The Metropolitan Museum of Art decorated as the official reviewing stand for the parade honoring the homecoming of the 27th Infantry Division from World War I, March 25, 1919.

On March 13, 2020, just one month shy of its 150th anniversary, The Metropolitan Museum of Art closed to the public for what would become an unprecedented period of over five months. As COVID-19 incited a state of crisis in New York City and the world at large, the Museum pivoted to ensure the safety of its community, collections, and buildings and to make the most of digital media to connect worldwide audiences, then sheltering in place, with art and educational resources. In previous times of crisis, The Met had never been forced to shut its doors for more than a few days and could offer respite to visitors in its galleries. The new challenges of 2020 were met with new opportunities through technology and social media.

At the same time, the historic nature of the pandemic stimulated interest in past precedents. Our exhibition Making The Met, 1870–2020 and its corresponding catalogue were conceived to present the history of the Museum through ten episodes in which the collections and ambitions of the institution transformed in response to societal shifts and visionary figures. It dawned on those of us working on the show, which was originally slated to open at the end of March, that we had found ourselves in an eleventh pivotal moment, one that continues to evolve in tandem with the world around us.

Inquiries began to stream in about the historical context for the closure and pandemic. Had the Museum ever closed for more than a week? (Not since 1879–80 when it relocated from its second temporary location on 14th Street to its permanent home at 82nd and Fifth Avenue.) How had The Met reacted to the 1918 flu epidemic? (Apparently minimally since the topic escaped mention in Museum publications, histories, or press of the time.) Out of the general interest in institutional history arose this blog series, which offers new insights into previous moments of crisis and reckoning that resonate with the events of 2020. Like the stories in Making The Met, they are told through multiple voices and highlight significant institutional initiatives and the experiences of individuals.

1918: A Year of War

“This has been a year of war. The interest of the American people has been centered on war and war activities. The educational interests of the country, of which the Museum forms part, have been absorbed in war…. Even the Museum, in its Department of Arms and Armor, has become something of an annex to the War department.” [1]

So concluded the Trustees' report on the landmark year 1918, the first featured moment in this series. Although that date initially came to mind because of the deadly flu pandemic, the turbulent circumstances of the war and its widespread reverberations through society seem to have had a more immediate effect on the Museum. Attendance, memberships, and city funding decreased, and according to the New York Times, “This year, the one before the Museum will celebrate its golden jubilee, it announces itself the poorest it has been in funds for its running expenses.” [2]

City Health Commissioner Royal S. Copeland prioritized keeping educational institutions—not only schools but also theaters and museums—open during the flu outbreak. The Met’s year-end report emphasized that, in spite of decreased attendance, there were more visitors who “came with a purpose” to lectures, children’s story hours and class trips, study rooms, the library, and copying sessions, highlighting the impact of its educational programs. In the galleries, the “princely” collections of J. Pierpont Morgan, one of the most magnificent bequests in the Museum’s history, and Mr. and Mrs. Isaac D. Fletcher were unveiled, along with a new section devoted to Indian art.

Left: Marsden Hartley (American, 1877–1943). Portrait of a German Officer, 1914. Oil on canvas, 68 1/4 x 41 3/8 in. (173.4 x 105.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949 (49.70.42)

At the same time, artists were capturing the spirit of the moment, and many of their works are now part of The Met collection. Among them, Marsden Hartley’s iconic Portrait of a German Officer of 1914 pays tribute to Prussian lieutenant Karl von Freyburg, whom Hartley loved and was killed in the war. Photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz acquired the painting from the artist, and it entered The Met in his bequest in 1949, which laid foundations for the Museum’s collection of modern art.

