When The Met closed its doors in March of this year, it began a new, uncertain chapter in the institution's 150-year history. We invited staff from across the Museum to send us dispatches from wherever they may be, about the innovative ways they were able to adapt, create, and care for the collection and each other as the world was struck by new and dangerous circumstances. This is the third installment of a four-part series.

—The Editorial Team

'Pests didn't get the memo': Michael Millican, Integrated Pest Management Administrator

With many of the building's lights turned off to save power, Millican stands at the top of The Met's main stairwell.

The pests of NYC didn’t get the memo about the pandemic. The Met's Integrated Pest Management (IPM) program needed to continue as usual while adapting to these sudden, unusual circumstances. The pests we encounter—common museum pests include rodents, roaches, and both fabric, and wood-destroying insects—thrive on human activity: our food, water, shelter and sometimes, in the case of a museum, art. The absence of visitors deprived pests of their regular food sources, but it also made pest activity difficult to assess.

The Met Staff are the eyes and ears of the museum. Each department has members dedicated to monitoring for pest activity in the Museum and the Collection. With most of the staff working from home, we developed a plan to monitor the 21 wings and 2.2 million square feet of the museum offices and galleries on a regular basis. (Taking into account utility lines/rooms, attic spaces, drop ceilings and other parts of the museum that can be used as walkways for pests, the square footage I deal with is probably many times greater.) I was lucky to have the cooperation of The Collections Emergency Team (CET), a group of 40 staff members who are specifically trained to collaboratively respond to collections emergencies across the Museum, our essential staff in the Buildings and Security Departments and our pest management vendors. I split the museum into thirds (South, Center, and North) and tried to inspect the entire museum every week. In combination with regular building inspections by The CET and essential staff we were able to maintain a robust pest monitoring, reporting, and response system from March through August, when the Museum reopened to the public.

I spent this time exploring how the building fits together and identifying building improvements related to pest prevention. Urban pest behavior changes with human behavior. The drastic changes in human activity during the pandemic have altered pest behavior in New York City. Those changes give us insight into how we can control and prevent their activity near or in the museum. The opportunity to observe the museum dormant allowed me to identify changes to the building that are essential to the mission of the IPM Program to ensure the safety and care of the Museum’s collections and keep the museum pest-free.

Even without our visitors, the museum still feels like a living, breathing behemoth. At times I’ve felt caught in an eddy of history walking in the empty galleries while 2020 continues outside. This has been a stressful yet productive 6 months. I am very excited to see familiar faces as we get back to the essential work of The Met.

'Each day required constant reevaluation': Victoria Martinez, Social Media Producer

