In 1906, an assistant curator of paintings at The Metropolitan Museum of Art began collecting current newspaper obituaries of recently deceased artists. Arthur D’Hervilly, who started his Met career as a guard in 1894 and worked his way up through the ranks, was preparing a checklist of American paintings and helping senior curators to revise a catalogue of the entire Met picture collection. D’Hervilly likely began to gather artist obituaries because they included basic biographical information about contemporary artists represented in The Met catalogs.

Artist Obituary Scrapbook, Volume 2 (1915–1929), pages 54–55

His main source for obituaries was the National Press Intelligence Co., a news clippings bureau. Their staff read hundreds of daily papers each day, searching for personal names, terms, and concepts requested by customers. Articles containing target phrases were clipped and delivered to subscribers who had requested specific searches.

The Met had for many years received from National Press Intelligence batches of clippings related to the Museum itself—articles about its exhibitions and programs, milestone art acquisitions, gallery expansions, and activities of its trustees, benefactors, and staff. For more than a century, these stories were gathered and pasted chronologically into dozens of large scrapbook volumes that now comprise a vast repository of information about the Museum’s past.

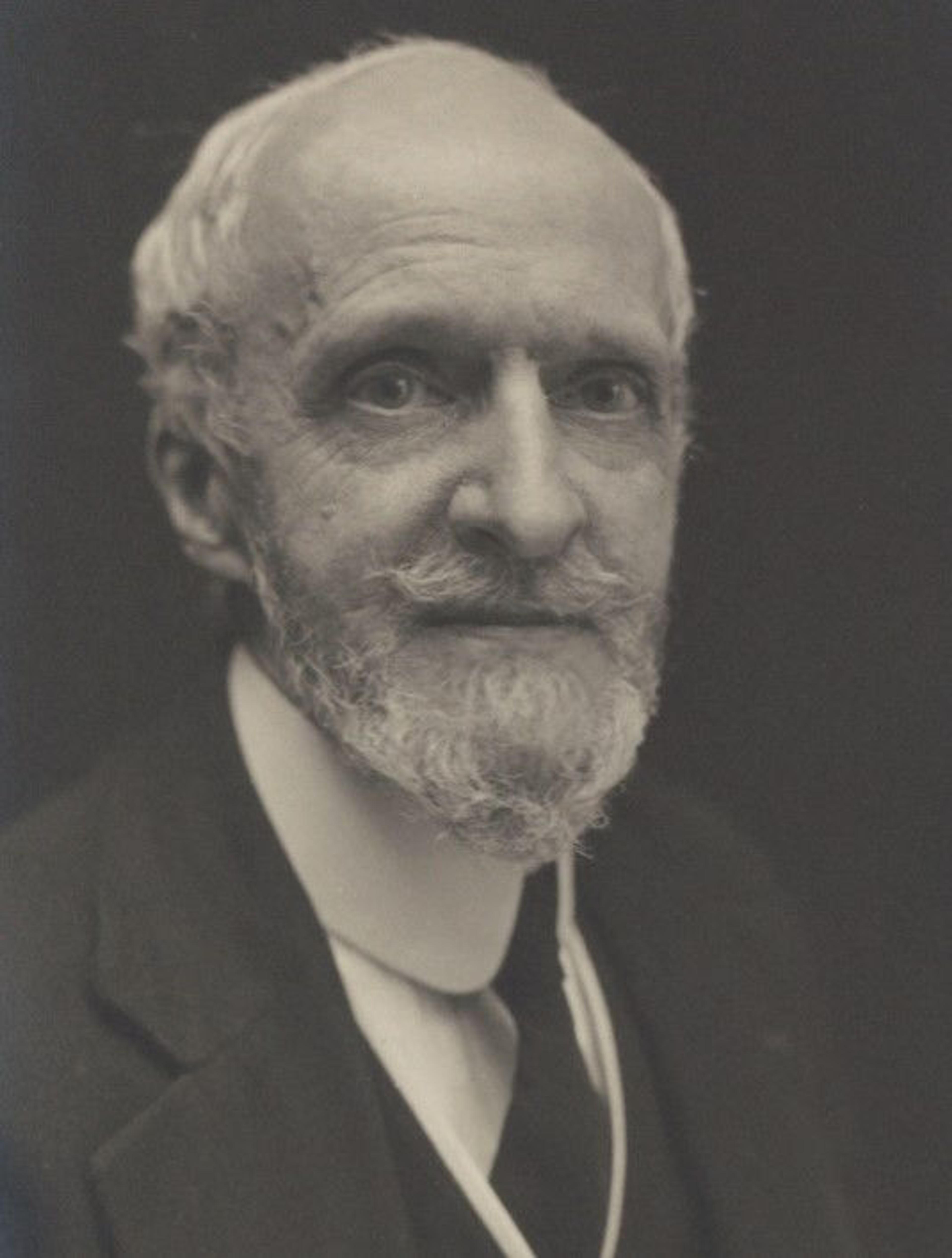

R. Liebig, Arthur D’Hervilly, ca. 1915, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives

During my tenure as Managing Archivist of the Museum, from 2008–2023, I often dipped into this journalistic treasure trove of reporting on high points in Met history. But for years I overlooked the unique, outlier series focused on artist deaths that was initiated by Arthur D’Hervilly, only stumbling upon it while trolling through the stacks for material to include in the sesquicentennial exhibition and catalog Making the Met, 1870–2020.

Delving deeper into D’Hervilly’s long career at the Museum, I found that he methodically acquired obituaries until his own death in 1919. Other Museum staff followed his lead for another decade, amassing hundreds more artist death clippings. All were pasted into two large scrapbook volumes that grew to contain over three hundred densely packed pages. The first volume spans 1906–1915, while the second covers the years 1915–1929. The scrapbooks were for many years shelved in the stacks of the Thomas J. Watson Library, and were transferred to the Met Archives around 2010 on my watch.

