Read about how Tiffany & Co. employed the metalworking technique of electrolytic inlay with illustrative artworks and process demonstrations, or watch the video below.

Tiffany & Co. (American, 1837–present). Cup and saucer, ca. 1881. Silver, patinated copper, patinated copper-platinum-iron alloy, and gold, cup: 2 1/8 x 2 1/2 x 1 7/8 in. (5.4 x 6.4 x 4.8 cm); saucer: 1/2 x 4 in. (1.3 x 10.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Friends of the American Wing Fund and Emma and Jay A. Lewis Gift, 2016 (2016.688a, b)

Electrolytic Inlay describes a technique popular in the nineteenth century, in which a recess in a metal object could be plated or filled with another metal. This is achieved by submerging the object in an electrically conductive solution containing mobile metallic ions, also known as an electrolyte, and applying electricity in the form of direct current. This process is closely related to electrolytic etching, where direct current is used to etch or create a recess in the surface of a metal object. In the nineteenth century at Tiffany & Co. and other firms, the two techniques were often used in conjunction with one another. They would create a recess in a metal object in one solution, then inlay a different metal by submerging it into a second solution.

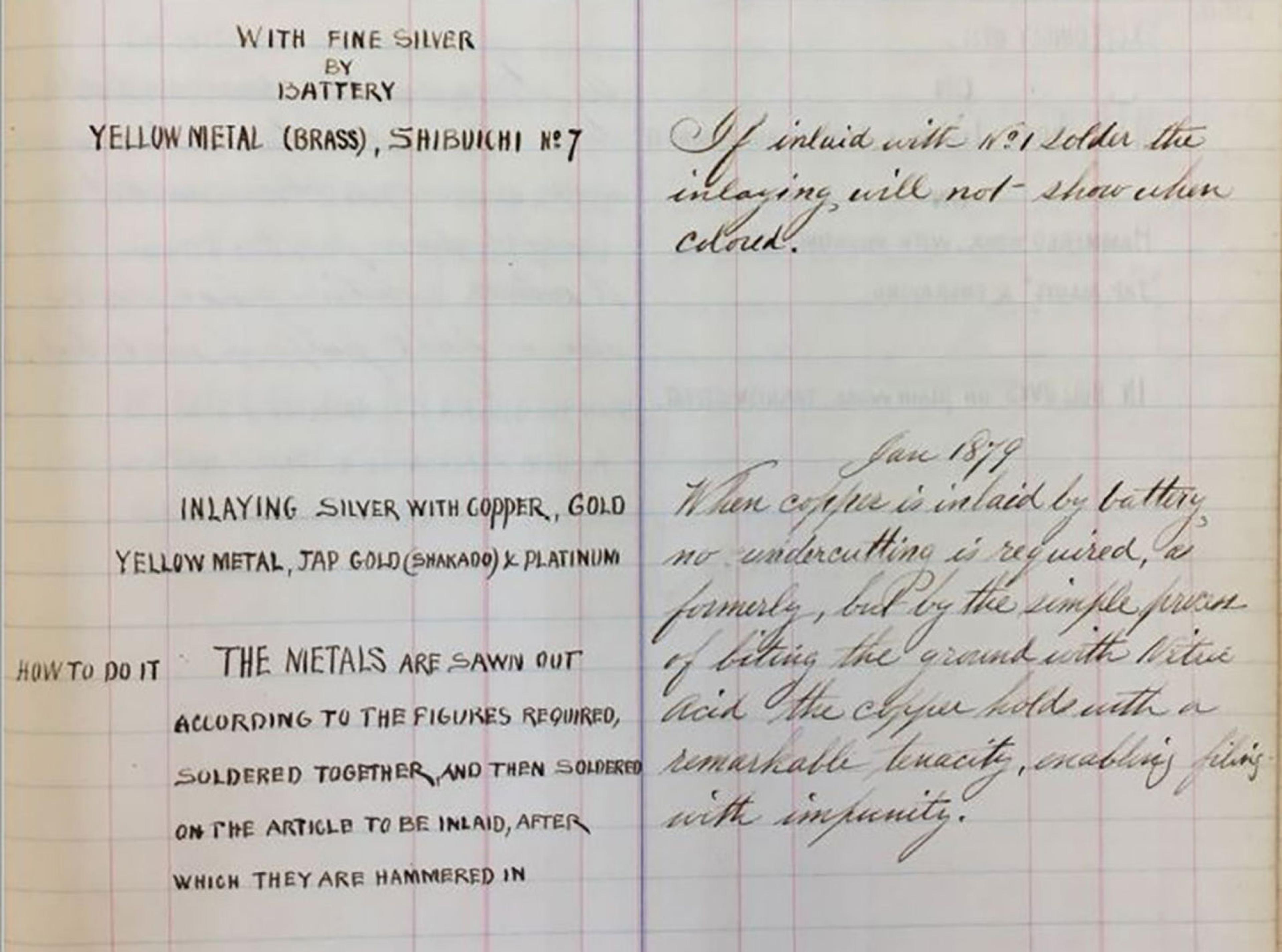

Tiffany & Co., Technical Manual (detail). Gorham Company Archive, John Hay Library, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island

“When copper is inlaid by battery no undercutting is required, as formerly, but by the simple process of biting the ground with Nitric Acid the copper holds with a remarkable tenacity, enabling filing with impunity.”

— Excerpt from a Tiffany & Co. nineteenth-century silversmithing technical manual.

By employing these electrolytic techniques, nineteenth century craftspeople were able to create complex mixed metal objects economically and efficiently. Many times, a combination of techniques would be employed on a single object: some inlays would be “applied by battery,” and others would be hammered. The characteristics of the design and the quality of the material to be inlaid influenced which process the craftspeople chose to employ. Experimentation allowed them to determine what yielded the most attractive and cost-effective results.

