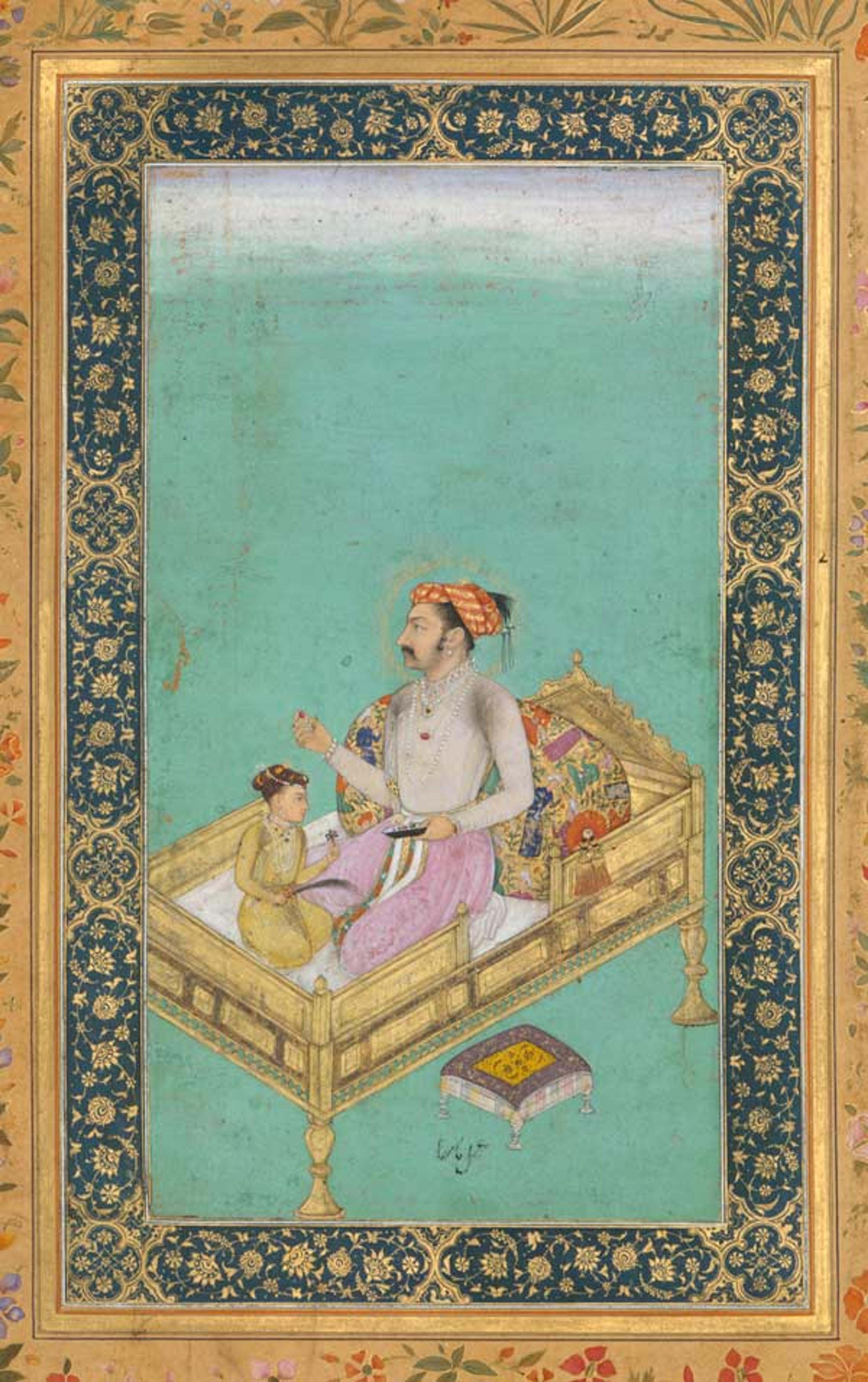

In this painting, the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan sits with his young son Dara Shikoh, holding a red gem in his right hand and a small tray of colored gems in his left. This intergenerational portrait illustrates the important Indian tradition of transferring gems among family members. Jewels are among the most important possessions in an estate and, when inherited, they are usually remounted or set by the recipient.

In the Indian tradition, gifting jewels can signify a rite of passage, or acknowledgement of an important life event. Take, for example, the jewelry used to indicate that a woman is married. Bangles, today worn by essentially all women in India, were historically reserved for women once they had tied the knot. The Al-Thani Collection boasts two pairs of stunning bangles. is from the late eighteenth century and enameled with bright red flowers on the inside and diamonds, pearls, and rubies on the outside.

The second pair, designed just three years ago by jeweler Viren Bhagat, maintains the traditional form but has a strikingly modern sensibility.

Pair of Bangles (kada) by Bhagat, 2012. India, Mumbai. Platinum, set with diamonds and pearls; Diam. 3 3/8 in. (8.6 cm). The Al-Thani Collection

Married women also traditionally wore a nath, or nose ring, in their left nostril.

Nose ring (nath), 1925–50. Western India. Gold, with diamonds, seed pearls, and rubies; H. 1 5/8 in. (4.2 cm), W. 1 1/2 in. (3.7 cm). The Al-Thani Collection

Other items of jewelry indicated a regal and political transition. A seal ring with an inscription (in reverse), for example, was created for a prince's ascension to power in south India.

Seal ring with hidden key, 1884–85. South India, Hyderabad. Gold, set with spinel; H. 1 1/8 in. (2.7 cm), W. 1 1/8 in. (2.8 cm); W. (with key extended) 2 1/8 in. (5.3 cm). The Al-Thani Collection

The prince in question, Mahbub 'Ali Khan Asaf Jah VI, ascended to the throne at the age of two in 1869, but he did not receive full authoritative powers until his eighteenth birthday in 1884. The inscription on this ring includes his date of becoming prince and his (very long) full title: "The Rustam of the Age, the Aristotle of the Time, Fath Jang Sipah Salar 1302 [1884–85] Muzaffar al-Mamalik Nizam al-Mulk Mir Mahbub 'Alikhan Bahadur Asaf Jah Nizam al-Dawlah." The key folds back to rest hidden beneath a hinged top—a secret of the wearer, who extended it only when he needed to open the mystery lock into which it fits.

Jighas, plume-shaped ornaments worn to decorate a turban, were also gifted to celebrate moments of transition or to reward particularly good service. This form of jewel has been used since the Mughal period and is fabricated from opulent gems and hardstones, and worn by courtiers, princes, and emperors.

Turban ornament (jigha), 1675–1725. North India or Deccan. Jade, inlaid with diamonds, rubies, and emeralds; with hanging pearl; H. 7 3/4 in. (19.6 cm), W. 1 3/4 in. (4.5 cm). The Al-Thani Collection

There is a recorded instance of a hardstone jigha being gifted by the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb to his general Shuja'at Khan in recognition of the suppression of an uprising in Afghanistan in 1673. A courtier surely would wear such a jewel proudly as a demonstration of his brave and loyal service.

As the Al-Thani Collection continues to reveal to us, a jewel is never just a jewel!