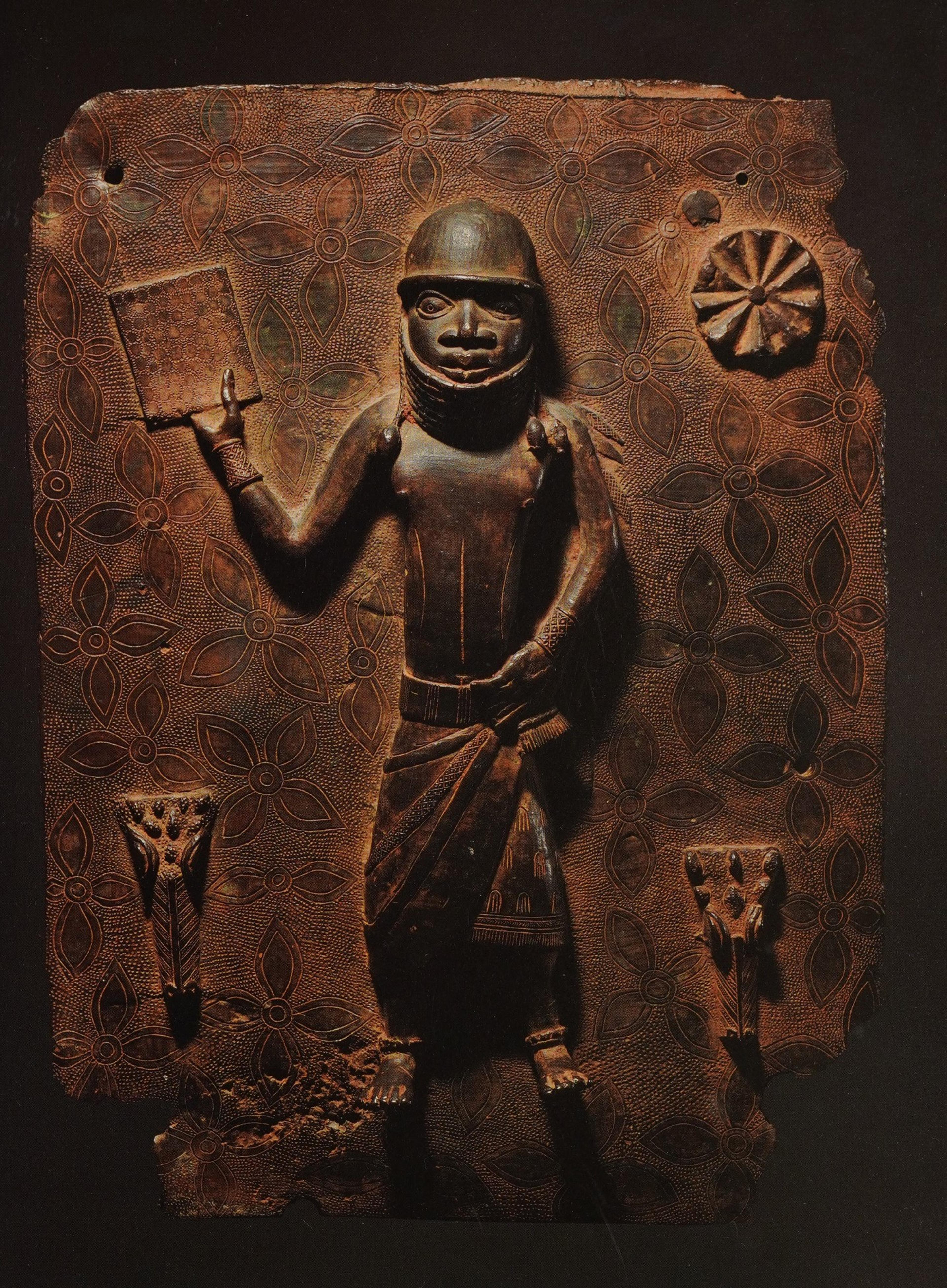

In February of 1897, Benin City, in what is now modern-day Edo State, Nigeria, was sacked and burned by an expedition of British forces. Often referred to as a punitive expedition, it was mounted after an unauthorized British delegation of roughly 250 men was ambushed and killed by Benin forces in January 1897. In the centuries prior to the sacking, Benin City was a place of immense wealth with a material culture to match. After the city was sacked, thousands of artworks and cultural artifacts, including the famous Benin Bronzes, were looted and transported out of the region. The treasures then hit the European art markets and were sold to collectors and museums all across Europe and North America.

