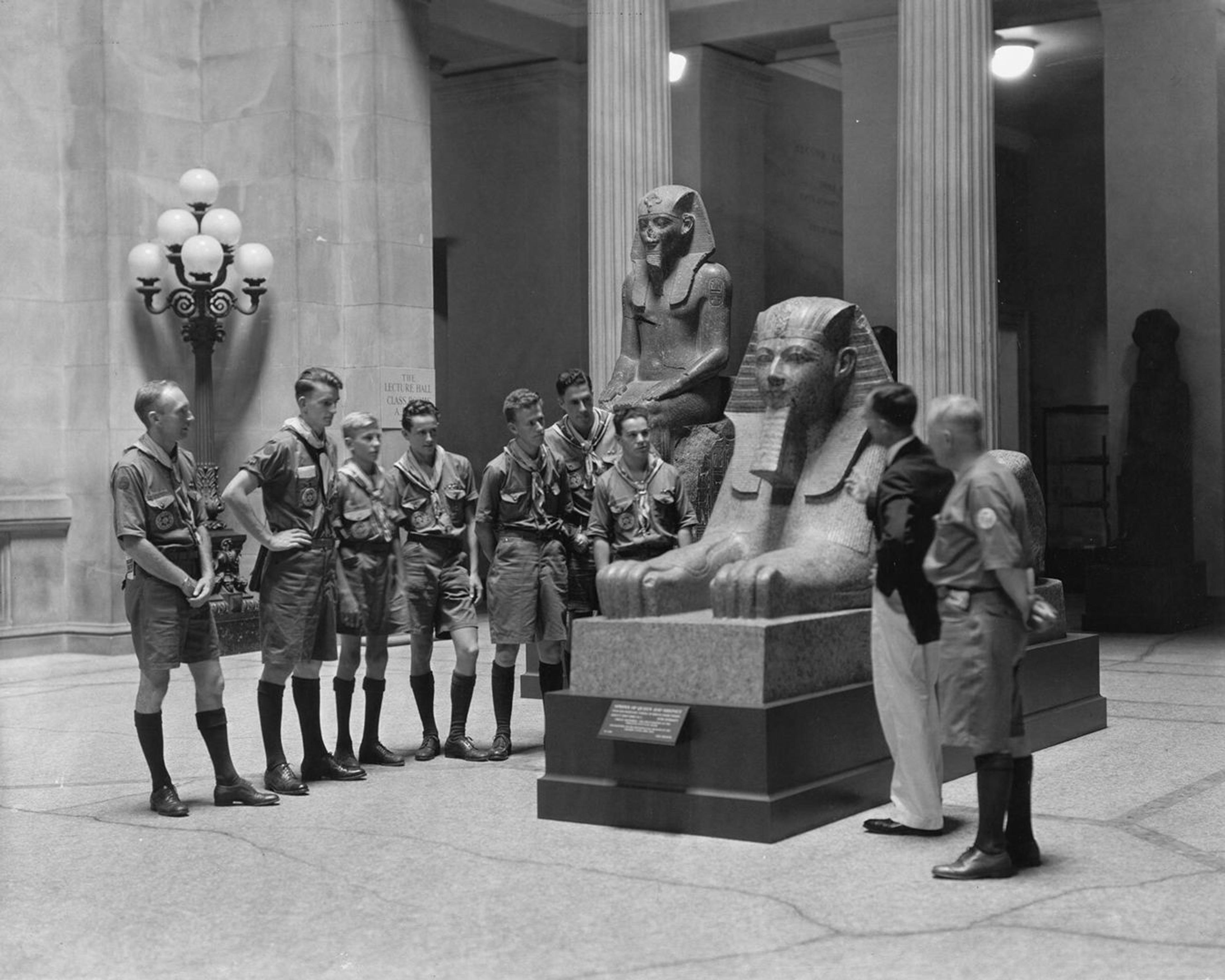

A troop of Boy Scouts from California visits the Museum on August 20, 1935.

