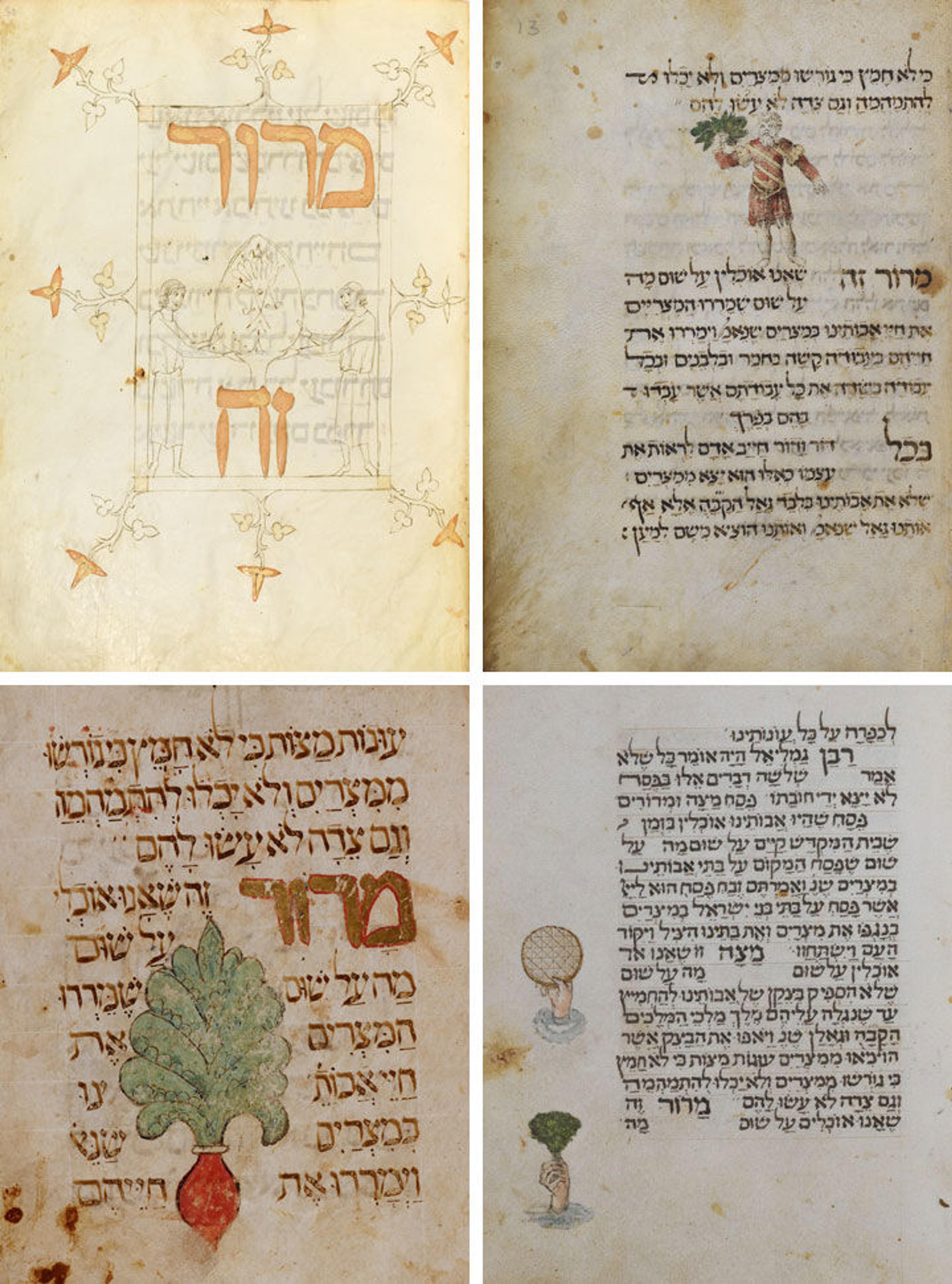

Clockwise from top left: Prato Haggadah, ca. 1300. Spanish. Tempera, gold, and ink on parchment. Courtesy of The Library of The Jewish Theological Seminary, New York (L.2016.6.25). Farissol Haggadah, 1515. Italian (Ferrara). Opaque watercolor and ink on parchment. Courtesy of The Library of The Jewish Theological Seminary, New York (L.2016.6.56). Gallico Siddur, 1487. Italian (Florence). Tempera and ink on parchment. Courtesy of The Library of The Jewish Theological Seminary, New York (L.2016.6.53). Graziano Haggadah, ca. 1300. Spanish. Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on parchment. Courtesy of The Library of The Jewish Theological Seminary, New York (L.2016.6.51)

«This selection of illuminated books offers a glimpse into the Passover feasts of medieval and Renaissance Jews in Spain and Italy, featuring lively depictions of matzah (unleavened bread) and maror (bitter herbs)—foods required for the Passover seder, the ritual meal that commemorates the exodus of the ancient Israelites from Egypt. The matzah refers to the unleavened bread the Israelites took with them as they left Egypt in haste, while the maror serves as a reminder of the bitter life of slavery that the Israelites had endured.»

The wide variety of vegetables shown as maror might seem surprising, especially since none is horseradish, which is used by many American Jews today. Medieval rabbis across Europe endorsed a host of bitter greens, including cardoon, horehound, endive, lettuce, and broccoli rabe. Only occasionally do medieval sources mention horseradish; Rabbi Alexander Suslin of Frankfurt, writing in the 14th century, suggested it could be a suitable alternative when lettuce was not available. Not until Jews migrated to the colder climates of Eastern Europe did its use become widespread in Ashkenazi communities.

As for matzah, we gain some sense of how it was made in earlier times from an unexpected source: testimony introduced by informers during the Spanish Inquisition in the 16th century. These documents offer a poignant record of the Passover preparations of Jews risking their very lives to practice their religion in secret. Most of the references to matzah making describe a simple dough of flour and water. The recipe outlined below, written by Beatriz de Díaz Laínez of Almazán and adapted from a 1505 court record, adopts a more inventive approach, adding wine and spice to this quintessential ritual food. Her story, like the manuscripts on display, shines a light on the culture, heritage, tenacity, and faithfulness of the Jews of medieval and Renaissance Europe.

- 2 cups flour, sifted

- 1/2 teaspoon black pepper

- Pinch of cloves

- 4 tablespoons honey

- 8 tablespoons white wine

- 4 egg yolks, beaten

- 4 tablespoons water

- Preheat oven to 400 degrees.

- Mix the flour, pepper, and cloves together in a small bowl.

- Combine the honey, white wine, and egg yolks. Add the mixture gradually to the flour and mix to form a very dry dough. Add the water slowly. You may not need all the water or you may need a bit more. Don't overmix.

- Form the dough into walnut-size balls. Roll them flat and thin on a floured surface. Prick them several times with a fork.

- Bake them on a nonstick cookie sheet for 10 minutes. You may have to use two cookie sheets.

- Remove them immediately from the cookie sheet and cool on a rack.

Makes about 12 matzahs.

This recipe is available in A Drizzle of Honey: The Lives and Recipes of Spain's Secret Jews, by David M. Gitlitz and Linda Kay Davidson (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1999).

The Prato Haggadah is on view at The Met Cloisters through August 11. The Gallico Siddur, Farissol Haggadah, and Graziano Haggadah are on view at The Met Fifth Avenue in gallery 306 through August 11.