Two years ago, my sister gifted me a pair of earrings. I would later see a nearly identical pair in The Met’s collection of ancient American art: curved half moons with tendrils spread like sun rays and thinly woven metal braids. While my earrings had been crafted by an artisan in Bogotá, the pair at The Met was made thousands of years ago by the Zenú people in the Caribbean lowlands of Colombia. This was the first time I’d seen Colombian art in a museum outside of the country. It was also the day I realized the extent to which contemporary Colombian art and design is inspired by the country’s diversity and past.

Ear Ornaments. Zenú, Caribbean Lowlands (Colombia). Gold, 1 1/2 × 2 3/16 in. (3.8 × 5.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift and Bequest of Alice K. Bache, 1974, 1977 (1974.271.59)

After international outlets reported on civil unrest and police brutality in early 2021, I searched The Met’s collection to see what other stories of Colombia the Museum’s art could tell. A quick survey of these objects recall myths of golden treasures, mythological underworlds, and memories of childhood and everyday life. From landscapes to urban scenes, tapestries to golden artifacts, each object reveals a fragment of Colombia’s spirit.

* * *

The first time I saw a painting by a Colombian artist was at a restaurant in Miami. Above the cases of corn cakes, empanadas, and postre de natas hung two framed posters: One depicted a nude woman facing a mirror, her back as wide as the bathroom stall. The second poster reinterpreted the Mona Lisa, her swollen face pleating gently into her neck. The figures looked so heavy they seemed to weigh down on the canvas, yet so inflated they might levitate into the sky. I didn’t know the artist at the time, although he’s one of the most famous Colombian artists in the world. Fernando Botero is known for his gordos, or fat figures, and the style Boterismo is synonymous with humor and political commentary. The artist—who grew up in Medellín, trained as a bullfighter, and painted Pablo Escobar along with the drug-related violence of the 1990s—says that he paints the “sensuality of form.”

Fernando Botero (Colombian, born 1932). Dancing in Colombia, 1980. Oil on canvas 74 × 91 in. (188 × 231.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Anonymous Gift, 1983 (1983.251) © Fernando Botero

Botero’sDancing in Colombia (1980) at The Met depicts a couple in a lively cafe. While the musicians’ fedoras evoke Argentinian tango, the scene maps the basic components of various Colombian gatherings: paired couples, a group of male musicians. It reminds me of the men with accordions who serenade my family with vallenato folk music on New Year’s Eve. It also evokes memories of my father clearing the living room to teach my sister and me how to dance. He would guide us through the undulations of cumbia, merengue, and bachata. Along with reggaeton, this music would follow me throughout high school, family gatherings, and Colombian nightlife.

Botero doesn’t depict a specific event, but rather a ritual. In Colombia, each region has a traditional culture and dialect—there are the costeños, many of whom are Afro-Colombian and Caribbean, from the coast; the rolos from Bogotá, the capital; the list goes on. In many cities, the rich and the poor shoulder one other in an enduring yet fraught coexistence. And yet Latin music seems to permeate these distant regions and levels of society, as well as various salsa festivals that commemorate regional cultural heritage each year. It is a continuum, thriving in childhood and adulthood, the familial and the social, pervading the normally incongruous realms of the formal and informal. When the national soccer team scores a goal, the players will sometimes huddle together on the field and move their feet to a non-existent salsa choke beat. This is how they celebrate: synchronized and united, dancing.

