For thirty million years the Nile has been flowing from Lake Tana in the Ethiopian highlands, through Sudan, where the Blue Nile meets the White Nile in Khartoum, through the Nubian desert, past Abu Simbel, Aswan, past Luxor, via Cairo, and finally emptying out of the delta of Alexandria into the Mediterranean. These waters gave rise to all of ancient Egypt, the pharaohs, the kingdoms, and the agriculture. The silt and soil of Ethiopia fed the artists, sculptors, priests, slaves, and pharaohs who created the wealth of ancient Egyptian art. The connection between Lake Tana, not far from where my grandmother is from, and ancient Egypt runs deep.

Hailu Mergia & The Walias Band, photo courtesy of Hailu Mergia and Awesome Tapes From Africa

I was born the child of Africanists of the 1960s. In the smoke-filled bars, clubs, and hotels of Addis Ababa gathered modernists, revolutionaries, socialists, activists, and futurists during the height of the belle époque Ethiopian jazz scene. Whether to the sound of the Walias at the Addis Ababa Hilton or the funkier Dahlak Band at the Ghion Hotel, Mulatu Astatke, Getatchew Mekuria, and others created what became the soundtrack of radical imagination, development, and modernization in Ethiopia and across the continent.

Enta Omri performing in Egypt

North of us, in Cairo, Umm Kulthum’s voice, kerchief, and bosom inspired audiences and made them swoon, while Omar Khorshid and his magical guitar serenaded us with love and revolution through Cairo theaters, the radio waves, and the LPs played at home. Like the waters that have bound us over millennia, the music of Egypt and Ethiopia ricocheted back and forth as psycho-funky reverberations of the new postcolonial Africa. Cairo, Khartoum, and Addis are bound by the Nile waters, but also as historic sources of love, art, music, empire, and revolution.

