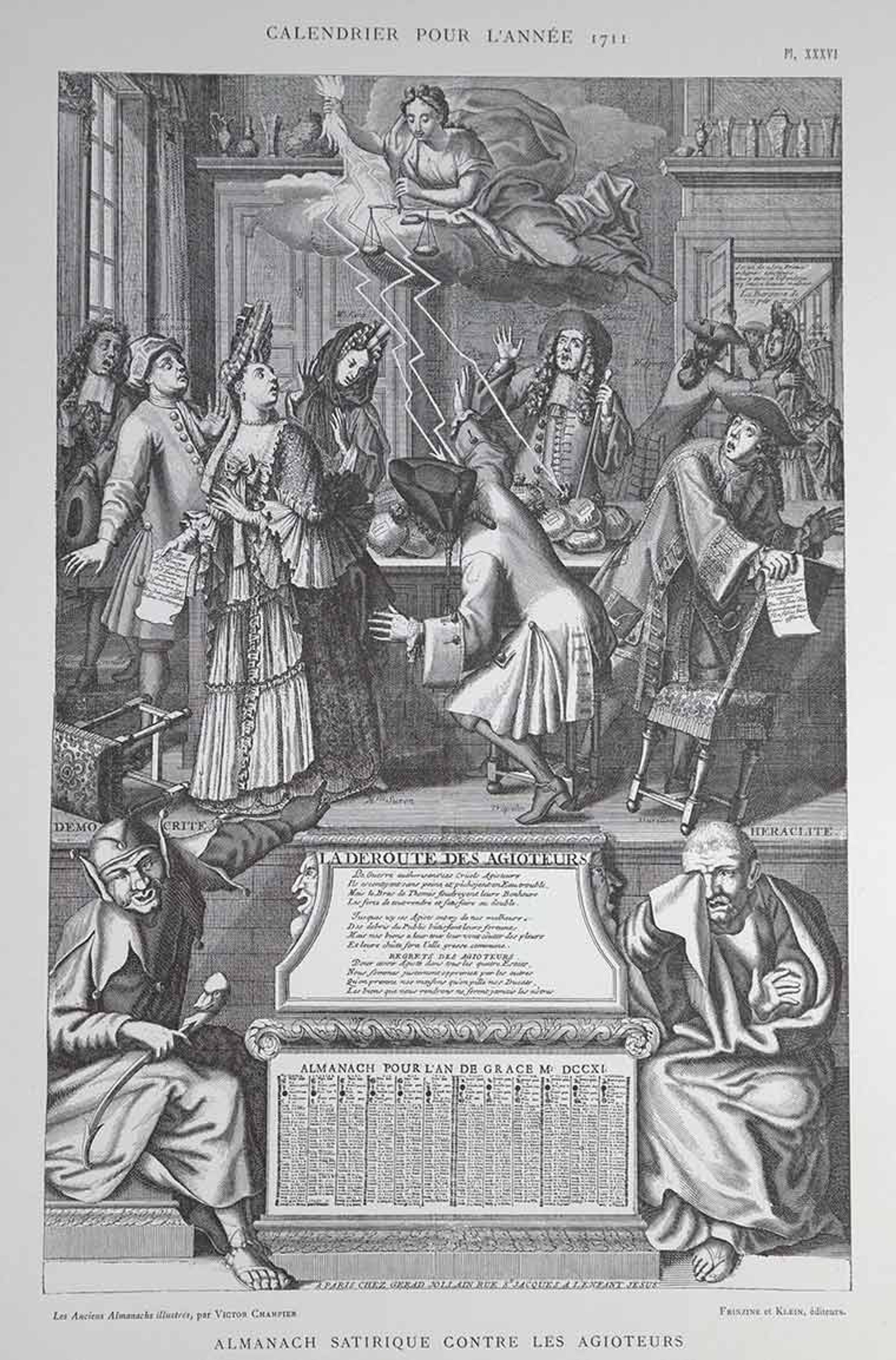

The downfall of dishonest speculators from Les Anciens Almanachs Illustrés: Histoire du Calendrier Depuis les Temps Anciens Jusqu'à Nos Jours (Paris: L. Frinzine et Cie., 1886)