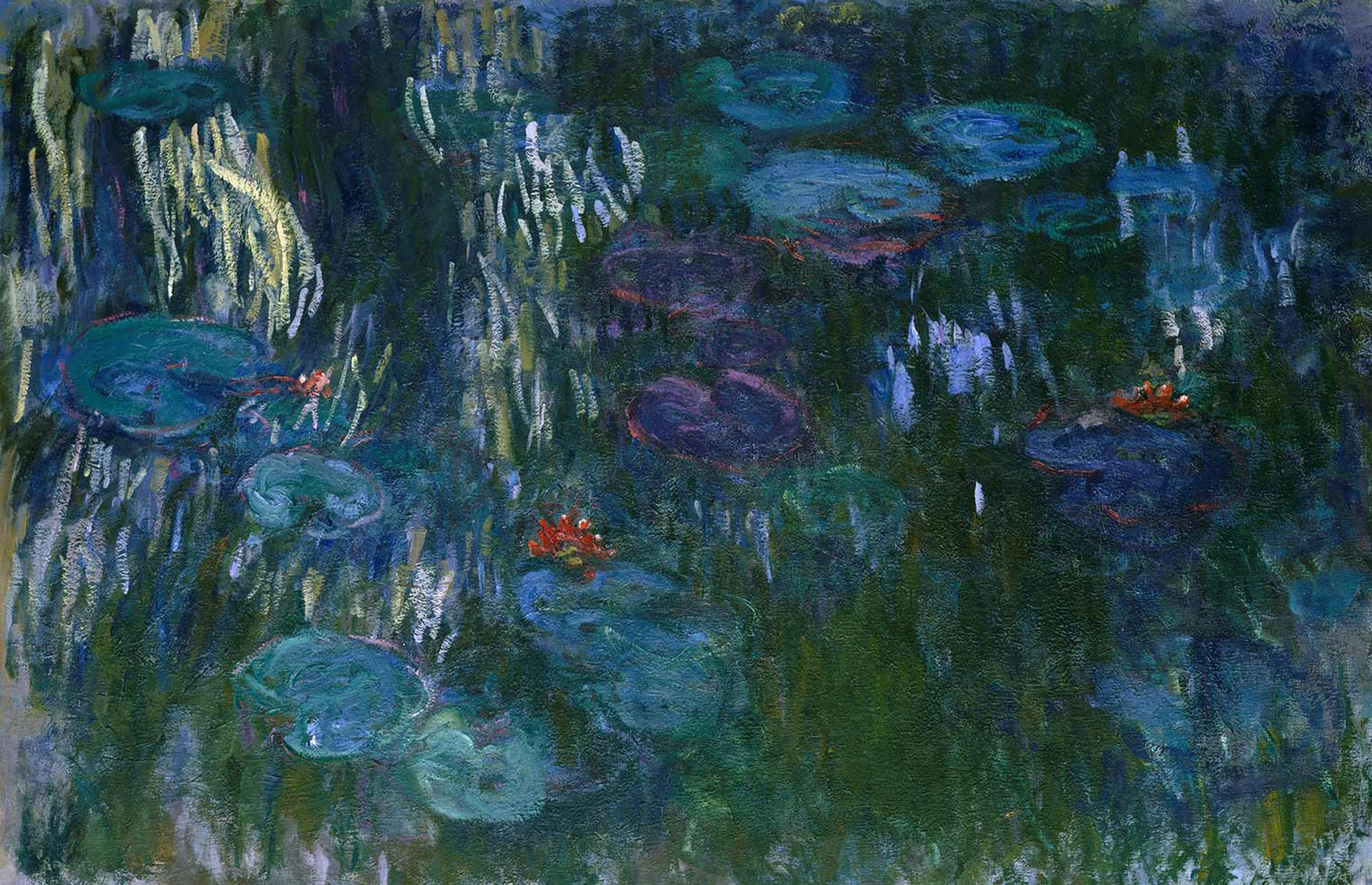

Perhaps less readily apparent but no less poignant, Claude Monet’s famous series of water lilies represents his response to the war. After a period of inactivity, the Impressionist picked up his brushes again near the end of 1914: “It’s the best way to avoid thinking of these sad times. All the same, I feel ashamed to think about my little researches into form and color while so many people are suffering and dying for us.” [3]

The war hit Monet close to home—quite literally, with battlegrounds in earshot of his otherwise serene garden at Giverny and both his son and stepson deployed into service. He began to create monumental, immersive canvases on which he rendered the reflective surfaces of his water lily pond in bold, gestural brushwork, infinitely expansive with no indication of horizon or shoreline. The Met’s Water Lilies of 1916–19 is one of the more complete compositions, with a deep, moody palette punctuated by lighter vertical strokes suggesting the reflection of weeping willows, symbols of mourning.

