The Museum’s Institutional Diversity, Inclusion, and Equal Access Policy Statement asserts that the principles of accessibility “apply to all aspects of The Met’s operations, across all categories of individuals.” Watson Library’s activities are no exception. As assistant manager of e-resources, I focus on the accessibility of Watson Library’s electronic collections.

Efforts to provide accessible resources and services are not only a moral imperative but also legal and professional mandates, as delineated in the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA), Sections 504 and 508 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (the latter of which is specific to electronic information), and the American Library Association’s (ALA) Library Services for People with Disabilities Policy. The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) is an international organization that provides practical guidance and standards for accessible web development in the form of the widely accepted Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). WCAG sets forth extensive and testable criteria for web accessibility.

Accessible electronic collection development begins with the selection of electronic resource platforms and databases that conform to WCAG guidelines. Before the library acquires or subscribes to a new database, its staff and users are typically granted a trial to evaluate the product. With each new resource under consideration, I take concrete steps to assess accessibility and share findings with other library staff.

For instance, I use high contrast mode to confirm that a platform is perceptible to a broad range of users. This feature, built into most operating systems, applies a preset but customizable color theme to the display to accentuate contrast and enhance readability. A resource that is more difficult to navigate in high contrast mode may require increased color contrast or other design modifications. To try out high contrast mode yourself in Windows, press left Alt + left Shift + Print Screen.

In high contrast mode, the Watsonline homepage displays as primarily white text on a black background with menu links in bright yellow. Screenshot by the author

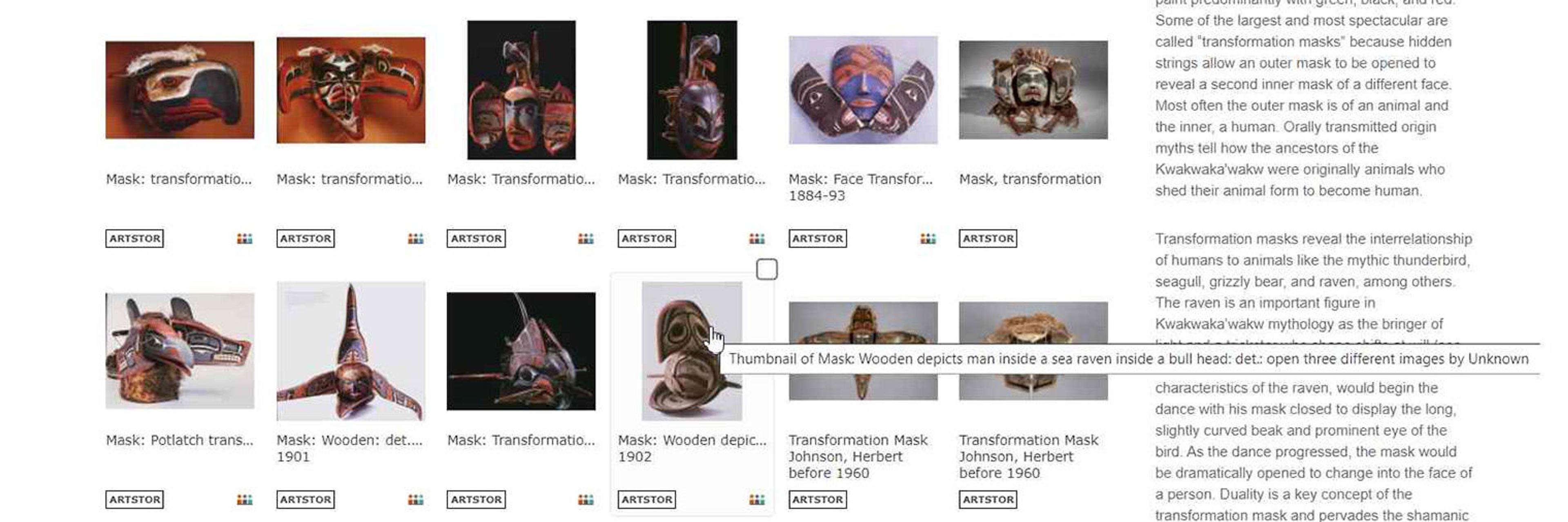

To ensure that the site is accessible to people with visual or hearing impairments, I check that audio and video content is captioned, and that videos incorporate audio description. Likewise, I ensure that images are accompanied by words, whether as alternative or title text—two different means to embed non-visible text in a webpage—or as captions. I do this by examining source code, running a screen reader, or, in the case of title text, hovering the cursor over an image.