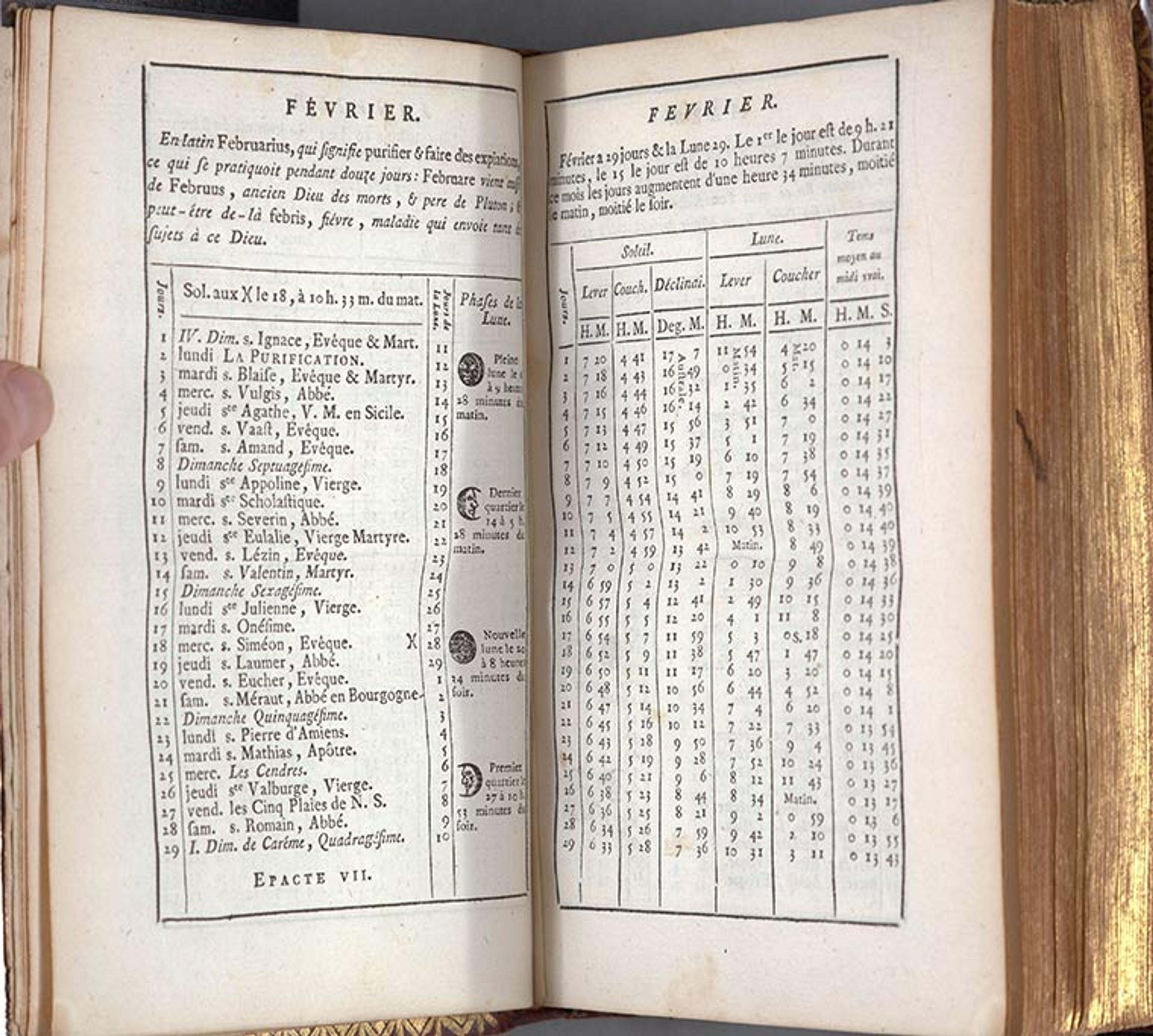

As the year 2019 trundles along, I thought this a suitable time to write about Watson Library's collection of historical almanacs, the majority of which are a gift from Jayne Wrightsman and form part of our fine bindings collection. While some of these almanacs hail from colonial and twentieth-century America, most were published in eighteenth-century France. Following a standard format, they contain a page spread for each month of the year with a list of religious feast days, the rising and setting times of the sun and moon, and instructions for aligning your clock with the sun's movements.

The month of February from Almanach Royal: Année Bissextile M.DCC.LXXXIV ([Paris]: ... Publié et imprimé par D'Houry ..., [1783])

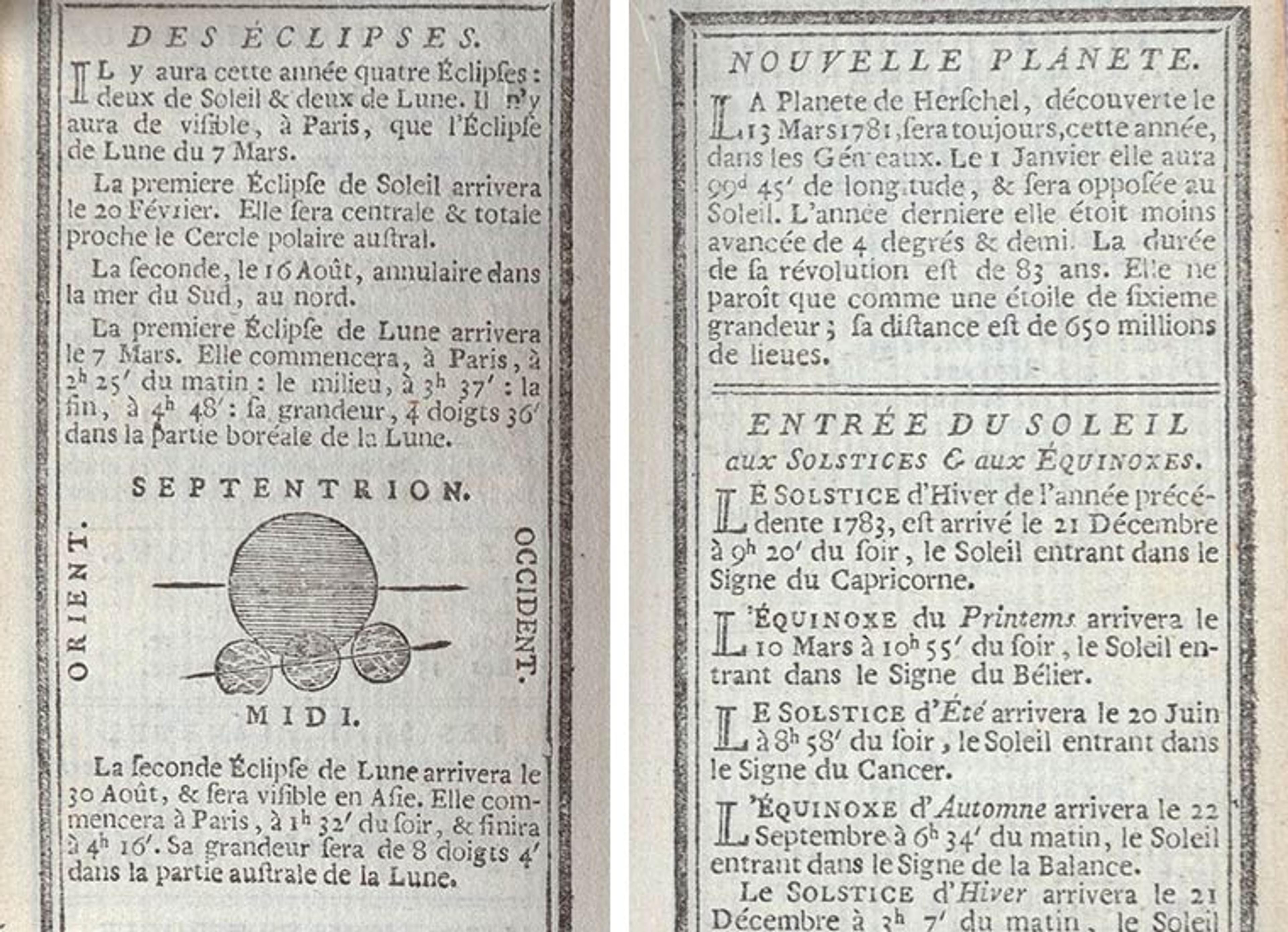

Astronomy lovers will be pleased to find descriptions of various celestial events in these volumes. The images below are from the 1784 issue of Le Calendrier de la Cour. On the verso page, four eclipses—two solar and two lunar—are mentioned, with one of the lunar ones said to be visible from Paris on the seventh of March. The recto page lists the position of the planet Uranus, which was accepted as a planet two years after William Herschel's discovery in 1781.

