This article marks the seventh International Provenance Research Day, held annually on the second Wednesday of April. Below you will find five provenance case studies for select recent acquisitions authored by provenance researchers across the Museum. The authors are partners in The Met’s cultural property initiatives that includes an in-depth review of the history of artworks and cultural artifacts throughout the Museum’s collections. Each story demonstrates the varied and complex nature of provenance research at The Met, from antiquities to modern art, and the contribution that this scholarship makes to our understanding of the artworks themselves.

Canosan Head-Vase

In 2024, the Department of Greek and Roman art acquired a Hellenistic vase produced around Canosa (ancient Kanousion), a town in Apulia in southern Italy. Shaped as a woman’s head with two smaller female heads emerging from acanthus leaves, it was also topped with a clay statuette of a woman that served as support for a tall handle at the back. Traces of polychromy—red, green, and pink pigments applied over the white slip—help us to imagine how stunning it once looked. However, it was not a properly functional vessel, as it lacks a bottom and a mouth; instead, it belongs to a widespread category of objects intended exclusively as grave offerings, as most Canosan vessels were.

Polychrome terracotta head vase, ca. 3rd–2nd century BCE. Canosan, Puglia. Hellenistic. Terracotta, 14 3/8 x 8 3/8 x 9 1/2 in. (36.4 x 21.2 x 23.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Marguerite and Frank A. Cosgrove Jr. Fund, 2024 (2024.352)

The head-vase came to The Met from the estate of Philip M. Pearlstein (1924–2022), a renowned American painter.[1] Many of his artworks—namely his portraits, nudes, and arrangements of objects—feature seemingly random items, including antiquities. A closer look at the photographs of his residence and studio reveals that the artist collected all sorts of artifacts: there are Greek and Etruscan vases, antique textiles, duck decoys, Godzilla toys, marionettes from around the world, and ancient American antiquities, among others. Incidentally, the Canosan head-vase can be spotted on a shelf in Pearlstein’s atelier in a photograph from this charming account of the artist’s work on a portrait of Helene Verin.

The head-vase on a shelf in the approximate center of this photograph from Philip Pearlstein’s studio. Photo courtesy of Helene Verin

The Canosan head-vase’s history of ownership can be reconstructed from its discovery to now, albeit with some lacunae. In 1895, on the property of Savino Scocchera in Mandorleto Grotticelle, slightly east of Canosa, the local workmen discovered two hypogea-tombs filled with grave goods, including multiple vases.[2] One tomb (so-called Tomb A) contained the burials of three warriors, whereas the other (so-called Tomb B), where the head-vase came from, reportedly contained a burial of a woman.[3] The contents of the tombs were removed and placed in the house of the land owner Sgn. Scocchera, where an antiquarian Maximilian Mayer examined them soon after their discovery.[4] Since the plentiful grave goods from both tombs were dispersed by the landowner shortly thereafter, we still do not have a reliable list of all the objects found in both tombs.

It seems that most vases, including the head-vase, were sold by Savino Scocchera to the brothers Cesare and Ercole Canessa, antiquity dealers based in Naples, Paris, and New York. Sometime prior to 1922, the head-vase ended up in the hands of Joseph Chmielowski, an obscure collector and dealer, who brought his collection of antiquities to New York City. This collection was mostly assembled from the objects excavated and bought prior to 1917 in the south of the Russian Empire, modern-day Ukraine, in the vicinity of Odesa and in Crimea. At the moment, we lack any information on exactly when and how Joseph Chmielowski acquired the Canosan head-vase; it is noteworthy, however, that he also had several smaller vases from the Scocchera tomb in his collection, which was offered for sale in February 1922 through the American Art Galleries in New York.[5]

The newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst purchased the head-vase, mistakenly labeled as “from Olbia, in South Russia.” In the late 1930s, facing grave financial difficulties, Hearst was forced to sell off large parts of his massive collection. The Hammer Gallery in New York organized the Hearst sale through Gimbel Brothers Department Store in 1941. It turns out that one could go bargain hunting for antiquities at Gimbels at the time, whereas the more expensive objects were sold at Saks Fifth Avenue.[6] For now, it remains unknown who purchased that Canosan head-vase at Gimbels; we next encounter it in 1978, when it was purchased by Pearlstein from Edward E. Merrin Gallery in New York.

