Museum Seminar (MuSe) Internship Program cohort, 2018. Photo by Elizabeth Perkins

Summer is upon us, and for The Met, that means a new batch of summer interns has arrived. The staff in the Museum's Education Department do an incredible job of putting together a ten-week-long Museum Seminar (MuSe) Internship Program for college and graduate students to get practical experience in departments across the Museum. The arrival of this summer's interns is a special occasion for me, in particular, because it marks a full year since I started my journey here at The Met. I'm now a full-time employee of Watson Library, but I got my start here as a MuSe intern in the summer 2018 cohort.

The author on her first day as a MuSe intern. Photo by Ellen Faletti

The first Monday of June 2018 saw me and roughly thirty-five other interns, all from different backgrounds and with different interests, coming together for the first time. By the end of the summer, I had done and experienced things I never imagined. Not least among those experiences was the tour aspect of the internship. In addition to working in their assigned departments throughout the summer, each intern is also expected to design and give tours to the public. They are called Intern Insights tours, and they happen every Monday through Thursday from mid-June through mid-August.

It would be an understatement to say that I—someone with very little background in art history and no experience building or giving tours—was terrified of the process. (Spoiler: it's really not that bad, I promise.) Plenty of my fellow interns loved these tours and some people even realized through them that they have a passion for instruction. I think it's safe to say, though, that I was not the only one who was overwhelmed by the prospect.

In my cohort, there were people studying chemistry, public relations, library science (ahem), education, and media studies, to name a few. Art-historical research was not something that was familiar to all of us. Even with all of the resources that The Met and Watson Library have to offer, it was an intimidating process to do unfamiliar research and then present it to the public. I remember that my worst fear was that I would have a group who knew more about the objects I chose than I did. And sometimes that will happen, but it's not the end of the world.

Now, nearly a year later, I am much more familiar with Watson's resources and how to do art-historical and object-based research. I'd like to take my experience from the internship to hopefully rein in the terror that I know some incoming interns feel when faced with these tours. I hope by sharing the ways Watson Library and The Met's own website can make this research simpler, I am able to make the process a little less scary, not only for Museum interns, but also for anyone wanting to learn more about the history of art.