Left: Upcoming eclipses from Le Calendrier de la Cour: Tiré des Ephémérides, Pour L'Année Bissextile Mil Sept-Cent Quatre-Vingt-Quatre (Paris: Chez la veuve Hérissant, imprimeur du Cabinet du Roi, maison & batimens de sa Majesté., M.DCC.LXXXIV. [1784]). Right: The position of Uranus from the same.

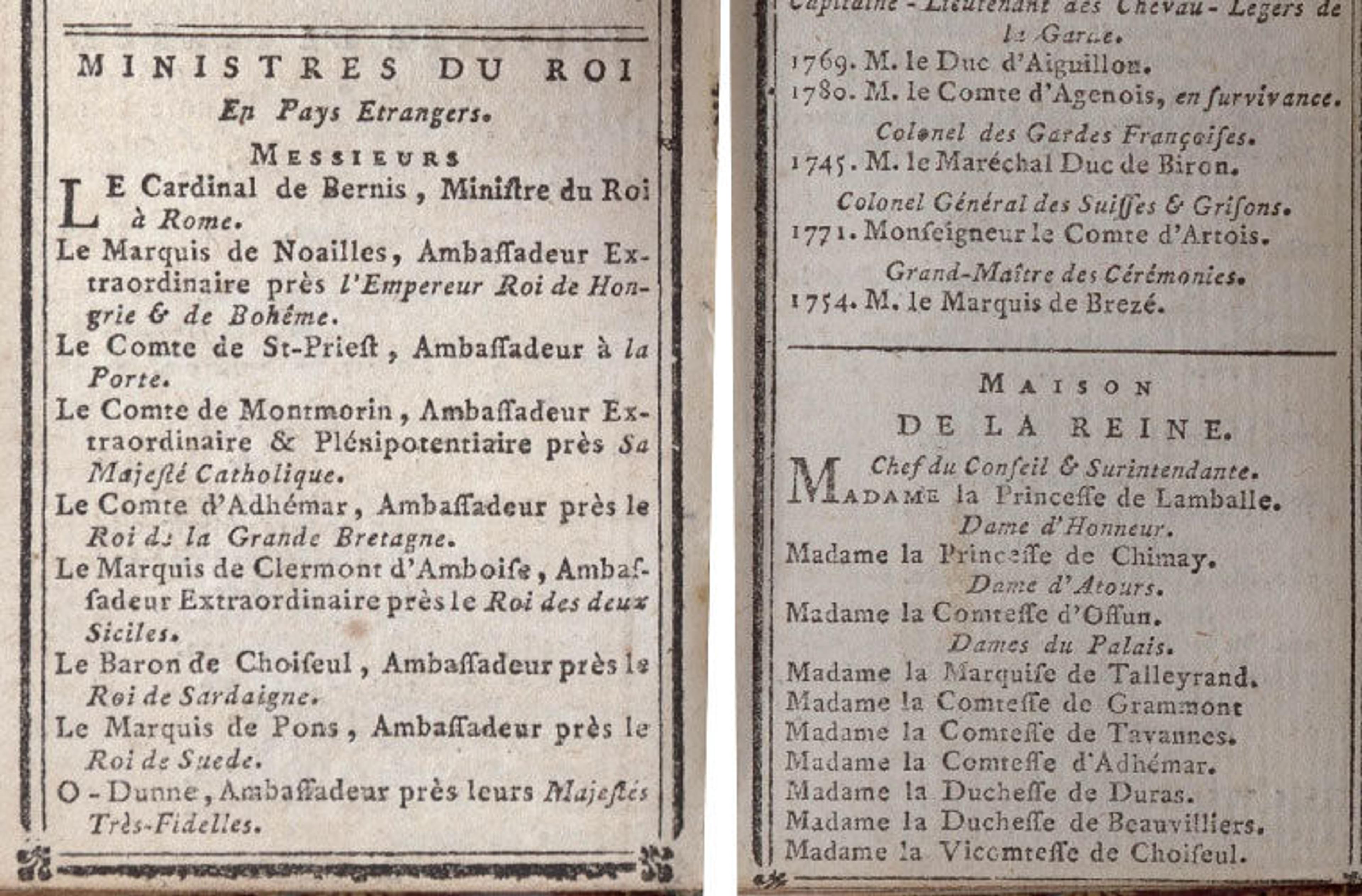

If one wanted to keep their finger on the pulse of royal births, deaths, and marriages in eighteenth-century France, these almanacs would have been essential. In addition to listing royal events, they also include a directory of members of the French government, military, and clergy, and of the various academies, such as L'Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. In the below images from this edition of the Almanach Royal for the year 1784, we can see a list of the king's foreign ministers and members of the Maison de la Reine, Marie-Antoinette's retreat within the Petit Trianon park at Versailles.

Left: The King's foreign ministers from Almanach Royal: Année Bissextile M.DCC.LXXXIV (Paris: Chez D'Houry …, [1783]). Right: Members of the Queen's household from the same.