In this screenshot of search results from Artstor, the cursor hovers over an image to reveal a balloon that contains title text. The text describes the image as a thumbnail of a wooden mask that depicts a man inside a sea raven inside a bull head. This information could be read aloud to a person with visual impairments. The thumbnail also has descriptive text below. Screenshot by the author

Several browser extensions serve as useful aids for the assessment of database accessibility and have been incorporated into the library’s workflows. These tools are available freely on the Internet and are downloaded for use in Google Chrome on the library’s public computers.

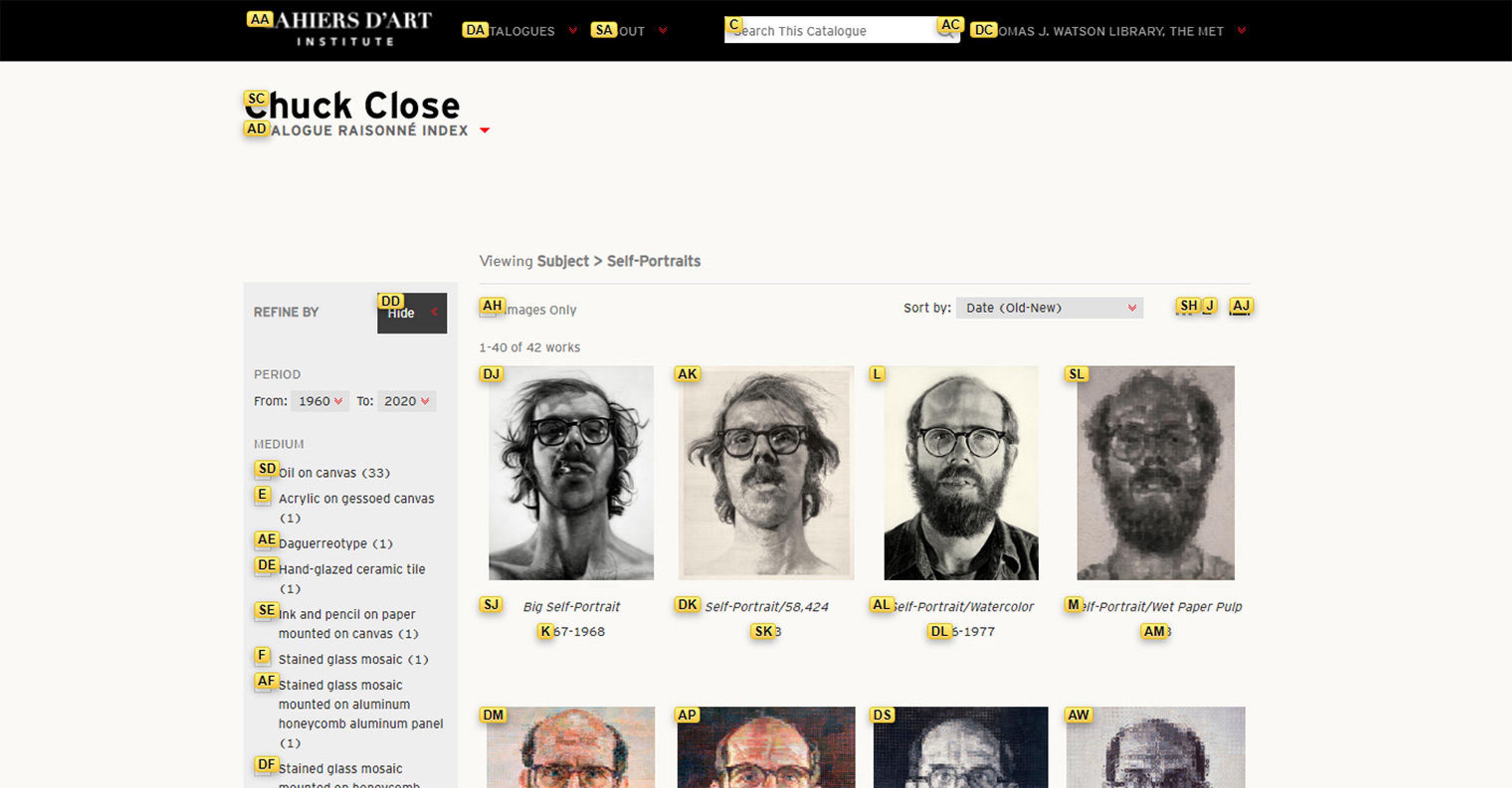

Vimium, for instance, is an extension for Google Chrome that enables a variety of keyboard shortcuts for web navigation without a mouse. One feature of the application allows users to press the “f” key to reveal additional keyboard shortcuts anchored to various locations on the webpage. These shortcuts can be used to click the corresponding locations on the page. Though designed for users with mobility issues, Vimium is also an excellent tool in the database selection process to test whether a user can easily search, retrieve, and use results without a keyboard.