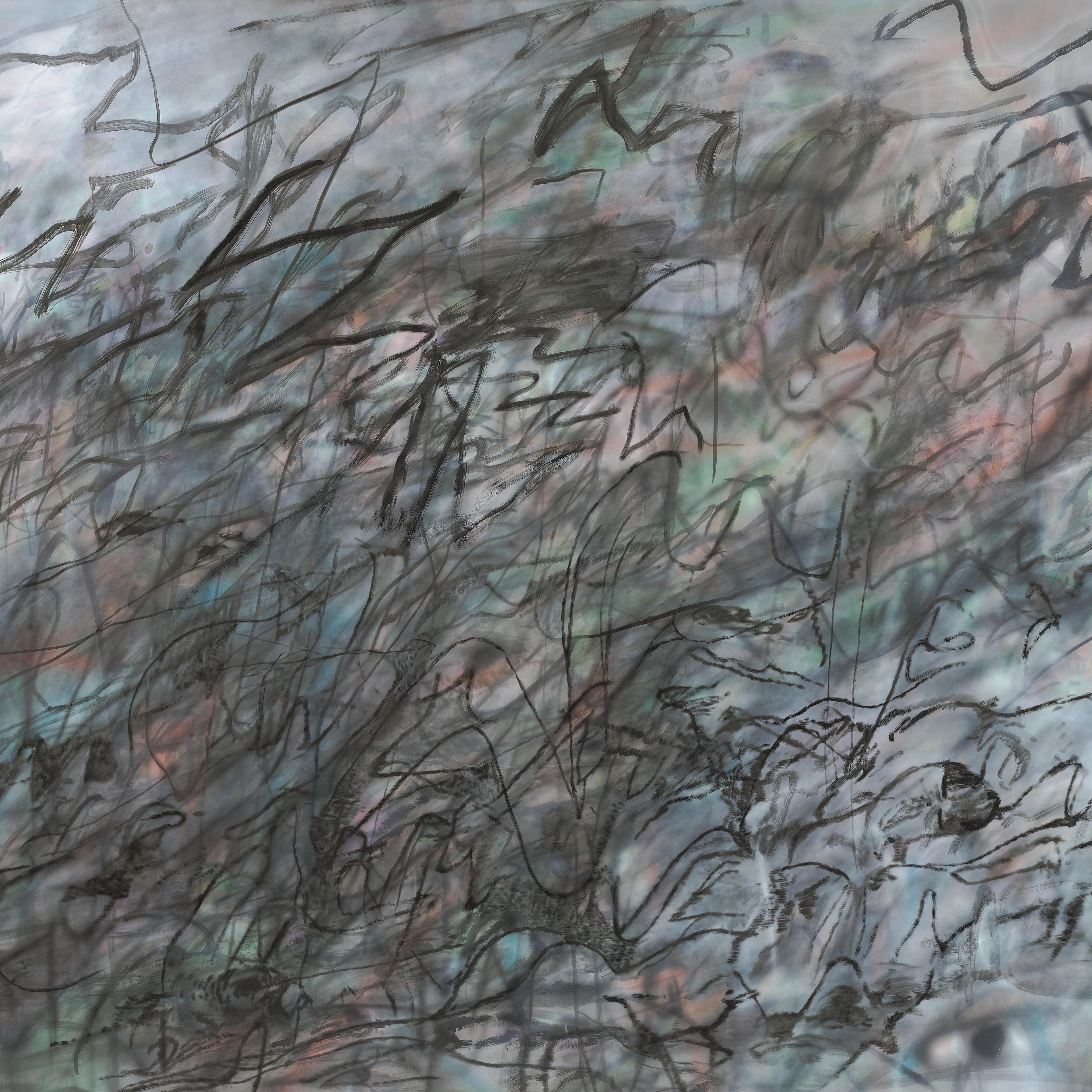

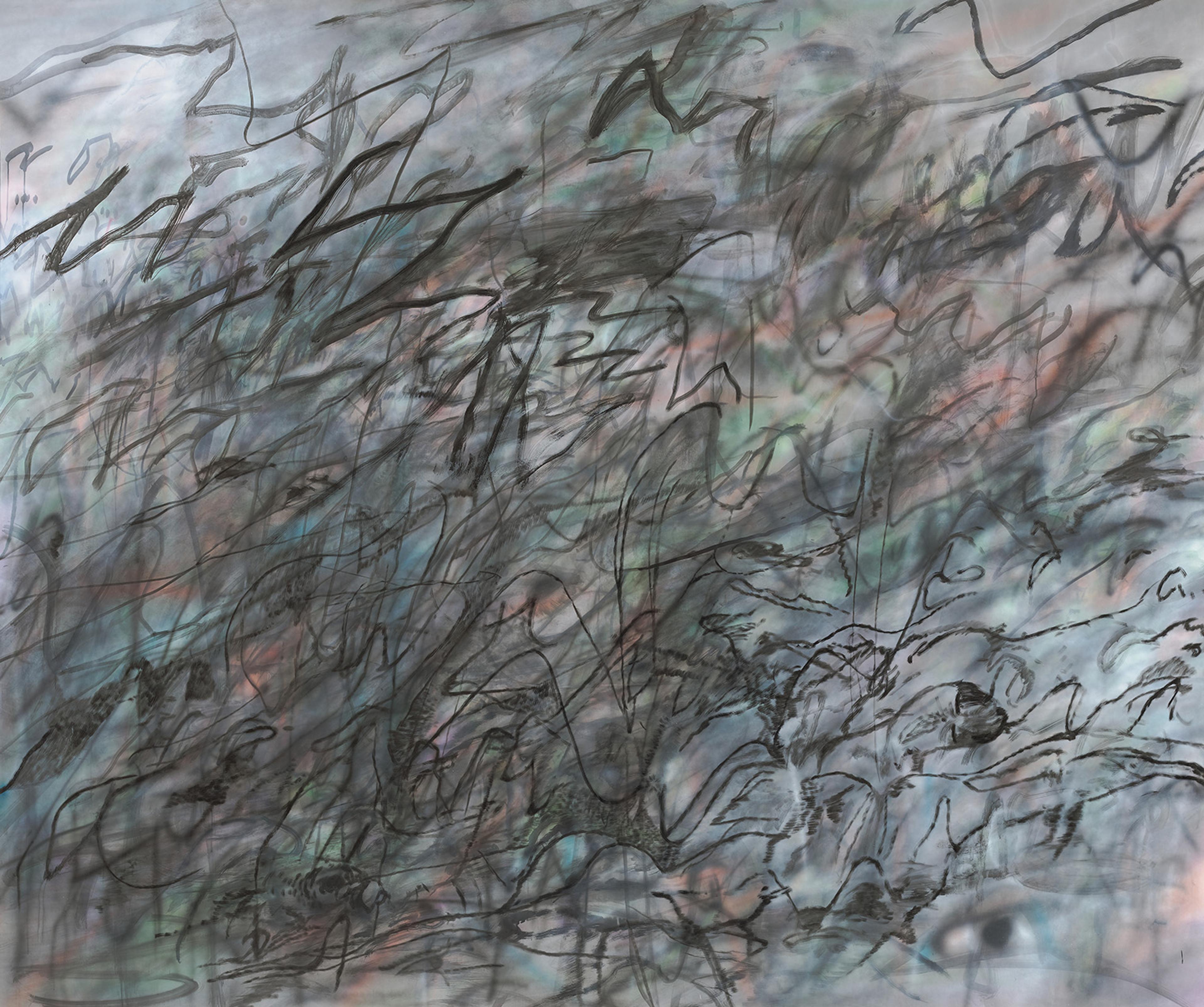

Julie Mehretu (1970). Stelae 3 (Bardu), 2016. Ink and acrylic on canvas, 10 × 12 ft. (304.8 × 365.8 cm). Collection of Lisa and Steven Tananbaum

Visiting from Zimbabwe (where we were living in 1984–85) in its early postrevolutionary days, I saw the pyramids of Giza for the first time when I was fourteen and became completely enchanted with ancient Egypt. Not only for the astounding inventions of these ancient Africans that preceded ancient Greece, Rome, and so on, but also for the experiences I had in my encounters with the work. I have returned many times since, to study at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (one of my favorite museums in the world), the Temple of Karnak in Luxor, the Valley of the Kings and Queens in the desert, and the pyramids of Dahshur. But also, more times than I can count, I have studied the Egyptian collections of the Neues Museum in Berlin and the British Museum in London.

It felt as if that person from over five thousand years ago had just taken a breath with me; it gave me goose bumps.

I vividly remember a sculpted head at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo that felt as if it was inhaling through its nose, while I was standing in front of it. That experience expanded my understanding and altered my perception of art. It felt as if that person from over five thousand years ago had just taken a breath with me; it gave me goose bumps. An artist, thousands of years ago, had made black granite stone breathe, and breathe with me.

Much is misunderstood about ancient Egyptian sculptures. These are not approximate, stylized iconographic symbolic images—rather, they are observationally descriptive and vivid portraiture. Each piece, with its specific features—wide ears, elongated chin, broad cheekbones, narrow face, severe expression or bright smile, thin or full lips—is unique in its likeness. Braided heads and sculpted Afros that look like the heads of my aunts, great-aunts, my grandmother, and great-grandmother.

Julie Mehretu's Grandmother and Great-Aunts in Ethiopia. Courtesy of the artist.

We can see Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Hatshepsut, Ramesses II, Thutmose III, and Amenhotep III as distinct individuals. These Nubian and Asiatic Africans of immense power, capability, creativity, and beauty are our collective historic humanity. Whether in the poems of Sappho or the eyes of Hatshepsut or the slightly parted mouth of Akhenaten, we feel them empathetically, and through them, we breathe, their breath that, in the words of Adrienne Edwards, “exalts the real.”

This essay is adapted from the catalogue Flight into Egypt: Black Artists and Ancient Egypt 1876–Now, which accompanies an exhibition on view through February 17, 2025.