In February of 2023, after noting that The Met’s Thomas J. Watson Library had contributed several auction catalogs featuring Benin art to the Internet Archive, staff from a project called Digital Benin reached out to inquire about whether we had any additional material that could be digitized and integrated into the platform. Digital Benin is an online platform that brings together a wide range of documentation to provide an overview of looted artworks and cultural artifacts from the historic Kingdom of Benin. The project focuses on the artistic, historical, and cultural importance of these artifacts. Institutions from all over the world have contributed to the platform, with over 5,000 objects, 136 institutions, and 20 countries represented.

Sotheby’s. Collections Charles Hug, Andrea Portago, Roger Vanthournout, Helmut Zake et divers amateurs: art d'Afrique, d'Océanie et des Amériques: Auction in Paris, June 23, 2006. Lot 122 (Paris: Sotheby’s, 2006)

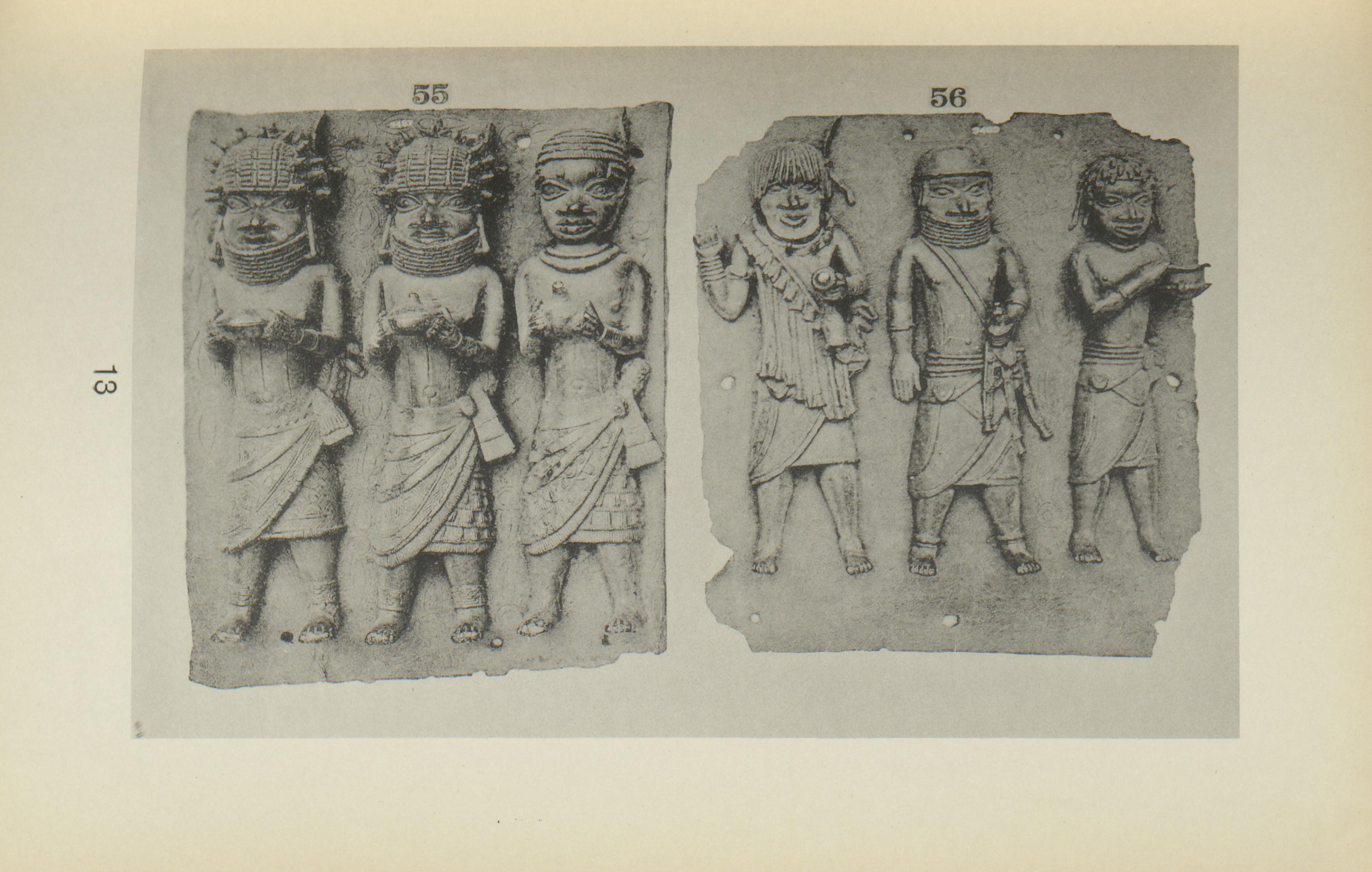

Digital Benin brings together many types of resources, but the staff was interested in our auction catalogs to track the movements of artworks as they were sold and changed hands over the years. While many of the looted artworks are accounted for in various museum and private collections, there are still many more that are missing. Digital Benin was hopeful that The Met had more to contribute on this front, and this is where Watson Library joined the conversation.