When the Vimium extension is applied in Google Chrome to Chuck Close’s electronic catalogue raisonné in Cahiers d’Art Institute, it reveals anchor points corresponding to keyboard shortcuts. These allow users to navigate the page more easily without the use of a mouse. Screenshot by the author

Another excellent extension to enhance web accessibility is called Helperbird. This application allows users to modify style elements on a webpage in Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, or Microsoft Edge. Some of its features require purchase, but the ability to change fonts, letter and word spacing, paragraph width, and more is free.

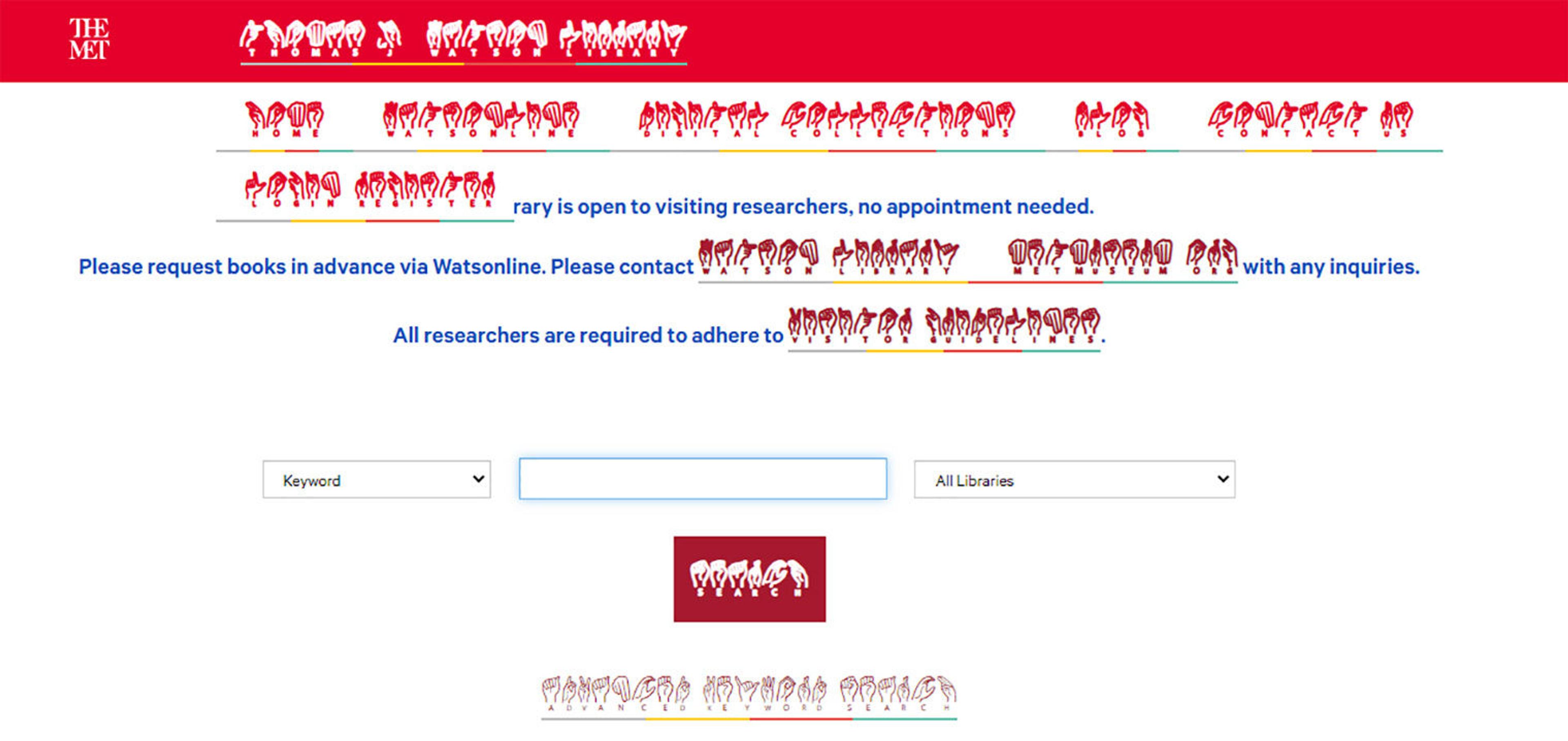

Helperbird allows users to translate text and modify style elements. In this screenshot, the extension is applied to the Watsonline homepage to emphasize links via multicolored underlines and to display text as American Sign Language hand icons. Only a portion of the text has been translated correctly, which suggests that more work needs to be done to increase the accessibility of the catalog. Screenshot by the author

