When The Met closed its doors in March of this year, it began a new, uncertain chapter in the institution's 150-year history. We invited staff from across the Museum to send us dispatches from wherever they may be, about the innovative ways they were able to adapt, create, and care for the collection and each other as the world was struck by new and dangerous circumstances. This is the second installment of a four-part series.

– The Editorial Team, Digital Department

'Safe and Sound': Jim Moske, Managing Archivist and Collection Monitor

Collection Monitors Ted Hunter, Jim Moske and Jennifer Perry in the Asian Art galleries, March 28, 2020. Photograph by Meredith Reiss

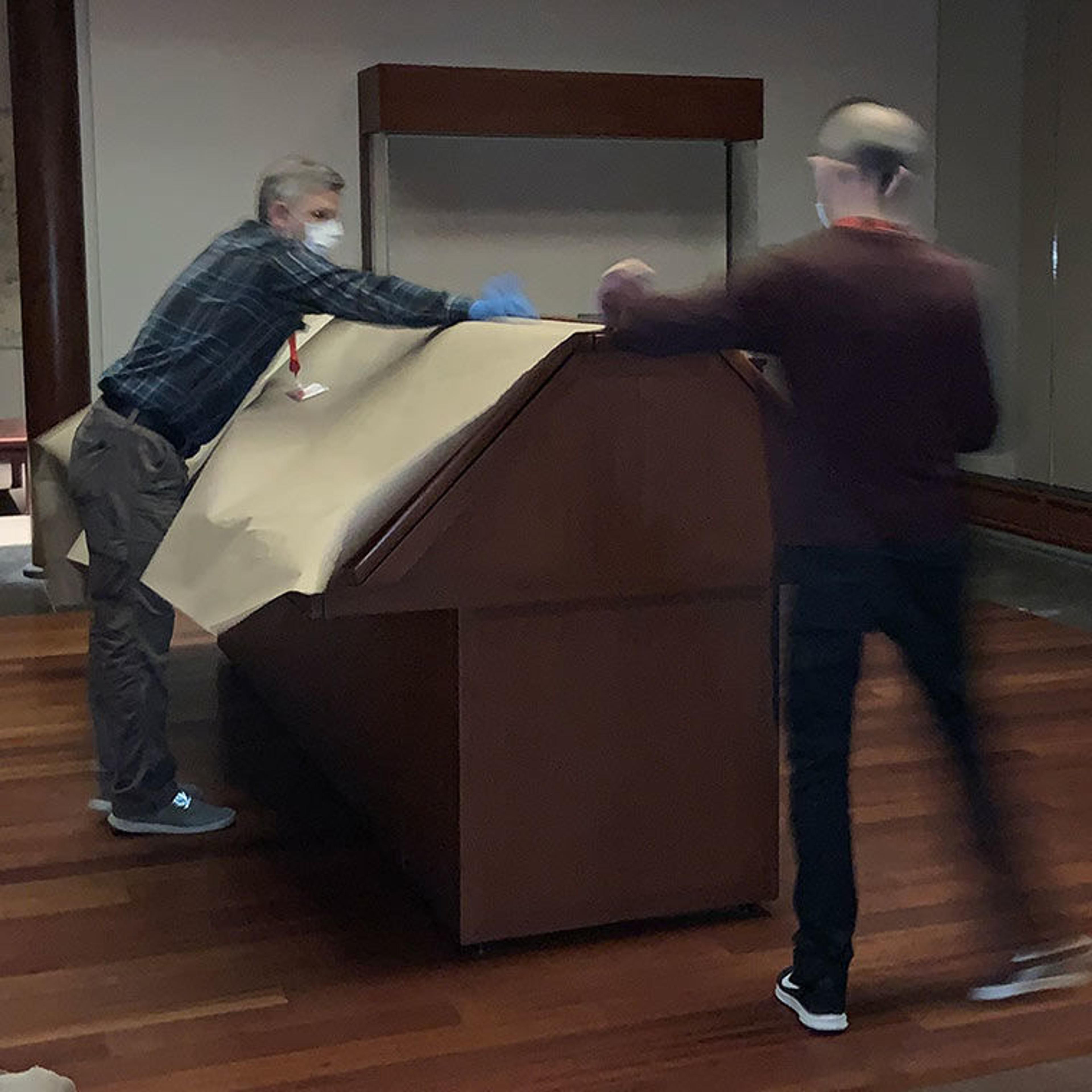

During the Met's extended closure I served on a team of 40 essential staff who monitored the empty Museum and patrolled galleries, art storerooms, conservation labs, libraries, and archives. This safeguarding effort was organized by the Museum's Collections Emergency Working Group—staff members who manage emergency planning and response activities—and was carefully planned in coordination with The Met's security team, keeping the health and safety of all staff as a priority. The patrols—carried out using PPE and physical distancing—allowed us to check conditions in special exhibition galleries, to ensure that light-sensitive artworks in galleries were protected for the duration of the closure, to assess climate control, and to look for leaks or pests in archives, libraries and art storage rooms.

Collection Monitor rounds, Spring 2020, photographs and video still by Pari Stave

To be inside the empty Museum at this historic time felt sad and eerie, though it was also comforting to ensure that the collection was safe and sound. The magical silence that surrounded the artwork was deeper and richer than what I've heard during closed-hours of ordinary days. Colleagues who served alongside me as collection monitors captured many beautiful images of Met galleries and artworks waiting patiently for visitors to return.

'A Big Change': Kamaria Hatcher, Assistant Museum Librarian, Reader Services, Nolen Library