In Watson, we have an extensive collection of nearly 145,000 art auction catalogs, dating back to the seventeenth century. Many of them, especially the older ones, are annotated by hand with valuable information like the sales price or the purchaser. These factors make our copies highly valuable to provenance researchers, and as such, are some of our most circulated material.

While it is wonderful that our catalogs see so much use, it does present us with some issues. Many of the catalogs are old and brittle. Even careful handling isn’t enough to prevent damage to the most fragile catalogs in the collection. At some point, we realized that if we want people to be able to use the catalogs well into the future, we needed to take steps to preserve them. Our solution was to have the catalogs digitized and moved into storage so that the physical copies are subjected to minimal handling without compromising our patrons’ access to the valuable marginalia within.

We do this through a partnership with the Internet Archive, who digitize thousands of auction catalogs for us every year. The scans produced are then freely available to anyone interested. To date, over 10,000 have been digitized. Not only does this partnership help us preserve the physical copies of the catalogs by limiting handling, it also expands access to these resources by making them available to anyone with internet access. This is how the researchers from Digital Benin found our catalogs and what led them to contact us.

Believing in the importance of Digital Benin’s project, we jumped at the opportunity to contribute. We decided to incorporate any catalogs for this project into the existing workflow for digitizing materials through the Internet Archive.

To identify catalogs that would fall under the purview of this project, I began in what is likely the most obvious place: a keyword search for “Benin” in our online catalog, Watsonline. This search returned around 40 results for auction catalogs with the word “Benin” in the title. This was a great place to start, but I felt like there was definitely more to be discovered. Many of the titles that appeared in that initial search had either already been digitized or ended up not containing relevant information. I needed to expand my search and get creative.