Helperbird incorporates Microsoft’s Immersive Reader, which allows users to highlight, isolate, and customize small bits of text. In this example, I’ve highlighted a selection of words in Gale’s Nineteenth Century Collections Online.

Screenshot by the author

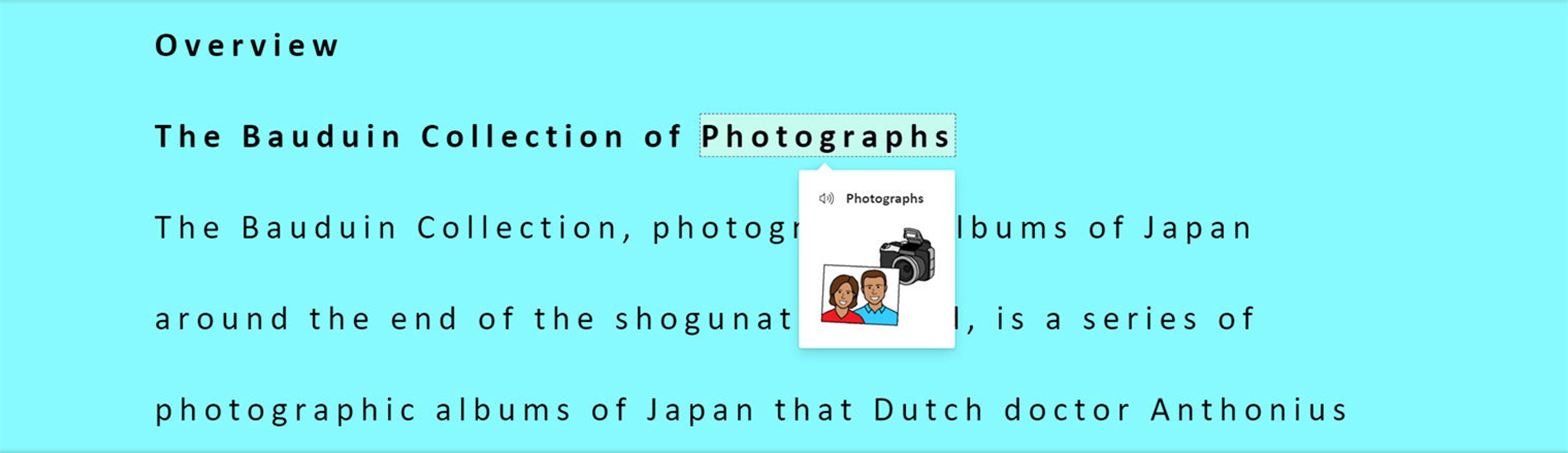

In the Immersive Reader, users can view that text independent of other design elements and objects on the page. Users can prompt the computer to read the passage or individual words aloud, view visual representations of words, translate, and change text size, font, and color.

Screenshot by the author

Like Vimium, Helperbird is designed for use by individuals with disabilities, but is helpful in accessibility assessments because it enables library staff to test whether a database’s display can be adapted without compromising its legibility.

