When they say that books tell you a story, they don’t usually mean it literally. But during my time as the 2024 Adrienne Arsht MuSe Intern in Watson Library’s Book Conservation Department, I encountered a group of books with actual voices—or at least, books that produce audible sounds. My investigation into books with audio elements began because of my dual interests in both book conservation and time-based media conservation, which addresses artworks that incorporate a time-based element, often video, audio, or digital.

The integration of audio elements in books creates a unique sensory experience that blurs the lines between the visual and auditory arts. This article explores three works that incorporate sound in innovative ways: Pilina Everlasting by Allison Leialoha Milham from Watson’s collection, and two publications by Visionaire, Spirit and Sound from the Costume Institute library. Each of these works offers a distinct approach to combining traditional book formats with audio, resulting in a multisensory experience that enhances the narrative and emotional impact. This dispatch from Watson will delve into the artistic intentions, preservation challenges, and unique auditory experiences provided by these objects in The Met collection.

Cover of Allison Leialoha Milham's Pilina Everlasting (San Luis Obispo, California: Allison Leialoha Milham, 2022)

“Drawing on Indigenous ways of knowing and the ever-shifting volcanic landscapes of Hawaiʻi Island, ‘Pilina Everlasting’ is a meditation on loss and love that honors my experience of grief and the ways I've found healing through forging new intimacies with ʹāina (the land) and nā kūpuna (my ancestors). The sounds and sequences of text & image offer moments of connection and belonging within an ever-changing environment, cycling through life and death. Themes of pilina (connection, relationship), loss and transformation are explored through music and print.”

—Allison Leialoha Milham

Pilina Everlasting is an artist’s book designed and hand-bound by Allison Leialoha Milham. An artist’s book in its simplest definition is an artwork in the form of a book. Unlike commercial publications, artists’ books are often designed, printed, and bound entirely by one person and are either one-of-a-kind or extremely limited edition. In this case, all elements were designed and assembled by Milham herself, and she released an edition of only eight copies. From this, we can infer that each choice Milham made when creating this artist’s book was fully intentional.

Milham began work on Pilina Everlasting in 2018 during a month-long residency at Hawai'i Volcanoes National Park, following the loss of her mother to pancreatic cancer. The piece is presented as a portfolio-style cloth box containing a tray with two small books, an artist’s statement, and a 7-inch lathe-cut record. When opened, the box plays an approximately 120-second sample of the record. The audio for this book operates much in the same way that a musical greeting card does, with a circuit interrupted by a thick strip of acrylic plastic that pulls away when the box is fully opened, thus finishing the circuit and causing the music to play. The music is played by a piezoelectric speaker powered by an alkaline button cell battery. Piezo speakers have unique auditory characteristics, including the fact that they are limited in reproducing low-frequency sounds due to their low displacement capability. They also have a narrow dispersion pattern compared to other speakers, meaning that they project noise in one focused direction rather than a broader cone pattern. This causes the sound to feel shockingly intimate, almost as if someone is talking directly to the listener from close proximity.