Left: Terracotta funnel-jar. 19 1/8 in. (48.4 cm). (06.1021.248a, b). Right: Terracotta two-handled vase. 30 3/4 in. (78.1 cm). (06.1021.246a, b). Both late 4th–early 3rd century BCE. Greek, South Italian, Apulian, Canosan. Early Hellenistic. Terracotta. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1906

In 1906, The Metropolitan Museum of Art purchased an extensive collection of Greek vases from the Canessa brothers. Among them there were several vases that also came from Tomb B, discovered in 1895, such as a terracotta funnel-jar; terracotta two-handled vase; and several terracotta reliefs, including a woman, a youth, and a rider, from funnel-jars. The head-vase rejoined them 130 years later.

Statuette of the Virgin and Child

Provenance research often sends researchers down complex paths full of twists and turns, and coincidence often plays an active role in successful research on an artwork's history. In 2021, the Department of Medieval Art and The Cloisters received a bequest from Nanette Rodney Kelekian (1926–2020), a collector-dealer and an important patron, volunteer, and friend of The Met. Nanette’s grandfather, Dikran Garabed Kelekian (1876–1951), and her father, Charles Dikran Kelekian (1900–1982), were notable art dealers during much of the twentieth century.[7] Through the years, Nanette Kelekian had donated many works of art to various curatorial departments at the Museum.

Left: Panel with Warrior Resting, 4th–6th century. Egypt. Late Roman/Early Byzantine. Bone, 3 1/8 x 1 5/8 in. (8 x 4 cm). (2021.37.5). Center: Head of a Bearded King, ca. 14th century. French. White marble, traces of red paint and gilding, 2 3/8 x 1 3/4 in. (6 x 4.3 cm). (2021.37.14). Right: Pharmacy Jar, 14th century. Valencia, Spain. Spanish. Tin glazed earthenware (copper and manganese oxides), 9 1/4 x 3 3/4 in. (23.5 x 9.5 cm). (2021.37.19). All The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Nanette B. Kelekian, 2020

The twenty-four works of art that Nanette Kelekian bequeathed in 2021 included Late Roman bone panels that decorated domestic furnishings, a fourteenth-century stone head of a bearded king, and a Spanish tin-glazed earthenware jar, among others works. One of the objects from the gift is a boxwood sculpture of Virgin Mary and Child in which the baby Jesus carries a basket, a rather unusual attribute.[8] Dated to the sixteenth century and produced in a French or Netherlandish workshop, the sculpture is carved completely in the round. Its size and the existence of a hole drilled into its back suggests it was part of larger work used for personal devotion.

Statuette of the Virgin and Child, early 16th century. Franco-Netherlandish. Boxwood, 3 5/8 in. (9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Nanette B. Kelekian, 2020 (2021.37.18)

We only knew that the work had belonged to the Kelekian family for decades and that it was thought to have been purchased from a dealer named “Mohl.” Days after the sculpture’s arrival, I had coincidentally come across a similar name while researching the history of several medieval sculptures in the collection, including a work acquired by the Museum in 1917 from the estate of J. Pierpont Morgan in 1917, a sculpture of Saint George bequeathed to The Met by former Museum president George Blumenthal in 1941, and two late medieval bust reliquaries purchased in the late 1960s and early ’70s respectively.

Left: Reliquary Bust of Saint Balbina, ca. 1520–30. Possibly Belgium. South Netherlandish. Oak, with paint and gilding, and human remains, 17 1/2 x 16 x 6 1/4 in. (44.5 x 40.6 x 15.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Susan Vanderpoel Clark, 1967 (67.155.23). Right: Reliquary Bust of a Female Saint, early 16th century. South Netherlands. South Netherlandish. Oak, painted and gilded, and human remains, 20 1/8 x 14 1/4 x 6 5/8 in. (51.1 x 36.2 x 16.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters Collection, 1976 (1976.89)

The name “Mohl” reminded me of a 1912 sale at auction at Hôtel Drouot in Paris for a Louis Mohl, which included fifteenth- and sixteenth-century sculpture. Images of the bust reliquaries in the 1912 sale made their identification easy. There were no images of the other Met works. Going back to the catalogue, lot 35 described a sculpture of the Virgin and Child that was nine centimeters tall and where the child holds a “corbeille,” or basket. Fortunately, the copy of the auction catalogue I consulted also included the names of the buyers and prices in red ink. For lot 35, the purchaser’s name was Kelekian. With this additional notation, it was clear that the sculpture described in the auction was, indeed, the same work that had just arrived at the Museum. The work’s history from 1912 until its accession into the collection was now complete.