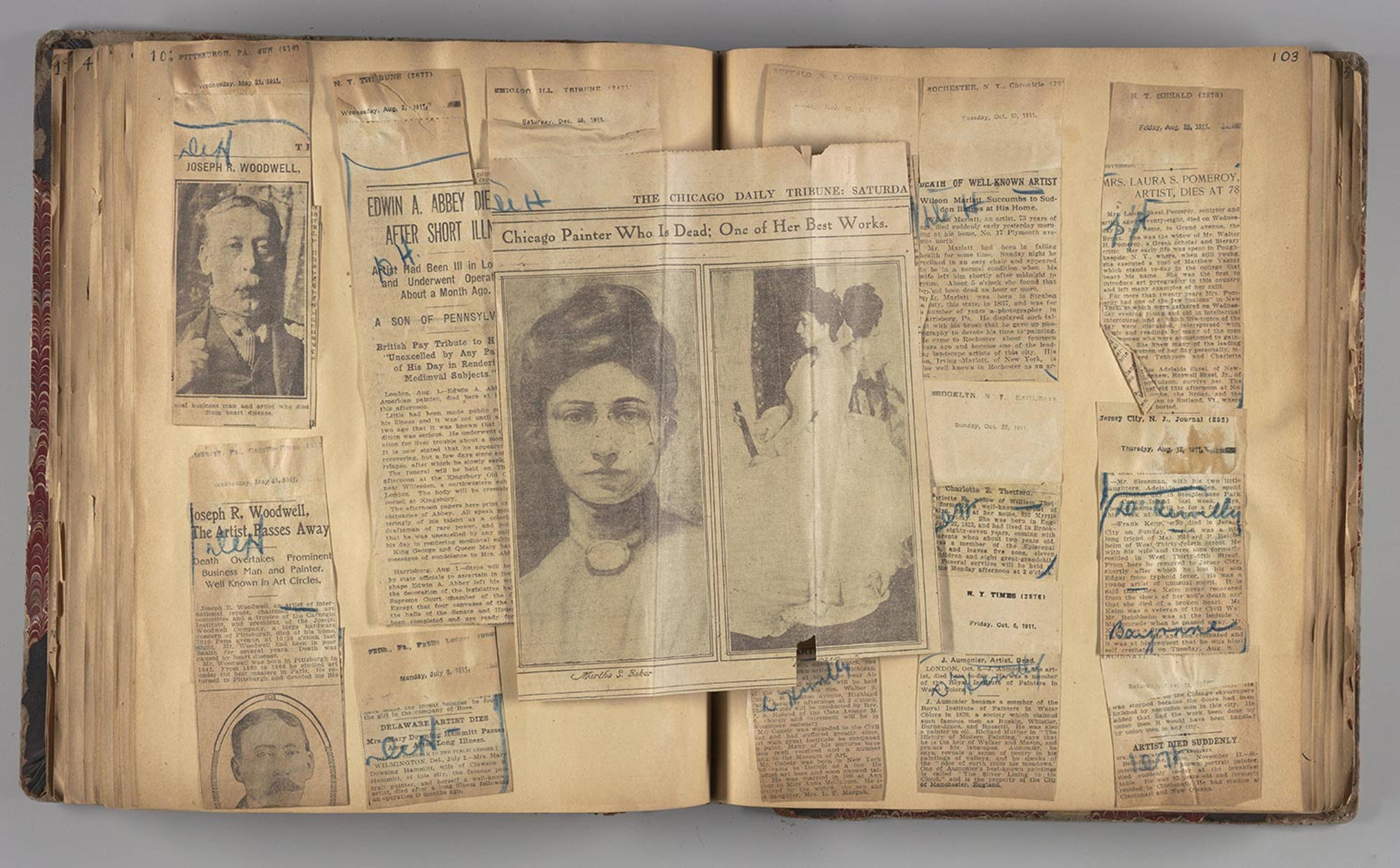

Artist Obituary Scrapbook, Volume 1 (1906–1915), pages 102–103

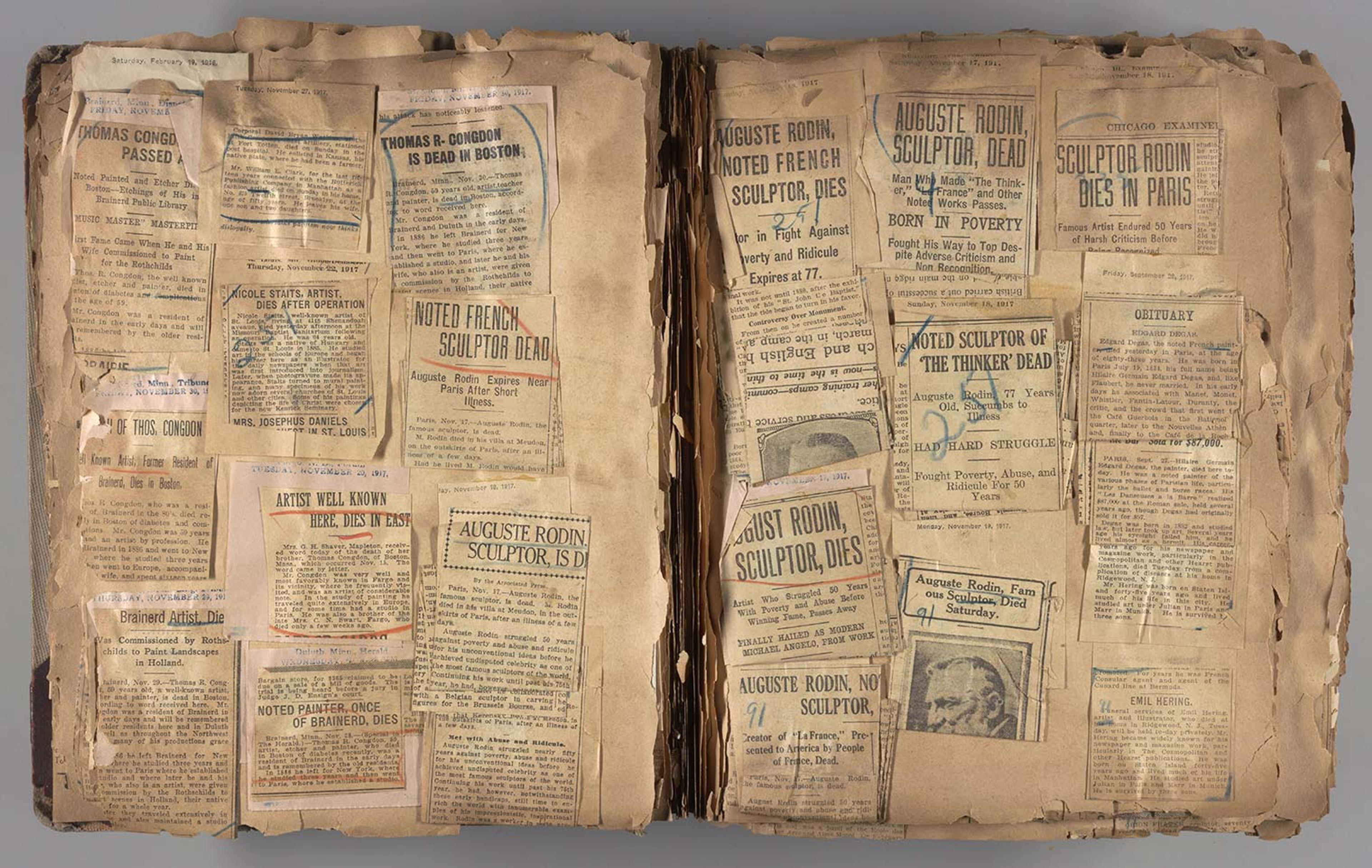

Artists memorialized on their pages include painters, sculptors, commercial illustrators, and photographers. Some were world famous, like Auguste Rodin and Winslow Homer, but most were little-known at the time and are forgotten today. Moreover, tabloid reporting from the heyday of yellow journalism sensationalized those who died by violence, bizarre accidents, poverty, or suicide, adding a macabre dimension to the collection. Intrigued by these morbid relics of art history, I spent several years researching the backstory of their creation. My book, Deaths of Artists (Blast Books, 2024), intertwines the peculiar biography of Arthur D’Hervilly—an ex-convict and frustrated painter—with heart-wrenching, bizarre, and darkly comic stories of artist deaths preserved in the scrapbooks.