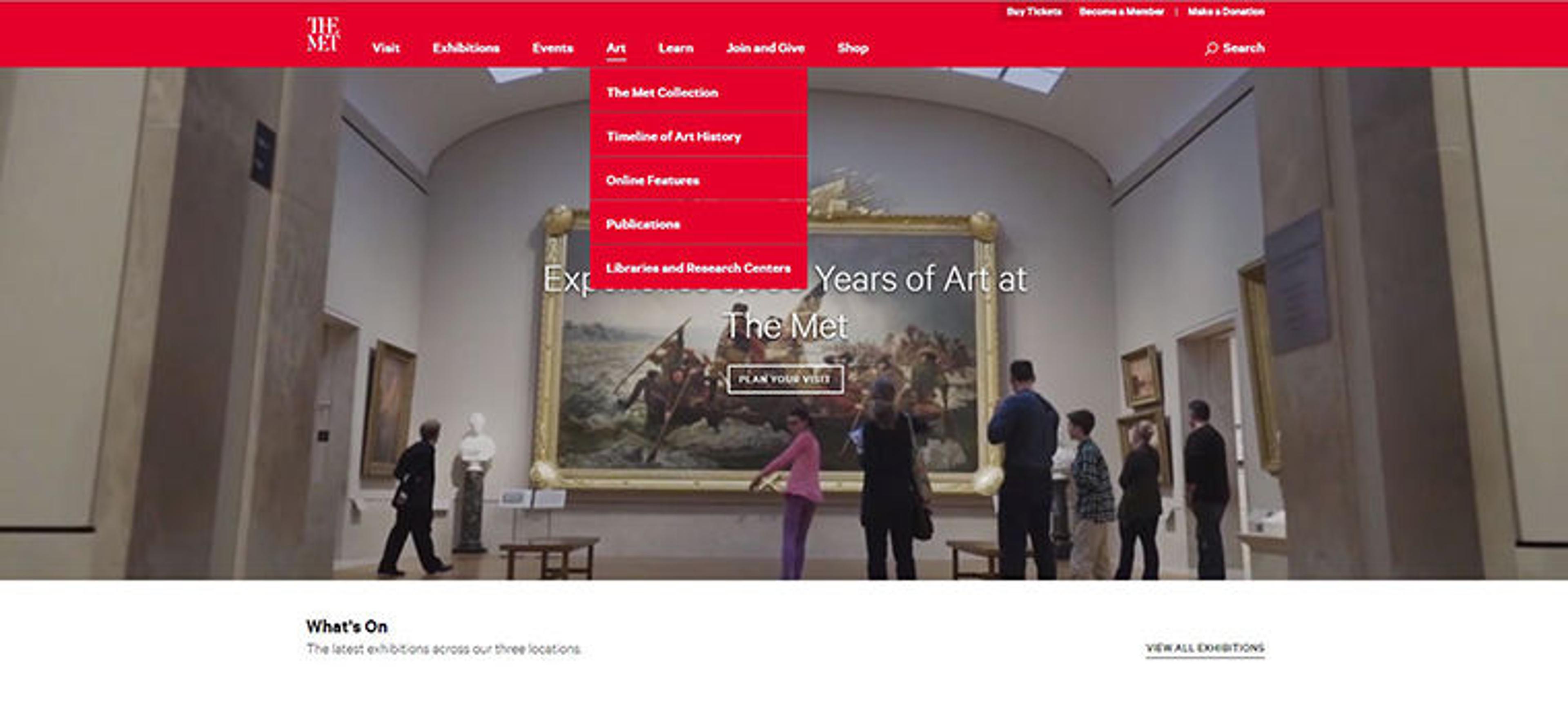

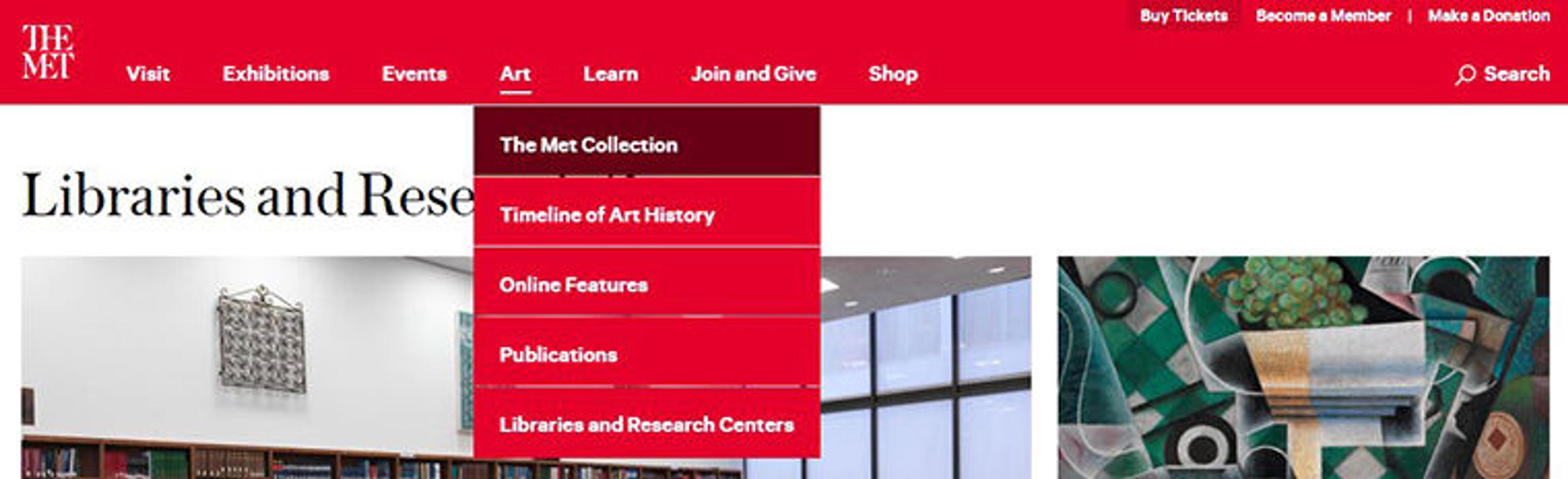

Unsurprisingly, the best place to start your object-based research is with the "Art" section at the top of The Met's homepage. Once you have selected an object that you want to research, you should navigate to "The Met Collection."