1912 auction catalog for Louis Mohl, showing lot 35 purchased by “Kelekian” on the page at right

But one question remained: Who was Louis Mohl? The auction catalogue stated that the sale took place following Mohl’s death. One Jean Louis Mohl—who was born in Frankfurt, Germany, in about 1845 and died in Paris on February 29, 1912—seemed like a suitable lead. Existing documentation available on Ancestry.com identified his address on the Boulevard Flandrin and described him as unmarried.[9] After more digging, I found that a Louis Mohl served as the secretary for Gustave de Rothschild (1829–1911), a member of the French branch of the renowned Rothschild banking family, many of whom were also notable art collectors.[10] It appears likely that this is the same Louis Mohl who owned The Met’s five sculptures. As secretary for Gustave de Rothschild, Mohl would have had the access and opportunity to collect works of art. Today, works from Mohl’s collection can also be found at Hearst Castle in San Simeon, California.

Sèvres Bowl

This exceptionally large bowl was made in 1850 at the Sèvres factory near Versailles. The provenance of the bowl is intriguing. It was offered to The Met by the London art dealer Amir Mohtashemi, who had bought it at an online auction by Christie’s New York held from March 22 to April 5, 2022. Christie’s listed the Château de La Rochepot in La Rochepot, France, as its previous owner.

Sèvres Manufactory (French, 1740–present). Large ceramic bowl, 1850. Hard-paste porcelain; pâte-sur-pâte, polychrome glaze, and gold, 13 x 32 3/8 in. (33 x 82 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Alexandra Wait, William Wait, and Younghee Kim-Wait Gift and Turkish Centennial Fund, 2024 (2024.409)

We contacted Christie’s and learned that the consigner of the bowl had bought it at a judicial sale by the French Government in October 2021 in Beaune, France, where the entire contents of the Château de La Rochepot had been auctioned off. The government had seized the castle in October 2018 after an investigation into an alleged money laundering and corruption scheme by its then-owner Dmytro Malynowskyi, who had purchased the castle in 2016 in an apparent plot to disappear after faking his own death in his home country of Ukraine.

Château de La Rochepot. Photo courtesy of John Picken, CC BY 2.0

Malynowskyi purchased the castle with all its contents from the prominent Carnot family, who had owned it since 1893, when Cecile Carnot, the wife of the President of the Republic Sadi Carnot, had bought the ruins of the castle. She gifted it to her eldest son, infantry colonel Sadi Carnot (1865–1948), who for twenty-six years conducted a meticulous historical restoration of the building in the spirit of the fifteenth century. The Carnot family subsequently owned the castle until its sale in 2016.

The Sèvres Bowl seen on the table during the court-ordered auction of the castle and its furnishings

We were interested in knowing whether the bowl was in the castle and owned by the Carnot family when Malynowskyi bought it, so we contacted Patricia Besse Realty in Paris, who had brokered the sale of the castle in 2016 and asked if they had any photos of the castle’s interior that might feature the bowl. They responded that they had forwarded our message to the Carnot family. To this date we have not received a reply.

Assyromania

In 2023, the Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art acquired a unique collection of objects illustrating the reception and revival of ancient Assyrian art in modern Europe. The collection includes metal sculpture, ceramics, jewelry, drawings and prints, and books, mostly dating to the nineteenth century, produced mainly but not exclusively in Britain. Objects featuring ancient Mesopotamian imagery began to be used in European decorative arts following the unearthing of Assyrian palaces in northern Iraq in the mid-nineteenth century and the display of Assyrian sculptures in England and France—including some now at The Met.[11]

William Simpson (British, 1823–1899). The Tower of Babel or Birs Nimrud Restored, ca. 1885. Watercolor over graphite, 13 3/4 x 24 1/2 in. (35 x 62 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Henrietta and Christopher McCall Collection, Purchase, Bequest of Henrie Jo Barth, and Museum Acquisitions and Josephine Lois Berger-Nadler Endowment Funds, 2023 (2023.674)

The collection was assembled by Henrietta and Christopher McCall, mostly in the 1990s and 2000s, and kept in their home at Henley-on-Thames, in Oxfordshire, England. Henrietta McCall was a scholar of Assyrian revival and her interest in this material was informed by an academic understanding of its place in the broader reception of ancient art and architecture in early modern Europe. The artworks were acquired at auction sales, fairs, jewelry and antique shops mainly in Britain. Researching the provenance of these objects was slightly unusual for a department focused on ancient art. Moreover, the previous owners had carefully kept documentation regarding most of their purchases that greatly aided provenance research. We are thrilled to be able to follow the wish of the McCalls that their collection remain together and publicly accessible in a museum.