Claude Monet (French, 1840–1926). Water Lilies, 1916–19. Oil on canvas, 51 1/4 x 79 in. (130.2 x 200.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Louise Reinhardt Smith, 1983 (1983.532)

On November 12, 1918, the day after armistice, Monet wrote to politician Georges Clemenceau to offer two of these paintings to the French state as a monument to peace. In its final form, the gift took shape as a cycle of canvases encircling two oval rooms at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris. At The Met, Water Lilies (and another painting from the series on loan to the Museum) anchor Gallery 819, a space that has long been a source of solace and reflection, never more relevant than in these recent months of 2020 when we could appreciate the galleries anew after the Museum’s closure and in the midst of our own period of global crisis.

The Met at War: Stanley J. Rowland and Bashford Dean

When the United States entered World War I in April of 1917, The Met and many of its staff members quickly became involved in the war effort in various ways, including fund drives, making supplies to send to soldiers, and offering special guided tours to servicemen. Thirty-three Met employees, about ten percent of the staff, served in the war. Most joined the American Expeditionary Forces, but several others, those who were citizens of France, Germany, and Great Britain, returned home or served their countries in other parts of the world.

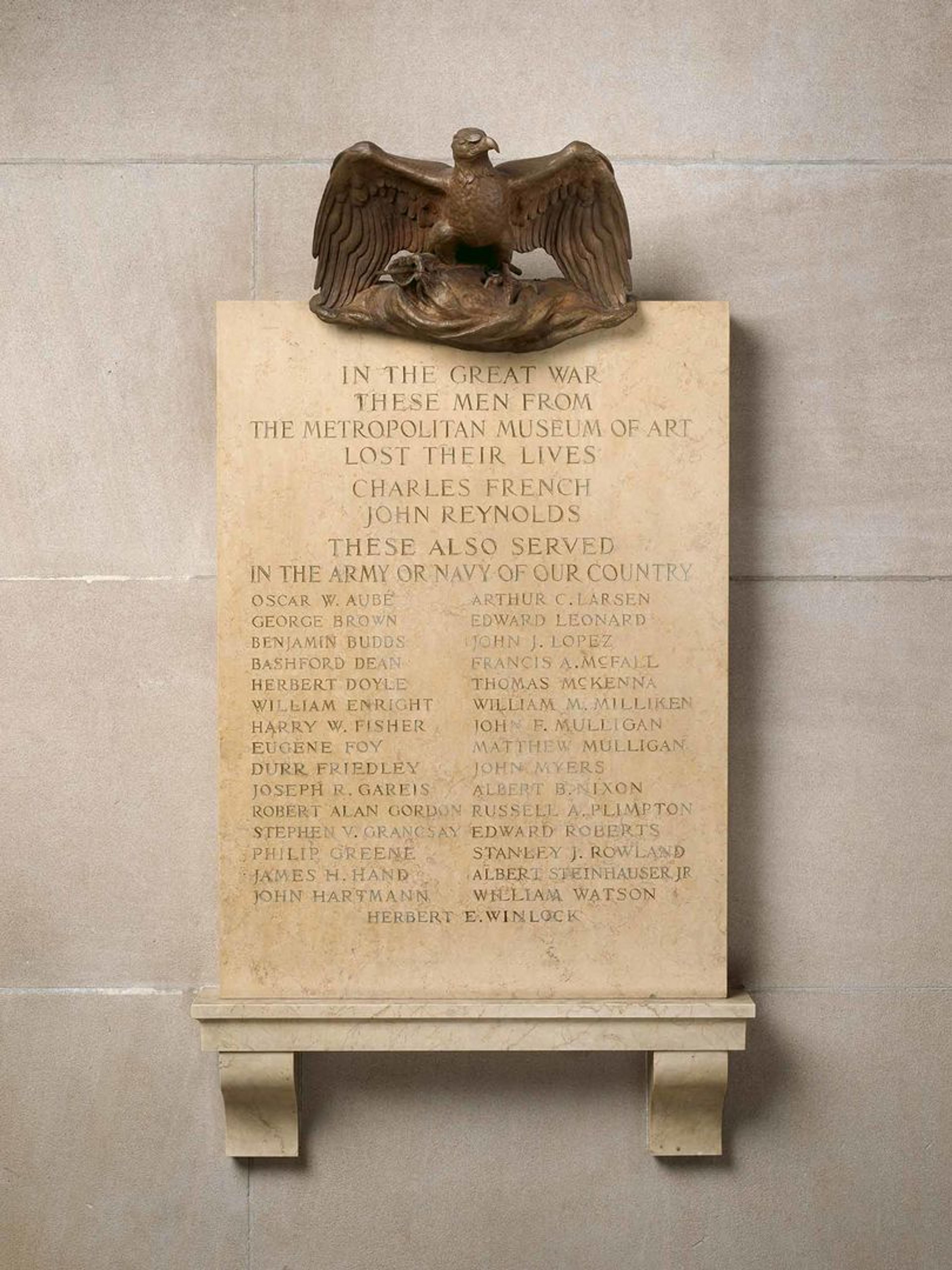

Two Met employees, Charles French (1893–1917) and John Reynolds (1891–1918), were killed in action during the war. A memorial tablet honoring the employees who served in World War I was unveiled in the Museum’s Great Hall in 1919, where it remains visible to this day.