Following The Met’s temporary closure in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, staff began researching how the Museum had responded to other global crises that took place during its 150-year history. Staggering unemployment figures and the bleak economic outlook for 2020 and beyond soon invited immediate comparisons with the Great Depression of the 1930s, when The Met faced the most difficult fiscal challenge in its history. In April 1932, the Director of the Museum, Herbert Winlock, reported that a “very serious financial situation is presenting itself to us and stringent economies will have to be put into effect immediately.” Winlock implemented such cost-saving measures as a freeze on new hiring, pay cuts, reductions in building maintenance, and curtailment of object photography. Attendance at The Met Fifth Avenue declined from just under 1.3 million visitors in 1930 to 886,000 a decade later.

Remarkably, however, this was also a time when The Met launched bold, innovative new programs to engage and inspire the public. Perhaps the most notable accomplishment of the 1930s was the design, construction, installation, and opening of the Cloisters. The Met’s first branch location was conceived in the 1920s as a museum dedicated to European medieval art, but ground was not broken in today’s Fort Tryon Park until 1934. The massive effort, which included a reconfiguration of the surrounding landscape as well as the construction of a new building, was a source of much-needed income for the many laborers it employed. Financier and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr. funded the project, gave millions of dollars to purchase works for its galleries, and established an endowment that continues to support acquisitions today. The Cloisters opened to the public on May 10, 1938, providing a beautiful new venue for art appreciation, learning, and inspiration as the nation continued to struggle through the last years of the Great Depression.