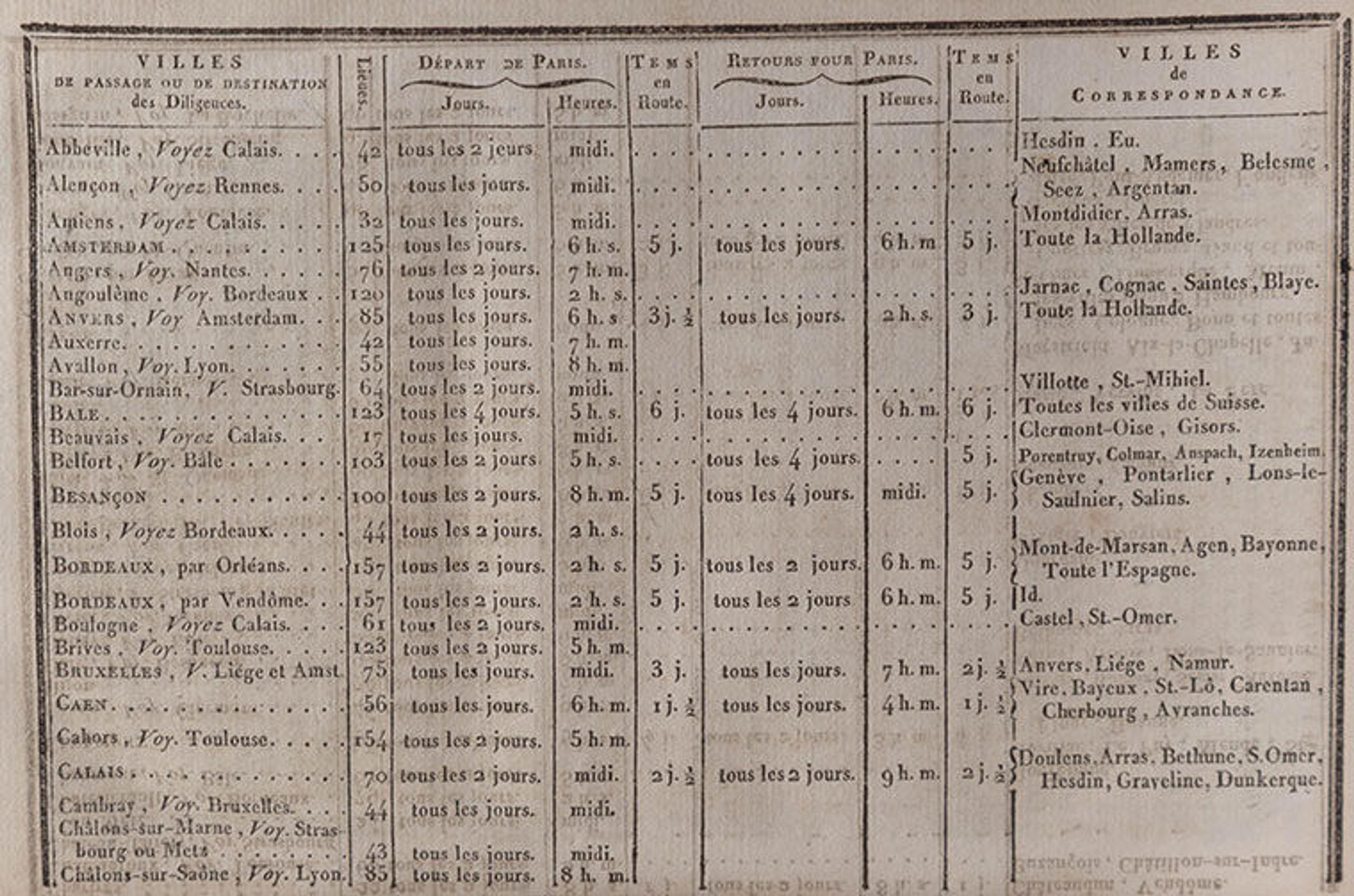

To gain a glimpse of the world in which these almanacs were written, consulting their ship and stagecoach schedules, foreign currency exchange tables, and announcements of fair days can be wonderfully illuminating. According to the 1813 Almanach Impérial, it took a stagecoach five days to get from Paris to Amsterdam.

Stagecoach schedule from Almanach Impérial, Pour L'Année M. DCCC. XIII (Paris: Chez Testu et Ce., [1813])

Some of the most entertaining almanacs in our collection are the ones that include poetic verses, musical scores, and engraved views, as seen in the image below.

The Louvre's colonnade from Petit Almanach de la Cour de France: [1819. Treizième Année] (Paris: Chez Le Fuel, [1818])