* * *

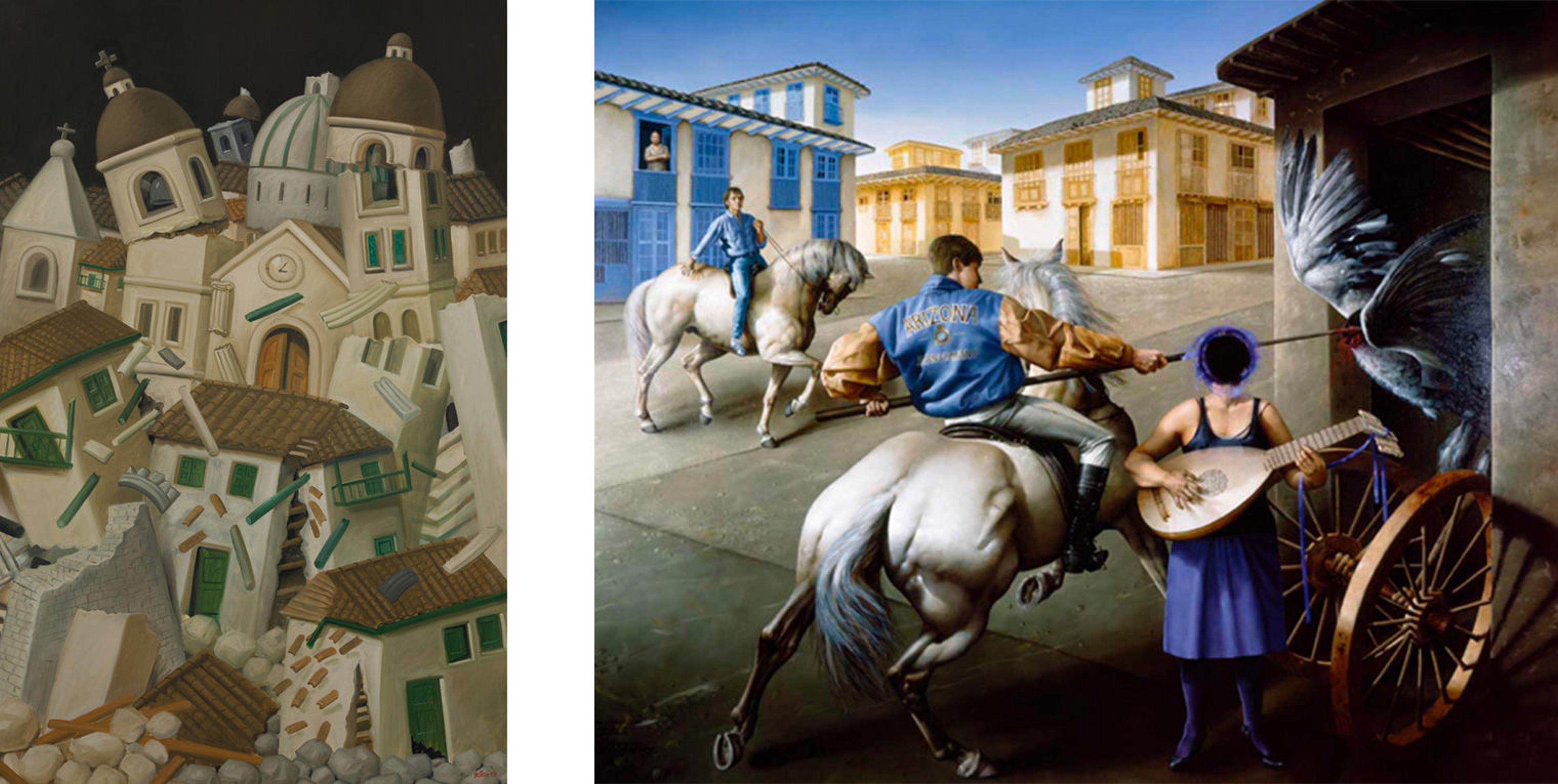

Colombia is predominantly Catholic, and in the nineteenth century small towns or pueblos flourished around a church and plaza that served as the epicenter of daily life. Botero grew up seeing churches, Baroque paintings, and polychrome sculptures. You can see these colonial vestiges in his paintings: bell towers, terracotta tile roofs, white stucco walls, and carved wooden doors. These are also prominent in the works of David Manzur, a painter known for his depictions of horses alongside Baroque and Renaissance motifs. Laced with anachronism, his work brings archetypal figures into the contemporary world.

Left: Fernando Botero (Colombian, born 1932). Terremoto en Popayán, 1999. Courtesy Banco de la República, 2000, Photograph by Víctor Robledo © Museo Botero - Banco de la República. Right: David Manzur (Colombian, born 1929). Doña Cecilia, 1997. Oil on canvas, 63 x 78 7/10 in (160 x 220 cm). Courtesy Galeria Duque Arango