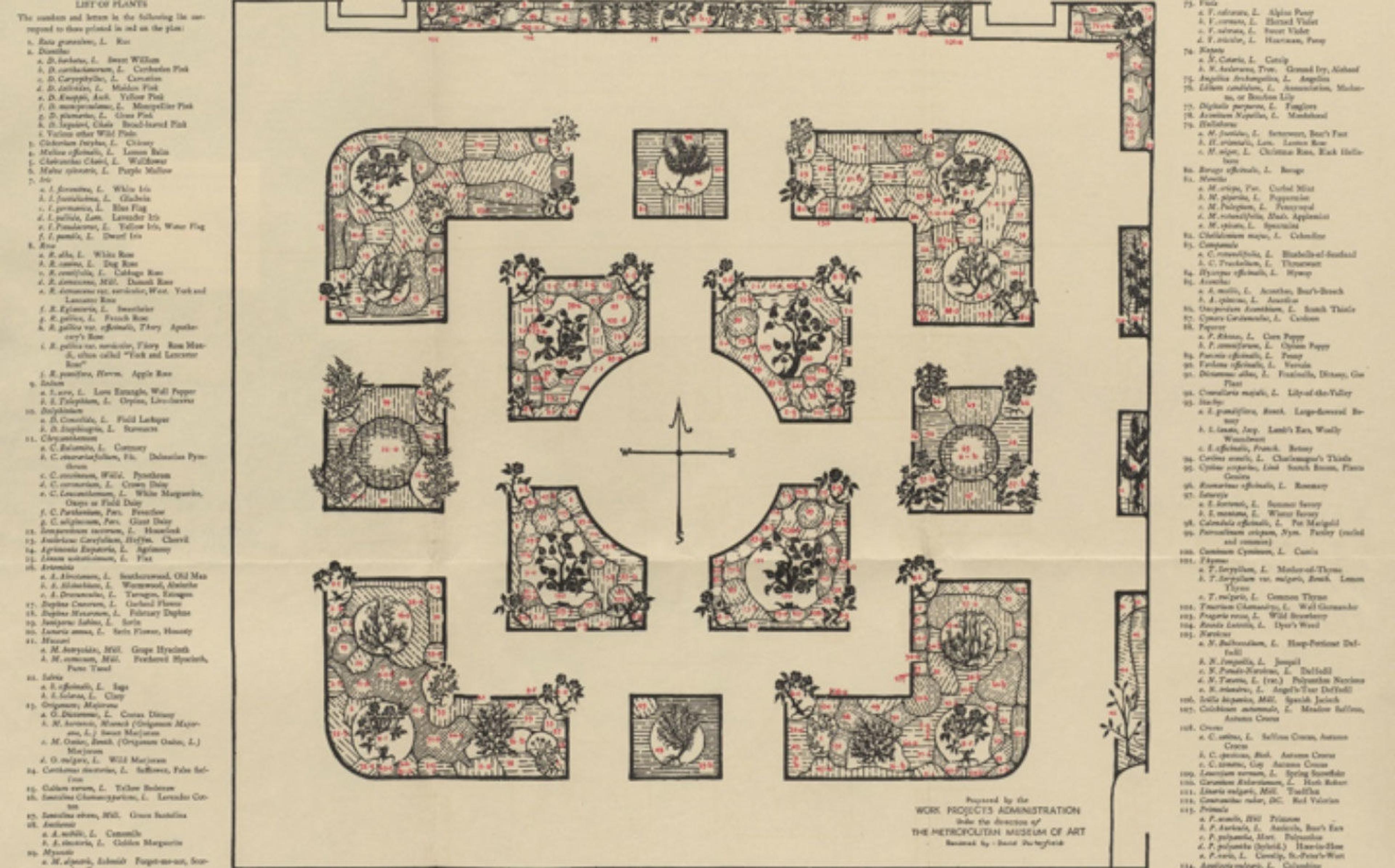

"Plan for the Garden in the Bonnefont Cloister," prepared by the Works Progress Administration for The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1941

Another impressive achievement of the 1930s was the publication of a revised and expanded edition of the Museum’s Guide to the Collections. Acknowledging that “the Museum has become too vast for a single visit,” the new guide appeared in two volumes from 1934 to 1935. While earlier versions were mostly text and led visitors along a linear path following the floorplan of the building, the new guide was arranged thematically and introduced collection highlights in a copiously illustrated handbook format. “A page for every gallery and a picture on every page,” announced The Met proudly, “this is the scheme that makes the new Guide to the Collections . . . the indispensable companion for travelers in the Museum.”

As The Met sought to inspire audiences struggling through the Depression, it relied on the support of the federal government, notably through the Works Progress Administration (WPA, renamed the Work Projects Administration in 1939), a New Deal government agency that employed millions of Americans who carried out public works and community service projects. While many WPA workers built roads, bridges, and other infrastructure, some of its divisions assigned people to work in arts, culture, and community service organizations, including museums. Several dozen WPA staff served at The Met from 1934 to 1942. They prepared maps and charts on art historical themes for classroom and gallery instruction, photographed and illustrated Museum objects for use in publications, guarded Museum objects, presented lectures, installed exhibitions, and conserved the Museum's cast collection.

"European Textiles and Costume Figures," with students and a teacher from Hunter College’s new Bronx campus, Walton High School, 2780 Reservoir Avenue, The Bronx, 1939