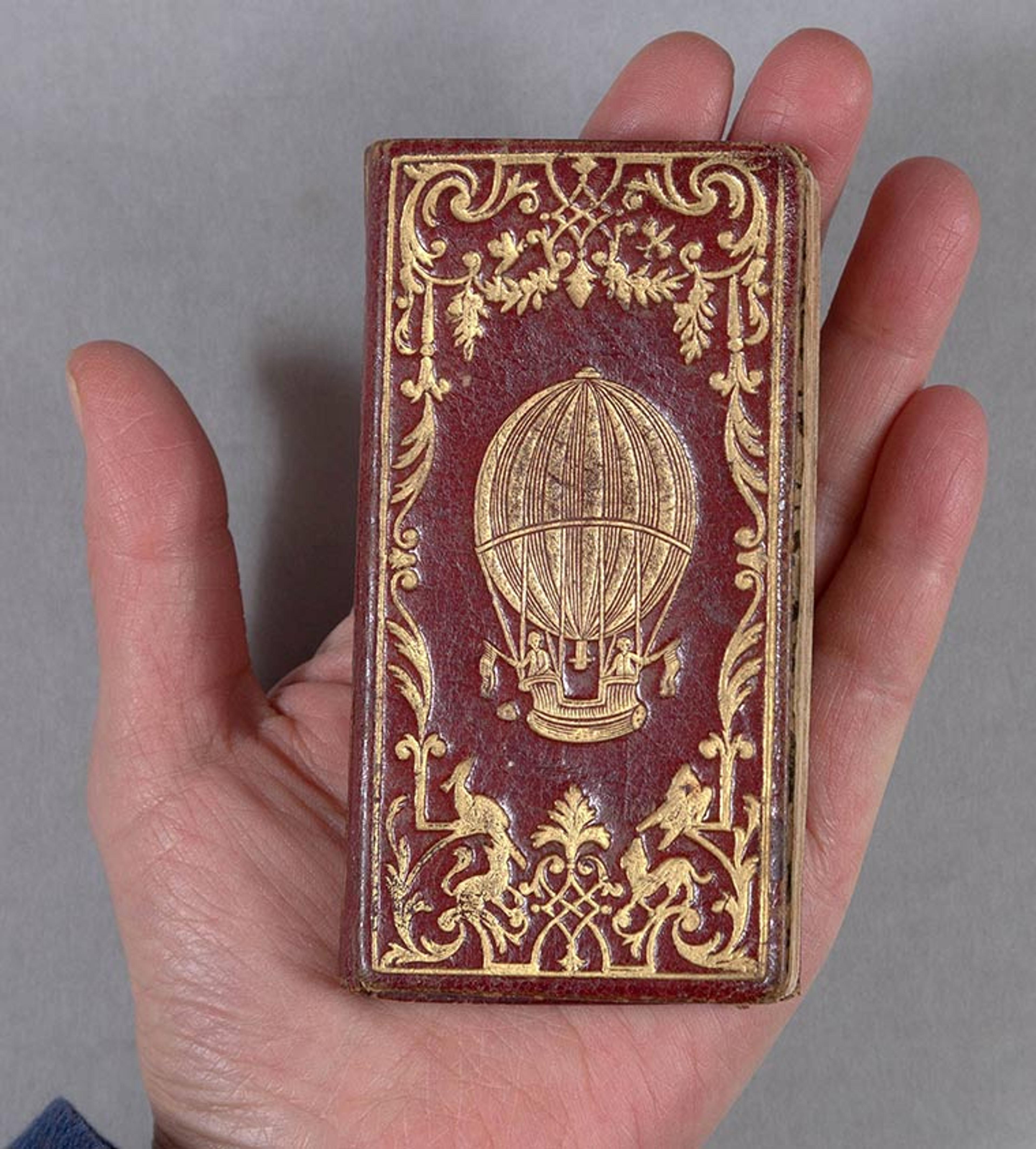

Equally delightful is the diminutive size of many of these almanacs. To wit: Almanach Galant and Le Calendrier de la Cour are a mere 10 and 11 centimeters in height, respectively.

Almanach Galant, Moral et Critique en Vaudevilles Orné de Gravures (Paris: Chez Boulanger, 1779)

Le Calendrier de la Cour: Tiré des Ephémérides, Pour L'Année Bissextile Mil Sept-Cent Quatre-Vingt-Quatre (Paris: Chez la veuve Hérissant, imprimeur du Cabinet du Roi, maison & batimens de sa Majesté., M.DCC.LXXXIV. [1784])

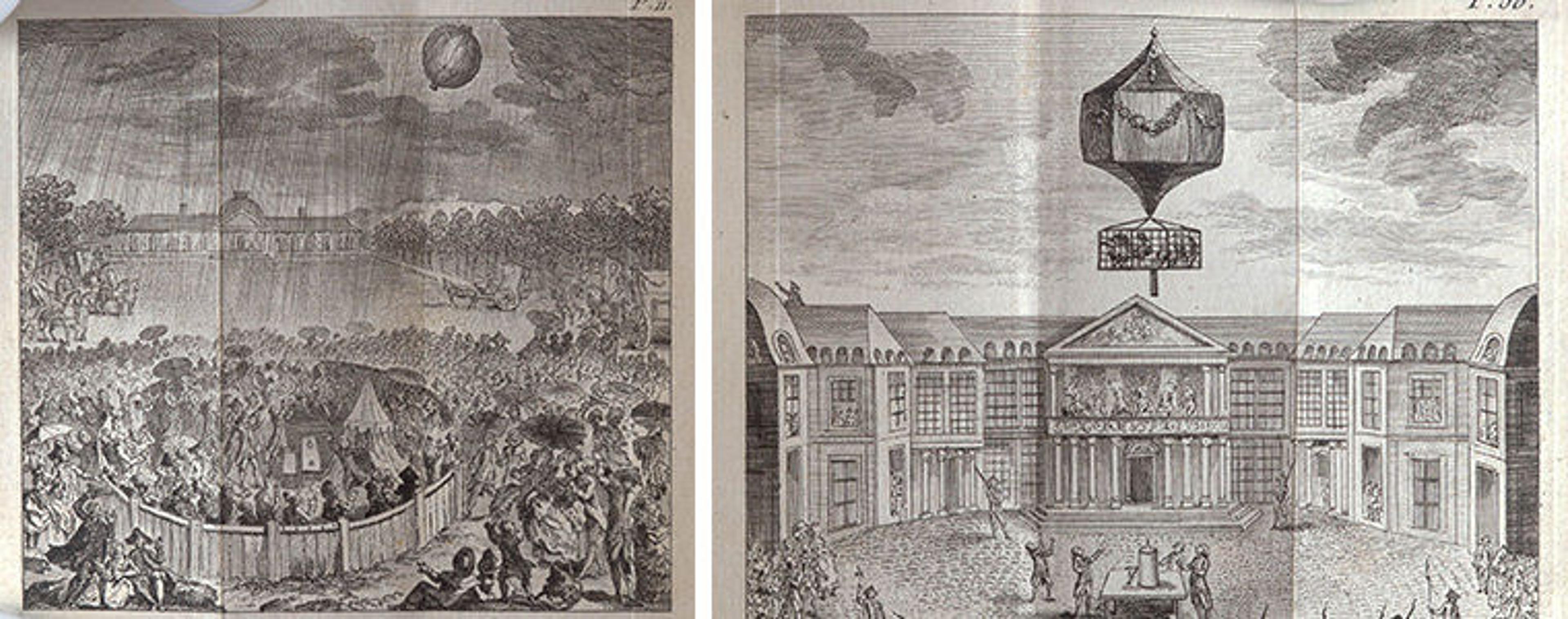

I would be remiss if I did not mention the almanacs that celebrate the sport of ballooning. Representations of this subject can be found in The Met's collection by searching for hot-air balloon and hydrogen balloon. L'Amour Dans le Globe was published by both Desnos and Jubert in 1784, a year after the Montgolfier brothers' first hot-air balloon flight. It contains a collection of poetry, prose, and engravings celebrating this aeronautical event, from the early trials at Champ de Mars to the later demonstrations at Versailles. To get a sense of the tone of this volume, I refer you to one of its poems, Vers Sur le Globe Ascendant, which begins with the line "No, it is not Icarus who dares to leave the earth" and continues with other similarly florid pronouncements.

The balloon demonstrations at Champ de Mars and Versailles on August 27 and September 20, 1783 from L'Amour Dans le Globe; ou, L'Almanach Volant, Composé de Petites Pièces Fugitives, Légères ou Galantes, en Prose & en Vers (Paris: Chez Desnos, [1784])

Not everything always went as planned in the early ballooning world. L'Amour Dans le Globe contains an engrossing rendition of the Versailles balloon demonstration that took place on September 20, 1783 in the presence of the king and royal family (see above-right image). The balloon was said to weigh 1,400 pounds, including the ballast, and to measure 60 feet high and 40 feet wide. Since the objective of this demonstration was to ascertain whether an animal could survive at a considerable height, a basket was attached to the balloon into which was placed a sheep, a duck, and a rooster, along with food supplies. The balloon was expected to rise 12,000 feet and descend after two or three days. Unfortunately, a defect in the canvas' stitching prevented the balloon from rising more than 1,200 feet, causing it to land in the nearby wood of Vaucresson after only eight or ten minutes. The sheep was found eating in its cage, the duck appeared not to have suffered, and there is no mention of the rooster—let us hope he flew the coop.