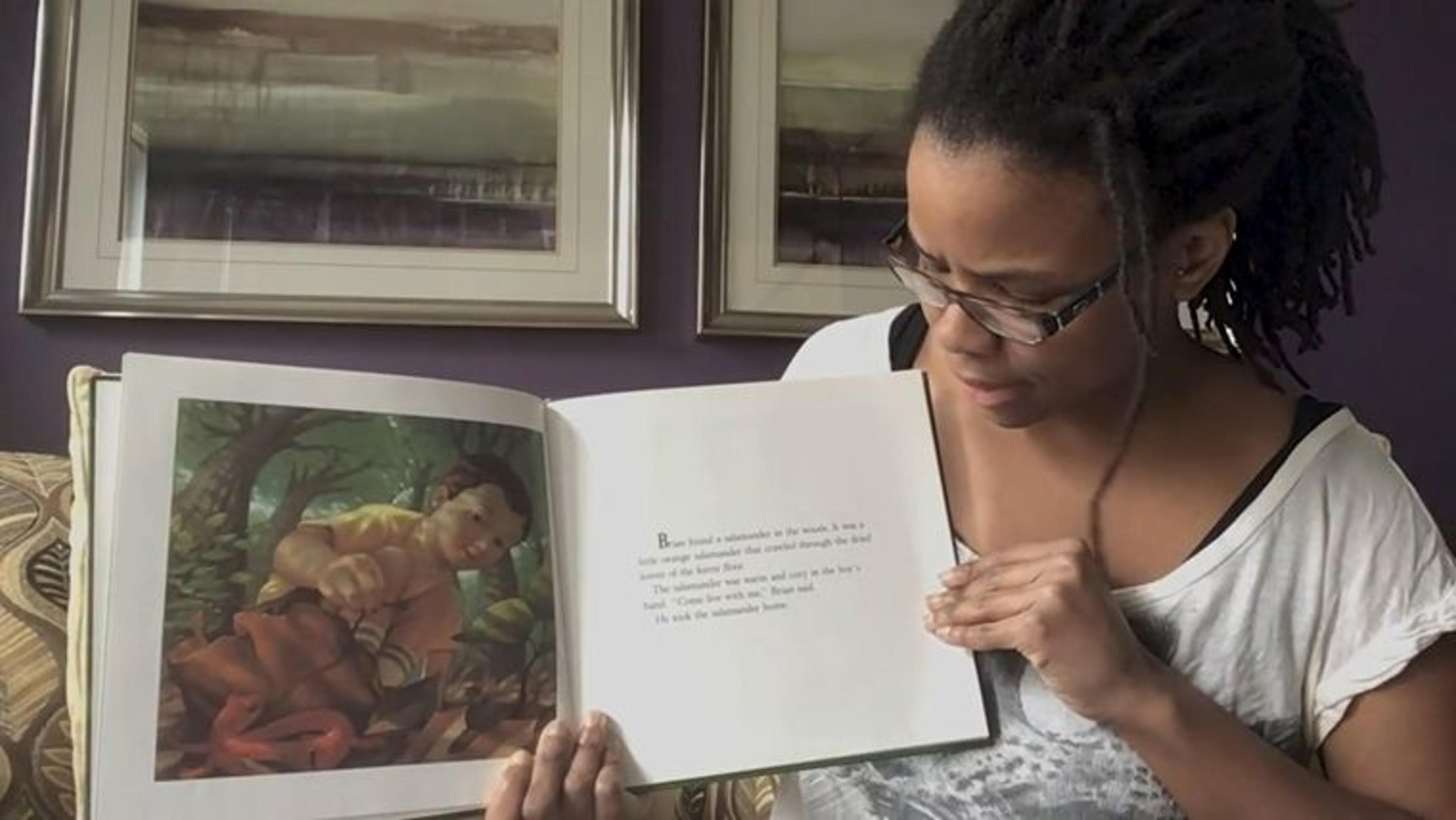

Recorded from home, Kamaria Hatcher reads from The Salamander Room by Anne Mazer in for a virtual Storytime with The Met.

Transitioning Storytime with The Met from in-person, interactive programming at The Met's Nolen Library to a virtual setup has been challenging, not in the least because we miss our great audience of children and their adults. Since the closure began, we've had to learn how to film from home and adapt our practices to the new format.

Employing a small tripod and a lamp, Hatcher converted her living room into a makeshift set. Image courtesy of Kamaria Hatcher

Because the videos are prerecorded, we've had to find new ways to make the audience feel included. I've never been super comfortable appearing on camera, but it's important to show a human face and be able to speak directly to our listeners, asking questions about what they see and the characters in the story, just like we do in person. A big change was to introduce crafts and activities that viewers can do at home, which highlight an object from the Met collection that relates to the book we are reading. It's one of the nicer changes; it's not something we were able to do before and it brings kids closer to the art in a new way.

'What I Miss the Most': Maria Goretti Mieites Alonso, Associate Laboratory Coordinator, Department of Scientific Research