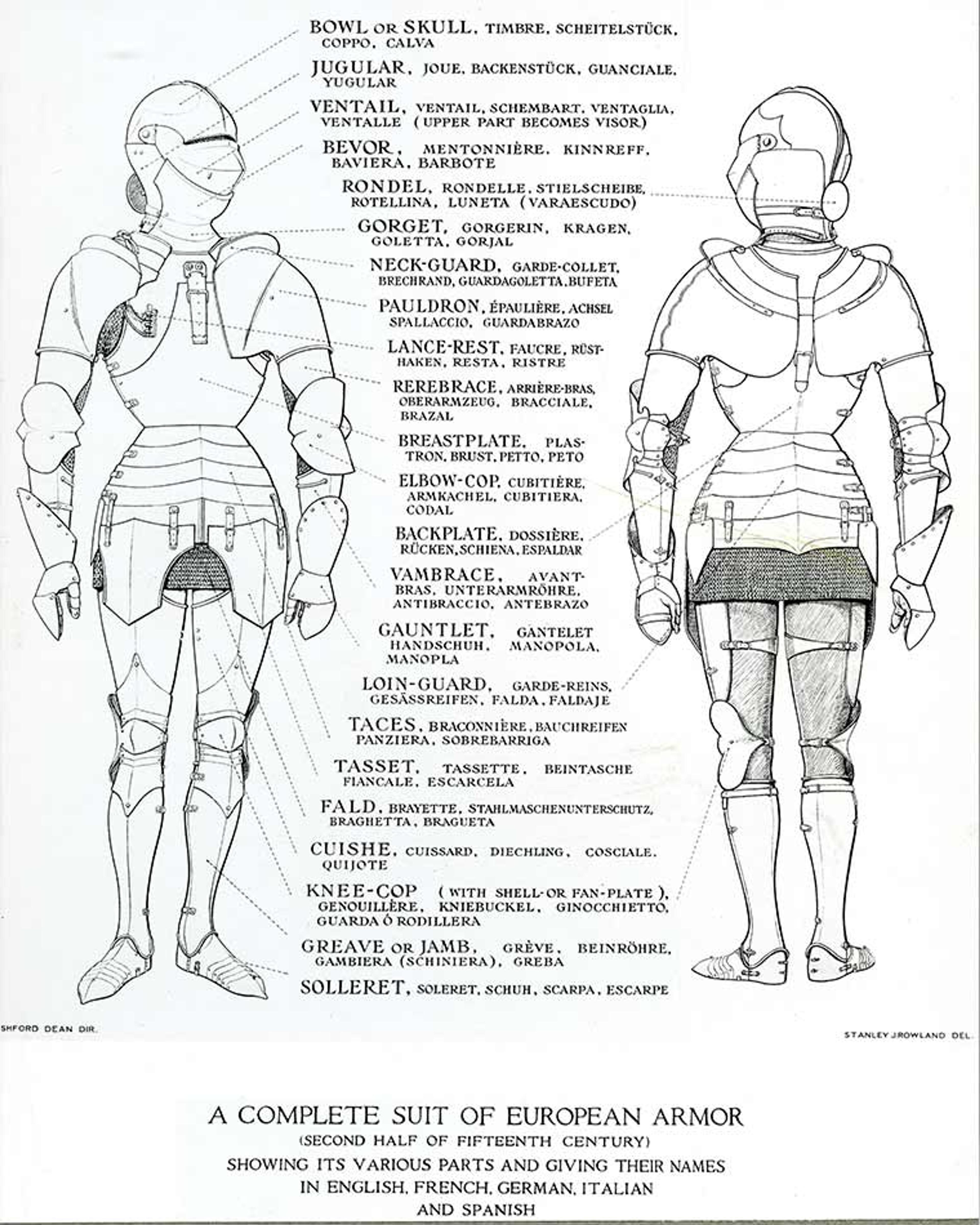

One such figure was Stanley J. Rowland (1891–1964), a promising young artist who had joined the Department of Arms and Armor in 1914. Employed to make technical drawings in pen and ink of works from the collection, he also conserved painted shields and etched the ornament on restored armor parts. As a draughtsman, Rowland worked closely with Dr. Bashford Dean (1867–1928), the department’s founding curator, to create much of the original artwork for an influential series of development charts designed to illustrate the history and typology of various types of armor and weapons. Their correspondence, preserved in the departmental archives, spans the period from 1917 to 1926. Their letters and postcards comprise one of the largest surviving personal exchanges between two Met employees during World War I.

Right: One of a series of development charts designed by Bashford Dean and drawn by Stanley J. Rowland. Dean gave Rowland a set to take with him when he went overseas on the chance he might be able to present them to any museum officials.

Like many Americans, Rowland volunteered for the military soon after the U.S. joined the war. He trained as a medical orderly at Roosevelt Hospital before sailing to England in June as a member of U.S. Base Hospital Unit No. 15. In his letters to Dean he describes the voyage as “a great pleasure trip” and “a delightful and really luxurious ten days at sea.” Upon arriving at the unit’s facilities in France in August, he praises the virtues of the base—“the air is pure and the water the best”—as well as its “excellent modern accommodations in one of the great buildings once gay with the activities of some of the most fashionable people in the country.”

Left: Ford Motor Company (American, founded 1903). American Helmet Model No. 8, 1918. Steel, leather, felt, canvas, bronze, pigment, sawdust. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund by exchange, 2012 (2012.473)