WPA workers also supported a unique Met initiative of the Great Depression known as Neighborhood Circulating Exhibitions. A series of ten thematic installations comprising artworks from the Museum’s collection traveled to public libraries, community centers, schools, and municipal buildings across New York City. More than two million people viewed these exhibitions, which featured Egyptian and Greek antiquities, arms and armor, Japanese and Chinese art, and textiles from around the world. A recently opened special exhibition in the Ratti Textile Center, Art for the Community, on view through June 13, 2021, highlights this important effort to present Met objects in public spaces outside the Museum’s walls.

In the early 1940s, as the United States entered World War II and national unemployment numbers decreased, WPA initiatives gradually ceased operations, and the WPA was officially terminated in 1943. Artworks produced for the WPA’s Federal Art Project (WPA-FAP), a New Deal program established to employ artists, made their way to The Met, including drawings made under the aegis of the Index of American Design. The Index was the brainchild of textile designer Ruth Reeves and Romana Javitz, head of the Picture Collection at the New York Public Library. Reeves and Javitz identified a need on the part of artists and designers for more readily available archives of visual material relating to the arts of the United States—an area in which the NYPL’s Picture Collection was lacking—and successfully petitioned to establish a government-sponsored program in response. WPA-supported artists across the country visited art museums (including The Met), historical societies, commercial galleries, antique shops, and collectors’ homes to create meticulous watercolor renderings of American vernacular objects ranging from weathervanes to textiles to stoneware. The project resulted in the production of over 18,000 drawings.