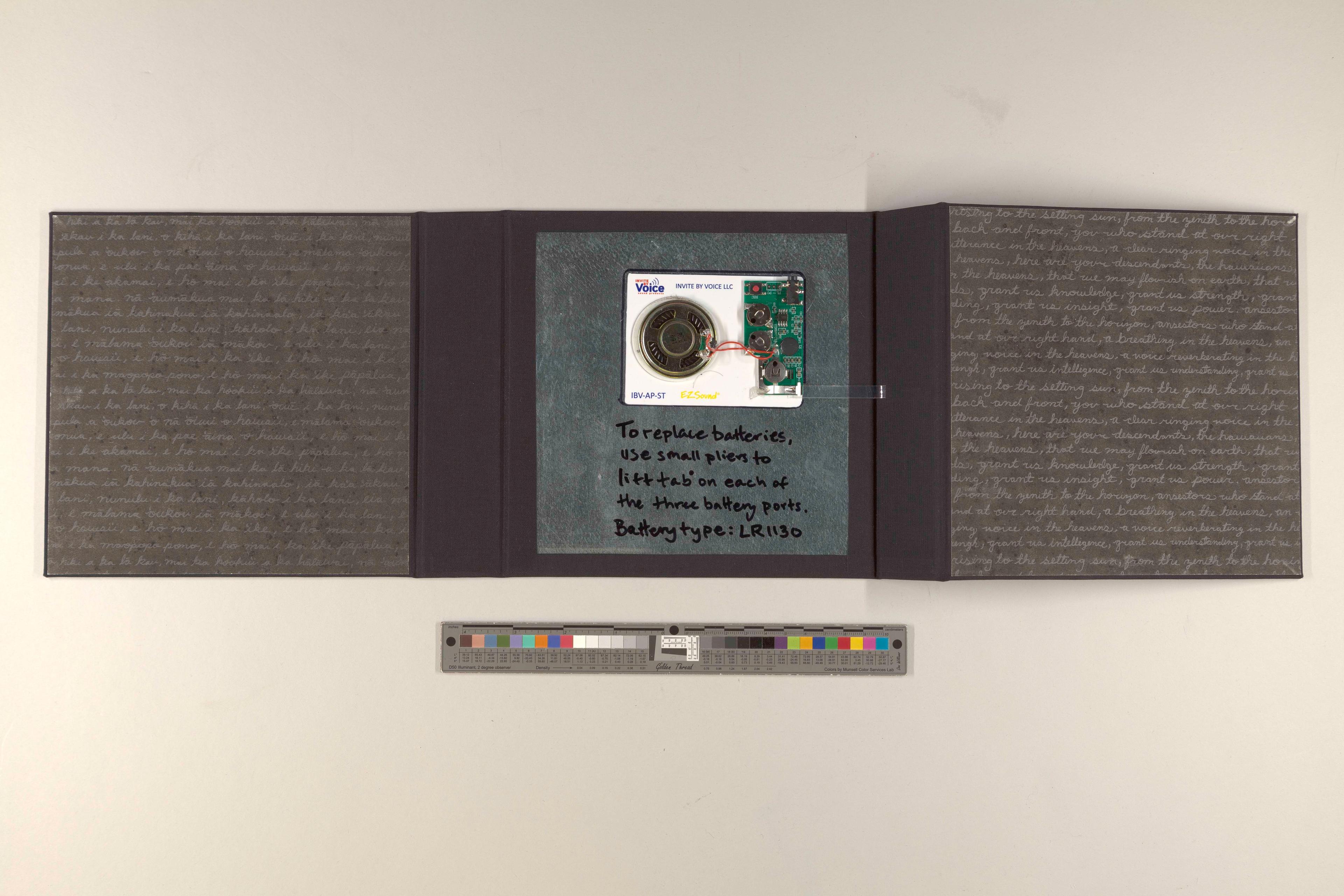

Interior of Allison Leialoha Milham's Pilina Everlasting (San Luis Obispo, California: Allison Leialoha Milham, 2022)

The characteristics of the piezo speaker significantly influence the experience of interacting with Pilina Everlasting. Though the artist’s book includes three formats of Milham’s recorded song (the digital file, the vinyl record, and the piezo speaker in the box), each one carries a unique holistic sensorial experience. Because the piezo speaker plays each time the box is opened, it is at risk of deterioration, likely through battery failure. Luckily, Milham has made maintenance of this recording more accessible, as the tray on top of the mechanism is magnetic and therefore completely removable in the event that the batteries need to be changed. Milham’s forward-thinking design indicates that the audio-component generated by the piezo speaker is essential to her intent, which informs preservation decisions.