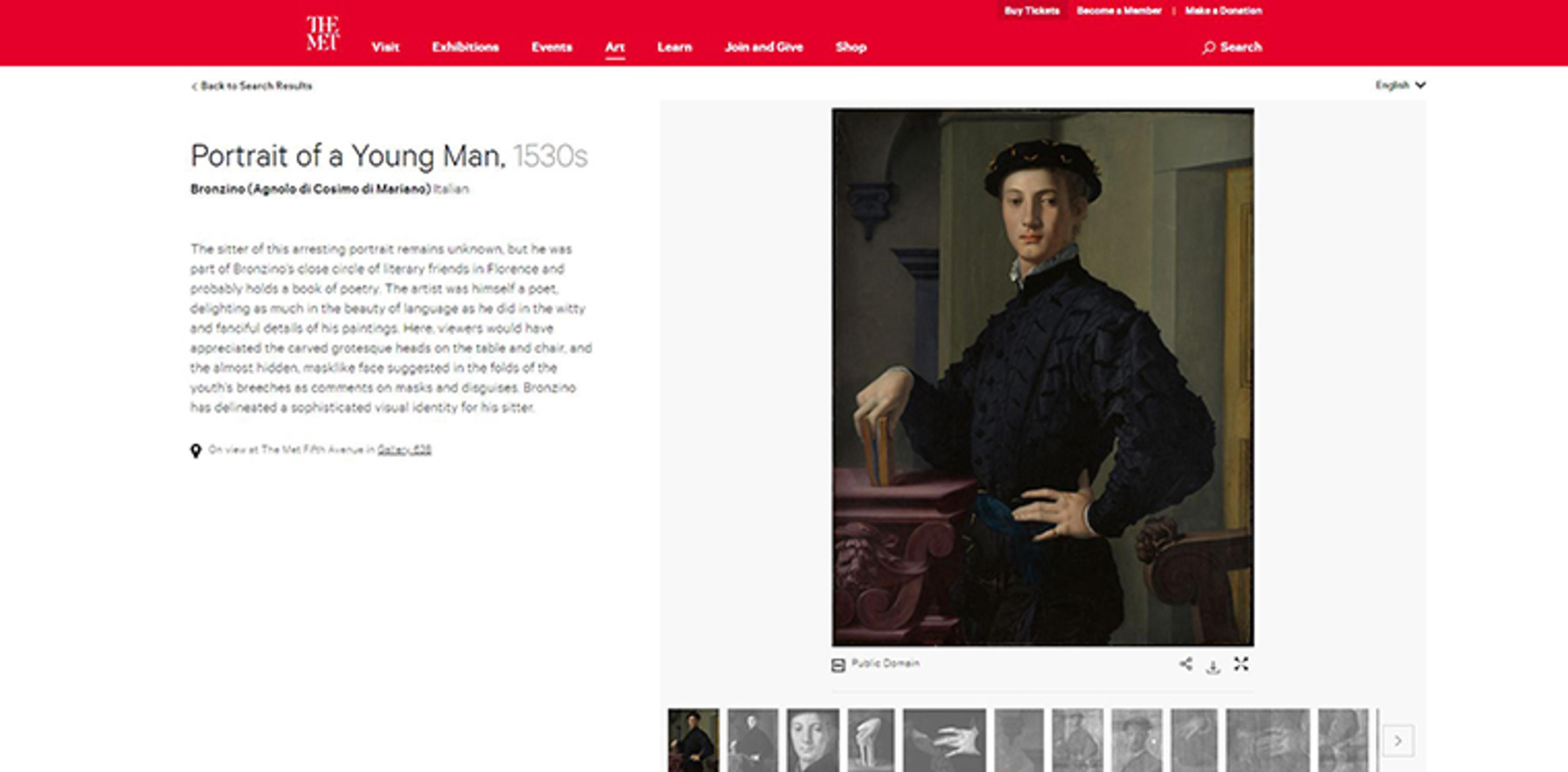

Here, you can search by title of an artwork, artist, region, time period, or accession number. If you already have a specific object in mind, the accession number is the best way to get directly to it. You can find an object's accession number by reading the wall text for the object in the galleries. Once you know the number, you can type it directly into the search box that appears on The Met collection online. For example, if you want to look for Bronzino's Portrait of a Young Man, you would type in "29.100.16." The painting you're looking for is the first result.

As seen above, there is (usually) a blurb about the artwork to the left of the image. The information there can be a great place to begin your research, but it is by no means the most helpful information on this page. Beneath the images are the "Object Details," which give basic information such as date or time period, medium, dimensions, and more. Particularly with objects for which not much is known, this information can be very valuable. If you feel like you've hit a dead end, you can look here to find keywords to broaden your search.

西漢 彩繪陶舞俑 Female Dancer, 2nd century B.C. China. Western Han dynasty (206 B.C.–A.D. 9). Earthenware with slip and pigment, 21 x 9 3/4 x 7 in. (53.3 x 24.8 x 17.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Charlotte C. and John C. Weber Collection, Gift of Charlotte C. and John C. Weber, 1992 (1992.165.19)

For example, if you are looking at this female dancer figurine, you can look at the object details to see that it originated in the Western Han dynasty and that it is considered tomb pottery. You could then search the library's collection for those terms, thus broadening the scope of your research.