The Index was sent to The Met in May 1942 but, because the drawings were the property of the United States government, a formal agreement was reached just a year later to transfer it to the National Gallery of Art. In 1944, the holdings were shipped from New York to Washington, D.C. During its brief stewardship of the Index, and under the supervision of the Index’s national coordinator Benjamin Knotts, the Museum organized numerous thematic exhibitions of Index drawings at The Met Fifth Avenue as well as shows that traveled to institutions across the country. An example is “Emblems of Unity and Freedom,” which showcased Index drawings of textiles, pottery, figureheads, and other objects of the eighteenth and nineteenth century that feature symbols associated with the United States, including flags, eagles, and the Liberty Bell. In his review of the Yale Art Gallery’s iteration of the exhibition, Gy Blas of the New Haven Register commented that many of the drawings could be considered “little masterpieces” and lauded their “detailed technical accuracy.” Writing in 1943, Blas observed: “It is especially important in this period of turmoil to acquaint ourselves with such traditional material, trace its sources in the life of the people and know better the symbols created to keep alive the historic meanings of democracy.” In addition to organizing exhibitions, The Met established an Index Study Room where members of the public could view material not on display, published several thematic catalogues, and issued Christmas cards featuring drawings from the Index.

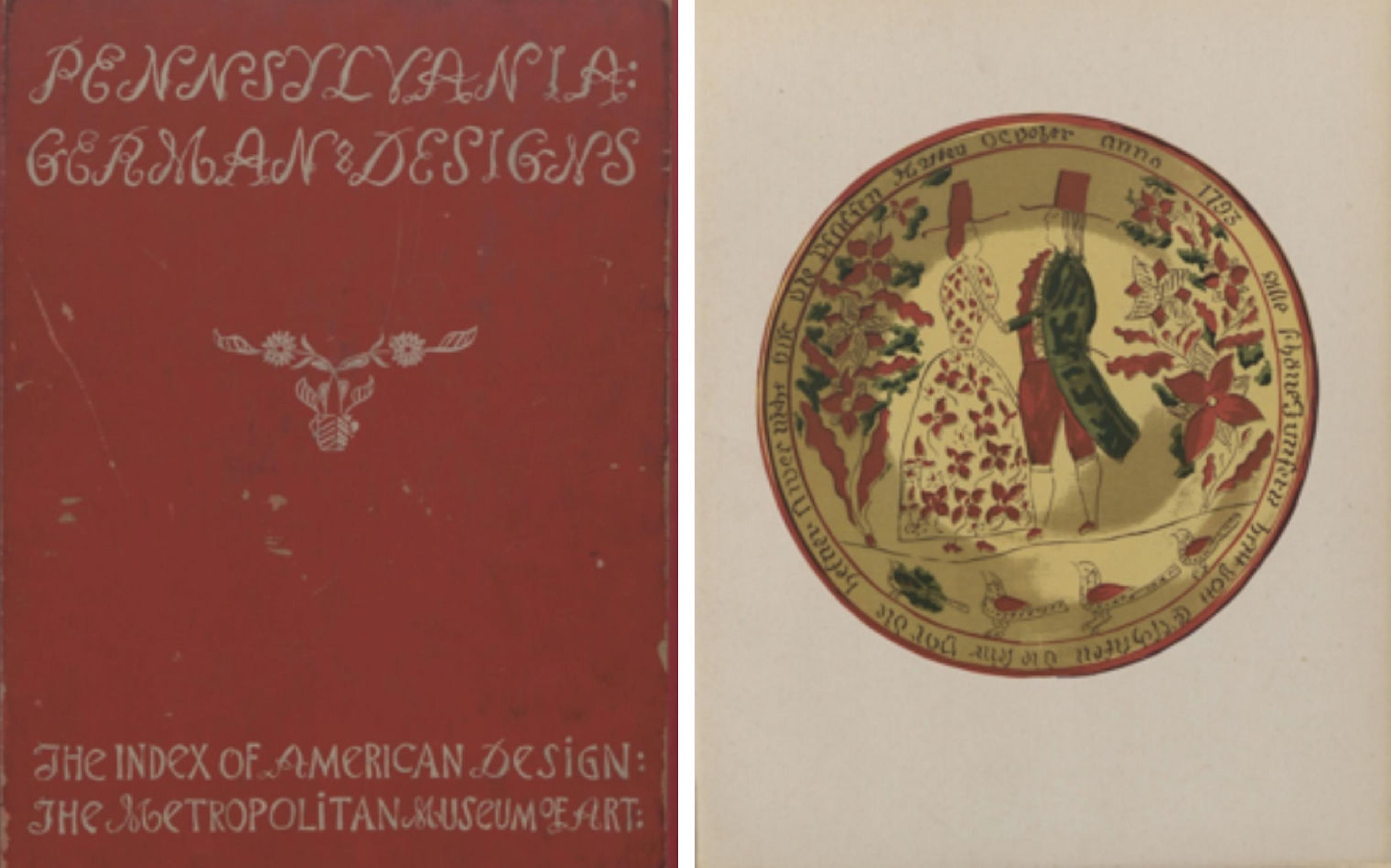

Cover and Plate 8 from Benjamin Knotts, Pennsylvania German Designs: A Portfolio of Screen Prints(New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1943)

One such publication, Pennsylvania German Designs: A Portfolio of Screen Prints (1943), reproduced in screenprint twenty Index drawings of earthenware plates, pine chests, and other historic design objects made by craftspeople of German descent from the Pennsylvania region. As Knotts noted in the catalogue’s introduction, screenprint had “been used for several decades for many industrial purposes” and had “spread beyond its original use and development in display, poster, and textile manufacture to other fields and is now widely used by artists in producing limited editions of fine prints.” In fact, screenprint had enjoyed a recent rise in popularity among artists due in part to the opening of screenprint facilities under the auspices of the WPA-FAP. The printers responsible for executing the plates in Pennsylvania German Designs were members of the Creative Printing Group, a press operated by artists formerly employed by the New York City unit of the WPA.

In addition to housing the Index of American Design for roughly two years following its dissolution, The Met acquired a collection of over 1,700 fine art prints in 1943, when the federal government distributed hundreds of thousands of prints produced within the printshops of the Graphic Arts Division of the WPA-FAP to tax-supported institutions across the United States. A press release issued by the Museum on October 19, 1943 announced the exhibition of a selection of 129 prints from the gift, stating, “the collection of WPA prints, a gift of unique importance, makes available to the public a cross-section of contemporary graphic art in this country.” Printmaking had flourished in the United States during the prior decade thanks to the WPA, which provided artists with access to printmaking tools, equipment, and materials that were otherwise often difficult to come by.