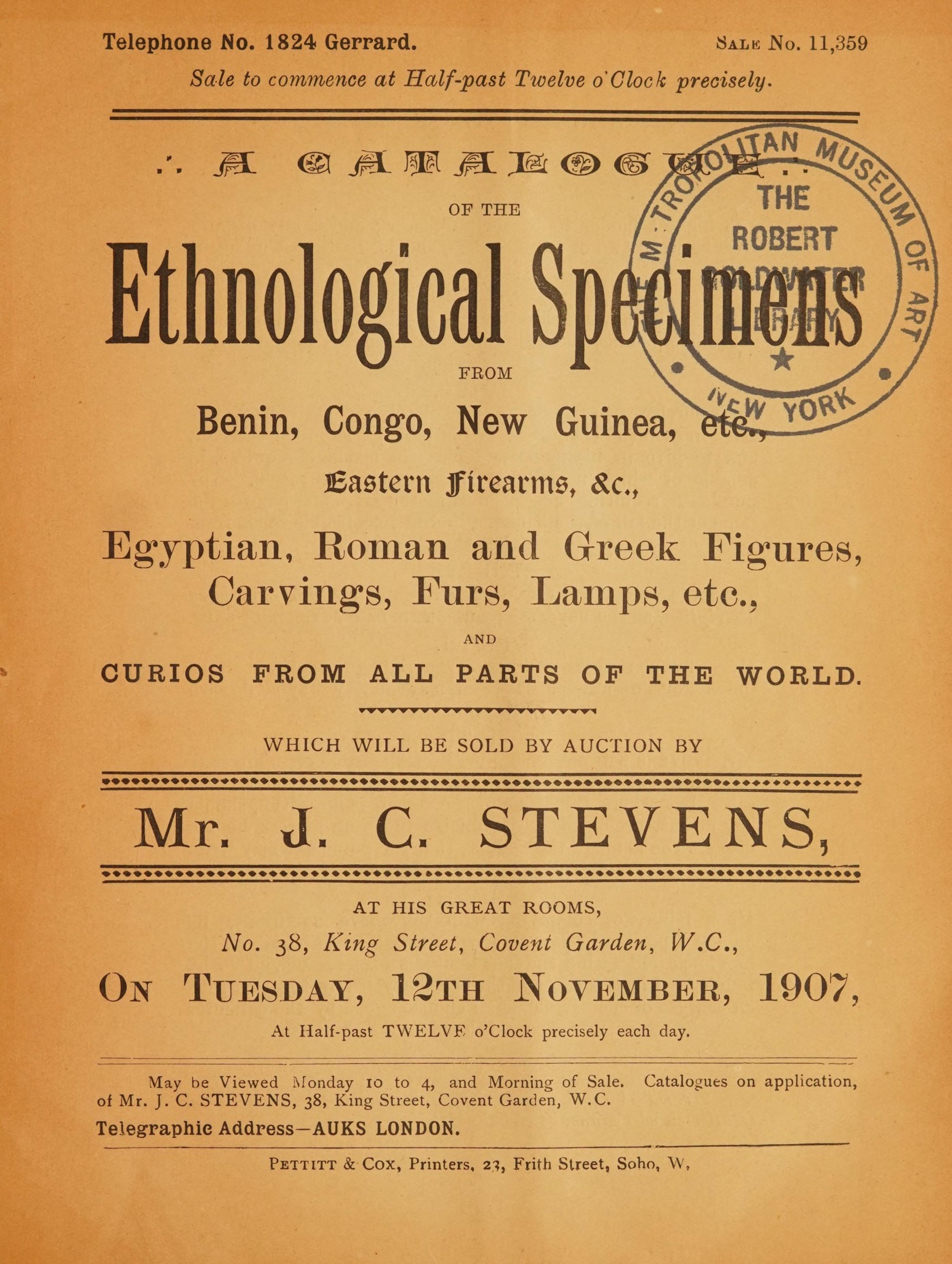

J.C. Stevens. A catalogue of the ethnological specimens from Benin, Congo, New Guinea... : Auction in Paris, November 12, 1907 (London: J.C. Stevens, 1907)

I decided to pull any catalog with the word Benin in the title to be assessed. I examined each catalog to see if it did, in fact, contain lots for Benin artworks. If it did, I flagged it for digitization. If it did not, the catalog went back into circulation. While working through the initial batch identified by the keyword “Benin,” I skimmed through the titles and other information in the catalogs and started noticing several frequently used words and made note of them. Many of the oldest catalogs used language that is considered outdated or outright offensive today. For example, the oldest catalog, dating to August of 1899, is titled “Catalogue of Ethnological Specimens…”. “Ethnological” and “ethnographic” and their various forms ended up becoming some of my keywords. This process produced a few false leads, but ultimately I was able to come up with a list of keywords that I felt confident in.

There was one keyword that I had high hopes for but that were quickly dashed. The Benin people are also known as the Edo people. I attempted to perform a search for Edo and was (probably unsurprisingly) met exclusively with catalogs about Japanese art. I had to let that one go.

W. D. Webster. Catalogue of ethnological specimens. European and Eastern arms & armour. Prehistoric and other curiosities. On sale by W.D. Webster: Auction in London, February, 1900, volume 24 (London: W. D. Webster, 1900)

I ended up with a total of five keywords of varying degrees of effectiveness, including the following and their derivatives: Benin, African (afri*), ethnologic/ethnographic (ethno*), primitive (primi*), and nègre. Ultimately, my methodology landed on pulling any catalog found by searching “Benin,” while any catalog that was found using the other keywords had to match at least two. For example, if a catalog appeared in a keyword search for “Afri*,” it also had to appear in a keyword search for either “ethno*,” “primi*,” or “nègre” to be pulled.

I wanted to cast as wide a net as possible to ensure I got good results. For this reason, I used the asterisk (*) to shorten each keyword to its root. The asterisk acts as a wildcard and enables you to find more results with the same keywords. For example, searching “ethnographic” will only return results for that exact word. Searching for “ethno*” will return results for ethnographical, ethnographic, ethnological, ethnology, etc.

In the end, I was able to identify forty-seven additional catalogs to contribute to the Digital Benin platform. We sent them to our partners at the Internet Archive for digitization, and upon their return collated them to make the collection easy to search in our online catalog through a keyword search for “Digital Benin Project.” We went on to distribute the MARC record set to GitHub so that other institutions can easily use the catalogs. Finally, we brought all of this information together to share with Digital Benin.

Once they had the digitized catalogs, Digital Benin uploaded the files to the organization’s Archive. They were also able to identify many specific objects from within the catalogs. I am proud that we were able to contribute to this project, and I feel lucky to have been given this opportunity and to have learned so much in the process.