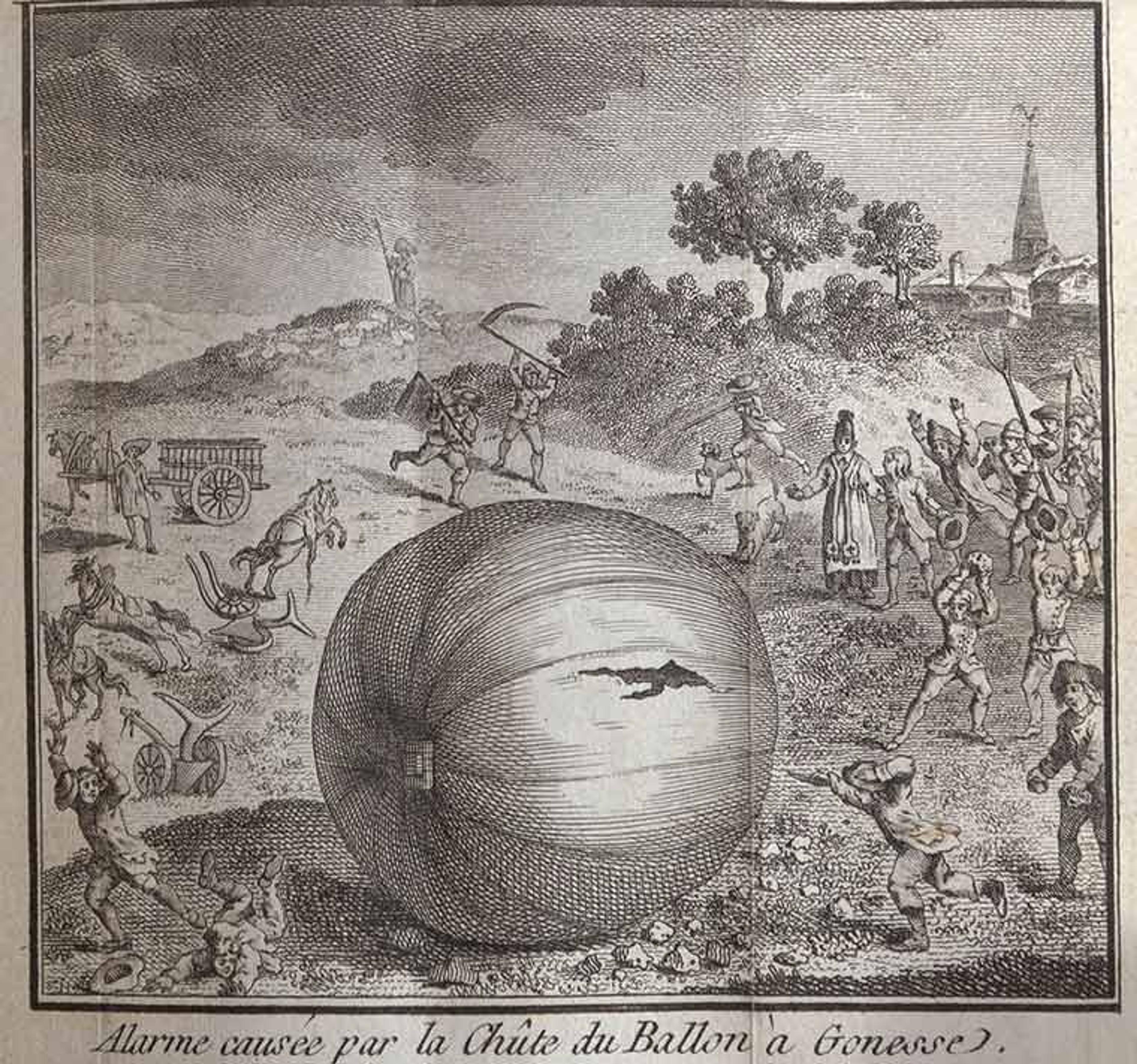

A fallen balloon in Gonesse, near Paris from L'Amour Dans le Globe; ou, L'Almanach Volant, Composé de Petites Pièces Fugitives, Légères ou Galantes, en Prose & en Vers (Paris: Chez Jubert, [1784])

In addition to documenting other ballooning mishaps, such as an incident involving a fallen balloon near Paris (see above image), Jubert's edition of L'Amour Dans le Globe recounts the first hot-air balloon flight with human passengers, which took place on November 21, 1783 at Château de la Muette. The two passengers, Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier and François Laurent, marquis d'Arlandes, are visible in the balloon's basket in the below illustration. In spite of a false start, the balloon rose to a height of 3,000 feet, crossing the Seine, passing between the École Militaire and Hôtel des Invalides, and calmly landing in the countryside outside the boundaries of Paris. The flight took twenty to twenty five minutes.

First hot-air balloon human flight from L'Amour Dans le Globe; ou, L'Almanach Volant, Composé de Petites Pièces Fugitives, Légères ou Galantes, en Prose & en Vers (Paris: Chez Jubert, [1784])