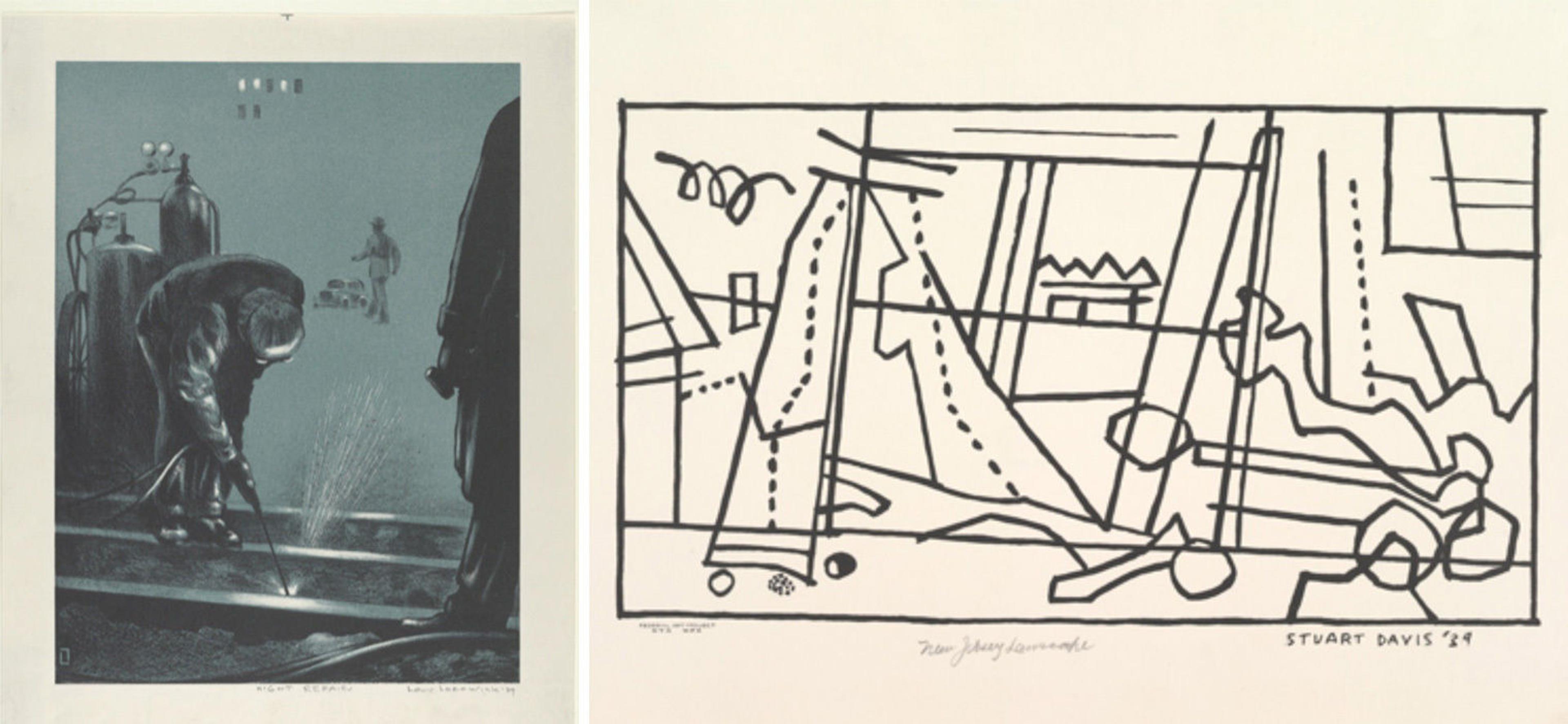

Left: Louis Lozowick, Night Repairs, 1939, color lithograph, Gift of the Work Projects Administration, New York, 1943 (43.33.1181). Right: Stuart Davis, New Jersey Landscape, 1935–43, lithograph, Gift of the Work Projects Administration, New York, 1943 (43.33.1026)

Certain WPA-FAP printshops and community art centers offered printmaking instruction, and many gave artists free rein to operate printing presses. This tendency resulted in a shift away from tradition, whereby an artist conceived of a composition and a master printer with specialized training in etching, engraving, or lithography was responsible for printing it. The unprecedented access that the WPA provided to artists led to the blurring of boundaries between artist and master printer, and artists were given relative freedom to experiment with a broad range of subjects, styles, and techniques in their work.

The Met’s collection of WPA prints attests to the technical advancements in printmaking that were achieved in WPA-FAP Graphic Arts Division workshops across the country. In addition to the transformation of screenprint from a technique largely relegated to commercial printing into one taken up by artists, printmakers also made strides in lithography. In fact, the exploration of color lithography, which requires the use of a separate lithographic stone for the application of each color, was the impetus behind forming New York’s WPA-FAP Graphic Arts Division workshop. The New York-based workshop became a hub for the City’s vibrant community of politically engaged artists, many of whom took up social justice themes in their work. Artists such as Harry Gottlieb, Louis Lozowick, Elizabeth Olds, and Harry Sternberg embraced printmaking for its ability to yield large edition sizes, enabling the wide circulation of their social realist images. Others, including Stuart Davis, welcomed the opportunity to apply experiments in abstraction to the medium of print.