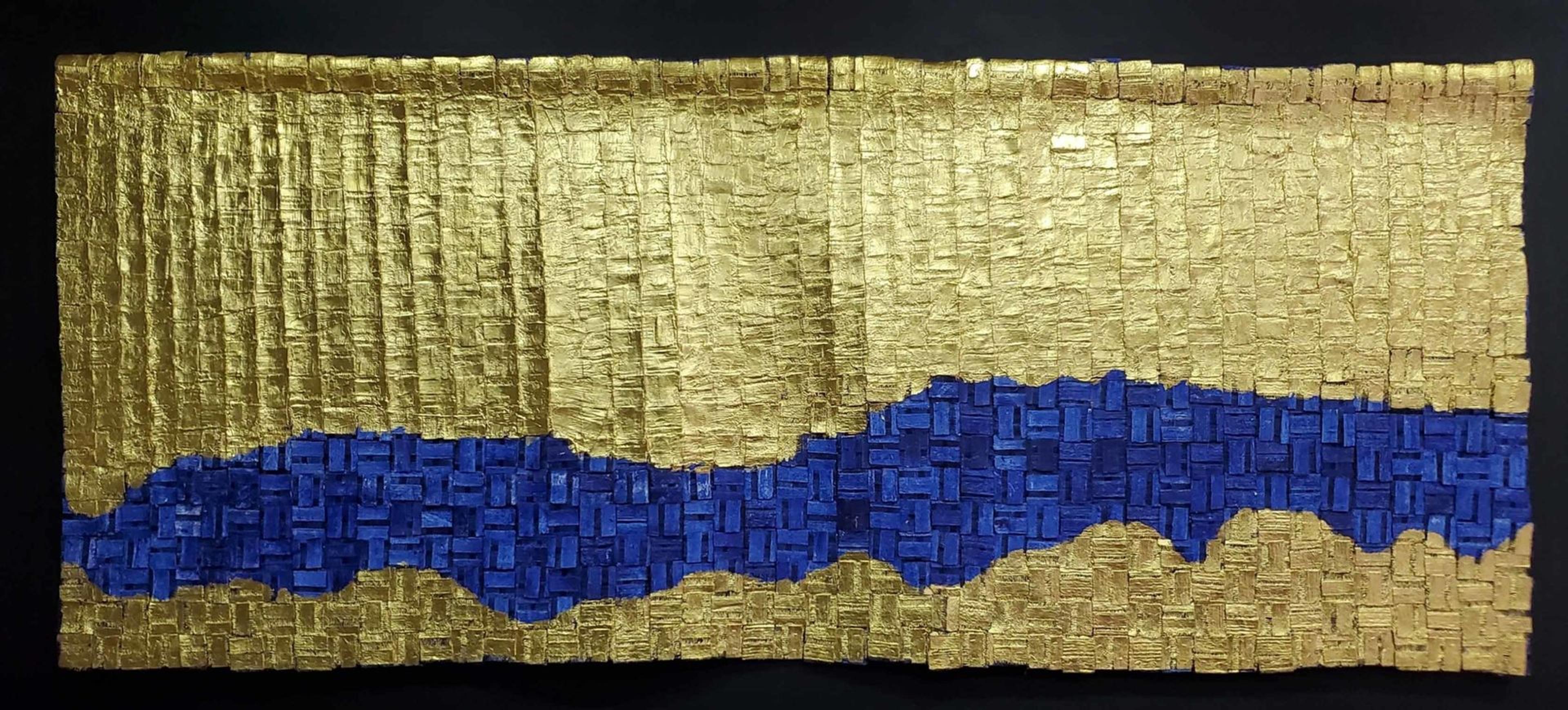

Spanish Colonial influence is common among other modern Colombian artists. Edgar Negret, a sculptor known for crafting geometric suns and flowers in aluminum, attributed one of the conceptual foundations of his work to be religion. He claimed that his native town of Popayán had at least twenty churches. Olga Amaral, an artist known for her gold-leaf tapestries that recall Colombia’s mountains and landscapes, also grew up among Bogotá’s colonial churches. She was fascinated by the mystery of their altars, saints, burning candles, and gold—a material that never oxidizes and that captivated various civilizations across space and time.

Olga de Amaral (Colombian, born 1932). Grieta azul, 2016. Linen, gesso, acrylic and gold leaf, 29 1/2 × 70 9/10 in (75 × 180 cm). Courtesy Banco de la República © Museo Botero - Banco de la República

There’s a myth known as la leyenda de El Dorado, or the Gilded Man. In the sixteenth century, the Spanish crafted this legend around the chief of the Muisca people, who lived in the fertile basins of the eastern Andes mountains, near modern-day Bogotá. It was said that the chief was covered from head to toe in gold dust and conveyed on a raft to the middle of Lake Guatavita, cradled in the zenith of a mountain, where he’d throw gold objects into the water as offerings to the gods. Over time, the legend grew, until eventually El Dorado referred to an entire golden kingdom. In the centuries since the Spanish conquests, many lost their lives attempting to find the hidden empire and its golden treasures.