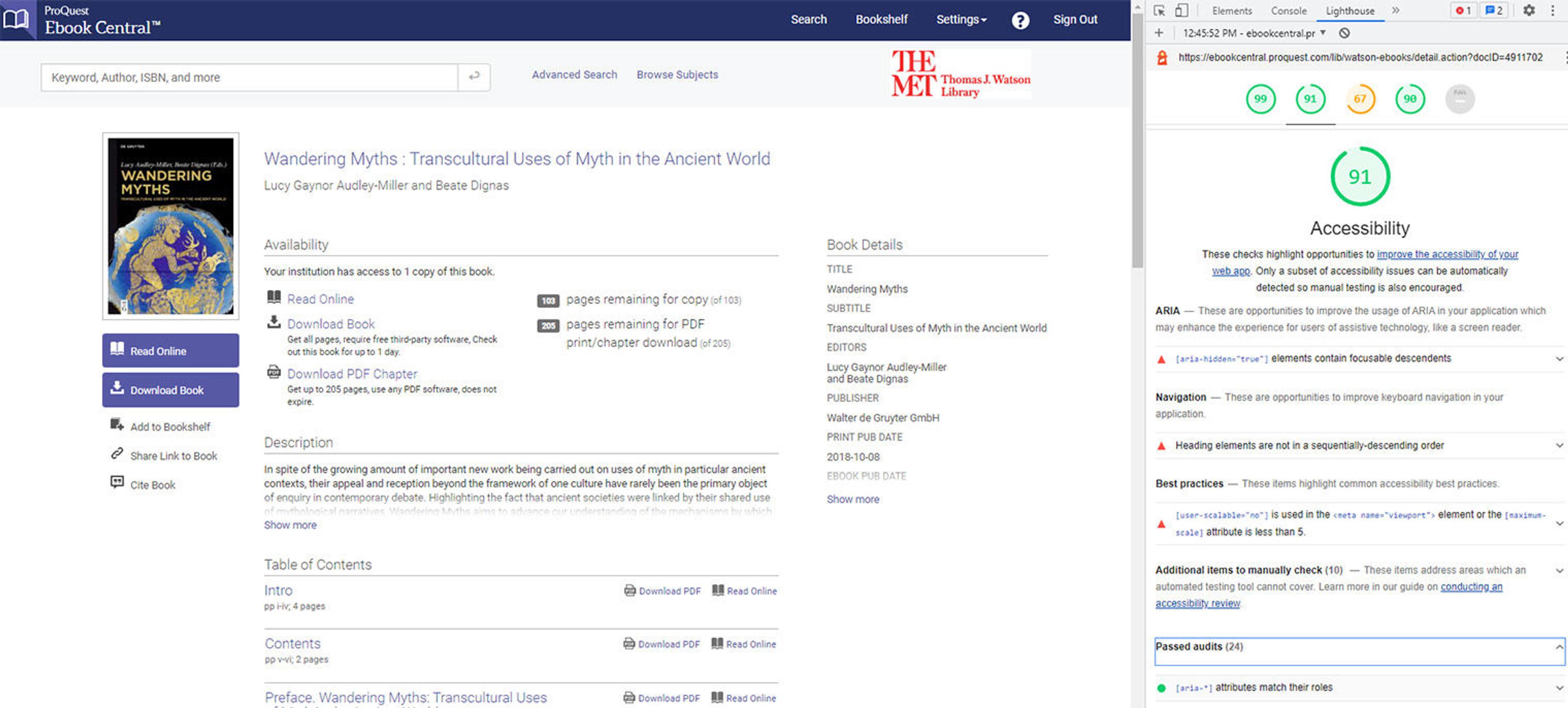

Many browsers and applications are designed to assist web developers and providers in optimizing the accessibility of their sites. These programs perform automated accessibility checks and isolate areas of concern. The accessibility checker built into Google Chrome, for example, is called Lighthouse.

Lighthouse performs an automated accessibility check on a webpage in ProQuest Ebook Central. Screenshot by the author