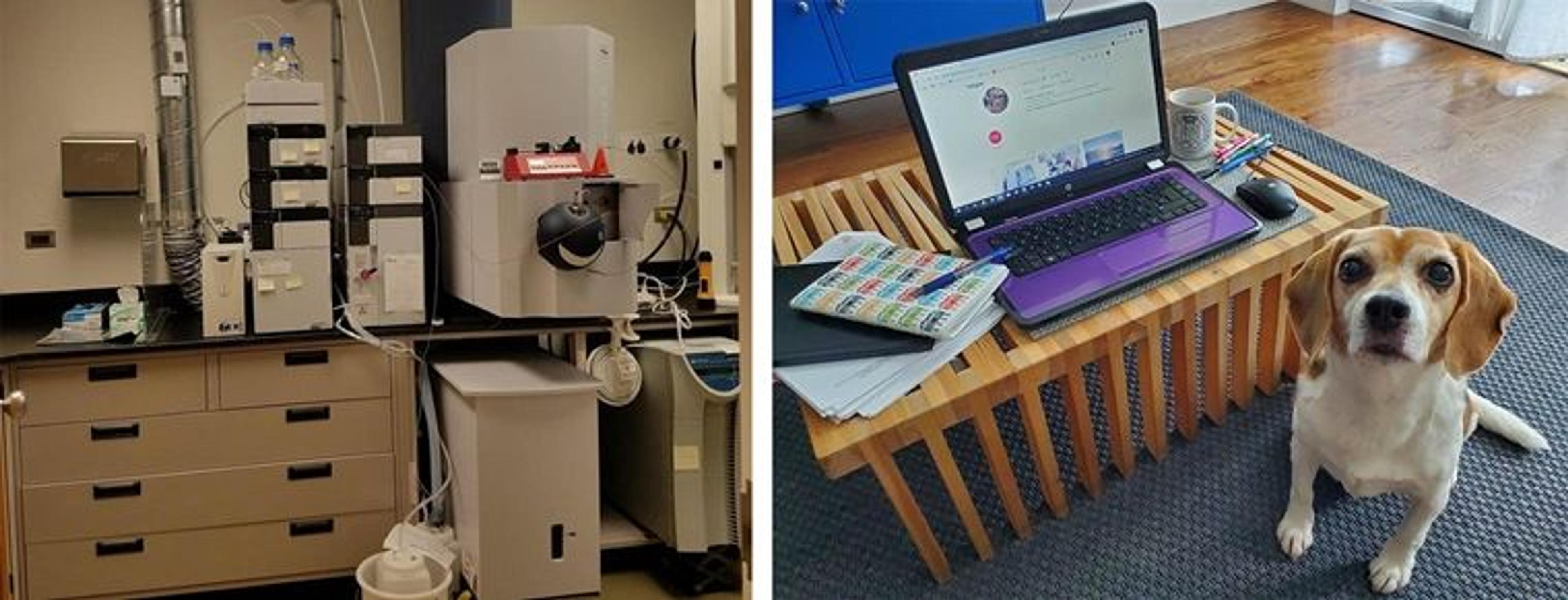

The author at her home office. Image courtesy of Maria Goretti Mieites Alonso

Remotely managing The Met's science laboratories during the lockdown was a challenge. Most of the Scientific Research team were working from home, so coordinating their ability to remotely access databases and control scientific equipment was an undertaking that we have never had to deal with before. At the same time, our preventive conservation scientists were part of the essential personnel that worked at The Met, so it was crucial for me to assure the procurement and delivery of all the materials they needed to implement experiments and care for our collections.

Effective coordination made it possible to ensure that all of the working spaces in our department, as well as the Museum's galleries and art storage, were safe from environmental damage and remained in good condition.

Having limited access to our scientific equipment was a big challenge, as well. Unfortunately, there was no way for me to bring home the six-foot-tall mass spectrometer that I use for the analysis of dyes and pigments. So I focused on other tasks, like analyzing data that I had acquired before the closure and performing bibliographic research for future projects that may be developed once we have full access to our spaces again.

Left: The towering mass spectrometer installed at The Met's Department of Scientific Research. | Right: A scene from Mieites Alonso's home office. Images courtesy of Maria Goretti Mieites Alonso

I have to admit that I've enjoyed spending time with my new (four-legged) coworker. But seeing my colleagues from Scientific Research every day is what I miss most from the pre-pandemic era. Working with people that you feel comfortable with is invaluable, and I'm looking forward to going back to the museum and being able to share lots of new projects, laughs, and—of course—even complaints about our daily commutes!