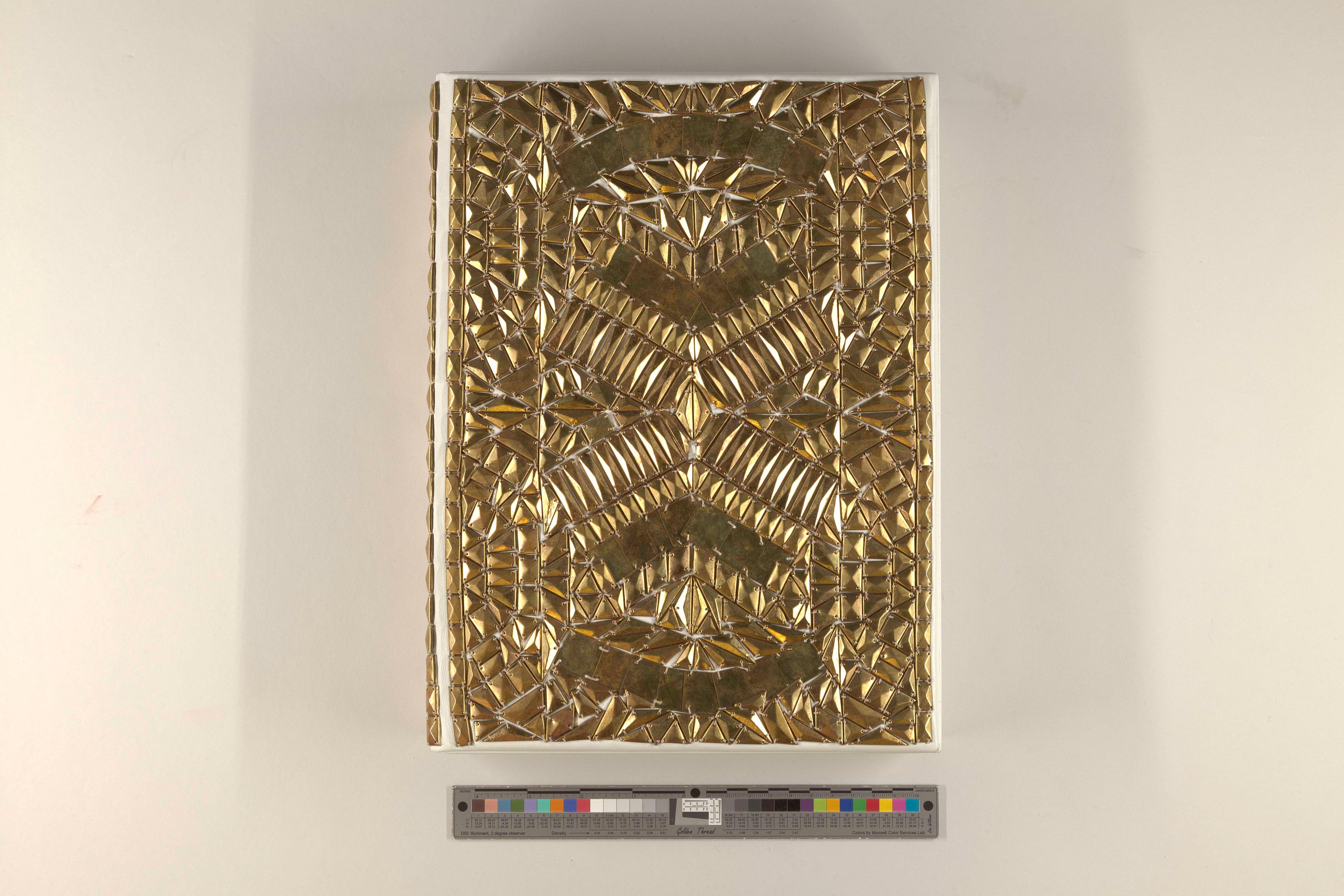

Cover of Visionaire 58: Spirit: A Tribute to Alexander McQueen (New York City, NY: Visionaire Publishing, 2010)

Like Milham’s artist’s book, Spirit: A Tribute to Alexander McQueen, a 2010 publication by Visionaire, includes an audio component. Visionaire is a New York-based company that produces art publications which they call multi-format albums of art and fashion. Artists they work with are given “unparalleled freedom to push Visionaire’s original formats.” Spirit includes a series of plates within a leather clamshell box that, when opened, play a Lady Gaga song. However, the copy held in the Costume Institute Library at The Met does not currently play music. Its speaker is probably powered by a lithium coin cell battery, which has a shelf life of about 10 years; it’s likely that the battery life has run its course since Spirit’s 2010 publication.

While restoring the audio function by replacing the battery might seem to be a straightforward choice, there are many factors that a conservator weighs when deciding if an object should be ‘fixed.’ In contrast to Milham’s work, where the artist ensured easy access to the batteries, the electric speaker for Spirit is embedded in the leather box. Changing the battery would require a more invasive approach, requiring the conservator to lift the leather covering the box, which could compromise both its visual and structural integrity; treatment would need to be repeated or modified if the battery needed to be changed again down the road. To justify that level of treatment, the volume’s use and the artistic intent would need to be taken into consideration.