Select elements on these objects were electrolytically inlaid. Left: Tiffany & Co. (American, 1837–present). Vase (detail), 1879. Silver, copper, gold, and silver-copper-zinc alloy, 11 1/2 x 6 3/8 in. (29.2 x 16.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Sansbury-Mills Fund, 2019 (2019.44) | Right: Tiffany & Co. (American, 1837–present). Chocolate Pot (detail), 1879. Silver, patinated copper, gold, and ivory, 11 5/8 x 7 x 5 1/2 in. (29.5 x 17.8 x 14 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Louis and Virginia Clemente Foundation Inc. and Emma and Jay A. Lewis Gifts, 2017 (2017.156a, b)

To create an electrolytic inlay, the surface of the object being inlayed must be cleaned to remove any fingerprints or grime. A recess for the inlay needs to be created in the object. This can be done mechanically (by removing metal from the surface with tools), by acid etching, or via electrolytic etching. In the example below, the letter M has been electrolytically etched into the surface. A resist is applied over the rest of the surface to help prevent copper ions in the electrolytic solution from plating onto the surface outside the etched M.

The silver coupon, or small piece of metal, is suspended in the electrolytic solution copper sulfate, along with a second square coupon made from copper. Both coupons are connected to a direct current source—an instrument called a rectifier—which is used to convert alternating current from a wall socket into direct current. This device allows the operator to control the direction of the electricity. The silver coupon acts as the negatively charged cathode, and the copper coupon acts as the positively charged anode. When the current is applied, the cathode gains electrons and becomes negatively charged, leading the positively charged copper ions in the copper sulphate solution to migrate to the silver and deposit in the recess of the M. It takes hours to build up a thick layer.

After the copper ions have successfully filled the M, the two coupons are detached from the current source and removed from the solution. Any copper that has plated outside the recess is then removed, and the surface is cleaned and polished. This process is generally referred to as finishing. As part of this process, any dendrites that may have formed on the surface are clipped off with pliers or reduced with a file. Dendrites are the branching copper formations that can be seen below on the surface of the silver coupon. A finer file or stone is used to remove the resist and reduce any remaining plating outside of the intended area while polishing the silver and copper surfaces.

Any slurry and residue from the stone are rinsed and wiped off, revealing the copper inlay filling the recess.