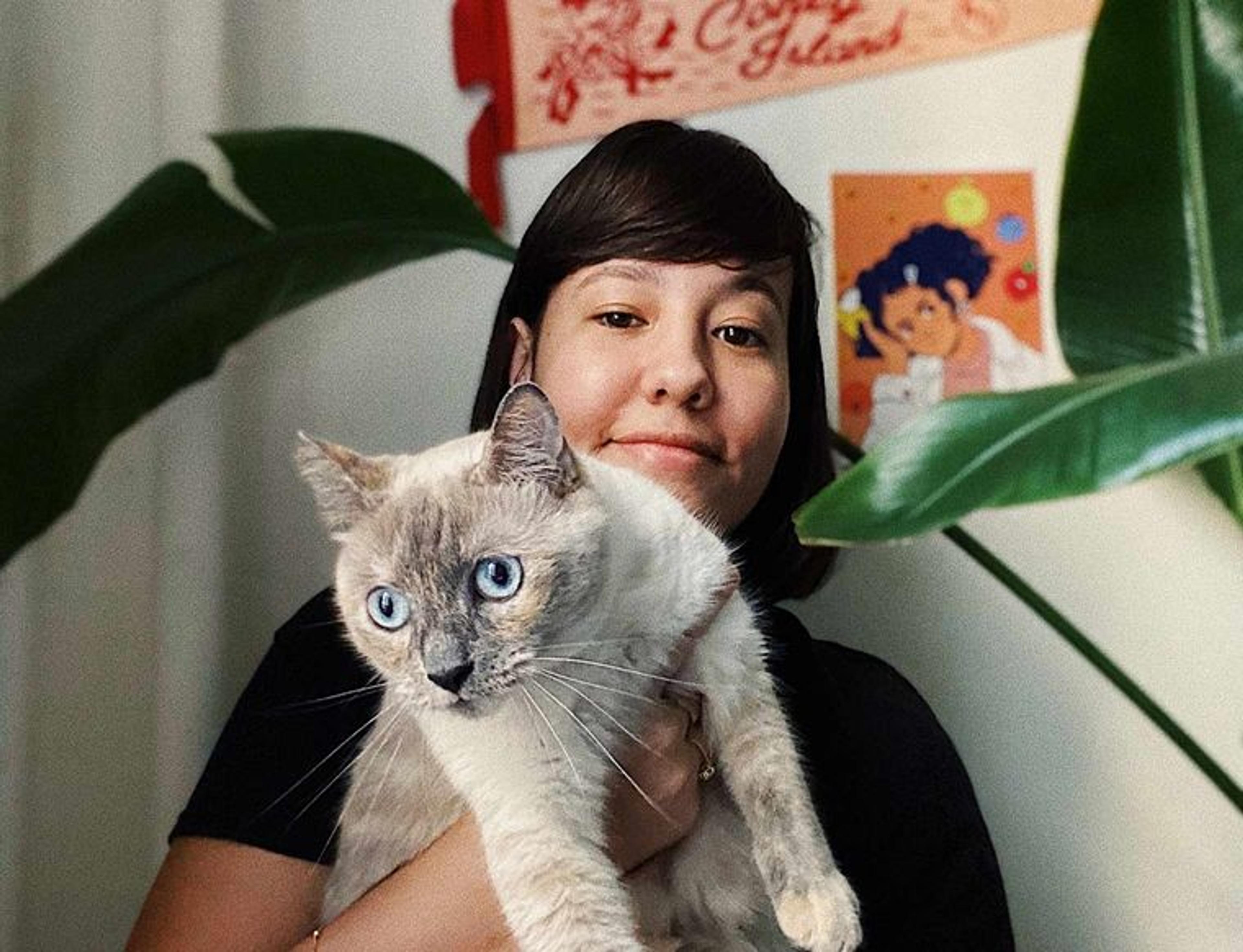

Martinez at home, where she operates The Met's many social media accounts. Image courtesy of Victoria Martinez

I've always had a hard time staying off my phone, as it is incompatible with my role as social media producer at The Met. Starting when the Museum closed in mid-March, my workload doubled and the content I produce each day required constant reevaluation. My team endeavored to serve our audiences in critical new ways during a period that saw a global pandemic; an ongoing call for racial justice and equality reignited by the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and countless others; an explosion in Beirut, Lebanon; raging wildfires in California; and unfortunately, many other global tragedies.

It is not an understatement to say that I, alongside our Museum's collective 10 million followers have experienced nearly every human emotion during these past few months. My challenge was to acknowledge these feelings and sincerely connect with our audience in engaging ways. This ranged from lighthearted content, like the incredibly popular #MetTwinning series (which invited gallery-worthy recreations of works in the Met collection by our followers), to more reflective moments, like our series that honored the thirtieth anniversary of the Americans with Disability Act by inviting reflections from Disabled artists on objects in the Met collection.

Various images posted on The Met's social media accounts during Museum closure

The Met's buildings may have been closed, but our digital doors never shut. As members of The Met's social media team, we've reimagined our roles as stewards of the connection between the Museum and its virtual visitors, with huge help from both our colleagues and the communities we serve every day.

'Burnout is an issue': Christopher Singh, Emergency Preparedness Security Manager

Burnout is an issue that each essential worker has had to face. You have to take on additional duties that colleagues in other departments would usually do. The moment I heard The Met Fifth Avenue was entering lockdown due to the pandemic, I knew we had a lot to do in order to prepare for the uncertain duration of closure.

The threat of a fire poses the greatest danger to museums; I mitigated the risk by having the gas to the stoves in our restaurant, cafés, and employee dining areas turned off and having non-essential appliances like microwaves and toaster ovens in office spaces unplugged. Pandemic-related safety protocols required me to take on an additional duty: receiving and moving the personal protective equipment, or PPE, shipments for Museum staff. I began my career at The Met in the Retail Department and leveraged my experience setting up stock rooms and sales floors to organize and track the inventory.

The protesting that occurred throughout the city heightened the stress during my team’s perimeter patrols. During one such patrol, I discovered a woman who was kicking the bottom of one of the Petrie Court doors. I instructed her to stop and asked if she needed any assistance, she replied, "the museum has been abandoned." I responded, "No, I am from Security and we are always here." The woman walked off and the doors did not sustain any damage.

I found that compartmentalizing my emotions was the best way to keep focused and ensure that I was providing sound leadership to my staff members. I consider myself fortunate to have family and friends living nearby who provided me with a support system. "How are you and your family doing?" became the normal way to greet each other in the halls each day. Taking time to enjoy my favorite artwork kept things in perspective about why I come in every day.

'We found ourselves scrambling': Benjamin Korman, Producer and Editor, Digital Content

The #MetKids production team directs remotely as #MetKid Lucas crafts projects based on objects in the Met collection. Image courtesy of Benjamin Korman

High above the Islamic Art gallery, on the floor that The Met's digital content and education teams share, is a special table made for filming videos of people's hands. The #MetKids team uses this table to make our series of #Create videos, where young artists aged 7–12 demonstrate art projects based on objects around the Museum. We were all set to film a season of new videos… and then COVID-19 struck.

Instead, we found ourselves scrambling—how could we continue to film without access to our equipment and each other? We decided to order two new sets of equipment—including a light kit, a DSLR camera, a monitor, and a specially-designed tripod like the one we have at the Museum. We sent one to our A/V technician, Lamar Stephens, in Brooklyn, and another to Julie Marie Seibert, a museum educator and mom of a 7-to-12-year-old, in New Jersey. Via video chat, Lamar demonstrated the set-up process from his living room, showing Julie Marie how to build her own at-home studio. Julie Marie's son, Lucas, bravely volunteered to complete all of the activities himself while production associate Emma Masdeu-Perez and I directed from miles apart.

Left: A version of the filming rig, set up in Stephens' Brooklyn apartment | Right: The ad hoc production studio, including art supplies, assembled in a corner of Seibert's New Jersey home. Images courtesy of Lamar Stephens and Julie Marie Seibert

We experienced a handful of unexpected difficulties: connectivity issues, monitors that shut off without warning, and a few much-needed juice breaks. But after three sessions of filming, the project was a success. The result? How to make a banjo, a lantern, a drip-painting, a woven basket, and more… all from the safety of your—and our—own homes.