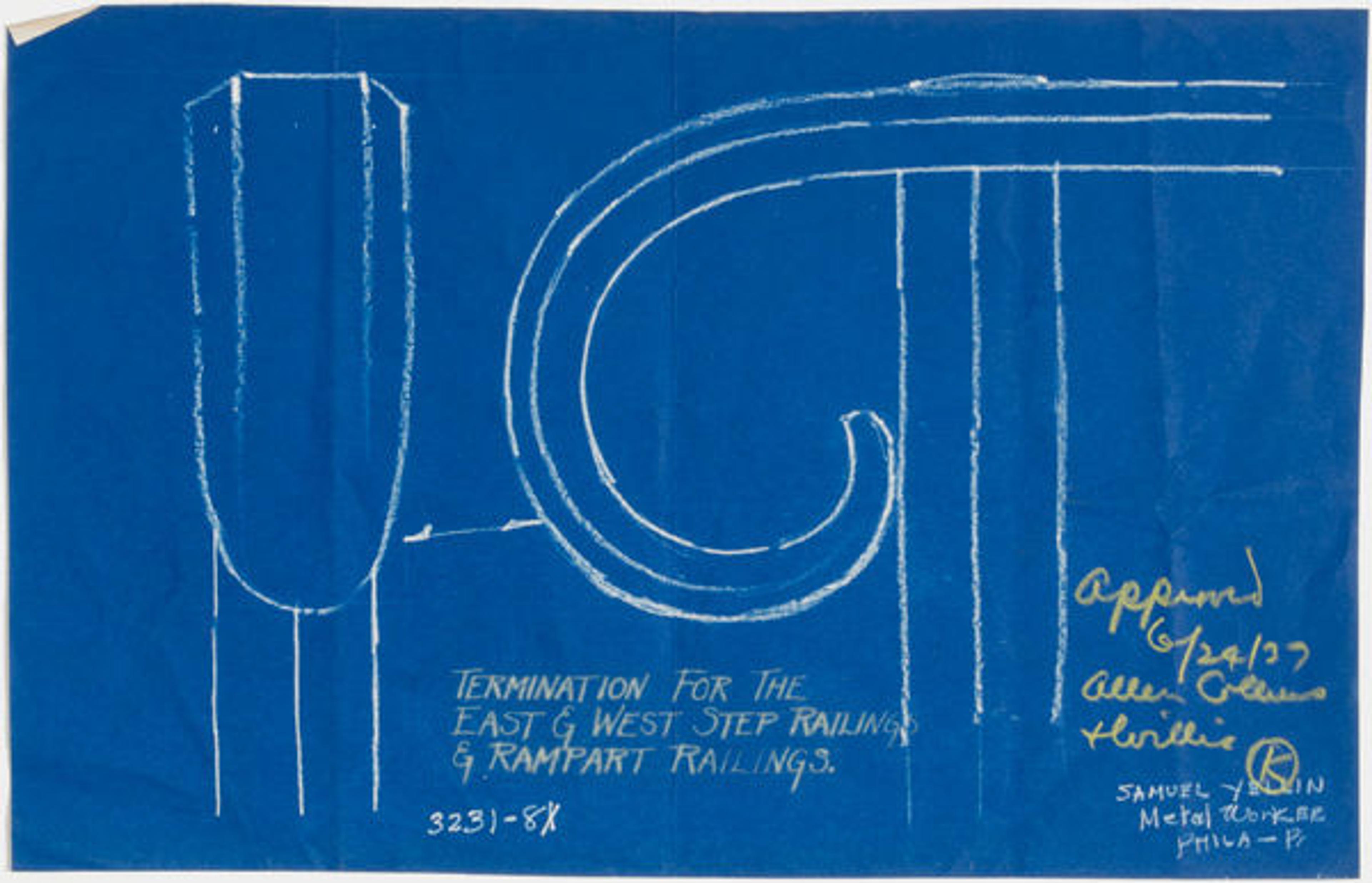

Additional drawings show the standard railing design used both indoors and out. The iron balusters are all square in section and rotated by forty-five degrees, and the handrails are flat, most pierced by the balusters. Most of the handrails terminate in volutes. Balusters on the staircases and on the ramparts railings are pierced at midpoint by a square horizontal rail, also rotated by forty-five degrees.

Drawing for exterior railings. The Cloisters and Ft. Tryon Park Architectural Drawings and Prints; The Cloisters Library and Archives, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The railings are tactile as well as visually appealing. Iron elements are turned, twisted, and pulled, demonstrating the physical process involved in manipulating the challenging material. Tenons are important in Yellin's work; he used them to make explicit the way in which pieces are joined and assembled. They are part of the design, providing texture and dimension to the tops of the handrails or edges of the gates. Yellin maintained: "All of my work is honestly and simply done, whether it be visible in the finished product or not, and the nature of the material is truthfully expressed both in handling and finish…" This self-effacing assertion conceals the craft and level of detail inherent in Yellin's work.

Left: Detail of the handrail on the landing of the Boppard Room stairs, showing a particularly sinuous twist around a corner. Right: Detail of the tenon joining bracket and handrail on the Boppard Room stairs. Note the play of color and texture between the iron railing and Doria limestone wall.

Iron lacks intrinsic value as a material; it has little aesthetic appeal, the color is coarse, and it is often used for the most utilitarian items. Its singularly earthy appearance is one of the many reasons I think it so appropriate at The Cloisters, where it is nearly always seen against stone surfaces. Yellin's ironwork is endowed with a great deal of character and appeal based largely on the visual evidence of its having been crafted by hand. Yellin himself expressed the appeal of iron as a material: "I love iron: it is the stuff of which the frame of the earth is made and you can make it say anything you will."

All color photographs by Andrew Winslow