Left: "Nimrod" flower vase, after 1868. Unglazed porcelain (Parian ware), 6 1/2 x 2 3/4 in. (16.5 x 7 cm). (2023.665). Right: Brooch with Assyrian human-headed winged bull, ca. 1873. Gold, enamel, glass, 2 in. (5 cm). 2023 (2023.691). Both British. Victorian. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Henrietta and Christopher McCall Collection, Purchase, Bequest of Henrie Jo Barth, and Museum Acquisitions and Josephine Lois Berger-Nadler Endowment Funds, 2023

Henrietta McCall herself investigated a pair of bronze and slate urns purchased by the McCalls on eBay in 2004, later describing the effort as “a Hollywood mystery.”[12] The urns are large vessels manufactured by the firm of Matifat, examples of which were included as representatives of French metalworking at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London. The decoration was inspired by scenes of hunting and war from the Assyrian palace reliefs. In the course of restoration work, conservator Pippa Pearce found a letter in one of the urns that revealed a clue about their ownership history. In the early twentieth century, the urns belonged to Hollywood actor W. C. Fields (1880–1946) and were sold after his death on behalf of his partner, Carlotta Monti (1907–1993), who was the author of the hidden letter. She reported that Fields “brought them with him from Paris in 1902.” Based on her research, however, Henrietta McCall suggested another possible source: Fields may have obtained them from American film director D. W. Griffith (1875–1948) in the late 1930s. Extensive research was conducted for Griffith’s epic 1916 film Intolerance, and the urns may have been collected as reference material for the section set in Babylon. Fields and Griffith worked together in the 1920s and kept in touch until the early 1940s, at which point Fields might have obtained the urns.

Urn with Assyrian scenes, 1851. French. Victorian. Slate, bronze, 15 3/4 in. x 15 in. (40 x 38 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Henrietta and Christopher McCall Collection, Purchase, Bequest of Henrie Jo Barth, and Museum Acquisitions and Josephine Lois Berger-Nadler Endowment Funds, 2023 (2023.650 and 2023.651)

Kurt Schwitters in the Janis Gift

In 2024, the Modern and Contemporary Art department acquired forty-eight works from the estate of Maria and Conrad Janis. Most of the works passed through the legendary New York gallery of Sidney Janis, Conrad’s father, although a number reflect Conrad Janis’s independent collecting practice. The earliest work in the gift is a 1914 drawing by Piet Mondrian and the most recent is a 2006 inkjet print mounted on panel by Robert Rauschenberg. Seventeen works by the German artist, Kurt Schwitters, comprise the largest holding of a single artist.

Sidney Janis opened his gallery in 1948 following his retirement as a shirt manufacturer; having already accumulated a private art collection, he chose to start his new business doing “something [he] loved.”[13] Although best known for championing Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art, Janis organized four Schwitters exhibitions in 1952, 1956, 1959, and 1962, all of which included works now in The Met collection.