Figure Pendant, 10th–16th century. Tairona. Gold, 5 3/8 × 6 5/8 × D. 2 in. (13.7 × 16.8 × 5.1 cm). Gift of H. L. Bache Foundation, 1969 (69.7.10)

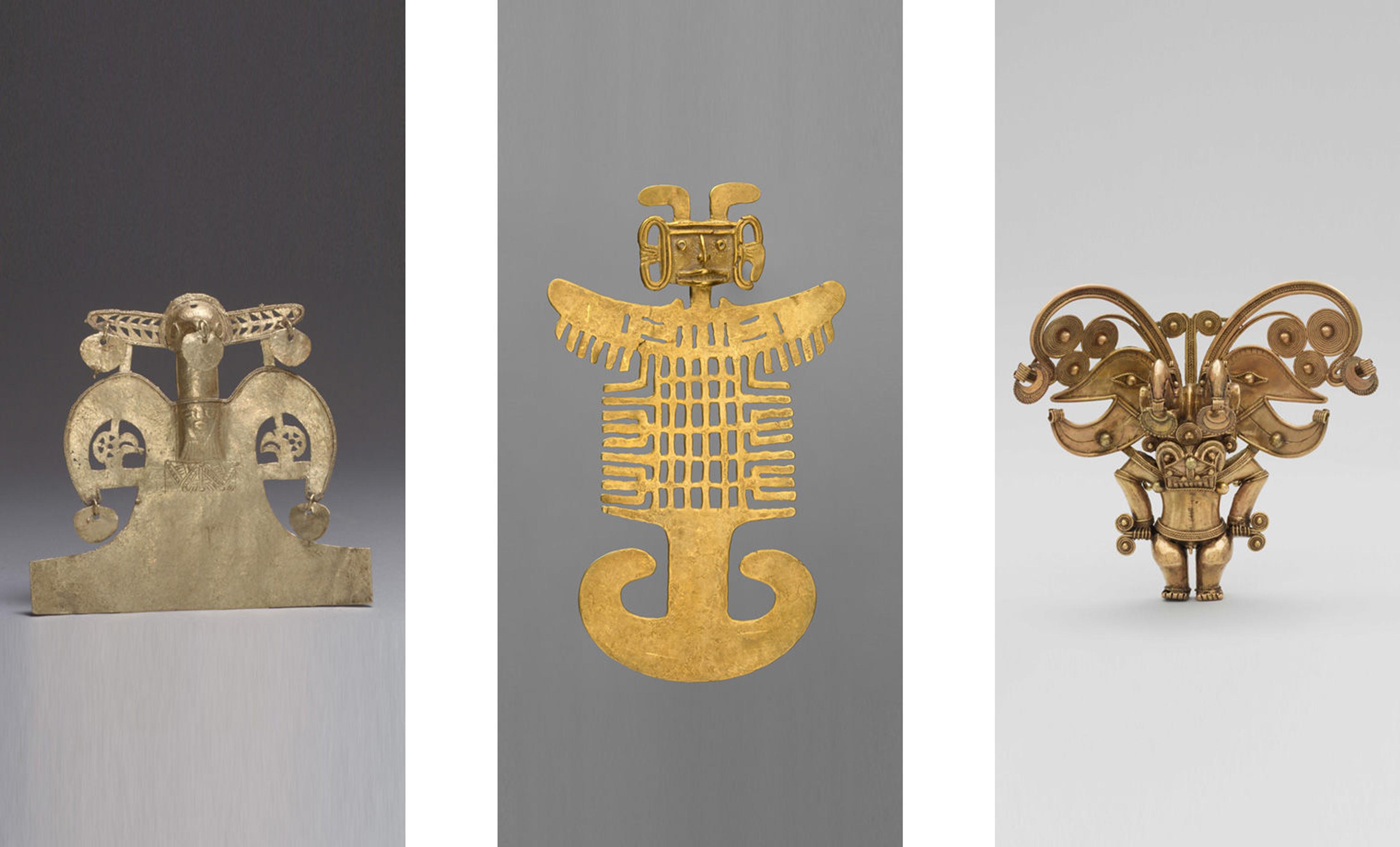

Many Muisca artworks are made of gold and other precious materials. One common Muisca motif takes the form of bird pendants. They’re flat and spread-eagled, with coins hanging loosely from their limbs. Winged creatures were also prominent in the tumbaga pendants crafted by the ancient Tairona people of the Sierra Nevada, a snow-peaked mountain near the Caribbean beach town of Santa Marta. The masked figure above, for example, has human legs, arms, and flexed knees. But it also has a mask flanked by large bird-like wings and the curved beaks of two birds crouched on its head. Its hammer-shaped head and its diamond-shaped snout are similar to those found in certain bats. Tairona believed that bird or bat wings conveyed religious concepts and amplified political power. This cacique, or chiefdom, is believed to depict a shaman in a state of transformation, assuming the features of helpful spirits that would allow him to contact the spirit world.