Dean himself quickly grew involved in the war effort, utilizing his vast knowledge of historical armor as head of a specially created unit tasked with the rapid development of helmets and body armor for U.S. troops. Within a few months he was commissioned as a major in the army and assigned to the Ordnance Department to carry out his work more effectively, shuttling frequently between New York and Washington, with visits to military posts in England and France. Dean worked closely with Met armorer Daniel Tachaux (1857–1928), who forged several non-ballistic prototypes of Dean’s designs, to produce approximately fifteen experimental helmet models in addition to armor for the torso, arms, and legs. Selected models were manufactured in numbers from a few hundred to a few thousand and sent to the front for field testing. Although none was adopted for use by the war’s end, Dean’s groundbreaking designs paved the way for the reintroduction of modern body armor as we know it today.

Rowland and Dean’s wartime correspondence is cordial and warm. Dean is pleased to receive Rowland’s vivid accounts, but also keen to impart a deeper understanding of the realities of war to his younger colleague. In response to one particularly enthusiastic letter about Rowland’s first impressions of France and its “good people,” Dean writes, “You have our congratulations and sympathy at the same time, for I know you will see a vast amount of suffering in the next weeks, but, of course, I suppose that is what we must all have to make our minds up to.”

Dean’s prediction proved accurate. By October, Rowland’s letters had grown sober. In one, he describes how the base received one hundred patients from Verdun: “Nearly all of them were burned by gas or crippled by having ‘trench feet.’ They were in water and mud—up to their knees some of the time—for three days.” By April 1918, Rowland was attempting, without success, to transfer from the Medical Corps to the Ordnance Department so that he could join Dean on the helmets and body armor project. Although it became clear that no transfers out of his unit’s Medical Corp would be allowed, he continued to try.