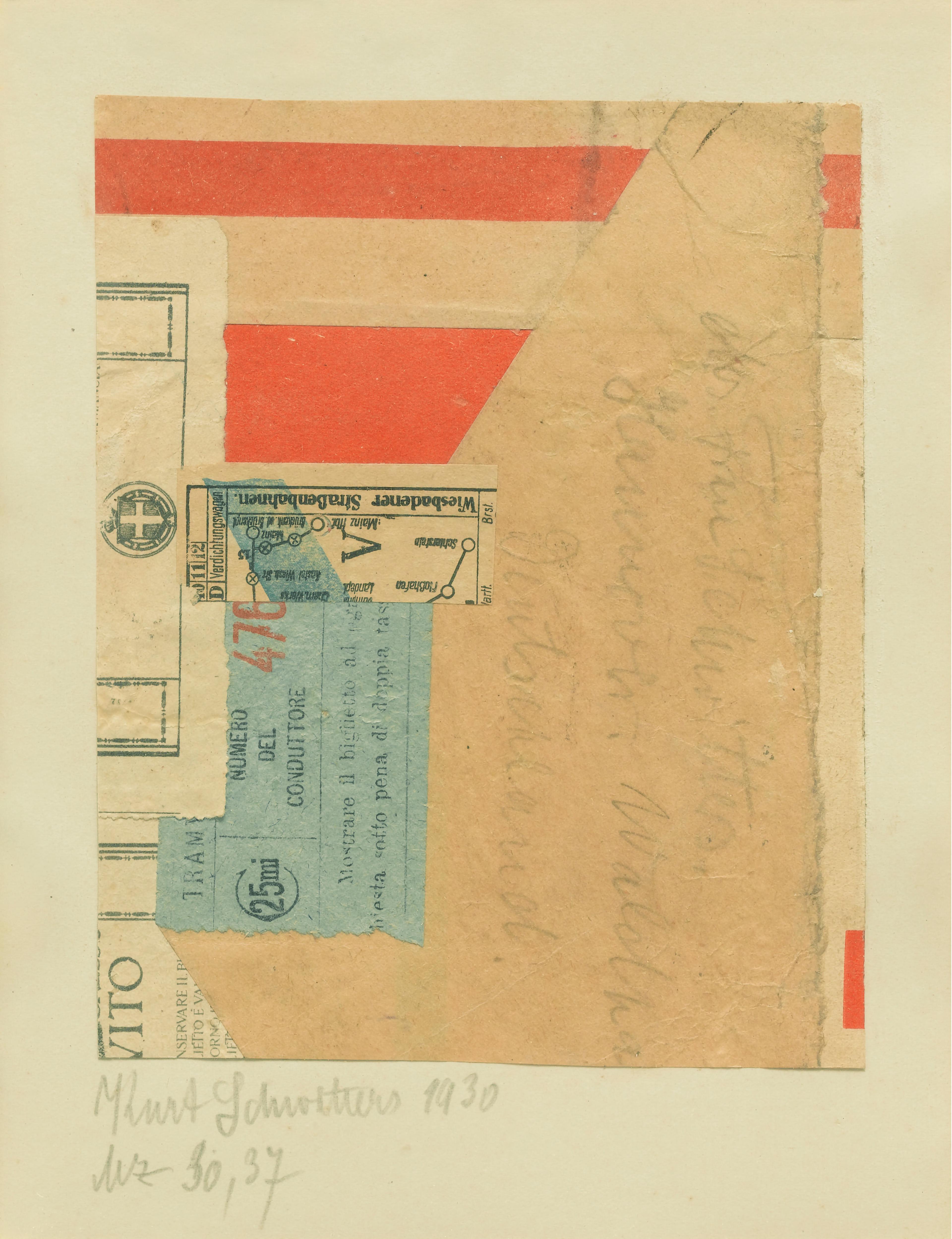

Kurt Schwitters (German, 1887–1948). Mz 30,37, 1930. Collage, paper on paper, 6 3/4 × 5 1/4 in. (17.1 × 13.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Maria and Conrad Janis Estate, 2024 (2024.88.32) © 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo courtesy of Pace Gallery

Except for one late painting, the Janis gift of Schwitters’ works are all collages, which the artist began creating in 1918 when he met and befriended members of the Berlin Dada group. Sharing the Dada embrace of chance and spontaneity, Schwitters applied the invented term “Merz” to his new works that used ephemera, discarded papers, and found objects to express the unification of art and daily life. For example, Mz 30,37 (1930) includes fragments of a map of the Wiesbaden tram system, an Italian tram ticket, and an envelope with the artist’s handwritten return address.

In 1937, Schwitters was targeted by the Nazis as a “degenerate artist.” He fled to Norway, closely following his son Ernst. When Germany invaded Norway in 1940, father and son escaped to England via Scotland, and after being held in different internment camps, settled in London. In the last years of his life, Schwitters struggled financially; although he sold some paintings, he relied on his friend Walter Dux, a fellow emigré from Hanover in London, for monetary support. Two of The Met collages were gifts from the artist to Dux. When Kurt Schwitters died in 1948, Ernst, who had returned to Norway, inherited the majority of his works. Sidney Janis once commented that shortly after Schwitters’s death, he could buy a small Schwitters collage for ten dollars.[14]