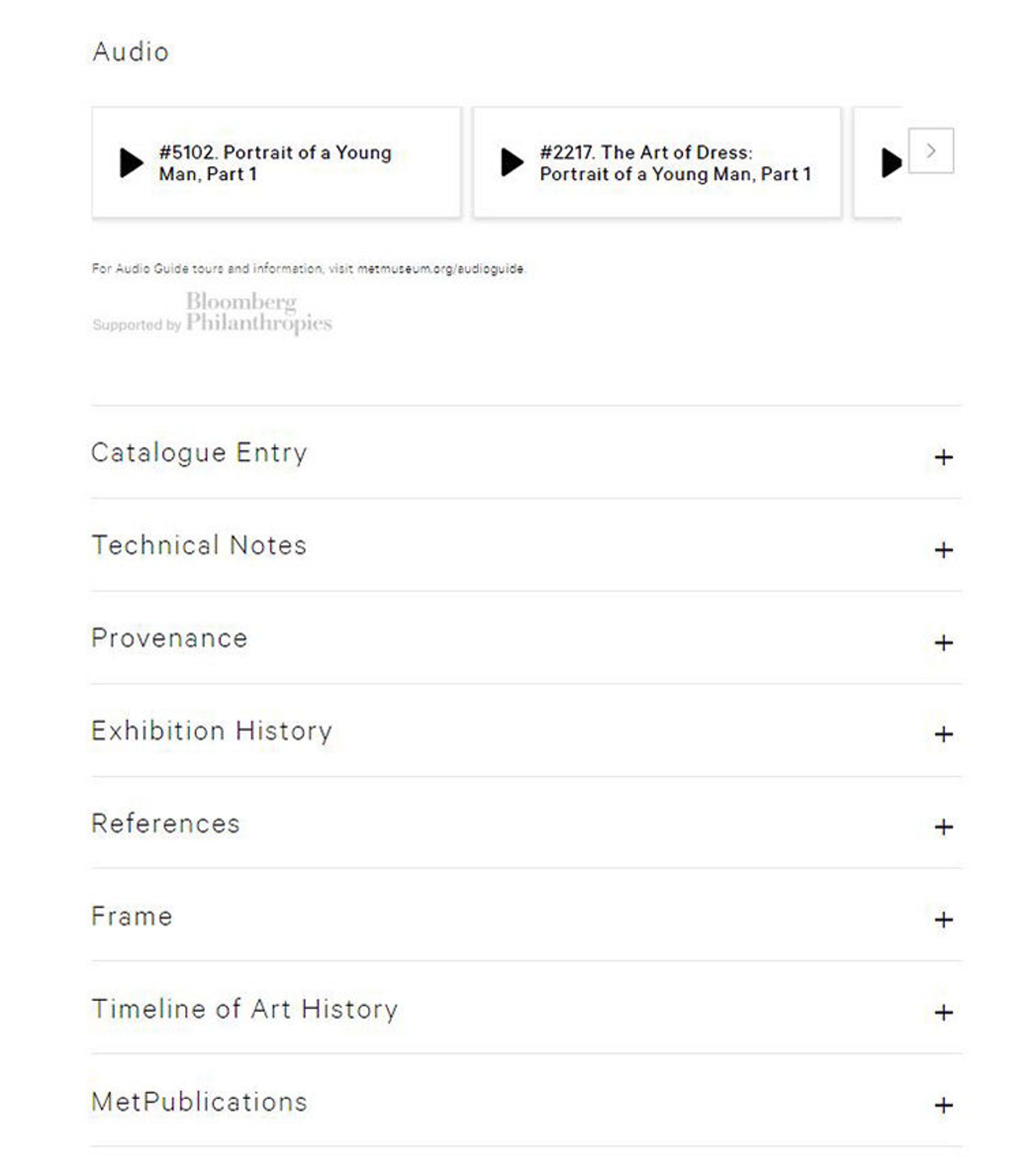

Beneath the object's details—or what we call its "tombstone" information—is further information on the object. The information about Portrait of a Young Man is extensive. Not every artwork in The Met collection will have so much information and scholarship attached to it. However, for nearly every artwork online, there is some information that can help you with your research. Information in each of the drawers can be valuable, depending on what you're looking for. The first place I usually turn when looking into an object is the "References" drawer. It's here that you will find citations for various sources that discuss the artwork.

From here, you do have to do some legwork and work backwards. You can search Watsonline, Watson Library's online catalog, for the title of anything that interests you. Be careful searching for journal articles, though. For those, you will have to search by the journal's title, then find the correct issue and go from there.

Two other drawers that often prove to be very useful are the Timeline of Art History and MetPublications. The Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History is an incredible resource that can help you contextualize and better understand your object. The Timeline is full of essays that relate to the object you are looking at, as well as historical information about the time period in which it was produced. MetPublications is where you can find many publications published by The Met. Some of these publications are available online, in full text, while others may just contain summaries and excerpts. The MetPublications drawer links directly to any publications that reference the artwork you are researching.

So much information about works in The Met collection can be found exclusively on The Met's website with just a little digging. In many cases, though, what is there may not be enough to fully flesh out a tour (or paper, presentation, or other reason for research). If you ever feel like you've hit a wall with your research, that's where we come in! The staff here in Watson are more than happy to help you with your research needs. It's literally our job, and we are glad to do it. I say that because I know how hard it can be to ask a stranger for help. Despite working in Watson all summer, I was still reluctant to go to my colleagues and ask for reference help with my tour because I did not want to seem like I didn't know what I was doing. Looking back, that seems ridiculous, but the fear was very real at the time. So learn from my mistakes and make the most of the resources the library has to offer you!

While there was probably nothing that would have completely eased my nerves regarding the tours I had to give, I feel pretty sure that I would have felt better about them if I had been more confident in my research. Speaking to the public is daunting. Speaking on a topic that you're largely unfamiliar with is also daunting. It's natural to be nervous. I ended up surviving my tours completely unscathed—you could probably even get me to say I enjoyed some of them. I can definitely say I learned more about the Museum, its collection, and visitors through the whole process, which is something I'm very happy about.