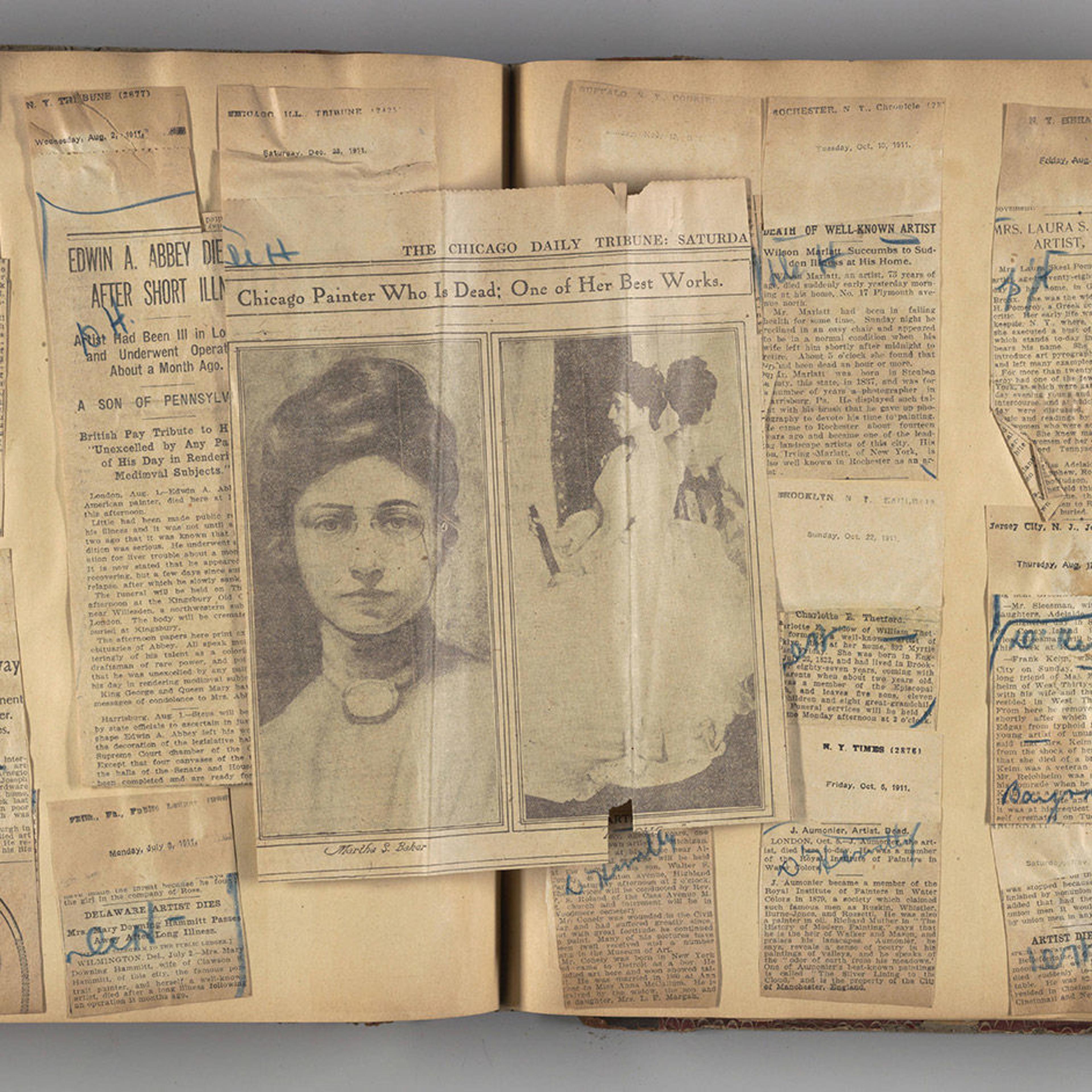

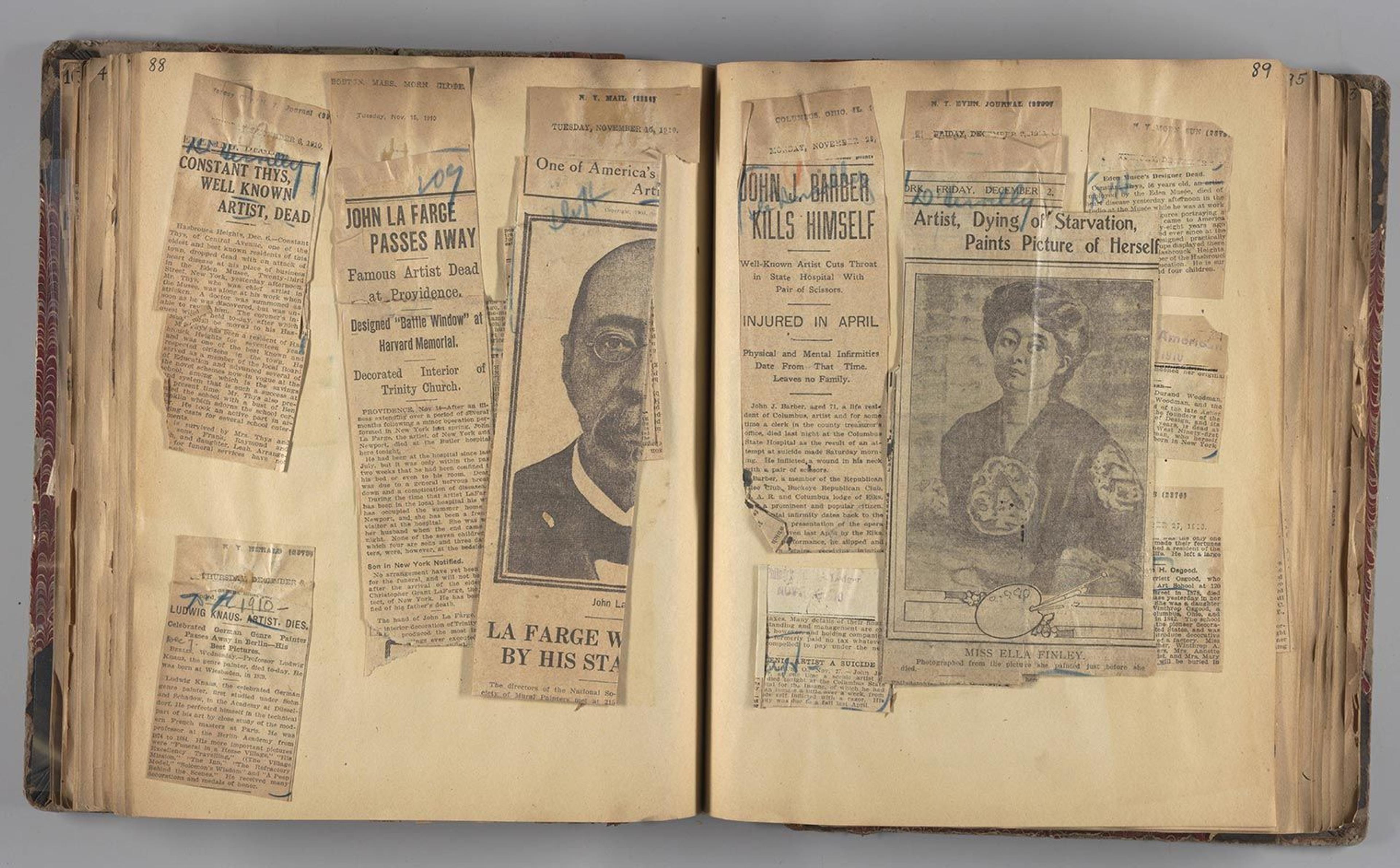

Artist Obituary Scrapbook, Volume 1 (1906–1915), pages 88–89

They include Ella Finley, an obscure painter and sculptor who starved in her Philadelphia studio while daubing at a tender self-portrait; Frank Millet, a renowned genre and historical painter—and Trustee of the Metropolitan Museum—lost aboard the Titanic; and August Obermuller, an elderly photographer of circus and sideshow performers, who drowned in a vat of photo chemicals.