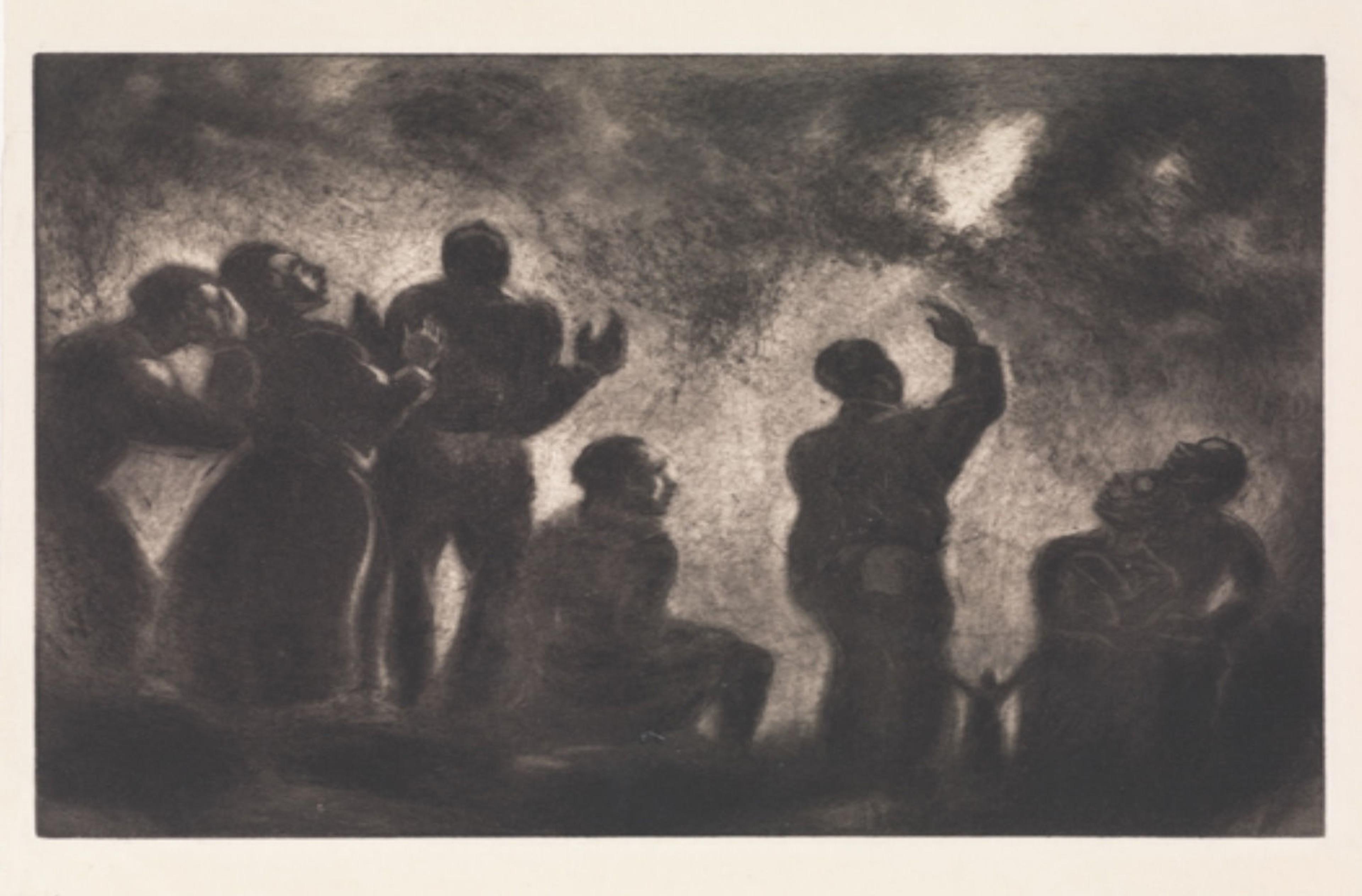

Dox Thrash, Glory Be, ca. 1938-43, carborundum mezzotint, aquatint, and etching, Gift of Reba and Dave Williams, 1999 (1999.529.162)

Decades later, in 1999, collectors Reba and Dave Williams donated two hundred prints to The Met by Black printmakers active between the late-1920s and mid-1940s, including a substantial number of prints produced in WPA workshops. The Williams’ gift greatly enhanced the Museum’s existing holdings of WPA prints, filling a gap in the collection with many rare works. Included in the gift are works by Dox Thrash, who co-created carborundum printmaking, a wholly new technique that produces rich, velvety tones, at the Fine Print Workshop of the WPA-FAP in Philadelphia. With the addition of the Williams’ gift, The Met collection now presents a comprehensive history of the technical advancements made in WPA-FAP print workshops. The gift also illustrates The Met’s earlier efforts to expand its collection of works by artists of color—an objective that was recently reiterated and memorialized in “Our Commitments to Anti-Racism, Diversity, and a Stronger Community” that the Museum released on July 6, 2020. These artworks, like the Cloisters building or the textile samples once displayed in Neighborhood Circulating Exhibitions, form a link with the Great Depression and symbolize how The Met responded creatively to global crisis in an earlier time.