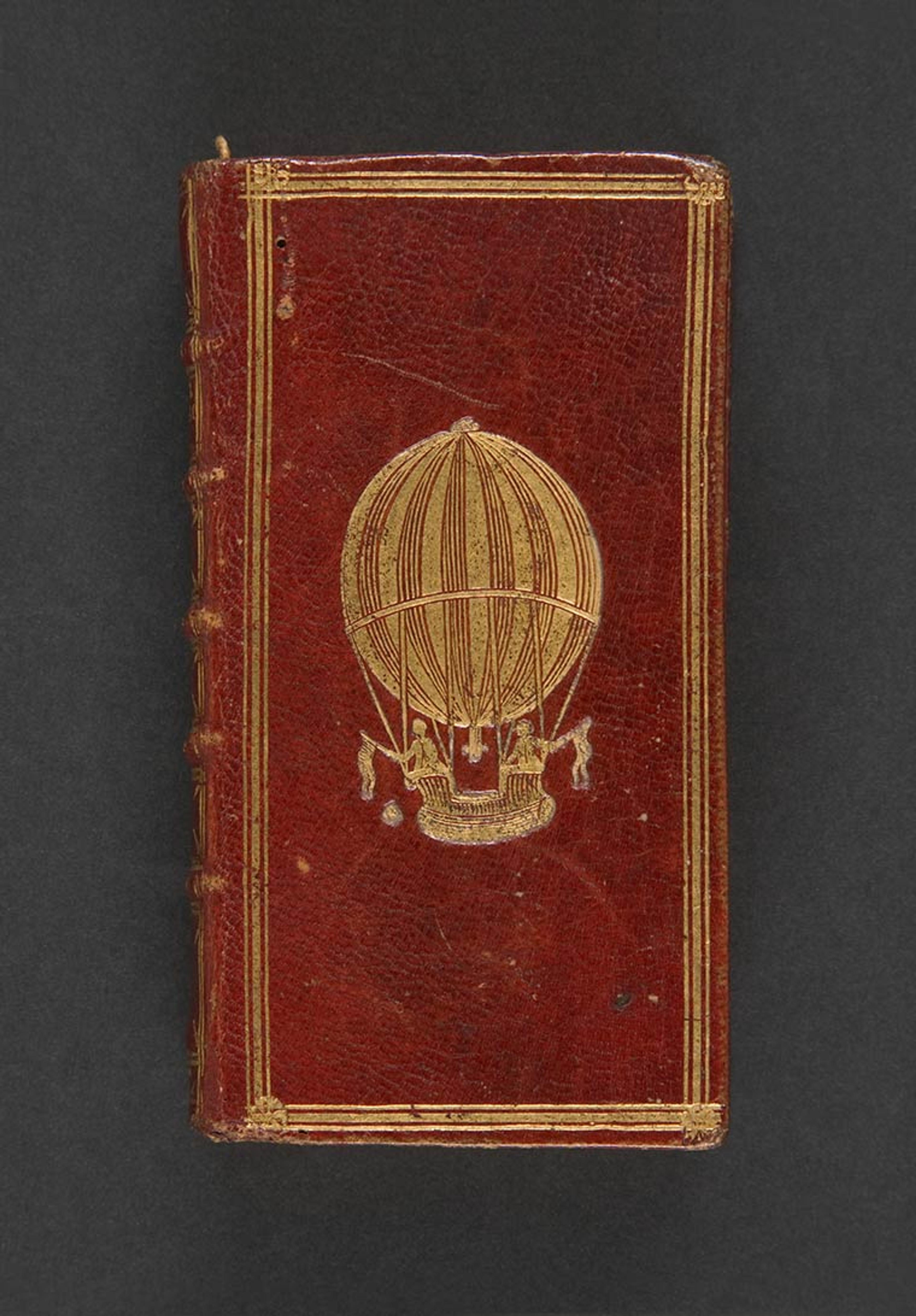

The first hydrogen balloon flight with human passengers—Jacques-Alexandre-César Charles and Marie-Noël Robert, who also developed the balloon—took place on December 1, 1783 and is celebrated in the balloon-shaped finials of these eighteenth-century side chairs from The Met's collection, as well as on the cover of this edition of the Almanach Royal for the year 1784.

Front cover of Almanach Royal, Année Bissextile M.DCC.LXXXIV (Paris: Chez D'Houry …, [1783])