Left: Bird Pendant, 10th–16th century, Muisca. Colombia. Gold, 4 x 4 3/8 x 3/4 in. (10.2 x 11.1 x 1.9 cm). The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.509) Middle: Costumed Figure Pendant, 1st–7th century, Tolima. Colombia. Gold, 7 × 4 3/8 × 3/8 in. (17.8 × 11.1 × 1 cm). The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.497). Figure Pendant, 10th–16th century, Tairona. Colombia. Gold, 5 1/4 × W. 5 3/4 × D. 2 in. (13.3 × 14.6 × 5.1 cm). Jan Mitchell and Sons Collection, Gift of Jan Mitchell, 1991 (1991.419.31)

Among many ancient American communities, bats and winged creatures were prominent in myths for their capacity to transcend three different worlds: the overworld (supramundo), the middle world (mundo en medio), and the underworld (inframundo). In a conference held by the Gold Museum of Bogotá, former curator Clemencia Plazas described these worlds in detail. The overworld above us is yellow and masculine, associated with warmth, rationality, and transcendence. The underworld, which is blue-violet and feminine, is associated with decay, knowledge, intuition, and pain. It is death, where the sun and seeds die; but it is also regeneration, because the sun always rises, and seeds and flesh nurture the soil back into new life. While bats inhabit the underworld, they can leave their world and physical environment. Their sharp night vision and echolocation allows them to fly up easily into the sky and return back to earth. In that sense, they helped humans transcend worlds.

* * *

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, many artists, scientists, and writers began to explore Latin America. The Prussian explorer Alexander von Humboldt produced composite engravings of different sites and his writings prompted explorers such as the artist Frederic Edwin Church to travel to the Americas as well. The painting Heart of the Andes(1859) was inspired by Church’s travels throughout South America. The Andes are the world’s longest continental mountain range; it slices through Venezuela, Ecuador, and Colombia, extending south into Chile and Argentina. Church’s painting of the Andes specifies no country or unique location. Instead, it portrays an idealized landscape. A cross in the foreground and a white town poised before a lake are the only hints of a place that might very much be real.

Frederic Edwin Church (American, 1826–1900). Heart of the Andes, 1859. Oil on canvas, 66 1/8 x 120 3/16 in. (168 x 302.9cm). Bequest of Margaret E. Dows, 1909 (09.95)

Church documents knotted foliage, dirt-coated walls, and curling thickets. These are the Andes you might see when you travel from one Colombian city to another, speeding down their winding bodies and edging close to vertiginous precipices. In Bogotá, pine and eucalyptus trees sheathe the mountains in an even green that dims to a brooding blue when observed from afar. Near the plateau of Villa de Leyva, some mountains appear like knuckles rising from a strip of desert red. In a sense, seeing Church's depiction of the Andes is reminiscent of reading socio-political news about Colombia in the foreign press. These compelling depictions memorialize one facet of a dynamic landscape. They hold fragments of a story, but not its entirety and rarely its nuances.

Left: Jewelry inspired by Pre-Columbian artifacts discovered by the Cano family in the late 19th Century. Earrings, Andes Collection. Photograph by Andrea Quintero. Images courtesy of Cano Jewelry. Right: Mochila handbags created by Verdi. Image courtesy of Verdi.

Today, many artisans like CANO craft jewelry that references the Pre-Columbian artifacts of our ancestors. Modern design also draws inspiration from our landscapes and traditional craftsmanship. The textile brand Verdi uses traditional coffee-sack weaving techniques and local materials such as Amazonian yaré and plantain to craft furniture, art, and ethnic mochila handbags. Even if we don’t realize it, fragments of our country are continuously revived in our everyday life: Bogotá’s airport, El Dorado, commemorates the myth that brought Spanish conquistadors in search of gold, and Colombia’s most prestigious university is named after the Andes mountains. Art provides a different way of looking at and understanding a country’s past, moving past sensational headlines and reminding us that Colombia's past is rich, varied, and in some instances, beautiful. These traditions are continuously updated for the contemporary world and they remind us that cultural heritage, while grounded in the past, can be very much alive.