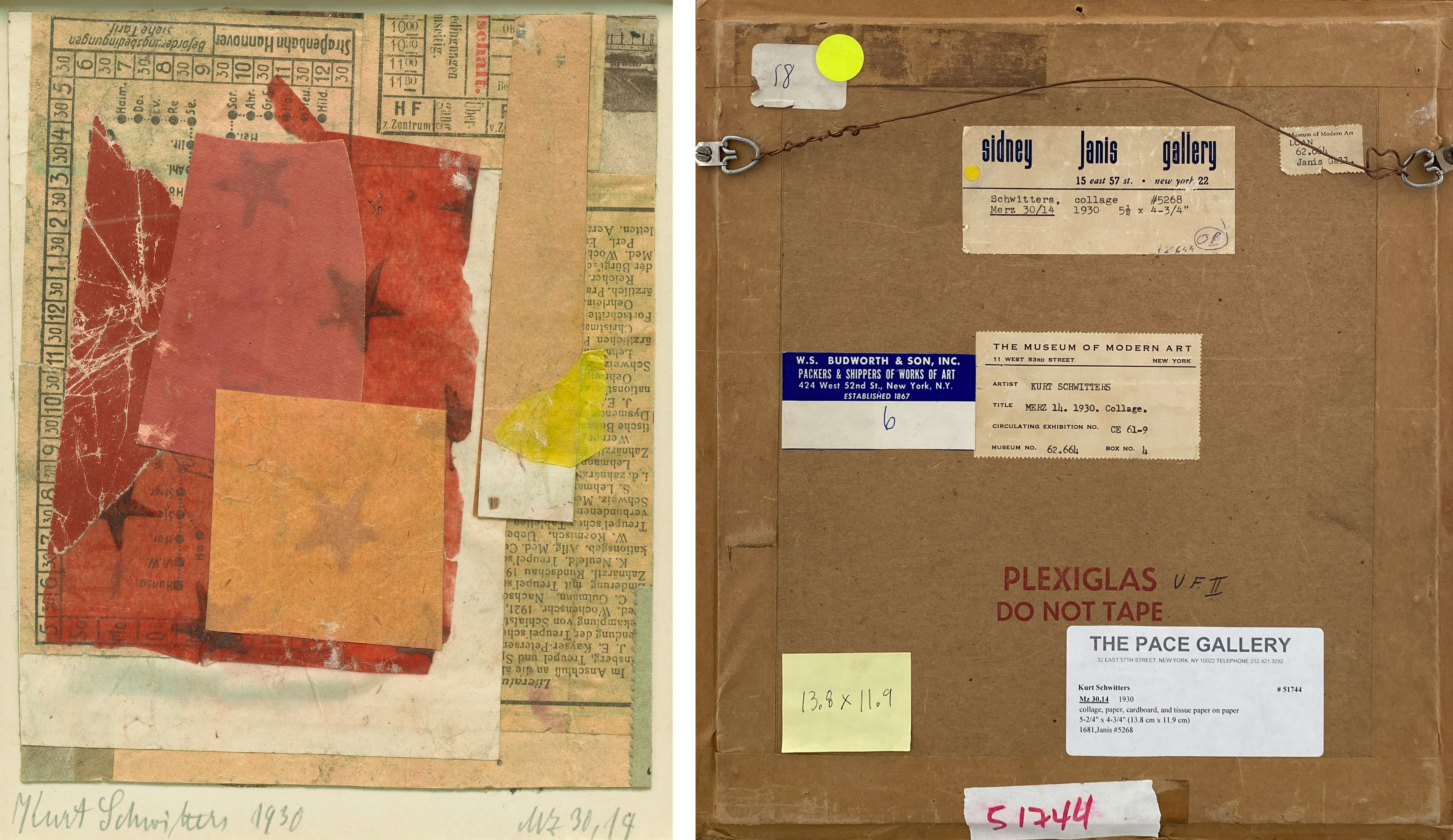

Kurt Schwitters (German, 1887–1948). Mz 30,14, 1930 and verso. Collage, paper, cardboard, and tissue paper on paper, 6 × 4 7/8 in. (15.2 × 12.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Maria and Conrad Janis Estate, 2024 (2024.88.40) © 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo courtesy of Kerry Ryan McFate, Pace Gallery