But Spirit contains other materials that might inform the conservator’s decision-making; this edition of Visionaire is a tribute to Alexander McQueen, created shortly after his death. It is a collection of images inspired by McQueen that were printed on paper embedded with seeds. When planted, the paper would bloom into wildflowers. The wildflowers would of course then also naturally run the course of their life and die, reflecting “a statement about the transience of life and fashion that honored [McQueen’s] vision.” So, perhaps like wildflowers and fashion movements themselves, the battery has also naturally run the course of its life.

Visionaire 53: Sound (New York City, NY: Visionaire Publishing, 2008)

The last work is Visionaire’s fifty-third publication Sound, presented in a black domed acrylic box containing five 12-inch vinyls each with an A and B side, two CDs with the complete track list, and a battery operated MINI clubman car that serves as a record player and is designed to ‘drive’ around the vinyl as it plays. Of the three publications discussed here, it is the furthest from what is traditionally considered a book, with the only real textual element being the small handbook that includes the track list and instructions for use. But it does present its vinyls in an unorthodox, arguably book-like manner. The stack of two-sided records resembles a textblock that can be ‘read’ front to back, with each of the vinyl records like a page.

Visionaire 53: Sound (New York City, NY: Visionaire Publishing, 2008)

The records present an interesting paradox from a preservation standpoint. The inclusion of a bespoke portable record player adds an element of play on top of the utility that seems to highly encourage the use of the vinyls. But use of the records, even with the utmost care, would cause degradation. Oils from one’s finger, microscopic dust and debris in the air, and mechanical abrasions from regular use of the portable player can all cause damage leading to loss of audio quality. Not to mention, the MINI clubman player is also referred to as a “vinyl killer” due to its tendency to damage the vinyl more quickly than a standard player. Since the image on each vinyl record is a work of art in its own right, each play of the record would progressively destroy the visual image.

Visionaire 53: Sound (New York City, NY: Visionaire Publishing, 2008)

Unlike the previous two works, where the audio and visual components work in tandem, Sound is an exercise in choice between one or the other. However, not playing the vinyls might have consequences as well. The records contain unreleased audio experiments, samples, spoken word pieces, and songs, some of which are not accessible anywhere else. If library patrons were frequently requesting to listen to the audio available only on the vinyl records, there might be a strong argument for creating a digital preservation copy. However, this raises questions about whether a digital surrogate could replicate the experience of interacting with the actual object. Record enthusiasts often claim that vinyl produces a superior, warmer sound. From a technological standpoint this is untrue—digital files are theoretically capable of replacing any tonality—which was proven in a double-blind MUSHRA (Multiple Stimuli Hidden Reference and Anchor) test.

It must be recognized, however, that presentation affects perception. In addition to the analog format of the records, the bespoke portable player adds an element of play to the listening experience. Digitization would lead to the loss of the holistic experience: the Visionaire publications are very deliberately ostentatious, and the performance element of it cannot be captured with a digital surrogate. Of course, being part of the collection of a research library, there is no feasible way that one could justify letting people regularly use the vinyl killer, nor am I suggesting that. How to inform researchers who are using this publication of the full complexity of the piece, even if they cannot use it in that way, is an important curatorial consideration.

Visionaire 53: Sound (New York City, NY: Visionaire Publishing, 2008)

Because the materials that books are made of have remained largely unchanged for centuries, these volumes challenge us both conceptually and practically. They ask the reader to reconsider how books are used and present unique dilemmas for storage and preservation. Pilina Everlasting, Spirit, and Sound illustrate the complexities of maintaining original auditory features, as each requires careful consideration of the artist’s or publisher’s intent, and the materials used. From the easy battery replacement in Pilina Everlasting to the more invasive procedures needed for Spirit, the preservation efforts must balance maintaining the integrity of the work with practical accessibility.

Working with volumes like these requires book conservators to learn about new materials and technologies and consult or collaborate with experts in other conservation specializations. Moreover, the debate over using vinyl records in Sound underscores the tension between usage and degradation. As artists and publishers continue to experiment with audio elements, the potential for creating immersive, interactive experiences that resonate on multiple levels will undoubtedly expand, inviting us to explore the intersection of sound and sight in ever more creative ways. And with it, addressing preservation challenges will be essential to ensure that these multisensory experiences remain intact for future audiences.