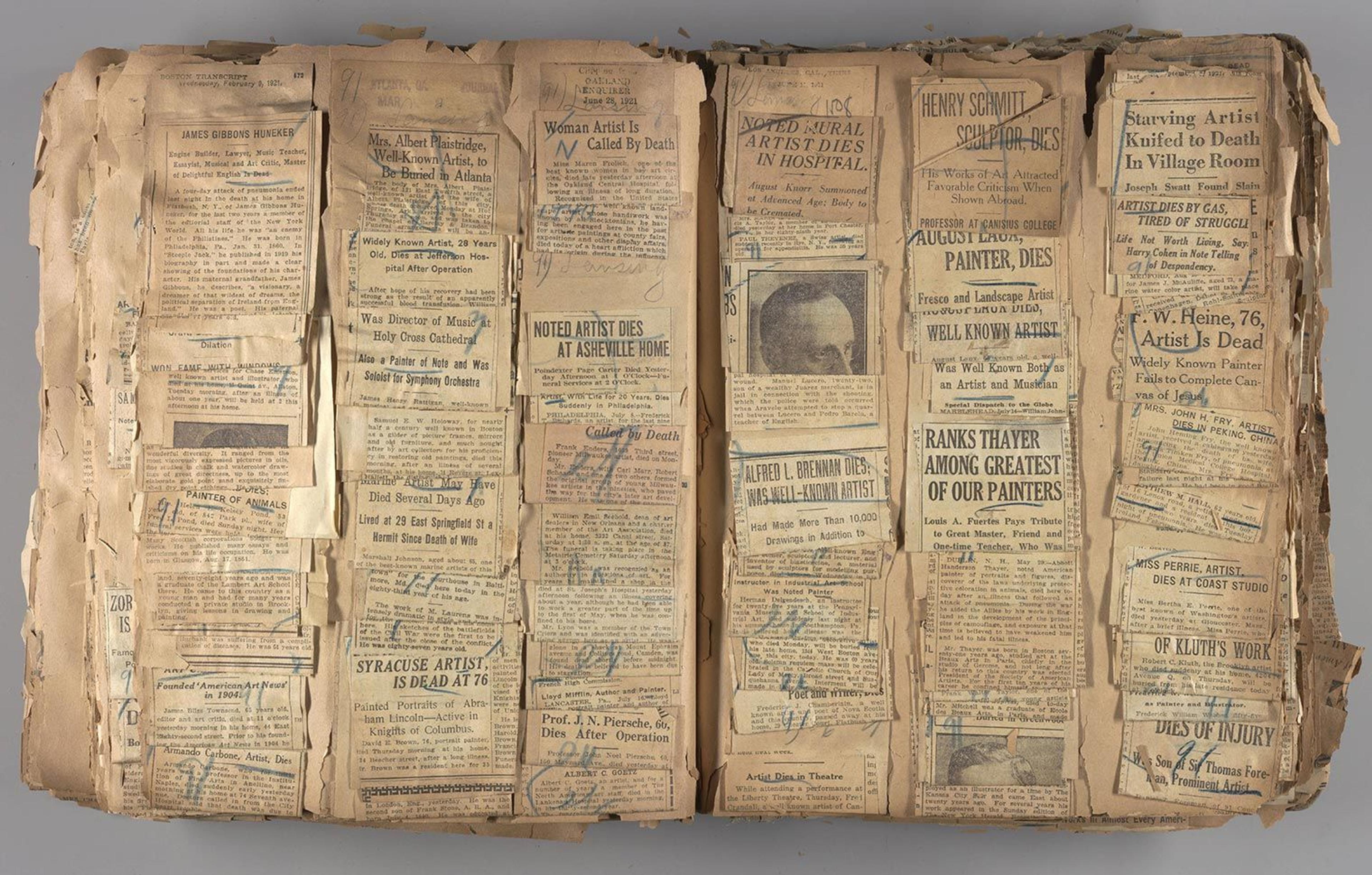

While researching the book, I found that hundreds of the obituaries collected by D’Hervilly and later Met staff were folded before they were glued to the pages, and many others were pasted right on top of one another. Moreover, newspapers of the time were printed on cheap wood-pulp paper, so most clippings have deteriorated since the scrapbooks were compiled. Sadly, it was impossible to unfold and read many of the obituaries without causing them irreparable damage, so I was often stymied in my efforts to glean detailed information about particular artists represented in the collection. Fortunately, by searching headline phrases and personal names still visible in news ledes affixed to the surface layer of scrapbook pages, I was able to locate and read the full text of many stories in the Library of Congress Chronicling America collection, an online database of hundreds of American newspapers published from 1756 to 1963.

Artist Obituary Scrapbook, Volume 2 (1915–1929), pages 96–97

At the same time, I recognized that the fragility of the scrapbooks would make it difficult for archivists to share this compelling material with future researchers—overhandling of the analog originals would cause them to decompose entirely within a relatively brief time. I brainstormed with Met librarians, conservators, and photographers about techniques to provide some level of access to this remarkable, but vulnerable, collection. All agreed the artist obituary scrapbooks should be systematically photographed at high resolution to establish a complete visual record of their current state, and that the resulting images should be made freely accessible for public viewing. Thomas J. Watson Library Digital Collections, which provides online access to digitized versions of rare and unique materials housed in Met libraries, archives, and study centers, provided the perfect venue for open access.