Ernst Schwitters sold a number of his father’s works in the 1950s, as can be seen in the provenance for about half of the Schwitters works in the Janis gift. A list provided to The Met from the Kurt Schwitters Archive shows that Ernst sold several at the time of Schwitters’s first posthumous retrospective held at the Kestner Gesellschaft in 1956. Prior to the opening of his own gallery, in 1956–57, the Hanover dealer Hans Brockstedt purchased about twenty works, which he soon sold to Sidney Janis. Cross referencing Ernst Schwitters’s list, later correspondence with the Galerie Brockstedt, and Sidney Janis’s gallery index cards led to definitively confirming this chain of ownership for Mz 30,14 (1930). Because Ernst Schwitters did not consistently transfer his assigned inventory numbers to later archive cards, the provenance for Ohne Titel (wird angezundet) (Untitled [Will Be Lit]) (1926) reads “possibly” sold by the artist’s estate.

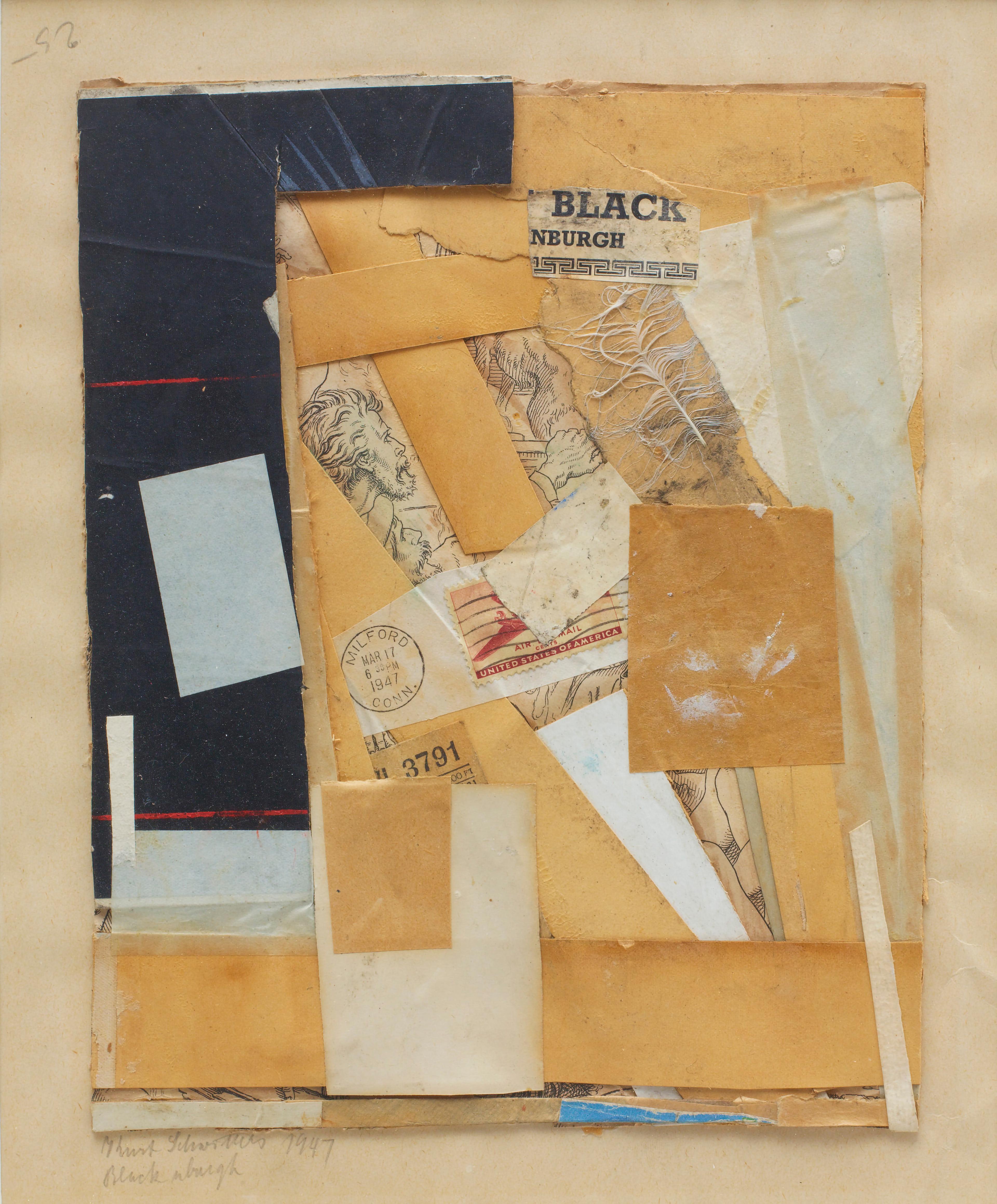

Tracing the provenance of the recent Schwitters acquisitions, together with the three Schwitters collages already owned by The Met, reveals different trajectories for the works once they left the artist’s studio. For example, Black Nburgh (1947) made a circuitous route from Sidney to Conrad Janis. After being sold by Sidney Janis to the well-known collector G. David Thompson of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, it was then owned by a succession of European private collectors and dealers. In 2013, it was purchased at auction at Sotheby’s, London, by Pace Gallery, New York, who in turn sold it to Conrad Janis. An early collage was sold in 1953 by Sidney Janis to the Chicago collector Muriel Kallis Steinberg, who gave it to The Met in 2006.

Kurt Schwitters (German, 1887–1948). Black Nburgh, 1947. Collage on paper laid down on the artist's mount, 11 1/2 × 9 1/2 in. (29.2 × 24.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Maria and Conrad Janis Estate, 2024 (2024.88.34) © 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo courtesy of Kerry Ryan McFate, Pace Gallery

Besides promoting Schwitters collages in solo exhibitions, Janis included them in multiple group exhibitions. An overview of the Janis gift provides insight into the market for Schwitters’s oeuvre during the 1950s, and the significant role played by Sidney Janis.

Notes