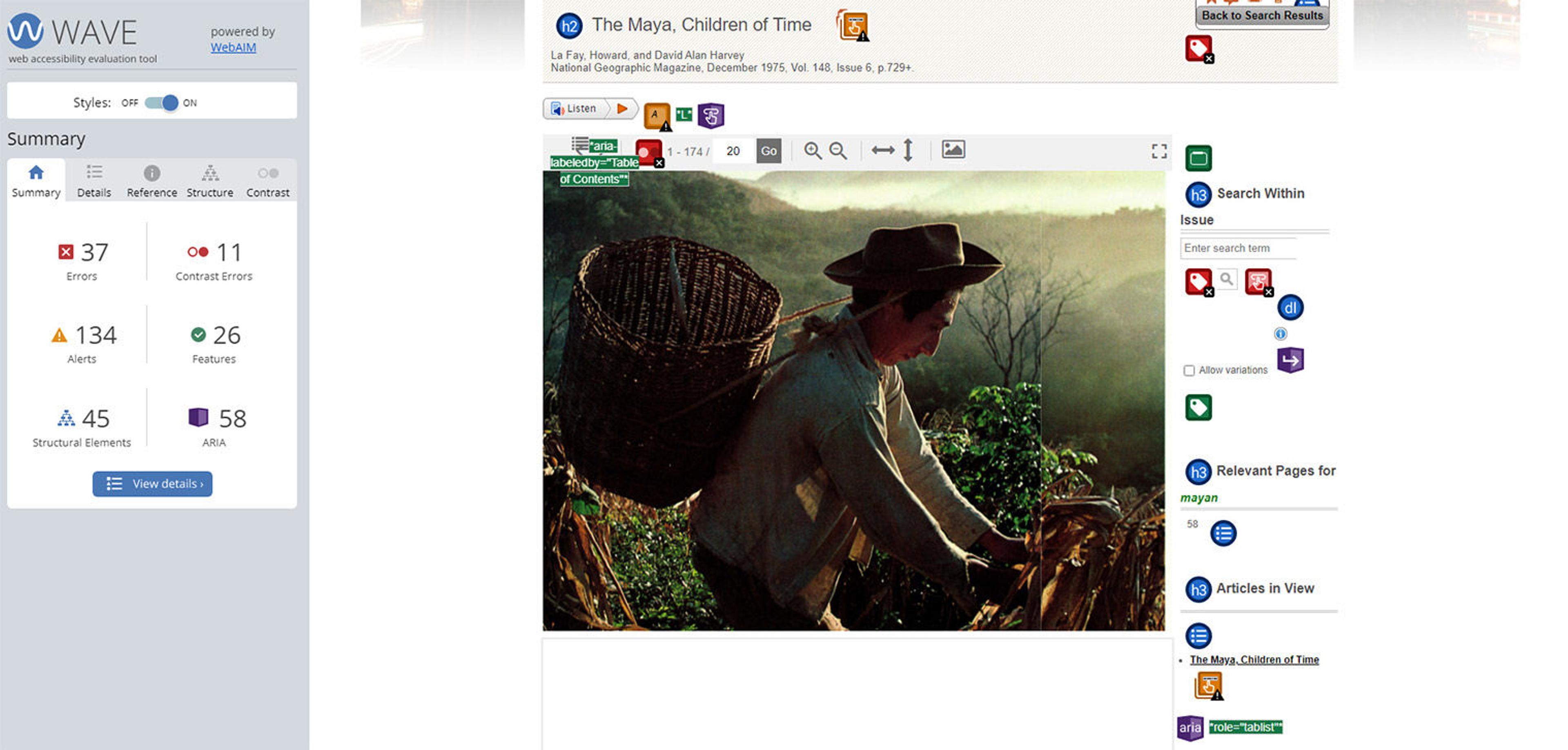

Watson Library uses WebAIM’s WAVE Web Accessibility Evaluation Tool, which provides a more detailed automated breakdown of potential accessibility issues. In this image, I’ve used WAVE to identify possible problems with a webpage from National Geographic Virtual Library.

WAVE flags potential issues in National Geographic Virtual Library as square and circular icons of various colors dotted across the display. These are indexed as errors, alerts, features, and structural elements in the column at left. A webpage that has several flags is not necessarily inaccessible. Screenshot by the author

WAVE output can get granular and complicated, but it provides a general sense of the problems that may need to be addressed. An overwhelming number of issue flags may be a sign that the site developers have not adequately considered accessibility and that the product should not be acquired. Alternatively, WAVE might provide information that the library can bring to the vendor and suggest they implement.

While the library evaluates accessibility on its own, we expect that the vendors and publishers of the databases we work with do the same. We have recently begun to request and internally archive Accessibility Conformance Reports (ACRs)—a detailed form by which publishers document the conformance of their platforms with WCAG, Section 508, and/or a European standard known as EN 301 549—from our database providers. The accessibility documentation project holds the vendors and publishers that we work with, as well as ourselves, accountable. We have urged publishers that do not maintain sufficient accessibility documentation to address the subject and have clearly established that accessibility is one of our priorities.

Watson Library is committed to accessibility, but there is still much work to be done by electronic publishers and by the library. The library has always considered how best to provide resources to our patrons but has only recently begun to formalize a set of procedures around accessibility. We hope that these practices will serve as a foundation for the future, adaptable to the knowledge and input we gather over time. We welcome all feedback, concerns, and questions about electronic resource accessibility at watson.library@metmuseum.org.