'A Moment to Connect': Bryan Martin, Production Coordinator, Digital Department

The Met's Great Hall, pictured during closure, was inaccessible, to visitors hoping to experience art for more than five months. Image courtesy of Bryan Martin

One of the most comforting things to me about art is experiencing something stimulating and beautiful every day through my job at The Met, or while visiting other museums and galleries. To me, it is a welcome routine. Because of our COVID-19-related closure, many of the in-person routines the Museum normally offers—such as our lectures, tours, performances, and classes—were put on hold. But in a colossal effort, we were able to translate these programs into a series of ongoing virtual events that provide new opportunities to learn about art.

What you don't see when you participate in these virtual programs is the nervous Met staff recording from their computers—camera off and microphone on mute—hoping their WiFi doesn't go out and ruin the presentation. In one instance, the internet connection in my apartment actually dropped over ten times during a conversation between the artist Wangechi Mutu and Met curator Kelly Baum, causing the audio to go in and out throughout the recording. I panicked. We had spent weeks carefully organizing this hour-long conversation between Baum, at home in Westchester County, NY, and Mutu in her Nairobi, Kenya, studio.

Met curator Kelly Baum (left) and artist Wangechi Mutu (right) broadcast a trans-global conversation as part of a virtual event.

Luckily, we planned ahead and had multiple staff on the call who captured perfect audio recordings as back-up. In the end, we were able to produce a conversation that offered a profound meditation on the role of art institutions in promoting equity and justice. This event, like all our other virtual events, provided its audience with a moment to connect with art during a time when it seems impossible, but necessary, to do so.