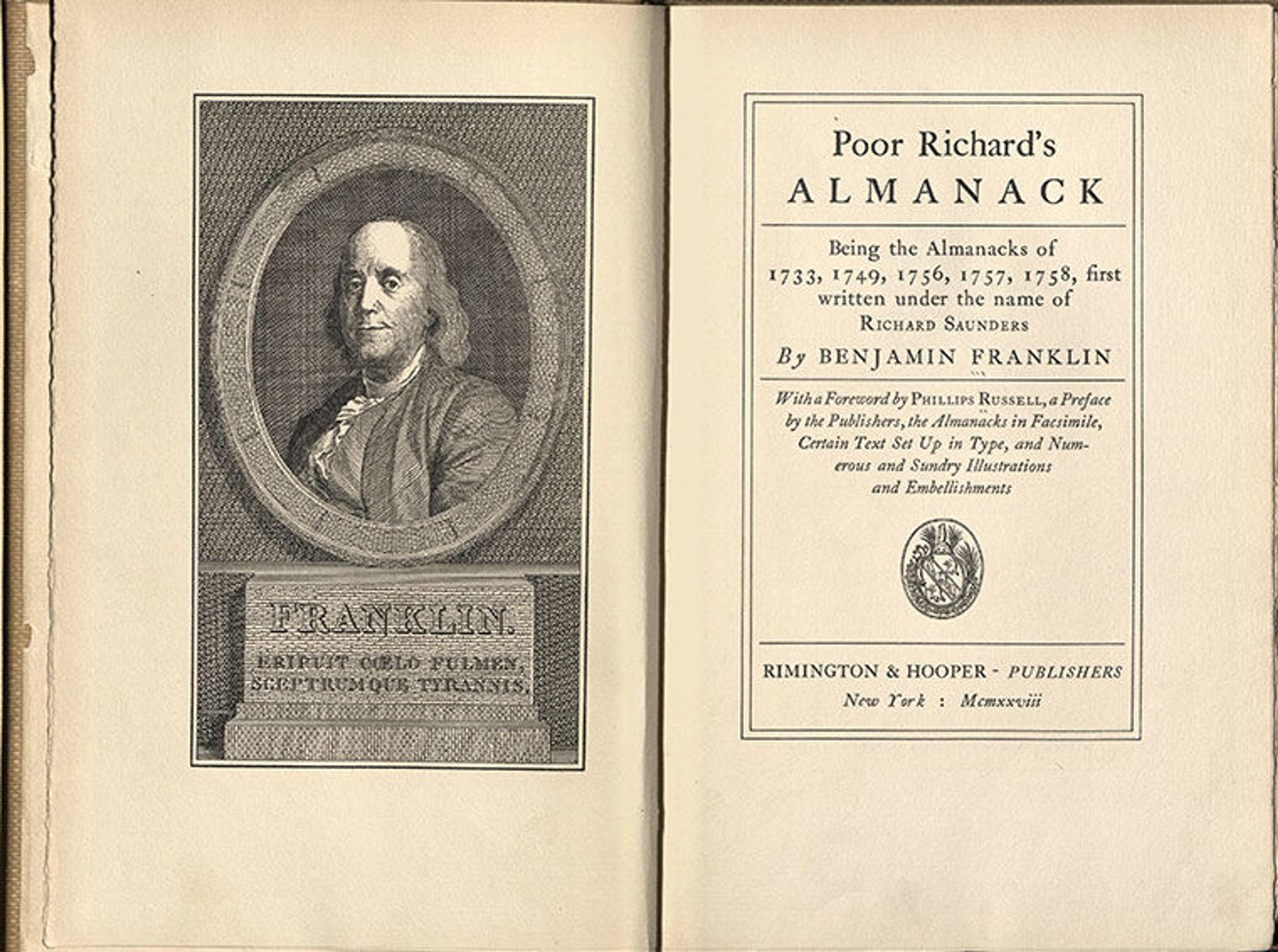

In an interesting trans-Atlantic connection, Benjamin Franklin was one of the spectators who witnessed the first hot-air balloon human flight at Château de la Muette. Using the nom de plume Richard Saunders, Franklin penned one of the most famous American almanac series Poor Richard's Almanack, of which Watson Library owns several facsimile editions. Begun in 1732, this series is peppered with the amusing aphorisms of the character of Poor Richard, including "Half the truth is often a great lie" and "The first mistake in public business, is the going into it."

Title page from Poor Richard's Almanack: Being the Almanacks of 1733, 1749, 1756, 1757, 1758, First Written under the Name of Richard Saunders, by Benjamin Franklin; With a Foreword by Phillips Russell, a Pref. by the Publishers, the Almanacks in Facsimile, Certain Text Set up in Type, and Numerous and Sundry Illus. and Embellishments (New York: Rimington & Hooper, 1928)

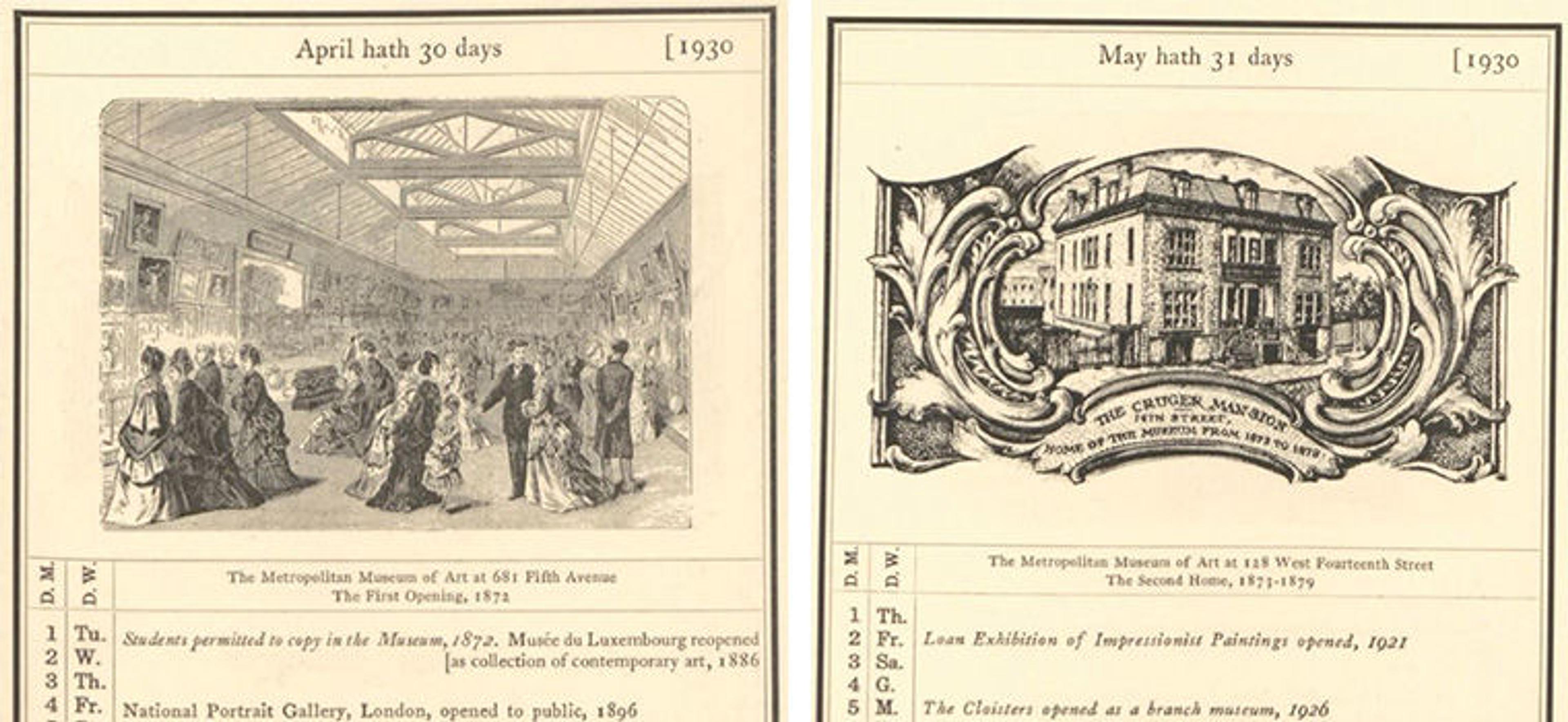

Even The Met published an almanac in 1930 to celebrate its sixtieth year. Each month includes listings of historical events related to the Museum and other art institutions, such as the first exhibition of the Department of Prints in April 1917 and the opening of the British Museum in January 1759.

The months of April and May from An Almanac for the Year 1930: Being the Sixtieth in the History of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Incorporated April 13, 1870 (New York: [Printed at the Museum Press], 1930)

I will end this peregrination through our almanac collection by mentioning two almanac bibliographies that one could consult for further research: Les Almanachs Français (1896) and Les Anciens Almanachs Illustrés (1886). This post's first image, which satirically depicts the defeat of unscrupulous financial speculators, is from the latter title. While my current wall calendar does not contain images nearly as dramatic, understanding its evolutionary history has given me a new appreciation for its design.

Thanks to Yukari Hayashida, Senior Book Conservation Coordinator in the Thomas J. Watson Library, for her assistance in photographing this collection.