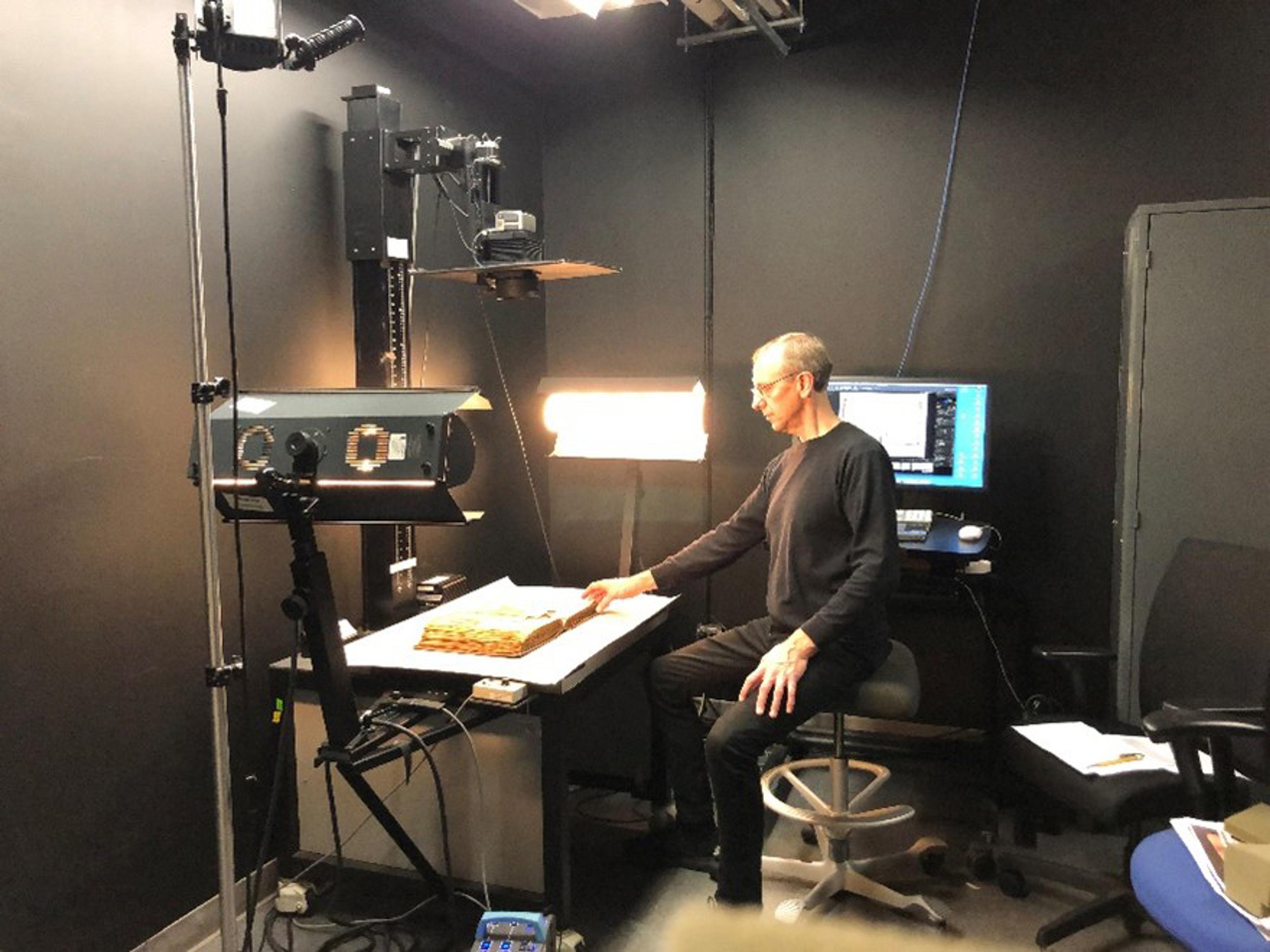

Jim Moske, Self-portrait with obituary scrapbooks in the Met Imaging studio, 2023

During spring and summer 2023, Museum Archives intern Maggie Nevison and I photographed every page of the two volumes in the Met Imaging studio, using a Hassleblad camera positioned on a copy-stand usually devoted to documenting Met artworks on paper. We were grateful for training and technical support provided by the Imaging team, especially Scott Geffert, Teri Aderman, and Chris Heins. In April 2024, Met librarians Robyn Fleming and Daisy Paul organized the resulting 161 images of two-page scrapbook spreads, created metadata and catalogue records, and loaded everything to the Watson Digital Collections site (available here).

Today, this virtual presentation of the scrapbooks allows online readers to page through the entire collection, to read complete obituaries when they are visible (especially on the first pages of volume 1) and to glean an impression of the contents of the most densely packed and damaged pages (prevalent in volume 2). Unfortunately, the fragmentary condition of much of the original material hindered efforts to render the collection full-text searchable, though it is possible this feature may be added to the collection in the future. Nevertheless, viewers around the world can now browse, interpret, and respond to these grim fragments of the past that not only record the facts of artist’s deaths, but also stimulate ideas and questions about their lives. By presenting the artist obituary scrapbooks to the widest possible audience, we hope to inspire a sense of wonder at the unique challenges artists face, the exceptional risks they take, and the cruel turns of fate that often thwart their efforts.