[1] Freeman’s/Hindman, 2024. Antiquities and Ancient Art, Freeman’s/Hindman, Chicago, May 23, 2024, lot 265.

[2] Cozzi, Salvatore. 1896. “Regione II (Apulia). XIII. Canosa di Puglia.” Notizie degli Scavi di Antiquità: pp. 491-495, esp. p. 495, no. 12.

[3] Oliver, A. Jr. 1968. The Reconstruction of Two Apulian Tomb Groups, Tomb A: pp. 6-16; Tomb B: 16-21; the head-vase: pp. 4, 5, pl. 10, no. 5. Bern: Francke.

[4] Mayer, Maximilian. 1898. “Regione II (Apulia). X. Canosa.” Notizie degli Scavi di Antiquità: pp. 216-218.

[5] American Art Galleries. 1922. The Remarkable Greek Archaeological Collection from Olbia in South Russia (Chmielowski Collection), American Art Galleries, New York, 22-24 February 1922, lot 185.

[6] Hammer Galleries, New York. Art Objects and Furnishings from the William Randolph Hearst Collection, p. 301, lots 455/3. New York: William Bradford Press.

[7] For more on the Kelekian family’s activities, see Marilyn Jenkins Madina, “Collecting in the ‘Orient’ at the Met: Early Tastemakers in America,” Ars Orientalis XXX (2000), pp 69-89. See also https://www.metmuseum.org/press-releases/coptic-art-2014-exhibitions.

[8] See web label for the Statuette of the Virgin and Child by Julia Perratore, Associate Curator, Department of Medieval Art and The Cloisters.

[9] Archives de Paris; Paris, France; État-Civil 1792-1902. From Paris, France, Births, Marriages, and Deaths, 1555-1929 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2021.

[10] Annalea Tunesi, “Stefano Bardini’s Photographic Archive: A visual historical document” (PhD diss., University of Leeds, School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies, June 2014), p. 106.

[11] Curtis, John E. and Julian E. Reade (eds.), “Assyria Revealed” in Art and Empire: Treasures from Assyria in the British Museum. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995, pp. 210-21; Gere, Charlotte and Judy Rudoe, “The Assyrian Revival” in Jewellery in the Age of Queen Victoria. A Mirror to the World. London: British Museum Press, 2010, pp. 387-97.

[12] McCall, Henrietta, “A Hollywood Mystery: A Pair of Assyrian Revival Urns”, in British Museum, Department of the Middle East Newsletter, 7, 2022, pp. 9-11.

[13] Sidney Janis quoted in Grace Glueck, “Sidney Janis, Trend-Setting Art Dealer, Dies at 93,” The New York Times, November 24, 1989, p. D8.

[14] Emily Genauer, “How Artists Get Into the Majors,” New York Herald Tribune, April 8, 1962, p. C7.