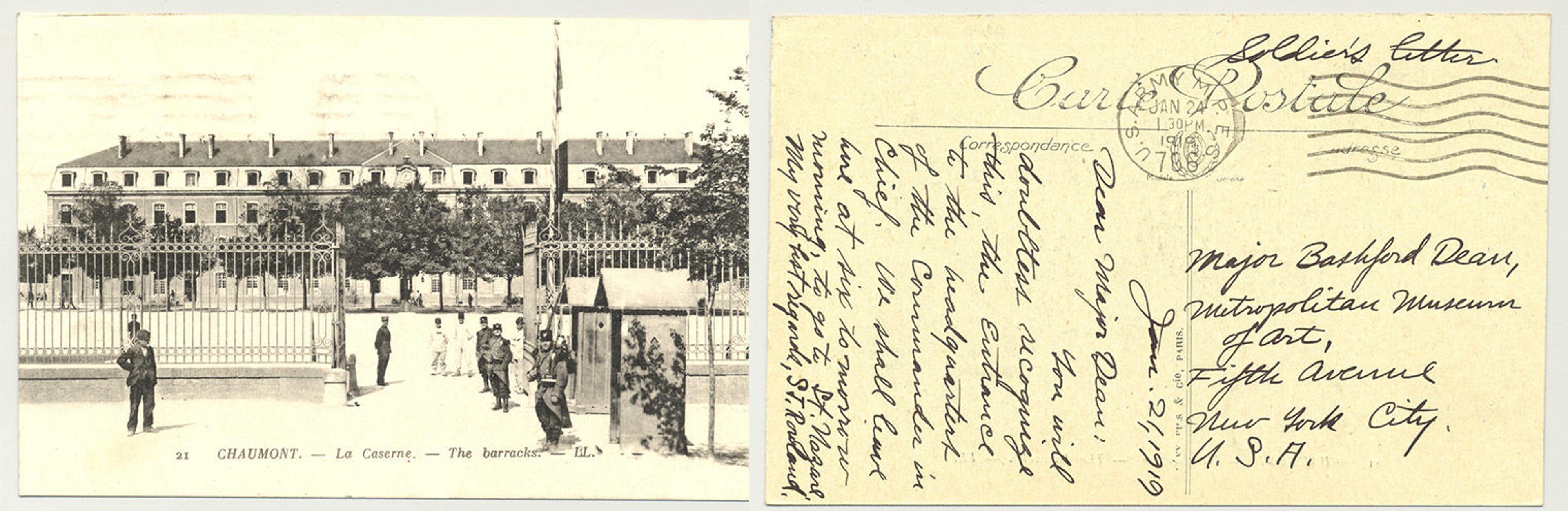

Postcard from Rowland to Dean, dated January 21, 1919, showing the barracks at Chaumont, France, of which Rowland writes “You will doubtless recognize this…the headquarters of the Commander in Chief.”

“Fifteen months of hospital work has been enough for me,” Rowland wrote to Dean in October 1918, “though the work if properly done is worthy of the very best there is in a man.” He continued to say that he hoped to go the front, where he might get shot and possibly sent home. Still, he maintained that he had “never grown really tired of the life here as many of the fellows have.” The following month, on November 12, one day after the Armistice was signed that brought an end to the war, Dean replied that he was pleased to “learn that you have been sticking to your difficult and philanthropic work with such marked success… had I been in your position I should have had no nerves left at all.”

Their final wartime exchange is a postcard dated January 21, 1919, written the day before Rowland began his return journey to the United States. Upon returning to The Met, Rowland stayed on as a trusted and productive member of the department for several more years. His most notable and challenging work for the Museum was probably the conservation in 1924 of an extremely rare and important group of fifteenth-century German painted shields. In the late 1920s, Rowland left the Museum to pursue a long and successful career as a painter.

Staff of the Department of Arms and Armor, photograph taken in fall or winter of 1919. Of the six men pictured, four (Stanley J. Rowland, Stephen V. Granscay, Raymond Bartel, and Bashford Dean) served in uniform during in the war some capacity.

Read more about World War I and the Visual Arts in the Bulletin and on the website for the 2017–18 exhibition, organized by Jennifer Farrell, Associate Curator in the Department of Drawings and Prints. For art and the 1918 flu pandemic, see this Time Magazine article from May 2020, with contributions from Jeff Rosenheim, Curator in Charge of the Department of Photographs.

[1] “Report of the Trustees for the Year MCMXVIII,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 14, no. 3 (March 1919), p. 48.

[2] “Art Museum has $244,499 Deficit,” New York Times (January 21, 1919), p. 9.

[3] Claude Monet to Gustave Geffroy, December 1, 1914 (WL 2135), in Claude Monet: Biographie et catalogue raisonné, ed. Daniel Wildenstein, vol. 4 (Paris: La Bibliothèque des Arts, 1985), 391.